副業是在香港中文大學教書,主業是玩貓。

"Hong Kong Lesson 1" 25. Why do Hong Kong people oppose the interpretation of the law by the National People's Congress?

Because program is important. Interpretation by the National People's Congress refers to the final interpretation of the Basic Law by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. The reason why it causes conflicts in Hong Kong, and is even regarded as a challenge to the rule of law in Hong Kong, is that the specific implementation method is obviously different from the understanding of Hong Kong society before 1997, and the scope of application is far wider than imagined. Since the interpretation of the law by the National People's Congress involves the boundaries of Hong Kong's high degree of autonomy, citizens will be very concerned about the conditions for interpretation and the role of the Hong Kong courts in order to meet the expectations of the separation of powers. There may not necessarily be a problem with the interpretation of the law by the National People's Congress, but when it did not happen according to the originally envisaged procedure, it triggered a strong backlash.

Article 158 of the Basic Law defines interpretation as follows:

The power to interpret this Law belongs to the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress.

The Standing Committee of the National People's Congress authorizes the courts of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region to interpret the provisions of this Law concerning the autonomy of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region when trying cases.

The courts of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region may also interpret other provisions of this Law when trying cases. However, if the courts of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region need to interpret the provisions of this Law concerning the affairs administered by the Central People's Government or the relationship between the Central Government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region when trying a case, and the interpretation of the provisions affects the judgment of the case, the judgment of the case cannot be made. Before the final judgment of the appeal, the Court of Final Appeal of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall ask the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress to explain the relevant clauses. If the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress makes an interpretation, the courts of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall refer to the interpretation of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress when citing this provision. However, judgments rendered before that date shall not be affected.

Before interpreting this Law, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress shall consult the Basic Law Committee of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region to which it belongs.

According to the literal understanding, the interpretation of the law should follow the following procedures: First, if the court believes that the incident falls within the scope of Hong Kong's autonomy, it can interpret it by itself. Second, if the court believes that the incident is a matter managed by the Central People's Government or the relationship between the Central Government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the Court of Final Appeal should ask the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress for an explanation. Third, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress should consult the Basic Law Committee before making an interpretation. Fourth, after the interpretation is made, the Hong Kong court must quote it, but the previous judgment will not be affected.

In fact, Hong Kong courts often interpret various provisions of the Basic Law on their own. For example, the Court of Final Appeal ruled in 2013 that the Matrimonial Causes Ordinance and the Marriage Ordinance do not allow women who have undergone gender reassignment surgery to register for marriage with their male partners, which is a violation of Article 37 of the Basic Law "Hong Kong Residents' freedom of marriage and voluntary childbearing rights are protected by law", and then declared that the meaning of "female" in the "Matrimonial Causes Ordinance" must be understood to include the completion of sex reassignment surgery, and medical experts have certified that the gender has changed from male for women.

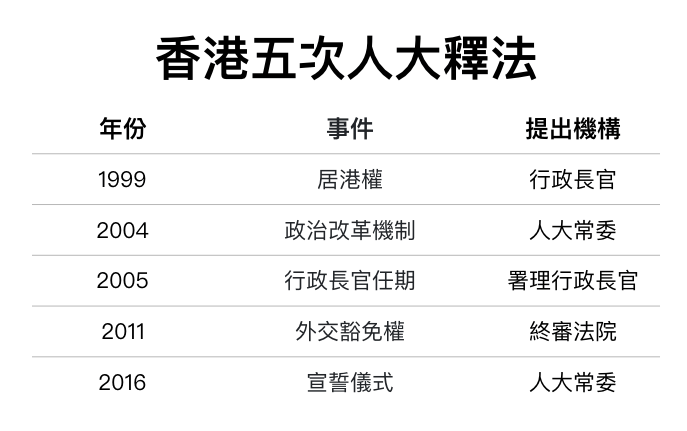

Controversy over the interpretation of the law in Hong Kong is due to the habitual interpretation of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, which bypasses the procedures described in the above-mentioned articles. In fact, four of the five interpretations by the National People's Congress since the establishment of the SAR did not follow the above procedures.

Let’s start with the first interpretation here. In the first week after July 1, 1997, hundreds of people from mainland China went to the immigration department to claim that they were permanent residents of Hong Kong. The source of the matter is Article 24 of the Basic Law, which stipulates that all Hong Kong permanent residents who are Chinese citizens born outside Hong Kong have Chinese nationality children. As a result, many children of Hong Kong people born in mainland China, including many illegitimate children, came to Hong Kong in various ways before the establishment of the SAR, and immediately applied to the government for permanent resident status after the establishment of the SAR.

The Hong Kong government worried at the time that if they were admitted immediately as permanent residents, it would cause a cascade of problems. For example, whether there is a difference between legitimate and illegitimate children, how to prove that the applicant is really a child of a Hong Kong permanent resident (especially if there is only one father, and the mother is his mistress in mainland China instead of his legal wife), and Will similar cases in the future not need to go through the one-way permit system to queue up according to the quota, but can come to Hong Kong directly. Another highly controversial issue is whether this qualification can be passed on from one generation to the next (for example, if a person is born as a mainland Chinese resident, so is his father, but his grandfather has just become a Hong Kong permanent resident, will his descendants will become Hong Kong permanent residents immediately).

In order to deal with these problems, the Provisional Legislative Council enacted emergency legislation within one day on July 9, tightening the entry arrangements for relevant persons, and retroactively going back to July 1 to take effect. This move has caused a lot of controversy. One of the "undocumented children" Ng Ka-ling, represented by her father, sued the amendment as unconstitutional. In January 1999, the Court of Final Appeal made a ruling against Carina Ng, stating that children born to Hong Kong permanent residents, regardless of whether they were legitimate or illegitimate, whether they were adults or not, whether they had a one-way permit or not, and whether they were born in the Mainland or not, have the right of abode in Hong Kong. After all, the provisions of the "Basic Law" do not specify requirements on these aspects, so they should not be restricted.

In response to this ruling, the government estimates that 1.67 million people may immigrate to Hong Kong from mainland China within ten years, which will bring heavy pressure to Hong Kong society. Although this calculation has been accused by many parties as exaggerated and even intended to create panic and affect public opinion, the government still seeks to change the judgment on this basis. In May 1999, the government decided to formally request the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress to interpret the law on the right of abode in Hong Kong, and the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress approved the first interpretation of the Basic Law in June. The content of the explanation states that even children of Chinese nationality born to Hong Kong permanent residents in mainland China must obtain approval from mainland China before entering Hong Kong; and the so-called children of Hong Kong permanent residents born outside Hong Kong refer to Parents have met the requirements for Hong Kong permanent residents.

This interpretation has caused great shock in Hong Kong's judiciary. First of all, this interpretation was not proposed by the Court of Final Appeal, and it was proposed after the Court of Final Appeal had made its final judgment. If so, the Court of Final Appeal was no longer "final adjudication", because its final judgment could have been overturned by the Chinese government, and Hong Kong's autonomy was greatly curtailed. At that time, the legal profession launched a black-clothed silent march to protest. Later, a declassified article pointed out that the five permanent judges of the Court of Final Appeal had considered collectively resigning in protest.

The subsequent interpretations, except for the fourth interpretation in 2011 in response to foreign affairs, have caused a lot of controversy in Hong Kong. The second law interpretation took place in 2004. Without the request of the Court of Final Appeal or any institution in Hong Kong’s political system, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress took the initiative to interpret Annexes 1 and 2 of the Basic Law for the future of Hong Kong. New restrictions on political reforms (see Question 34). As soon as this example was opened, the power of interpretation of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress has become procedurally possible to happen at any time. The third law interpretation took place in 2005, triggered by the resignation of the first chief executive, Tung Chee-hwa. People from all walks of life were concerned about whether the term of the next chief executive should be the new chief executive or a continuation of the original term. In this regard, Acting Chief Executive Donald Tsang directly sought an interpretation of the law from the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress before the Hong Kong court had the opportunity to resolve the dispute, and the role of the judiciary was once again downplayed.

Coming to the fifth interpretation in 2016, the degree of controversy has surpassed the previous four interpretations. The origin of this interpretation is the political turmoil caused by the Secretary-General of the Legislative Council refusing to administer the oath when a member of the Legislative Council allegedly insulted China when taking the oath (see Question 22). Within a month, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress immediately explained the provisions of the Basic Law concerning the oath of public officials, regulating the form and content of the oath, as well as the consequences of failing to take the oath legally and effectively, refusing to take the oath, or violating the oath in the future. From a procedural point of view, there are at least four problems with this interpretation. First, the interpretation of the law was not proposed by the Court of Final Appeal, and even the Hong Kong government itself did not think it was necessary to interpret the law. It was originally proposed by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. Second, when the law was interpreted this time, the Hong Kong court was dealing with a lawsuit between the government and the Legislative Council on the issue of oaths. Government representatives requested that the chairman of the Legislative Council be prohibited from re-administering oaths for the relevant members. The Standing Committee of the National People's Congress interpreted the law during the deliberation of the case, depriving the court of the opportunity to consider how to interpret the Basic Law according to the original procedure. Regulations become useless. Third, the relevant provisions of the Basic Law do not mention the form of the oath, but the content of the interpretation explains it in detail, forming the objective consequence of interpreting the Basic Law in name and adding amendments to the Basic Law in reality. If this is the case, the original normative provisions on the amendment procedure in the Basic Law will become useless. And when the "Basic Law" can be amended without following the established procedures, the authoritative status of the entire "Basic Law" will also disappear. Fourth, the "Basic Law" is a constitutional document, and its provisions should be implemented in the form of local legislation. For example, the specific regulations on the form of oaths are set out in the "Oaths and Declarations Ordinance". When the National People's Congress clarifies the requirements for the form of oath in detail, it is tantamount to infringing on the local legislative functions of the Legislative Council.

In this interpretation of the law, the spirit of the rule of law is downgraded to just "when those in power solve problems in the form of law", as long as the problems are solved. Therefore, critics in favor of interpretation often base their arguments on the grounds that "it is wrong to insult China, so interpretation is right." However, if the purpose of the rule of law is elevated from "governance by law" to "limitation of power by law", it is more important to discuss whether the purpose is right or wrong, and whether those with power exercise their power in an appropriate manner. This is why many public opinion in Hong Kong think that the rule of law in Hong Kong is seriously threatened because of the previous interpretations of the law, because they understand the rule of law in Hong Kong in terms of "limitation of power by law" (see Question 24).

Looking back at the various cases of the National People's Congress interpreting the law, the understanding of the interpretation of the law in Hong Kong society today is quite different from that before 1997.

First of all, the law interpretation process no longer has to be initiated by the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal when it has a specific case and considers it necessary. The understanding of the law interpretation process before 1997 was that after the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress delegated the power of interpretation to the Hong Kong courts, they would no longer exercise this power (this is also the Chinese government’s own understanding of the authorization). When this understanding is broken, the detailed procedure described in Article 158 becomes redundant. The interpretation of this when the National People’s Congress interpreted the law for the first time was that Article 43 of the Basic Law stipulated that the chief executive should be accountable to the Central People’s Government. , report to the central government". However, under this understanding, the separation of powers in Hong Kong will suffer a serious blow, because in the future, if the executive power is checked and balanced by the judicial power, it can be reported to the State Council for the National People's Congress to interpret the law. In order not to disturb the interpretation of the law by the National People's Congress, the judicial power will become cautious when supervising the executive power, so as to avoid the "trick" of the executive power. If so, there will be an obvious imbalance between the executive power and the judicial power, and power will gradually shift to the executive power.

Second, the topics of law interpretation are no longer limited to the affairs managed by the Central People’s Government or the provisions on the relationship between the central government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Even some provisions that clearly fall within the autonomy of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region can be interpreted according to the wishes of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress at any time. This will lead to the "Basic Law"'s protection of Hong Kong's high degree of autonomy suddenly becoming very nihilistic. After all, no matter how detailed these protections are written, they can be overturned by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress at any time in the name of interpretation. If so, whenever there is a major dispute in Hong Kong, no matter whether it is directly related to the relationship between China and Hong Kong, people will no longer care about the mutual checks and balances between the local administration, legislation and judiciary, and then ask the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress whether the interpretation of the law will make the final conclusion, The local public opinion and political process were subsequently emptied, which also deviated from the original intention of "one country, two systems, Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong".

Regarding the fact that the interpretation clauses in the Basic Law can be arbitrarily quoted by the Chinese government, some people think that this is a mistake in the Sino-British Joint Declaration. The "Sino-British Joint Declaration" contained many basic political systems in Hong Kong, and later became the provisions of the "Basic Law". However, the Sino-British Joint Declaration does not regulate the right to interpret the Basic Law itself. Some public opinion believes that the initial signers did not realize that the Basic Law itself had to face the contradiction between the Chinese legal system and the common law system.

Under the common law, the Hong Kong courts operate independently of the government, and interpret provisions from the legal text (including the disputed provision and its relationship with other provisions). Political considerations should not be taken into account in the process, let alone adding that the text itself does not have or meaning that cannot be included. Under China's legal system, China's "Constitution" clearly stipulates that the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress has the right to interpret all laws, and the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, as a political rather than a judicial body, will consider the original intention of the legislation, consider information other than legal provisions, and can also respond to the law New situations that emerged after enactment added new meaning to the legal provisions.

The dispute over legal interpretation is a dispute over procedure, but behind the procedure is also a dispute over value. The value of the rule of law is not limited to "legality is the rule of law." After all, the racial segregation policy in the United States has always been a legal arrangement. What the rule of law pursues is whether the process of making laws can improve itself and achieve justice. As mentioned above, Hong Kong’s executive and legislative powers have many institutional flaws, and the role of the court as the last gatekeeper in the system is already quite onerous and difficult. When the status of the court is further weakened by the interpretation of the law, society's confidence in the entire political system will be further reduced.

The debate over interpretation has brought about a very worrying trend. It is normal to have different opinions and disputes in society. If Hong Kong has a sufficient democratic system, the direction of society can be determined through universal election of the chief executive. When the Chief Executive was not democratically elected, the public turned to members of the Legislative Council to express their dissatisfaction. When the Legislative Council fails to operate effectively, the public can only request the judiciary to uphold justice through judicial review and other means. When even the judiciary loses its due status, does it mean that there will be no more disputes in society? of course not. On the contrary, when disputes cannot be effectively dealt with within the system, they will seek outlets outside the system, forming social conflicts that are more difficult to resolve. When Gun and Yu controlled the water, Yu focused on blocking and diverting. As a result, blocking brought disaster and dredging brought prosperity. So far, the political system of the SAR has blocked public opinion at every juncture. Social instability has its own reasons.

Extended reading:

Chan JMM, Fu HL, Ghai Y, eds (2000) Hong Kong's Constitutional Debate: Conflict over Interpretation. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Gittings D (2016) Interpretation and Amendment, Introduction to the Hong Kong Basic Law (2nd Edition) . Hong Kong University Press.

Tai BYT (2012) Judiciary, Contemporary Hong Kong Government and Politics (Expanded Edition) . Hong Kong University Press.

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…