C‘est la vie.

Translation: Roland Barthes on Tombley One: The Wisdom of Art

No matter how fickle the painting is, whether it is supported by a board or a wooden frame, we are always faced with the same question: what is happening in the picture? Canvas, paper or walls, can be used as a vehicle for events (even in some art forms, the artist deliberately wants nothing to happen, but it is still a scene of adventure). From this, painting can be seen as a stage play: in which we watch, wait, receive information and understand it; then, the curtain falls, the scene ends, and the painting remains in our memory: but we are no longer The old selves again, because we have been touched by this event. What I want to examine is Tombley's relationship to "events".

The scene presented to us by Tombley (whether on paper or canvas) contains several different types of events that are well differentiated in ancient Greek: what happens is fact (pragma), coincidence ( tyché), result (telos), surprise (apodeston) or action (drama).

I

Originally, pencil, oil paint, paper, canvas, these drawing tools existed as a fact. Tomber treats these materials in his own way, not wanting them to serve a purpose, but as absolute matter, manifesting in the radiance of its existence (the theological term "radiance of God" is refers to the existence of God). These painting tools are like the "raw materials" used by alchemists. These "raw materials" exist before meaning is produced, and the paradox is that in the order that human beings identify with, there is nothing that immediately accompanies meaning. The power of the painter, like the creator, is that he can make the material exist as matter; even if meaning emerges from the canvas, pencil and paint can still be "things", their material properties have not changed, and no meaning in the picture can eliminate them The fact that "exists".

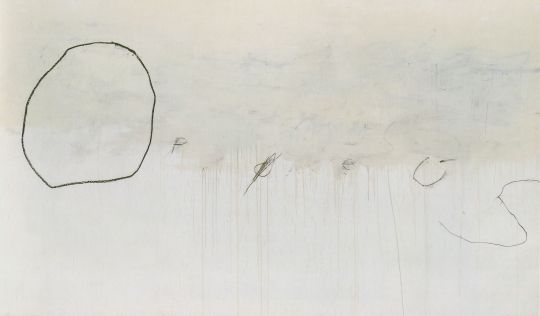

Tombley does not intend to show us his depiction of the picture (this is another question), but his processing and deployment of the painting: a few pencil marks, graph paper, a touch of pink, and a small patch of brown. This kind of art has its secrets. To put it simply, Tombley does not simply spread the materials (charcoal, ink, oil paint) on the picture, but in turn, let the materials affect the whole picture. One might think that in order to make pencils more expressive, they should be pressed very darkly and thickly against the paper. Tombley's idea is just the opposite: he does not compete with the material, but uses loose brushstrokes to let the graininess of the material appear on the picture, so that the material shows its essence, so that we are convinced that it is left by the pencil trace. More philosophically, we can say that the essence of things lies not in their weight, but in their lightness; and thus we might confirm a statement of Nietzsche. "Beautiful things are light": no one is more romantic in this sense than Tombley.

In any case (in all works), let the material appear in the form of a fact (pragma). To do this, Tombley did not use any special technical means (if there were, it was a very fine art), but out of his habit. We don't know if other painters also used this habit, but in any case, this way of scheduling, combining, and distributing materials is unique to Tombley. Everyone masters the use of words, but sentences are the author's original creation: Tombley's "sentences" are imitated by no one.

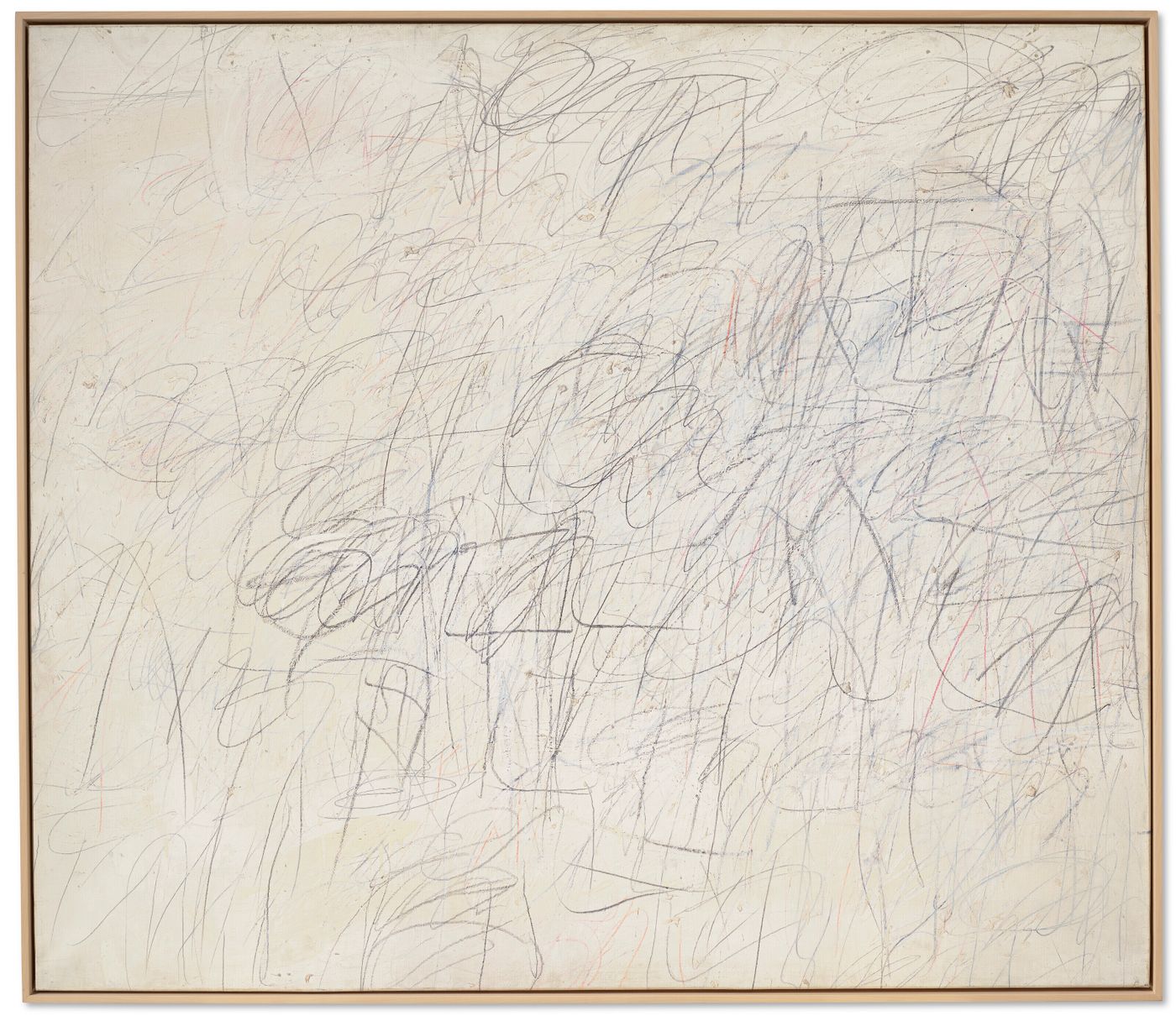

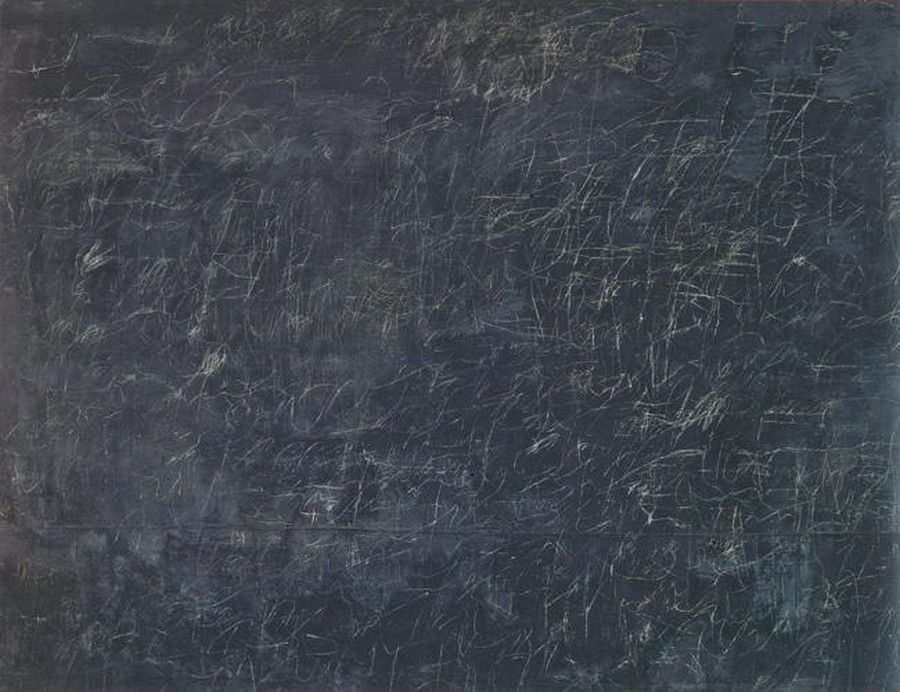

Tombley showed traces of the material in this way (similar to a spell, can we say he used it?). He scribbled lines across the canvas; back and forth, letting the lines "randomly" wander, like a bored person at a meeting aimlessly blacking out a corner of the paper in front of him; Yes, Tombley guides and manipulates these traces as if with his own fingers; his body is always close to the canvas, and the process of painting is like a gentle stroking, rather than standing at a distance and dripping paint on the canvas ; perhaps we should call these marks stripes, because they remind us of textures on animals: the materiality of the texture of paint or pencil is often difficult to define, and Tombley seems to like to layer the lines, as if in constant modification, blurring Their texture, which is not the case, the texture of these lines is still looming under the layers; it's a clever dialectic: the artist pretends to "mess up" part of the picture and wants to erase it. However, he also broke the part he wanted to correct, and the two failures added together to produce a subtle effect, like a kind of oblivion (a parchment manuscript with old words and new words written, but usable A special method to reproduce the original): they bring depth to the canvas, like in the sky, where the light clouds drift in front of each other, but are not connected.

We should note that all of these actions aimed at turning material into fact have to do with leaving a trace or even soiling something. Here comes a paradox: if the truth is unclean, it is more pure. Proof that an object is in everyday use, not in its new, pristine state, but in its used, deformed, slightly stained, or even abandoned state: perhaps the truth of things can be better discerned in the wreckage . The red is in the messy smearing; the truth of the pencil is in the swaying lines. The idea (in Plato's mind) is not a shiny bronze statue in a conceptual frame, but a faint mottled swaying on a blurred background.

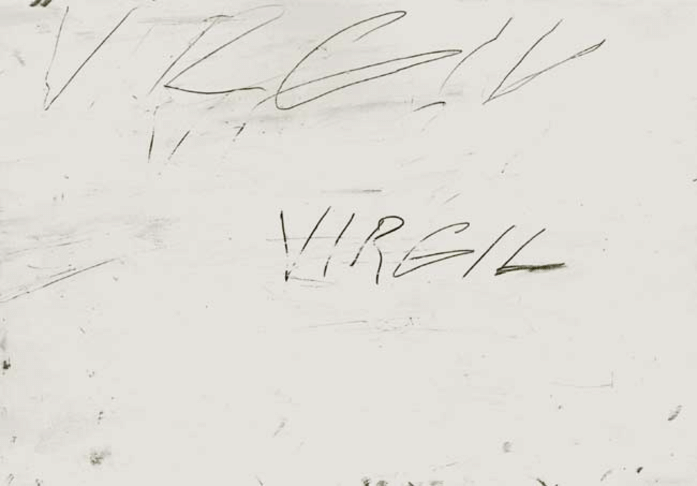

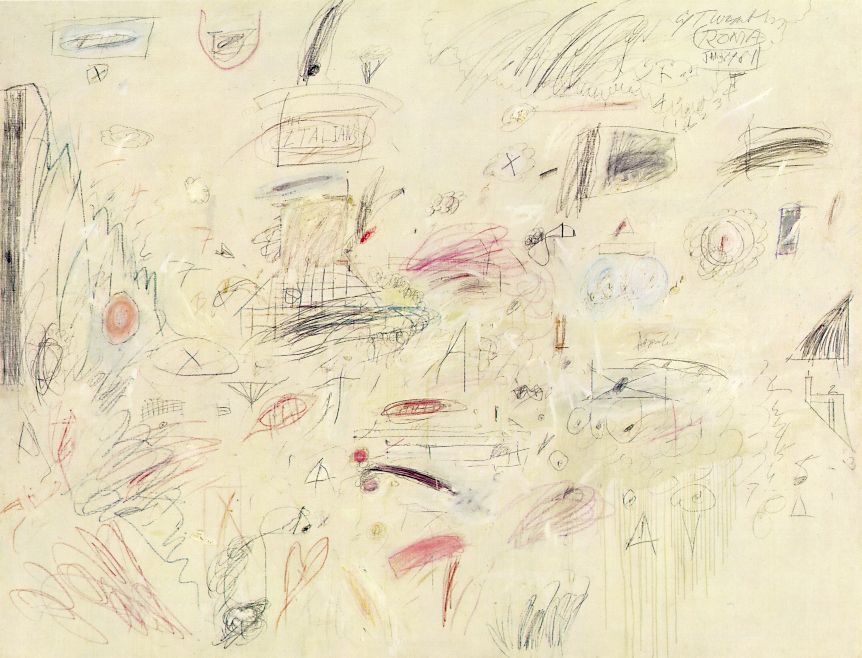

The facts about painting are numerous, and in Tombley's work, writing and names are often present as facts, such as Virgil and Orpheus, who are like characters standing at the center of a stage without sets and props. But they're not nothing but names: the childlike, crooked handwriting shows all the clumsiness of a hand trying to write, a far cry from the typographical fonts commonly used by conceptual artists; perhaps that's why it's better The truth that embodies these names: Don't elementary school students learn things by copying new words over and over again? By writing the name Virgil on canvas, Tombley condenses the vast epic world of Virgil into his own pen, a name that acts like a library of references. That's why we shouldn't try to generalize or make analogies to Tombley's work. If a painting is titled The Italians, apart from that name, we can never really find Italians in the painting. Tombley knew that names had an absolutely powerful evocative power: by writing the word "Italian", all Italians were mentioned and even met. The name is like in "One Thousand and One Nights", I forget which story, the jars are written: the elves are hidden in the jars, if you open or break the jar, the elves will fly out like smoke Generally floating in the air: break the title and the whole picture will run away, elusive.

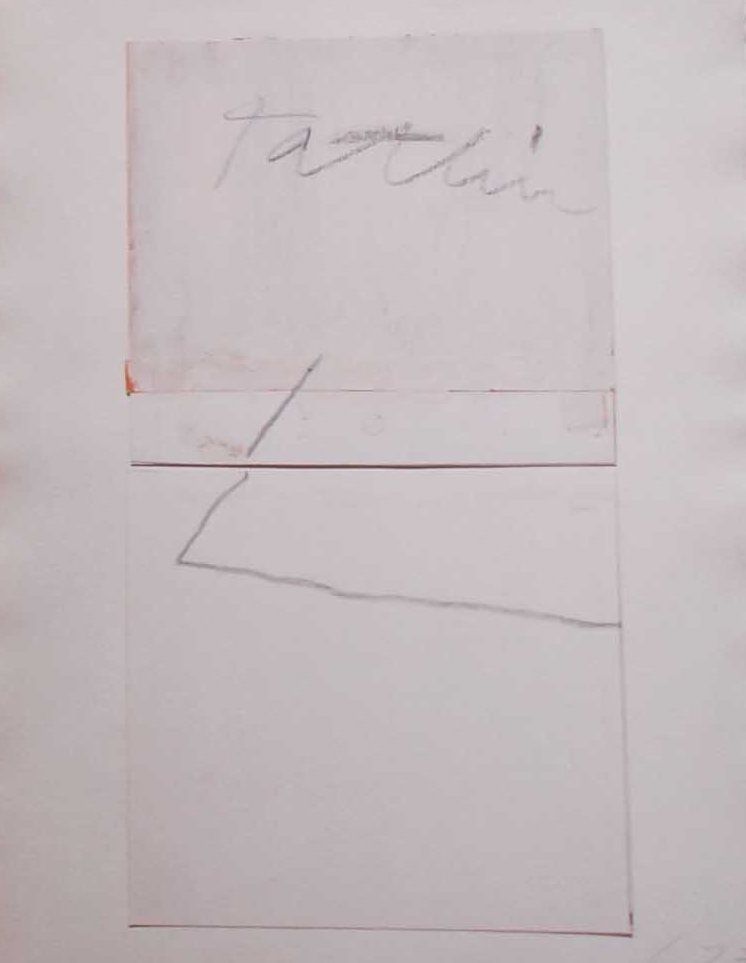

The title of the work is also a pure demonstration of this creative method. For example, several of Tonbury's works: To Valery, To Tatlin. The whole work is just the handwriting of the inscription (to so-and-so). According to the linguist Austin, we can call the act of inscription an act of representation, because their meaning is fused with the act of stating them: "To so-and-so" in addition to effectively expressing what I did The (my work) is for people I love or admire and have no other meaning. That's exactly what Tombley did: just the inscription, the content of the picture is not even there: just the act of "to so-and-so", and the few words necessary to express it. This is the limit of painting, but it is not that nothing is painted on the canvas (some painters have tried this), but because the concept of painting itself is broken, the painter still expresses his feelings with the person he loves.

II

Tyché means a chance coincidence in Greek. There is always a power of chance or coincidence in Tombley's pictures. In fact, it was the result of his careful deliberation. The point is that this effect of coincidence, or to put it in a more subtle way (since Tombley's creative process is not random): inspiration, this creativity is like a coincidence-like pleasure. It can be explained with two actions and one state.

The action, first of all, is "throwing": the paint seems to be thrown lightly onto the canvas, and the act of "throwing" contains both a decisiveness at the head and a hesitation at the end: by "throwing", I recognize the action, but I don't know what the result is. Tombley's "throw" is elegant, soft and long, like a good bowler; however, this leads to fragmentation of the picture; the elements of the picture are scattered on canvas or paper, widely spaced from each other The blank; Tombley often fuses writing and painting, and in this he shares similarities with oriental painting. Even though some parts of the picture are portrayed strongly, Tombley still leaves a lot of airy parts; these spaces are not only for the plasticity of the picture; their appearance is a subtle energy, so that the audience can better Breathing: An illusion like what the philosopher Bachelard called "sublimation": floating in the sky. A state associated with the actions of "throwing" and "spreading" appears in all of Tombley's work, and that is "Rarus": Latin for sparse, gapped, with Porous, dispersed, the word explains well how Tombley deals with spatial relationships.

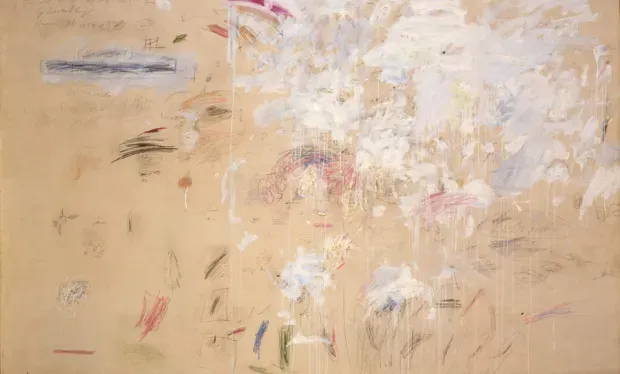

How to connect the concepts of "gap" and coincidence? Valéry (to whom one of Tombley's paintings is dedicated) can help, as he studied the way artists make in two cases in a 1944 course at the Collège de France: the creation of works according to a pre-established plan, Or push and fill a rectangular picture in an imaginative way. Tombley is the latter, he fills a rectangular picture according to the principle of white space. The concept of blank space is crucial in Japanese aesthetics, which is different from Kant's interpretation of time and space, but a more subtle relationship of separation. "Blank" and the Latin "Rarus" have similar semantics, and both can be used to describe Tombley's artistic concept. Therefore, the gap in the picture contains the characteristics of two civilizations: on the one hand, there is the "blank" in oriental art, which is embellished with calligraphy; Surprisingly, Valéry also has his own thoughts on this, he thinks that these blank spaces are different from the vast sky or the sea, but like the traditional buildings in the south of France: "In the noon of these large rooms, it is very suitable for meditation, empty. And there is no large furniture, time seems to stop. Only fill this huge emptiness with spirit." In fact, Tombley's picture is like a large Mediterranean room, warm and bright, filling the blank part with spirit.

III

The composition of Mars and the Artist is highly symbolic: the top half of the painting is a tussle of lines and red, representing the god of war, and the bottom half of the painting features flowers and the word "artist". The combination of figurative shapes and abstract patterns makes the picture look like some kind of pictogram. The framework is so clear (although this is not Tombley's usual approach) that it leads us to confront the common problem between image and meaning.

While abstract painting (we know the name is inaccurate) has been around for a long time in the history of painting, every artist since Cézanne has struggled with the same problem: in art, the problem of language has always been Not really solved: the problem always takes us back to the language itself. Therefore, it is by no means a naive act to think about the meaning of a painting (although this act is always reprimanded from the cultural field, especially the professional cultural field). Meaning is always attached to us: even if an artist wants to create a work that is meaningless or beyond meaning, he will eventually create meaning that is meaningless or beyond meaning. Doing so only keeps legitimizing the question of meaning more and more, which creates the universal barrier to painting. When many viewers (due to cultural differences) feel "incomprehensible" about a work, it's because they want meaning from it, but the picture itself doesn't give them any meaning.

Tombley tackles this problem in an understatement: Most of his work has titles, which he uses to bait the audience with meaning and address their hunger for meaning. In classical painting, the title (viewers always turn their attention to the thin line of text at the bottom of the work) often expresses the content of the picture clearly: the title makes the image and meaning in the picture more detailed and thorough. Because of this, when people see the title of Tombley's work, they will immediately have a conditioned reflex to look for an image in the picture that matches the title. Where is the Italian in the title? Where is the Sahara Desert? Of course, we cannot find them in the painting. We can only find the picture itself, the events of which are ambiguous in their mysterious brilliance: no clear image represents the Italians or the Sahara, yet we do not feel that the picture contradicts the title. In other words, the audience will vaguely acquire a logic (and the way of viewing changes accordingly): although the picture is obscure, it still has an outlet, which points to a certain teleological end.

This exit was not found in the first place. In the early stages, the title is a hindrance to entering the picture, with its precision, intelligibility and classicality that is neither kitsch nor surreal, following the path that echoes the picture, but seems to be quickly blocked. Tombley's titles have a labyrinth-like function: after following the ideas they imply, we have to retrace our own path and start in another direction. However, something remains on the screen, infiltrating it like a ghost. They are the negative moments of all enlightenment. This art follows an intelligent and sensitive rare way of constantly experiencing negation in a mystical way, where they have to look at all that is not there, finally perceiving in it an emptiness or a flickering shimmer. What Tombley's paintings produce (their purpose) is very simple: an "effect". The term has to be understood here in a strict academic sense: the high-step school in the history of French literature at the end of the nineteenth century to the stage of symbolism. "Effect" in this sense refers to the general feeling implied in the poem, which is usually presented visually. This is well known. But what is special about the effect is that its overall characteristics cannot really be decomposed, it cannot be reduced to the sum of local details. In a poem by Théophile Gautier called "Symphony in White Major", all the lines are meant to emphasize and convey to us the whiteness, so as to achieve a reference that does not require any object, imprinting the whiteness independently in our minds. Likewise, Valéry wrote two sonnets during his Symbolist period, both titled "Féérie", the effect of which is also a certain color. In the period of high treads to symbolism, we can no longer describe white in general like Gautier, and the feeling (under the influence of the painter) is more refined; it may become some kind of silver-based, mixed with A number of other sensations are added to diversify and intensify the tones: lightness, transparency, lightness, acuity, warmth of color: the paleness of moonlight, the silkiness of feathers, the sparkle of diamonds, the radiance of shells. The effect is not a rhetoric, but a real feeling, defined by this paradox: the indissoluble unity of impressions ("information") and the complexity of causes, elements: universality is not mystical (this It is entirely due to the power of the artist), but it is inescapable. This is another logic, a challenge by poets (and painters) to the structural rules of the Aristotelian school.

Although we can distinguish Tombley from French Symbolism on many levels (art, era, nationality), they still have something in common: some form of cultural connection. This cultural form is classical: Tombley not only made direct reference to the way myths were transmitted in Greek or Latin literature, but also introduced the concept of "author (and guarantor)" in his works, such as the humanist poets (Valery, Keat) Or the ancient painters (Poussin, Raphael). A chain begins to emerge, from the Greek gods to contemporary artists, the chain connecting Ovid and Poussin. Like a golden triangle, it connects sages, poets and painters. One of Tombley's paintings was dedicated to Valéry, and more coincidentally, perhaps unbeknownst to Tombley, another of his paintings had the same title as one of Valéry's poems: "The Birth of Venus." The two works have the same "effect": emerging from the sea. Such coincidences can be used as an example for our understanding of the "Tumbury effect". It seems to me that there is an effect that pervades the word "Mediterranean" in all of Tombley's work, even before he settled in Italy (as Valéry puts it, previous causes lead to future effects). The Mediterranean is a vast complex of memory and perception: the Greek and Latin words that often appear in the titles of Tombley's works, a culture, history, mythology, poetry, all these forms of life, color and light on land and sea occurs at the junction. What is unique about Tombley is that he deliberately enhances the "Mediterranean effect" (scratch, smear, smear, color blocks) in the use of materials that seem to have nothing to do with the great Mediterranean civilization.

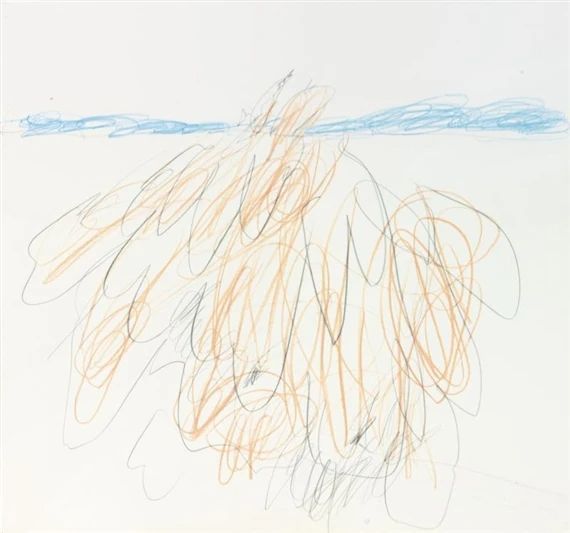

Tombley had lived on the island of Procida in the Gulf of Naples, and I had been there, spending a few days in the old house where Lamartine's heroine Grazirazzi lived. There, light, sky, earth, silhouettes of rocks and arches merge peacefully. This is what Virgil's poem looks like in Tombley's painting: the gap between the sky and the water, and the traces floating in it that indicate the very lightness of the earth: the blue of the sky, the grey of the sea, the pink of dawn.

IV

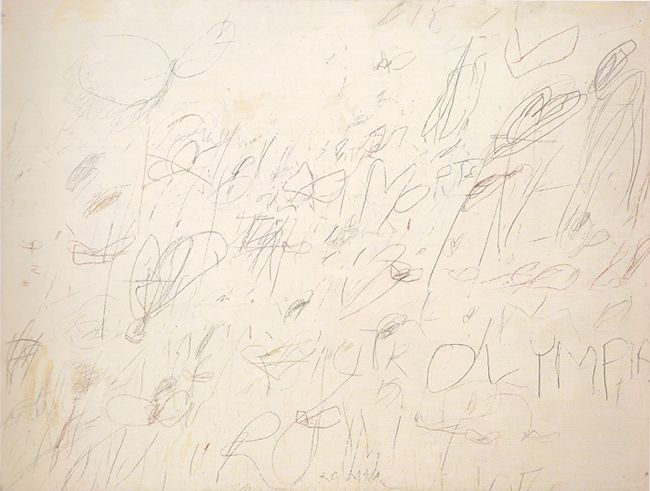

What happened in Tombley's painting? A Mediterranean effect. However, this effect is clearly not "frozen" in the pomp, seriousness, and affectation of humanism (even a well-conceived verse like Valéry's is often imprisoned by a refined decency). Tombley often introduces surprise (apodeston) into events. This amazement comes in the form of daring, mockery that pops the bubble of humanism. In Ode to Psyche, the scale in the corner breaks the solemnity of the title. In Olympia, there are clumsy patterns all over the screen, similar to what a child would create when he wanted to draw a butterfly. What could be farther from the veil of Orpheus than these childish lines of a land surveyor's apprentice, from the point of view of "style", a value that is admired in all the classics? The grey in Untitled (1969) is so pretty! Two thin white lines hang down diagonally (still left blank); this is very Zen; two almost indecipherable numbers wobbly on these thin lines, mixing the sublime of grey with the understatement of the two numbers interconnected.

Unless, it is because of the existence of these surprises, that we cannot find the purest Zen in Tombley's work. In fact, there is a very important experience in the Zen posture that is not obtained through rational means: it is the epiphany. (Because of the Christian tradition) the word is translated in French as "revelation", which is not exact; sometimes slightly better, it is translated as "awakening". For atheists, epiphany can mean a spiritual shock that enables one to transcend all known wisdom and gain access to the truth of Buddhism: a form of detachment and the emptiness of samsara. What is important to us is that epiphanies are achieved through amazing techniques: techniques that are not only irrational, but even somewhat rash, contrary to the seriousness of what we think of religion: they are sometimes an A nonsensical response to a question, or an astonishing act, conflicted with a solemn religious ceremony (a Zen master stopped abruptly in the middle of teaching Zen, took off his shoes and walked out of the house over his head). Seriousness and dogma often cloud our natural conscience, and such rude behavior is a good opportunity to break through dogmatism. Clearly, freed from a religious perspective, Tombley's paintings contain these insolences, surprises, and sporadic epiphanies.

The words appearing in Tombley's pictures should be regarded as a kind of surprise: every time Tombley leaves a handwriting on the screen, it will cause an impact on the naturalness of the painting. We can simply divide these handwriting into three categories. The first are those tick marks and numbers, which create a contradiction between the impracticality of painting and the utility of mathematical calculations. The second is the works with only handwritten words on the screen. In the end there is a sense of clumsiness that is present in all of these handwriting; the handwriting in Tombley's work has nothing to do with ornament and print; they are not intended to be practical; however, they are not really written like a child came out, because the children tried hard to write, pressing hard on the paper, rounding the corners; they wanted to try to be adults; but Tombley didn't; The handwriting seems to flow from the fingertips, but it does not mean that they are boring, but it is a fantasy that disappoints one's expectations of a painter's beautiful handwriting.

This unreproducible "clumsy" handwriting has a certain modeling function in Tombley's work. Here, I do not want to talk about them in too many art criticism terms, I will emphasize their criticality. Through these handwriting tricks, Tombley always introduces a sense of ambivalence into his work: the combination of "clumsy" and "ethereal" produces a special power that breaks with people's perception of antiquity as a classical form of decoration Repository Tendency: The clumsy notes "shudder" (which is exactly an epiphany) of the Greek, sensual, calm classical beauty of the picture. Tombley's creation seems to be a counter-cultural movement, abandoning the ornate discourse and retaining only the aesthetics. It has been said that, unlike Paul Klee's art, Tombley's work does not contain aggression. If we define this aggression in the Western sense as a release from bondage, then it makes sense. There is a sense of tremor in Tombley's art, but not violence, and tremor is often more subversive than violence: this is exactly the way of Eastern wisdom.

V

In Greek, "drama" is etymologically related to the word "to do". So, can the actions and actions performed on the canvas also be called a play? For my part, I read in Tombley's work two actions, or an action that can be divided into two phases.

The first type of action is culturally relevant, and they are always derived from old stories: Dionysian orgy, Birth of Venus, Plato, battles, etc. Tombley does not intend to reproduce these stories; rather, through their names, he conjures them into his paintings. All in all, what Tombley represents is culture itself, or an artist's interaction with ancient (or contemporary) texts through his own mind or hands. When Youngberry "nested" ancient (considered cultural paragons) works into his own paintings, such representations are remarkably precise: titles in corners or indistinguishable figures, more like notes, rather than the content of the work. The "subject" of classical painting is always "what happened" and is legendary (such as the painter David's "Judith Killing Holofernes"); but in Tombley's work, the "subject" is a This idea is the ancient text itself he invokes - the peculiarity of the idea is that it can arouse desire, it is the object of erotic desire, and it is also the object of feeling.

In French, there is a class of semantically ambiguous words, for example: the "subject (sujet)" of a work is sometimes its "object (objet)" (such a sentence is quite playful, an old rhetorical question), and sometimes the stage The characters on the show also appear as implied authors of the show. In Tombley's works, the picture is of course the subject; however, the subject and object in the picture are determined by the creator, so Tombley himself is the real subject. However, the subject's journey doesn't end there: Tombley's art doesn't seem to involve a lot of deep technical knowledge on the surface, and the viewer can also be the subject of the work. "Simple", "sparse", "clumsy", such qualities attract the audience into the work, this is not an aesthetic pastime, the unadorned and clumsy feeling of Tombley's work causes the audience to have an illusion that they can Try to "recreate" in the same way.

It should be clear that, as subjects of viewing, the types of audiences are diverse, and their different subjectivities depend on what inner discourse they hold in front of the object (the subject is constituted by language). Thus, all these subjects can perform different inner activities in front of the same Tombley work (by the way, aesthetics can be regarded as a scientific discipline, which is not the work itself, but the inner activities of the reader or audience , to some extent, a typology of speech). There are many different subjects watching Tombley (and whispering in his head).

The cultural subject knows how Venus was born, who is Poussin or Valéry; this subject is eloquent and rhetorical. Professional subjects know the history of painting well and know Tombley's place in it. The subject of pleasure rejoices in front of the painting, but cannot articulate this joy; the subject is dumb; it can only keep exclaiming, "This is so beautiful!" This is the little torture that language gives us: we can never explain it Why do we think a thing is beautiful; pleasure brings a certain kind of language laziness, if you want to talk about a work, you have to use more roundabout, more rational words, and hope that the reader will experience from such a paraphrase The beauty of the work. There is a fourth subject, and that is memory. In Tombley's work, there are always some brushstrokes that I don't understand, they seem very scribble, even a little rash. In fact, they were already imprinted in my mind without noticing it, and after I left the pavilion, they came up again and again as a memory, and a stubborn one. Everything changed, and I began to recall those brushstrokes with interest. The fact that I am happy to consume lack does not contradict itself, which is exactly the principle of Mallarmé's poems: "A flower .

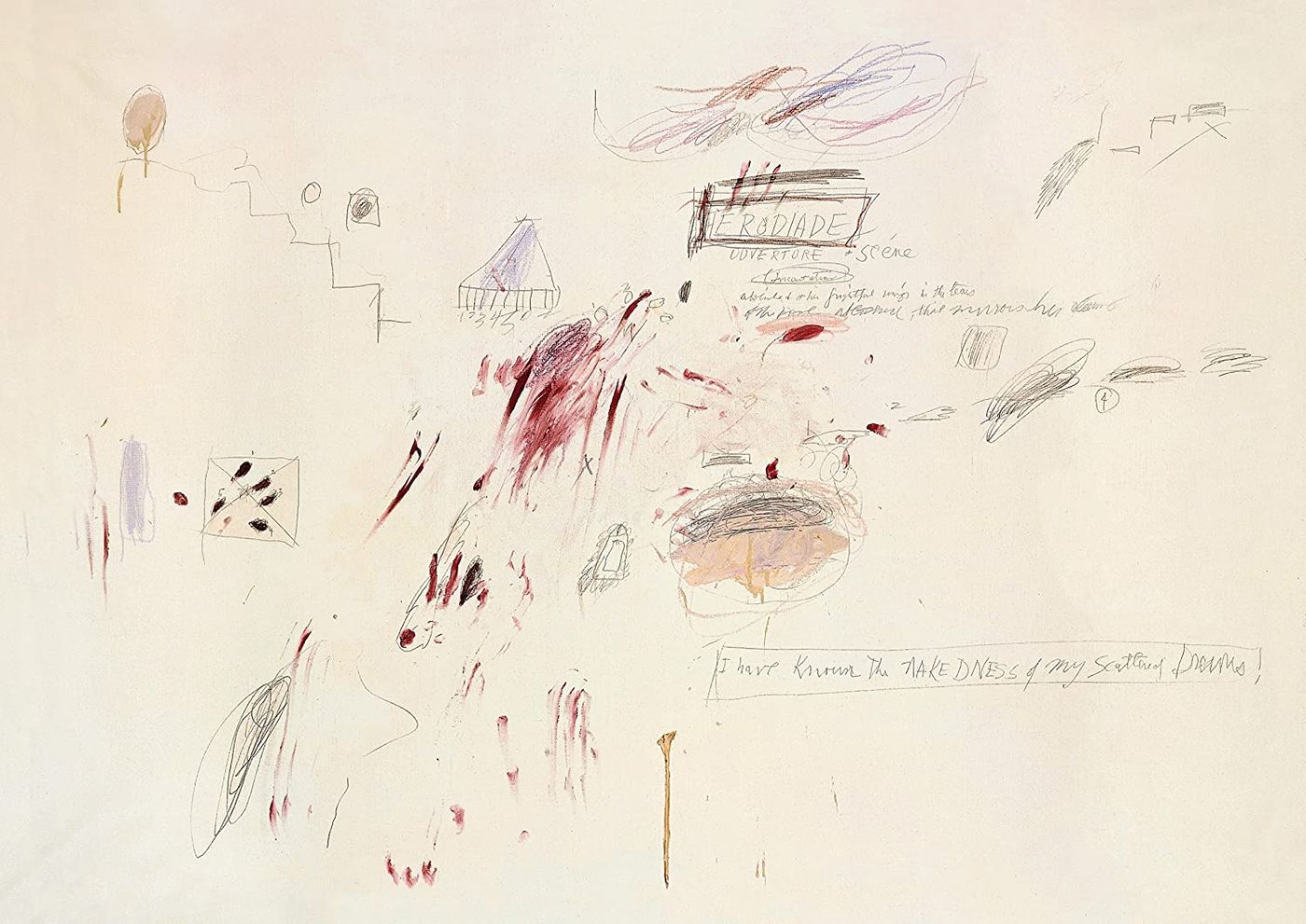

The fifth subject is the producing subject: the subject who wants to re-produce, re-create. On the morning of December 31, 1978, when it was still dark, raining, and everything was silent, I sat down at my desk. I looked at Tombley's "Herodiade" and I liked the painting, but I don't seem to have much to say beyond that. But a new desire suddenly appeared, and I wanted to do what Tombley wanted: to paint at the easel, to play with paint, to leave some traces. In fact, a voice was asking me, "Do you want to be Tombley too?"

As the subject of production, the viewer of the work will discover his own powerlessness - at the same time, highlighting the artist's talent. Before I even started writing, I knew I couldn't draw like that. I will never know why the red lines in the painting "Age of Alexander" can be so light, so that the space of the picture is so flexible. I was always unable to control myself, trying to fill the picture, so that the canvas was ruined; such mistakes made me understand the creative wisdom of Tombley: he should restrain himself and avoid wanting too much; the secret of his success is related to The Taoist concept is not unrelated: the ultimate enjoyment can be achieved through restraint. Likewise, I either draw too lightly or too heavily, and I will never learn to handle pencils as freely as Tombley, because they cannot be reduced to some artistic principle, to keep the free flow of the pencil itself. The Panorama painting is like snowflakes on a malfunctioning TV screen; I don't know how to paint this sense of disorder, and if I'm fully invested in disorder, I'll just mess up the picture. From this, I understand that Tombley needs to pay attention to the disorder and avoid bad lines. This is the fundamental difference between me and the painter. Also, I can't achieve the "thrown", understated feeling that Tombley does: the pictures I paint always seem to have a directionality implicit in them.

Finally, I want to go back to the concept of "white space", which I think is the key to Tombley's art. Generally speaking, "blank" is not very solemn, and even has some kind of provocation, and its alienated density can bring a sense of mystery. Tombley's work produces a new experience: a kind of emptiness, more precisely, the rustling sound of the canvas, however, this instead gives the picture a sense of heaviness; unlike classical painting, the brushstrokes , shape, in short all these events about the image, which in turn confirm that the canvas exists, has meaning, is hedonic (as Taoism says, uselessness is also a form of existence), allowing the four liang to be dialed Move a thousand pounds.

There are paintings that are dominant and arbitrary, imposing their work on others, making the audience worship them in a tyrannical manner. The historical uniqueness of Tombley's art, as well as its moral outlook, is that he does not have a strong desire for control; he wanders between lust and restraint, desire is the motive for his creation, and restraint makes him cautiously away from the desire to control and control the audience. ambition. If we want to expound Tombley's ethical view of painting, we must go outside of painting, outside of the West, outside of history, and go to the boundaries of meaning to find answers. Perhaps as Lao Tzu said:

live without being,

for not relying on,

Long but not slaughtered.

It is for Xuande.

Original: Roland Barthes, « Sagesse de l'art », 1978

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…