副業是在香港中文大學教書,主業是玩貓。

"Hong Kong Lesson 1" 30. Why has the Hong Kong police been repeatedly criticized in recent years?

This is because many citizens believe that the police abuse their power, enforce the law unfairly, and are selective. If the process of law enforcement by the police itself does not abide by the law, or if there are double standards for the rigor of law enforcement and the failure to treat them equally, it will affect the status of the police in the minds of the public. When the police enforce the law, such as apprehending suspects or managing marches and assemblies, the public begins to question them not necessarily out of professional judgment but of political stance. When the credibility of the police is declining, it will also have a very bad impact on government governance.

The public image of the Hong Kong police has experienced many ups and downs. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, before the establishment of the Independent Commission Against Corruption, corruption in Hong Kong was very serious, especially in the police force. Several important corruption cases at the time, such as the Goldberg case and the Four Inspectors, involved high-level police officers. The reputation of the police force and other disciplined services has been improving day by day as the British government in Hong Kong cracked down on corruption. Police-type themes are common in Hong Kong-produced films and TV series, whether it is action films or comedies, they are deeply loved by audiences.

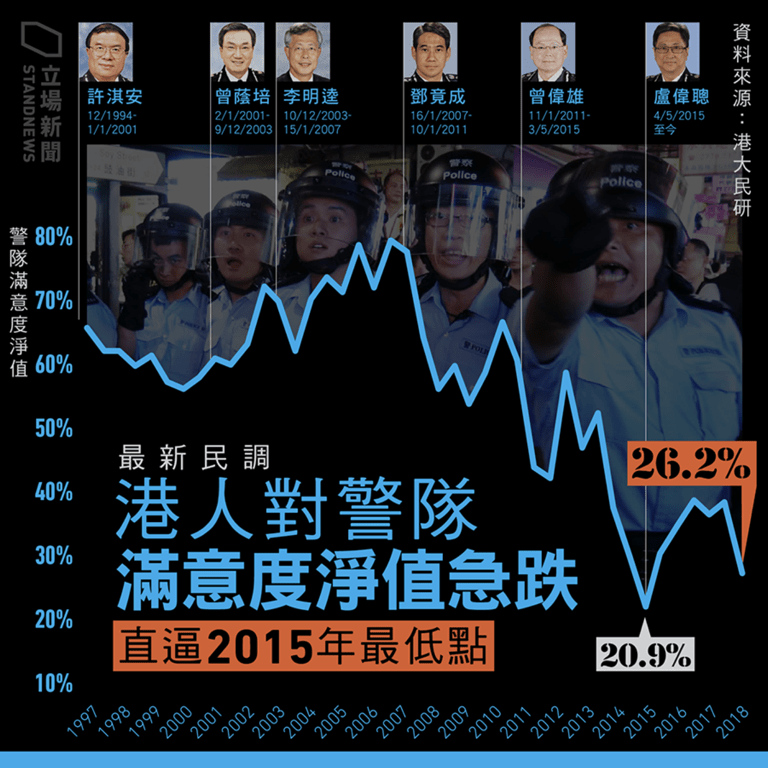

However, the image of the police has taken a turn for the worse in recent years. So far, many citizens have been accustomed to gloat over police scandals and regard the police as the butt of public laughter. The Public Opinion Research Project of the University of Hong Kong has been tracking Hong Kong people's satisfaction with the Police Force since the establishment of the SAR. The Police Force has performed well in the past, with an average of positive 63.1% in the first 10 years of net satisfaction. However, the data has been going all the way down since 2014, falling even more sharply in 2014, and once fell to the lowest point of only positive 20.9% in early 2015.

The freezing of three feet is not a day's cold. It has been a long time since public opinion criticized the police's work from maintaining law and order to maintaining political stability. In recent years, the police have become more and more strict in the management of demonstrations and assemblies, and they have even been criticized for trampling on human rights. For example, during a visit to Hong Kong by then-Vice Premier Li Keqiang in 2011, a citizen wearing a shirt with the words "Rehabilitate June 4th" came to watch the neighborhood where he was visiting, and was immediately forced by a number of officers who did not show their police appointment card. escort away. A reporter stepped forward to shoot, but the camera was blocked. The police later claimed that the citizen had entered the "core security zone", but was strongly criticized by the Bar Association that Hong Kong law has no such concept at all. Even if there is a need for security, a restricted zone should be set up according to the law. the basis of freedom of interview.

Respect for human rights has always been one of the main expectations of Hong Kong society for police professional conduct. The phrase "you have the right to remain silent" when the police arrest a suspect in the film is not just a line of dialogue, but a statement that the police themselves must obey the law and their powers are limited. However, the problem of police's own non-compliance with the law has become increasingly serious. During the 2014 Occupy Movement, the performance of the police seriously deviates from public expectations, completely changing the public image of the police.

In the early morning of September 29, which was the first night of the Occupy Movement, citizens spontaneously occupied the streets of Mong Kok without an agreement. Unprepared for this, the police evacuated the few police officers on the front lines and left an unguarded police car. Seeing that the police car was not overturned or destroyed, the occupiers surrounded the police car with ropes, and rudely used pen and paper to leave a message to persuade other participants not to touch the police car to show the civilized progress of the movement. , it can be seen that they did not regard the police as the enemy at that time, and believed that the police were only assigned to work and were caught between the government and the citizens.

On October 3, a large number of self-proclaimed opponents of the occupation went to Mong Kok to surround and attack the occupiers. Some supporters were beaten to death. However, the police did not strictly enforce the law and even escorted the troublemakers away. Some protesters armed with fruit knives cut down the tents on site. When they were followed up by the media, they claimed, "I carry this knife with me all over the world. I like to eat fruit very much, and I eat it in every country." Destruction and possession of offensive weapons in public places. Since that day, various questions about unfair law enforcement have greatly damaged the confidence of the public in the professionalism and impartiality of the police.

The occupiers thought the police would protect them, followed by trust in the rule of law and human rights in Hong Kong. The Basic Law stipulates that all Hong Kong residents are equal. It does not say that only those who support the government will be protected, and those who oppose the government will not be protected. Based on respect for the rule of law, even murderers have human rights in Hong Kong. The court can sentence a prisoner to jail, but he should still be taken care of his health and diet while in jail, and he should not be beaten at will. To give another example, if a diner smokes in a restaurant, although it violates the "Smoking (Public Health) Ordinance", it is not equivalent to other diners who can slash him with knives, and the police at the scene can't just because the diners "violate the law first". Just stand by. By the same logic, although the occupiers in Mong Kok are participating in actions against the government, at the same time they believe that the police should protect them when they are attacked.

The next "Seven Police Cases" pushed the public's anger towards the police to another peak. On October 15th, seven police officers carried an occupier to a dark corner in Admiralty, kicking and kicking, just as the TV news coverage happened. At that time, the occupiers had their hands tied behind their backs and were incapable of attacking. Many obvious wounds were later found in the hospital during examination. Although the seven police officers involved in the case were suspended, they were not charged until a year later. Although the seven police officers were finally convicted more than two years later, after the sentence was pronounced, supportive police groups and multiple police associations organized rallies to support the seven police officers. None of these gatherings have applied for a "Notice of No Objection" for public gatherings in accordance with the Public Order Ordinance, but the police have not taken any action. Compared with the police's strict restrictions on other demonstrations, this double standard further raises public doubts about the police covering each other up.

Compared to other social controversies, police brutality is the least justifiable. The power of the police is endowed by the people, so it is bound to be limited. The only situation where police use violence must be to protect other citizens, and therefore the appropriate force is used to subdue the person who uses it. In other words, when the other party is incapable of attacking, the police force must stop immediately, because from that moment he has no possibility of attacking other people. If force continues, it is police brutality and abuse of lynching. As for what the other party has done before, whether he has destroyed public property or insulted the police, it has nothing to do with judging the police brutality itself. This is very different from the usual understanding of social disputes where you have to analyze the cause and effect first. There is no need for this when judging police brutality. It can be concluded when you see a policeman attacking anyone who is unable to fight back.

Unfortunately, because police brutality in the Occupy movement has not been taken seriously by the government, more general abuse of power seems to have become part of the police culture. Police brutality was more prevalent in the conflict sparked by the extradition bill than it was during the Occupy movement. During the clearing operation on June 12, the police kept spraying pepper liquid to disperse passers-by who were resting and indicated that they were incapacitated; some demonstrators who had fallen to the ground were surrounded and beaten by several police officers; the police fired beanbag rounds at the demonstrators When shooting rubber bullets, they did not shoot at each other's lower body as directed, and there were many cases of being shot in the face; a number of journalists were shot, beaten, or sprayed even when they identified themselves and did not obstruct police operations. Pepper liquid. All these things are far from the professional image that the Hong Kong police were proud of in the past. The general public questioned that because the police had become a tool of political repression, the government no longer monitored police brutality and abuse of power.

The doubts that politics has overshadowed the rule of law are not limited to the police themselves, but also include dissatisfaction with the government's public prosecution system. Article 63 of the Basic Law stipulates that "The Department of Justice of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall be in charge of criminal prosecution work without any interference." However, many public opinion views this provision as mere fiction. Related to the demonstrations and rallies in recent years, there are doubts about the excessive arrests by the police and the excessive prosecution by the Department of Justice. In recent years, the number of people arrested and charged for demonstrations and rallies has increased significantly. However, many of them were eventually withdrawn from their charges or acquitted by the courts. The government was accused of abusing the judicial process to intimidate demonstrators.

Questions about the failure to achieve fairness and impartiality in the prosecution work have arisen many times since the establishment of the SAR. Among them, the Hu Xian case in 1998 was the first case. The case was originally when a newspaper under the Sing Tao Group was revealed to have exaggerated its circulation and defrauded advertisers. The chairman of the group, Hu Xian, was accused of conspiracy, but was exempted from prosecution by the then Department of Justice. The reason was that he did not want to see the group cross Taiwan and was worried about "leading to wider layoffs." Such a statement is tantamount to claiming that people with economic influence in Hong Kong are different from ordinary citizens and enjoy a special status in the face of criminal prosecution. "Equality in front of you" caused a public outcry.

In the early years of the SAR, the case of Zhang Ziqiang also caused controversy over the prosecution decision. Zhang Ziqiang kidnapped Li Zeju, the eldest son of Hong Kong's richest man Li Ka-shing, and the second richest man, Guo Bingxiang, around 1997. He was later arrested in mainland China and charged with illegal trafficking in explosives and kidnapping. At the time, he argued that he was a Hong Kong resident and the crime took place in Hong Kong, and sought the help of the Hong Kong government for extradition to return to Hong Kong for trial. Since mainland China has the death penalty and Hong Kong does not, where the case is reviewed has practical consequences for the outcome. Article 19 of the Basic Law stipulates that the Hong Kong courts "have jurisdiction over all cases in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region", and the Hong Kong government at the time had legitimate reasons to request extradition. However, the Hong Kong government not only did not make a request, but also actively provided evidence to the Chinese court, and Zhang Ziqiang was eventually sentenced to execution in Guangzhou. The methods and motives of the Hong Kong government in handling the case aroused many doubts at the time.

In recent years, doubts about the unfairness of law enforcement have often focused on whether there is a different level of severity between pro-government and anti-government opponents, making prosecution a tool of political repression, such as the conflict during the Occupy Movement mentioned above. As for the above-mentioned "Seven Police Cases", the persons involved were public officials who committed crimes during the performance of official duties and were charged with "intentionally causing serious bodily harm" rather than "torture" with a heavier penalty. Suspected of favoritism. In addition, it is also common to hear doubts about individual incidents, such as cases in which government officials violated traffic rules without being charged. Whether these cases are technically sufficient to constitute a prosecution can of course be discussed. However, the public image of officials and officials being guarded can be widely circulated, which at least reflects the society's high distrust of government law enforcement.

Finally, in recent years there has been a concern about law enforcement, directed at the Chinese government. In recent years, the public has often questioned that forces related to mainland China are carrying out various illegal acts in Hong Kong, including the Chinese police, the military, or gang members who have been bought off, but the Hong Kong government has not been able to find out. The disappearance of several Causeway Bay Bookstore clerks in 2015-16 has aroused widespread concern. Causeway Bay Bookstore is a famous bookstore in Hong Kong that sells books banned from mainland China. The owner of the bookstore, Li Bo, disappeared in Hong Kong at the end of December 2015. There is no record of departure at the port of entry and exit. A few days later, he returned to mainland China "by his own means" in a handwritten letter, and demanded that the case be dismissed when he met with the Hong Kong police in mainland China more than a month later. Lin Rongji, a clerk who also disappeared for a time, said that he had been detained by Shenzhen public security officers and was forced to "confess" in an interview. He also pointed out that Li Bo revealed that he was taken from Hong Kong involuntarily. In the face of such doubts and strong accusations, the Hong Kong government has yet to explain the ins and outs of the matter, and public opinion questioned whether it is not necessary to abide by the laws of Hong Kong as long as it is related to the Chinese government.

If all the above-mentioned doubts are true, it is certainly a step backwards from the perspective of the rule of law. Even if the accusations cannot be confirmed one by one, these doubts can be widely circulated, which is a serious social warning in itself. Returning to the discussion of regime recognition (see Question 14), it is quite inefficient and unstable for a regime to rely on force to maintain governance. At the very least, the ruled must feel that the regime's use of force and the system behind it is reasonable rather than arbitrary, and will voluntarily cooperate with the regime. On the contrary, when the ruled no longer trusts the use of force and the system behind it, the cost of governance will increase greatly, and the society will become unstable.

When the public believes that the government is accustomed to selective law enforcement, various social issues related to law enforcement will become political issues. For example, there is a fire in a farmland or an old building when there is a dispute over ownership or development. If the police cannot find out the truth immediately, some people will soon suspect that someone related to the developer deliberately set the fire and the police will cover up. Indulge. Even if the police find out that the fire was just an accident, some people will say that it is just to cover up the truth, and various conspiracy theories will continue to circulate. These speculations will undermine the credibility of the government and make governance more difficult. However, detaining "rumor makers" is only a temporary solution, and more importantly, it solves the problem of the government breaking its trust with the people. Therefore, a normal government and a normal police force should have improved the police-community relationship as much as possible so that the public can believe that the police are impartial.

Commentator Chen Yun once used the topic "How to Destroy a Team of Police", pointing out the serious consequences of the government's law enforcement losing the public's trust. He mentioned that when law enforcers treat protesters in the harshest way, the protests will not stop, but instead become more extreme. If "the protesters have the slightest change, they will be charged with assaulting the police. Anyway, the charges are the same, so why not fight?" Chen Yun's article was published in early 2010, and unfortunately, it foreshadowed the police-community relationship in Hong Kong in the future. .

The change in the status of the police involves a gap in the understanding of the rule of law between Hong Kong and the SAR government. Back in the Hong Kong-British era, the government took into account Hong Kong’s geographical junction at the forefront of the Cold War, and since the war has gradually established respect for the rule of law, such as managing the Communist Party and the Kuomintang forces equally, in order to win the society’s trust in the rulers. In the face of various political movements in mainland China, the institutional rationality and stability emphasized by the rule of law have become an important identity basis for Hong Kong people to distinguish themselves from mainland China. In the post-1997 period, the rule of law has become the last bulwark for Hong Kong people to resist autocracy and arbitrariness in the absence of comprehensive democracy. These ideas undoubtedly have an overly deified and romanticized dimension, but they once held a paramount position in the minds of the public. When the understanding of the rule of law is degraded from the value pursuit of "everyone is equal before the law" to the mechanical operation of "in short, breaking the law is wrong", the social shocks caused cannot be underestimated.

Further reading:

Wu Daming (2002): "The Ideal and Reality of the Rule of Law", edited by Xie Juncai, "Our Place, Our Time, Hong Kong Society New Edition", Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Chen Yun (2010): "How to Destroy a Team of Police", The Economic Journal, January 26, 2010, Cai Junwei, Li Jiaqiao (2018): "Legalization of Politics: The Rule of Law as Ideology", " Ming Pao, October 14, 2018.

Online resources:

Stand Report (2016) Causeway Bay Bookstore Five Disappearance Case Book, March 24, 2016, http://www.thestand.news/politics/Causeway Bay Bookstore Five Disappearance Case Book/ .

Stance Report (2018) Disciplinary Services Survey: Police Force's Net Satisfaction Worth at the Second Lowest in History, June 5, 2018, https://thestandnews.com/society/Disciplinary Services Poll Renewal-Police Satisfaction Net Worth Emergency Insertion - Second Lowest / .

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…