副業是在香港中文大學教書,主業是玩貓。

"Hong Kong Lesson 1" 31. Why has the protests in Hong Kong become more violent and radical in recent years?

Strictly speaking, although there have been more and more protests in Hong Kong in recent years, none of them have become violent and radical. A more accurate statement is that some have been regarded as the consensus of Hong Kong protests for decades. For example, the insistence on "peace, rationality and non-violence" (referred to as "He Lifei") is no longer regarded as inevitable. Protests of scale that do not conform to the principle of "harmony, reason and wrong" emerged. In addition, society's understanding of relatively aggressive protest actions is gradually changing. The crux of the question is why the social background in which the principle of "harmony and disapproval" was achieved in the past is gradually being regarded as anachronistic today.

Historically, social protests in Hong Kong have had a very intense history. Before the war, the seamen's strike and the provincial and Hong Kong strikes in the 1920s had threatened the British governance of Hong Kong. After the war, the Double Ten riots in 1956 and the Leftist riots in 1967 caused serious social chaos and civilian casualties. However, after the June 7 riots, violent protests became a social taboo. From the late 1980s to the mid-2010s, in order to avoid being labeled as "messing up Hong Kong", organizers of various protests generally consciously avoided violent clashes, even if there was some disagreement with the police in individual demonstrations Pushing and shoving also happened in a point-and-stop form. In order to win the media's attention, it was necessary to break through the police line of defense.

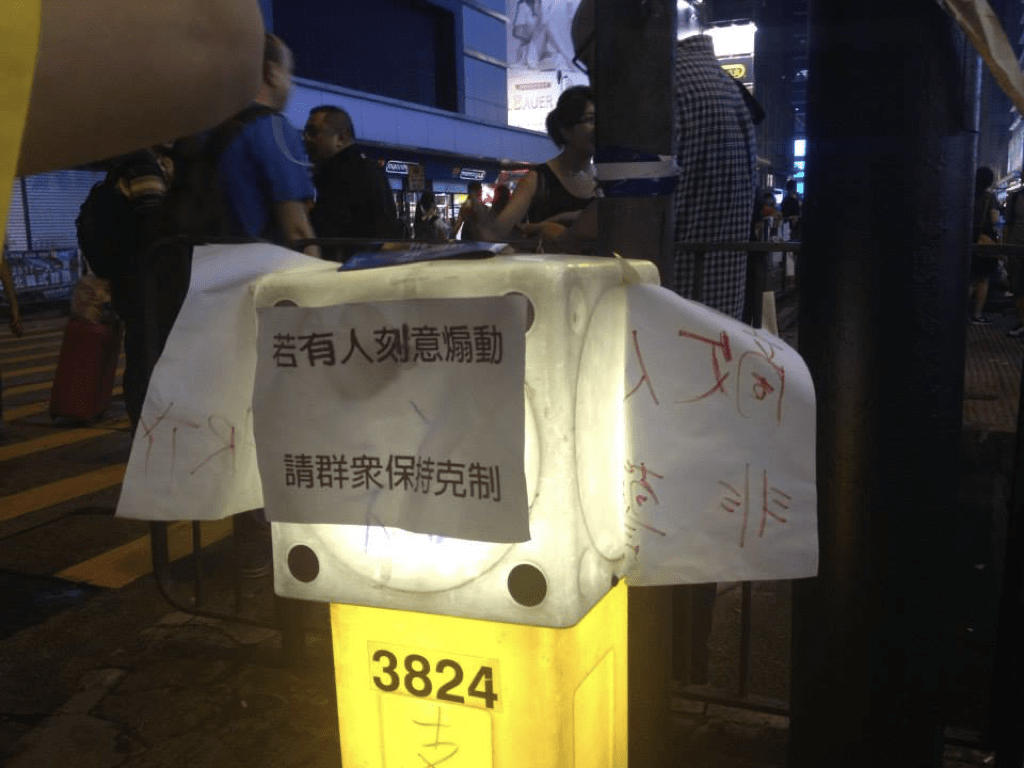

As for some large-scale mass activities, their self-discipline is often used as the basis for moral appeal. For example, after the June 4th party in Victoria Park every year, some participants spontaneously stay behind to help clean up the rubbish. After the July 1st parade in 2003, many commentators praised the participants for their observations, such as "500,000 people took to the streets without overturning a trash can" and "Shops along the way are not worried about business as usual", etc. restraint. By the time of the 2014 Occupy Movement, the most praised aspect of the event was that the participants treated others with courtesy. Citizens in the occupation area set up resource recycling points voluntarily, and university lecturers and middle school teachers set up desks in the occupation area. Students are tutoring for free, and foreign journalists say they have never reported on such a peaceful and large-scale resistance movement that they feel safe.

The organizers' insistence on "He Li Fei" (sometimes plus "non-swearing", i.e. "He Li Fei") is largely due to their belief that the more citizens they can get involved, the more successful they will be. the greater the chance; and to get more people involved, use a method that most people will accept. Looking back on past cases, the number of participants in the 2003 July 1st parade far exceeded expectations, successfully overturning the legislation of Article 23 of the Basic Law. Throughout the world, organizers will also cite cases such as the black affirmative movement in the United States in the 1960s to support the insistence on nonviolent struggle. In addition, the 1989 pro-democracy movement ended with a violent suppression, which also convinced many organizers to avoid bloodshed by insisting on non-violence and not allow the government to intervene by force.

There are also some organizers who are not willing to take the initiative to avoid any conflict. For example, the preservation of the old Central Star Ferry Pier and Queen's Ferry Pier in 2006-2007 blocked the demolition work by means of direct action. In the Star Ferry incident, the actors directly broke into the site to prevent the construction vehicles from running; in the Queen's Ferry incident, the actors slept in the rough for more than half a year, preventing the government from starting the demolition work. Strictly speaking, however, the direct actions they took were limited to the occupation of the site, and they did not attack anyone, which was not considered a violent protest. However, their behavior was still questioned a lot in the social environment at that time, and the discussion about their method of resistance even overshadowed the purpose itself.

The social situation has changed rapidly, and more violent protests than the Queen of Stars have emerged one after another. The organizers who were considered too advanced in the past were criticized for not being radical enough in the new situation. In recent years, the protests have been clearly considered to be radical and even violent, including the many liberation actions since 2012, and the riots in Mong Kok during the Lunar New Year in 2016.

Since 2012, numerous liberation operations have occurred in places where there are many conflicts between mainland Chinese tourists and parallel traders and local residents, including Shatin, Sheung Shui, Tuen Mun and Yuen Long. The organizers believe that the excessive number of tourists and parallel importers from mainland China has seriously threatened the daily life of local residents, so they must "recover" these places from foreign influences. Specific protest behaviors include blocking shops that specialize in mainland Chinese tourists and parallel importers, tracking individuals they suspect are mainland Chinese tourists or parallel importers, and insulting them or even destroying their belongings, such as kicking over their suitcases. These personal attacks were rarely seen in Hong Kong's protests in the past, and were widely discussed and criticized in the mainstream media.

When it comes to the social upheaval caused by the fierce conflict, the most representative one is the riots in Mong Kok during the Lunar New Year in 2016. Unlicensed cooked food hawkers set up on the streets during the Lunar New Year, which is a cultural tradition of the common people in Hong Kong. However, in recent years, the government's law enforcement has become stricter, which is often understood as cultural suppression under the local trend of thought. On the first night of the Lunar New Year in 2016, clashes between government administrators and organisations supporting hawkers turned into a scene of riots rare in recent years. During this period, some people threw debris at the police, and some police officers shot to the sky to warn the sky; some people lifted roadblocks and pushed debris to set fire. The chaos continued until the next morning. The incident sparked a public outcry, both criticizing the participants' use of violence and condemning the police's handling. Afterwards, the police conducted a large-scale search for those involved, and many participants were convicted of rioting.

The Restoration Movement and the Mong Kok riots are anomalies among the many protests in Hong Kong, and most of them still insist on a "harmonious and unreasonable" approach. However, from a discourse level, the understanding of fighting actions in society has indeed changed in recent years. "Harmony and reason" is no longer the bottom line that most organizers insist on, and it has even become ridiculed by a new group of organizers. The popularity of the term "courageous and martial arts" has made relatively fierce methods of resistance more and more acceptable, especially by young people.

For these changes, the traditional political representatives in the non-establishment camp initially chose to draw a clear line, which is the so-called "separation of seats", triggering further splits in the non-establishment camp. Under the electoral system of proportional representation, there are differences of opinion among citizens on whether the protest activities should be radicalized. The different attitudes of politicians is a sign of the fragmentation of the Legislative Council itself (see Question 22). However, there are also individual politicians and commentators who, while disagreeing with the methods of fierce resistance, expressed understanding that some people would choose these methods, and were willing to support them in the face of judicial consequences. It is conceivable that this position is not easy to grasp, and it may even become not a person inside or outside from time to time.

In general, the emergence of radical protests has many similarities to the parliamentary radicalization mentioned above. In parliament, as the opposition political groups remain in opposition for so long, it has become increasingly difficult to persuade supporters that careful compromise can bring about change, and the incentives for unity between political groups have continued to decline. Outside of parliament, the same process is taking place between protest groups. Participants, knowingly or not, no longer believe that cooperation can grow. I didn’t feel the need to coordinate with the organizers in the past, and even believed that their past consensus was the reason for their failure to succeed, so I urged to “dismantle the big stage” and demand the full decentralization of the protest movement. In other words, to understand the emergence of radical protests, it is not only about the actors themselves, but also how they understand the context of their time.

When it comes to the background of the times when "harmoniousness" was challenged, scholar Shen Xuhui discussed it in an article as early as 2011. At that time, he responded to the then Chief Secretary for Administration, Tang Ying-nian, who criticized the radicalization of young people, and believed that it should be understood that Hong Kong's emphasis on "peace and rationality" in the past was not "innate" but had its own unique background. He mentioned that after the June 7 riots, MacLehose implemented a welfare society, which laid the foundation for Hong Kong people to trust in gradual reform; the rapid social development and the government's respect for professionalism also made Hong Kong people believe in the system and are willing to seek changes within the system. Conversely, when society prefers to fight fiercely outside the system, it actually means that the channel within the original system has been blocked.

At the time of Shen Wen's publication, the criticism of "He Lifei" had not yet taken shape, and some protesters' disappointment with "He Lifei" did not become common until other incidents occurred in the future. Among them, the Occupy Movement in 2014 may have played a key role in this. The Occupy Movement originated from the "Occupy Central with Love and Peace" initiative. The original organizers emphasized the peaceful way to inspire more people to participate and prevent others from mixing in and destroying. When the Occupy Movement broke out in full force, the participants were still proud of their "reconciliation" protests, but later the conflict with the police became fierce, and the abuse of power by the police aroused public outrage (for example, "Seven Police Cases", see Question 3 10), and the 79-day occupation movement failed to force the central government to withdraw the "831 Decision" that set limits on universal suffrage.

Since then, society's understanding of what constitutes violent protest has gradually changed. Bringing offensive weapons to attack others is of course violence, but how should you understand when you bring protective equipment to defend yourself against being chased by the police? If an event was not planned or intended to cause chaos, but the police or security response caused chaos or even injured people, would the actors themselves be held responsible? Is it acceptable if the activists only target the abusive police force and voluntarily appeal to other citizens to leave before taking action? When police brutality becomes more and more rampant, many activists believe that some protection is an inevitable choice. In addition, the heavy price of the fierce struggle itself, whether it is physical damage or years of imprisonment, has also become another spiritual inspiration for the struggle. Over the past few years, various subtle but important differences in each conflict have sparked a lot of social discussion about what violence is. On the one hand, activists who support radical methods have an opportunity to reflect on their methods, and on the other hand, society as a whole accepts radical resistance. The degree also gradually changed.

What are the consequences of these changes? The first possibility is that the supporters of "He Lifei" and "Yong Wu" do not trust each other and think that the other party is holding them back. Those who call for shock will be accused by the moderate side of being a lurker ordered by Beijing and will deliberately break up the movement; those who sing and cheer at the rally will be accused by the radical side of engaging in a "karaoke movement", turning the protest scene into a carnival. The contradictions caused by these mutual attacks are one of the main reasons why Hong Kong's civil society has fallen into a low ebb after the Occupy Movement.

The second possibility is that the two sides gradually understand that each has its own role in the movement. Under the premise of "two-way non-separation from each other", "each has his own way", and even achieves a certain degree of mutual complementation. This tacit understanding was evident in the protest over the amendment of the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance, whether choosing to hold an umbrella in front of the police to keep out the pepper liquid, or singing poetry all night to lighten the atmosphere, was accepted as part of the movement. Some commented that after several years of Shen Dian after the Occupy Movement, civil society has a more mature attitude towards the issue of effectiveness. And because the severity of police brutality is far out of proportion, "He Lifei" and "Yong Wu" have the conditions to stand on the same front to condemn.

In general, the emergence of radical and even violent protests is a sign of social imbalance, and just as condemning a patient with a fever will not help him recover faster, the question is why Hong Kong has experienced a series of governance failures. As mentioned above, the Chief Executive's recognition of governance is inherently flawed. However, the measures originally used to remedy such issues, such as governance alliances and political appointment of officials, have not been used effectively, which in turn has further lowered the government's governance prestige. In the past, the government would increase governance recognition by recruiting experts and scholars, but in the era of loyalty first, more and more professionals are pushed out of the system. When the executive power fails, normally the public can supervise through the legislative power. However, as mentioned above, the legislative power has also been obviously dismembered gradually, and both real power and prestige have been lost step by step. When it comes to judicial power, the neutrality and professionalism of both law enforcement agencies and prosecutors are increasingly being questioned, and the adjudicative status of the courts themselves has been weakened by speculation about interpretation of the law. From inside the system to outside the system, the capacity of the mainstream media and traditional civil society groups is constantly being suppressed. Many of the above mechanisms are originally ways to absorb social pressure and turn it into a driving force for reform. When these mechanisms fail one by one, it does not mean that the social disgust behind them will disappear. On the contrary, because social disgust cannot be transformed into a socially beneficial reform impetus, it often has to appear in a more drastic way. To put it bluntly, the emergence of fierce resistance is largely forced by the current situation.

Finally, it should be noted that the movement towards radical violence is not limited to protests. The establishment camp has also learned to mobilize so-called mass movements to support itself, and even does not mind using violent words or even actions to attack others. For example, in early 2017, Law Guancong, then a member of the Legislative Council, was pushed and attacked at the Hong Kong airport by a number of people who claimed to be pro-China, causing him to be injured in many places. All kinds of "patriotic groups" that are more radical than the traditional establishment camp have emerged one after another. The purpose is not necessarily to persuade others to join their camp, as long as the public is tired of all political participation, it is enough to achieve the purpose of maintaining the status quo. Having said that, it is not difficult to doubt that although the establishment camp claims to be opposed to the fierce resistance method, it may actually be happy to see this trend in society. After all, when the method of resistance becomes fierce, the method of suppression can also be rougher, increasing the cost of participation by the general public.

Further reading:

Lin Yiting (2015): "Mongkok Teenagers, Ununderstood Battles", "Tian Media", September 26, 2015, https://theinitium.com/article/20150921-hongkong-occupycentraloneyear02/ .

Shen Xuhui (2011): "How does August Fei Shuang recreate the soil of peace and rationality? ”, Ming Pao, September 5, 2011.

Garrett D and Ho WC (2014) Hong Kong at the Brink: Emerging Forms of Political Participation in the New Social Movement, in Cheng JYS (ed) New Trends of Political Participation in Hong Kong. p347-384

Online resources:

Stand Report (2019) Admiralty's Offensive and Defensive Umbrella Mask Anti-rubber Tear Gas Grenade, June 12, 2019, http://thestand.news/politics/6-12-occupation-Photo Series 2-Admiralty's Offensive and Defensive Battle-Umbrella Masks Anti-rubber tear gas / .

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…