这是一个致力于介绍人类学观点、方法与行动的平台。 我们欢迎人类学学科相关的研究、翻译、书评、访谈、应机田野调查、多媒体创作等,期待共同思考、探讨我们的现实与当下。 Email: tyingknots2020@gmail.com 微信公众号:tying_knots

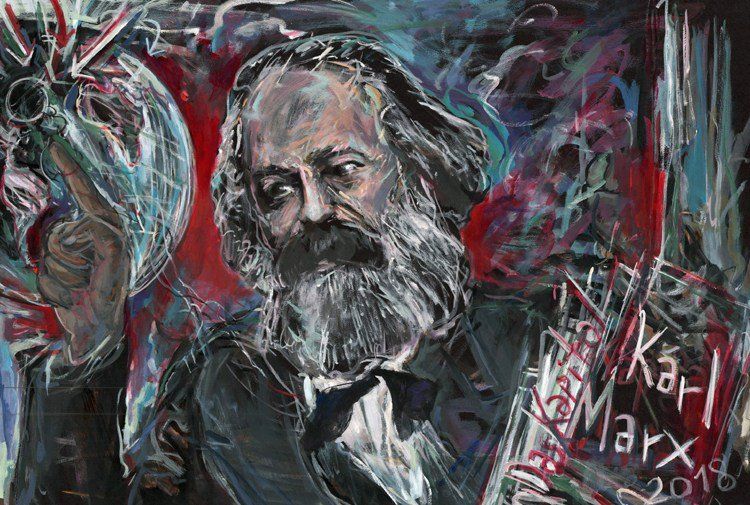

123 | Philosophical Anthropology | Marx's "Eurocentrism": Postcolonial Studies and Marxism (Part 1)

Anthropology and philosophy have infinitely traceable origins. Looking back at the history of the discipline since the 20th century, anthropologists' thinking relies heavily on the concepts and intellectual traditions of philosophy, while philosophy seeks inspiration from Western epistemology in exotic ethnography with an alternative. However, the imaginary division of labor with strong barriers keeps scholars stuck in their territory, anthropologists are content to be responsible for "special" ethnographic writing, and philosophers cite experience only to enrich "universal" analysis. .

It is necessary to review the intertwined history of philosophy and anthropology. The term anthropology has appeared as early as in ancient Greek philosophy. When philosophy was impacted by other thinking paradigms, the anthropological position and the tendency of philosophical anthropology to legislate for human beings are often the opposite of Kant, Scheler, Heidegger and other philosophical people. attacking position. Different from the philosophical and theological anthropological speculation that speculatively pursues "what is human", the practice of anthropology since modern times emphasizes contact with heterogeneous cultures through the field, and understanding, thinking and deep description in practice. Although this set of grammars was only systematized into the discipline of anthropology in the 20th century, it has already met philosophers in the circulation of history. It is the Carib that Rousseau met, Kant's travel diary in Konigsberg, Hegel. Zeitgeist found in the Haitian Revolution. In the era when modern anthropological theories were founded, classical anthropological phenomena, concepts and theories always stimulated the most outstanding philosophical minds of that era to constantly respond and think. Philosopher Lévy-Bruhl proposes a theory of interpenetrating thinking based on ethnographic material from around the world; the Pacific concept of Mana continues to resonate with the enlightenment of modern European reflection in the early 20th century; Wirtgen Stein has read The Golden Bough for many times, and the inspiration from it inspired a series of later thoughts on his "language game"; Mauss's gift theory is not only the most vital anthropological debate, but also constantly inspires Derrida, Marion ( Jean-Luc Marion and other philosophers continued to respond.

To study philosophy and anthropology is not to cling to the affinities of the two disciplines, but to go beyond the center of the West and the center of the academy, to build a continuity of experience and theory with local actors, and to reveal and understand the voices that have been repressed and ignored. And thinking, learning about ethics and reflection emerging from the field: as the journalist Foucault observed the "spiritual revolution" during the Iranian revolution, the "radical hope" taught by the Raven Indian warriors to Jonathan Lear Just as the Amazonian tribes inspired Viveiros de Castro's refocusing of ontology, Saba Mahmood in the Muslim women's reading movement in Egypt began a quest for freedom and ethics in modern society. Reflect. Whether it is to enrich the study of the human condition or reconstruct the understanding of the world, anthropology and philosophy need to shift from classics to practice, and restart communication and dialogue with a common focus on practice.

Philosophical Anthropology is a series of special topics jointly planned by Yushengzhi and the Philosophy Society. We try to open a model of shared learning and reading through joint translation and proofreading. This is a decentralized collaboration, the purpose is not to debate the difference between anthropology and philosophy, but to try to discuss with the authors of the article, how anthropology and philosophy are connected with each other in new ways in contemporary times, contribute to each other.

This work is Kolja Lindner's paper "Marx's "Eurocentrism" published in Radical Philosophy in 2010. This article describes in detail how Marx engaged in dialogue and reflection with the texts he came into contact with, and gradually transcended a stereotyped cognition of "Oriental civilization", and improved and deepened his theoretical framework from this point. This article will undoubtedly be invaluable to followers of Marxism and postcolonial theory.

Note: All the original texts of Marx in this article are from the second edition of the Complete Works of Marx and Engels by People's Publishing House.

Original author / Kolja Lindner, lecturer of German political theory at Sciences Po Paris Translation / Adam Typesetting / A Sheng, Hoshihara

"It will take a long time for those English idiots to get even a rough idea of the real conditions of the conquered peoples..."

Karl Marx, 1879

People have long spent a lot of time discussing Marx's "Eurocentrism". Scholars have debated his relationship to colonialism, his visions of Asian societies that reflected it, and his theories of social formation and social progress. Of these, Marx's 1853 essay on British colonization of India has received particular attention. In the field of Marxian Studies (MS) itself, the discussion of this topic is often either apologetic or purely semantic. With a few exceptions, almost no one has approached the subject from some sort of anti-authoritarian (herrschaftskritisch) [1] perspective, and no one has undertaken a systematic, holistic examination of Eurocentrism in his work. On this topic, the main contribution of Marxism is basically the academic editing and publication of his works, and this contribution provides the basis for some kind of balanced discussion.

Postcolonial studies have also taken up the topic, and critical voices are in the majority here. Marx was accused of defending a "Eurocentric model of political emancipation that had always ignored the lived experience of the colonized in non-Western societies" and "failed to develop his studies of India and Africa into a kind of imperialism. exhaustive analysis"; his analysis ignored "dispossessed groups like the colonized". [2] Edward Said, a giant in the study of Orientalism in the postcolonial field, even dismissed Marx's study as a "racist Orientalism of the non-Western world". [3] Correspondingly, in postcolonial studies, there is a strong tendency to denigrate Marx as a Eurocentric or even Orientalist thinker and a writer of historical philosophy. Against this background, I try to provide a dialogue between the two strands of Marxism and postcolonial studies in the following article,[4]. I'll start with a postcolonial critique of Eurocentrism (Part 1), and I'll start with a review of François Bernier's Travels in India - one of Marx's sources - This critique is crystallized in the analysis of . (Part III) One of my goals is to show what Markology can learn from postcolonial studies. I will also trace the trajectory of Marx's handling of "non-Western societies" from the texts we have access to throughout his life. (Parts 2, 4, 5, 6) (In Marx's writings, "non-Western" and "pre-colonial" and "pre-capitalist" are synonymous, so this article will do the same.) This retrospective will show that, Marx's approach to this issue had an evolutionary tendency that gradually led him to reject some Eurocentrist assumptions. Therefore, my article will also counter the hasty denigration of Marx by postcolonial studies.

Marx's gradual rejection of Eurocentrism was inseparable from a certain indelible theoretical preoccupation with various (pre-capitalist) land tenures (in non-Western societies). Because Marx himself never visited the non-Western worlds he wrote about, nor did he systematically study them empirically, his knowledge of these places came, in part, from very Eurocentric sources— — such as travel notes, congressional reports, theoretical writings, especially from the British. A prevailing view in these texts is that there is no private ownership of land in Asia. [5] This false Orientalist view has long been completely dismissed by historians. Depicting Marx's turn from Eurocentrism, therefore, also requires an assessment of the extent to which Marx escaped the usual notions of these "British donkeys."

01. The concept of "Eurocentrism"

Given the purpose of this article, it is reasonable to clarify the definition of "Eurocentrism". "Eurocentrism" has the following four dimensions -

a). An ethnocentrism that not only presupposes the superiority of Western society, but also attempts to justify this presumption in rational, scientific terms. Complementing this worldview is a certain desire to subject the world to this rationality. [6] This discourse often regards Europe as the political, economic, academic, and sometimes even racial center of the world. [7]

b). An "Orientalist" gaze towards the non-Western world. This gaze reflects more of what Said calls the "European, Western experience" than the prevailing, real situation in non-Western societies. In this gaze, the world is imagined from a regional perspective. The scales at which these different types of texts compile and convey impressions of the world outside Europe are not supported by objective reality, but are adorned by a Western European conceptual system. As a manifestation of economic, political, and military domination, an institutionally sanctioned geopolitical discourse emerged. Through homogenization, assimilation, etc., this discourse constructs the rest of the world as a kind of "other" that bears the brunt. (That is, "East" in Said's discourse and "Asian" in Marx's discourse.) And their inhabitants are transformed into distorted mirror images of Europeans themselves.

c). A concept of development through "a kind of false Eurocentrism . . . which uncritically takes the cultural and historical model of Western European capitalist society as the accepted standard across history and culture for all mankind". [8] Under this conception, the whole world is sometimes taken for granted to develop actively or passively according to the Western European model.

d). The erasure of non-European history, or more precisely, the influence of non-European history on European development. The discipline known as "global history" attempts to counter this offset by focusing on the interactions of different regions of the world. Thus, the field denies Europe's unique position and uses a certain Particularistic historiography to transform and "localize" the "universal conception" of Europe. The premise here is that "long before economic coherence was established in many parts of the world...a certain political and ideological conflict had risen on a global scale."[9] The repression of interwoven history with the world outside Europe” can be seen as a kind of Eurocentrism. [10]

The first two dimensions of Eurocentrism and racism are separated by a fine line. When ethnocentrism is articulated in a rhetoric of "essential difference", the boundaries of racism are crossed. The other two dimensions usually culminate in some kind of "arbitrary universalization of the particular."

02. Marx's 1853 Indian Essays

As part of a series of articles he published in the New York Daily Tribune (NYDT) in the early 1850s, Marx wrote his famous Indian essays. One of the hallmark views of these essays is that Marx saw Indian society as a static social structure. In his analysis, India's climatic conditions necessitated an artificial irrigation system. Under the influence of the low-level development of the society and the huge area of the country, this kind of irrigation system can only be constructed and managed by a centralized state authority. The distinguishing feature of this system is the high degree of unity of agriculture and manufacturing (handicrafts), which hinders the development of productive forces and hinders the creation of town centres. Marx saw the structure and isolation of rural communities in India as "the firm foundations of Eastern despotism and state stagnation". [11] In the end, he came to the conclusion that in this "Asiatic society", the state was the "true landlord" because of complex tax and land laws. [12]

Based on this vision of Indian society, Marx denounced British colonialism. This condemnation is filled with a certain ambivalence: "Britain," he argued, "had a double mission to accomplish in India: a destructive one, that of destroying the old Asian society; the other a constructive one, That is, laying the material foundations for a Western-style society in Asia.” [13] His starting point, obviously, was that colonialism contributed to the development of India. In his analysis, the strengthening of the Indian railway system [14] could allow for the further development of an overtaxed irrigation system. [15]

Furthermore, he assumed that the introduction of the steam engine and scientific methods of production would lead to the separation of rural agriculture and manufacturing. [16] Furthermore, according to Marx, India's integration into the world market would rescue the country from isolation. Finally, he estimates that British rule has led to the emergence of a new system based on private ownership of land. [17] In short, the economic foundations of the Indian village system were disintegrating, and colonial intervention had led to "the only social revolution ever seen in Asia". [18]

What is certain is that Marx's contradictory portrayal of colonialism contained the perception that India could only be freed from colonial shackles, or "the present ruling class in Great Britain itself was replaced by the industrial proletariat"[19] be able to profit from this technology transfer. Beyond that, Marx did not ignore the selfish ways of colonial power in developing productive forces, or the destructive side of colonialism. In his view, "No matter how sinful Britain may have committed, it was, after all, an unconscious tool of history when it created this revolution."[20] In other words, it was "creating the material foundation of a new world." when. [twenty one]

Marx's essay on India fits in all respects the definition of "Eurocentrism" discussed above. First, they one-sidedly see Europe as a society superior in technology, infrastructure, legal system, etc. In this respect, Marx gave a very special importance to private ownership of land. He postulated that it was the class divisions and class struggles brought about by property relations in Europe that made social progress possible. In contrast, in his view, the situation in India can only be described as "authoritarian" and "stagnant". In his description, the rural community of India is presented as a stagnant, self-enclosed being, isolated and lacking in communication with the outside world, opposed by a maharaja who is the owner of all the land. This depiction of rural Indian communities is deceptively deceptive—in fact, the fact that these communities themselves have class divisions is obscured. Furthermore, pre-colonial Indian society had an irrefutable productivity development and commodity production, so its social structure had to be seen as one full of conflict and dynamics. [22] As for the third dimension of Eurocentrism, Marx elevates a particular developmental model to the rank of universality: under his assumption, the "establishment of the Western social order in Asia" is a path to a The only way to a classless society. And he regards the road of creating this society as a common destiny of all mankind. [23] The problem with this assumption is not only that he does not take into account the development potential of India itself, but also that he sees India's social structure as merely an obstacle to progress, or at least an urgent need for radical change. Moreover, the overestimation of the European development model is based on a highly speculative assumption. The idea was that the situation in Europe could be replicated in India in its entirety, and thus could serve as a starting point for some kind of revolutionary movement. What Marx did not see was that under international capitalism, different regions of the world would be integrated into the world market in some unequal form, or would face different development possibilities and prospects. [24] Rather than "the pre-capitalist model is inevitably transformed by capitalist production relations", this is more of a question about "a representation of different modes of production constructed by power relations". [25]

As for the fourth dimension of Eurocentrism, in the eyes of students of global history, Marx's writings must only be regarded as "Eurocentrism." While Marx did emphasize the interaction of different regions of the world, his analysis was limited to the economic level. Moreover, with a few exceptions, this analysis is often one-sided, since generally he is only interested in the impact of the integration of non-European countries into world markets, not the (non-)European countries themselves. The history of India's intertwining with European countries outside the economic dimension, as unfolded in Chakrabarty's work, is completely unknown in Marx's work. [26]

03. The source of Marx's "Eurocentrism": François Bernier

In what follows, I will focus on the second dimension of Marx's "Eurocentrism", "Orientalizing the East". [27] As for the Eurocentrism in his sources, Marx can be said to have accepted it without reflection. In general, critical examination of these sources is precisely what Marxism tends to ignore. In travel writing, this source of information, this defect is particularly significant. With regard to travel writing, Said says: "Not only through large institutions like the East-West India Company, but also from the anecdotes of travelers, colonies are constructed and ethnocentric perspectives are established."[28] To date, even among writers concerned with Marx's "Eurocentrism," discussions of his sources have tended to focus on his use of classical political philosophy and political economy. [29] This is puzzling, not only because of the remarkable role that travel writing played in the development of the "Western imagination," but also because Marx himself wrote in a letter dated June 2, 1853 (in his letter to New York Three weeks before the publication of the first Indian article in the Daily Tribune), wrote to Engels: "There is no better man than François Bernier the Elder (who has written about the formation of cities in the East). He was a doctor with Aurangzeb for nine years) described better, more clearly, and more convincingly in "The Travels of the Great Mughal and Other Countries"." [30] Further, Marx used this A source supports his conclusion that the absence of private property in Asia "is even a real key to understanding the eastern kingdom". [31] Finally, in his reply to Marx four days later, Engels also defended his argument by citing Bernier that the absence of private ownership of land was due to local climatic and soil conditions. [32] And in his first article on India, Marx also adopted this argument. I shall explore Bernier's travels in detail here, not only because he has so far been ignored by Marxists, but also because this analysis, in my opinion, can provide an example of how Marxism can be learned from postcolonial studies— - A comprehensive study of Marx's "Eurocentrism" based on a critical examination of Marx's sources.

François Bernier (1620-1688) was a French physician and physicist who spent a total of twelve years in India. After his return to France in 1670, he wrote an influential travel account that was later translated into several European languages and reprinted in several editions. [33] This travelogue is also one of the origins of the concept of "Oriental Despotism". The concept is widespread and embraced by Western thinkers like Montesquieu and Hegel. [34] Bernier argues that, in India, only maharajas are the sole owners of land and use their income to support themselves:

"The royal palace is the sole owner of all the lands in his kingdom. From this it is certain that the income of capital cities like Delhi and Agra comes basically entirely from the vigilantes, and accordingly the maharaja is not allowed to go to the countryside for some time. not obey him.”[35]

This argument is a very typical Orientalist projection. It is based on subjective assumptions about the superiority of the European social and legal order and has nothing to do with the real situation in India. This "stupid ass", even if it is French and not British here, does not even have an "approximate" understanding of the "real situation" on the ground: extensive historical analysis has shown that in pre-colonial India, land ownership was not concentrated in Central, and land property can be transferred. In other words, private ownership of land exists objectively. [36] The denial of private ownership of land is only one aspect of the Orientalist rhetoric that pervades Bernier's travel accounts. His description of Indian superstitions is another part of the argument. Bernier portrays superstition as a key feature of Indian society. According to him, "Indians consult an astrologer in basically all matters."[37] This is not, in Stuhlman's opinion, a direct endorsement of European superiority, as Bernier also complained European superstition, and mocking those Western missionaries. [38] But I would retort that Bernier's Orientalism is exposed here. For example, in the text just cited, he does not attribute superstition to some individual social circle, and inevitably leaves the impression on European readers that Indian society is generally clouded by a mentality of ignorance , and it is this mentality that sets it apart from Europe. Partly out of this impression, Marx painted India as a stagnant state unable to progress, unable to attain modernity on its own terms.

Bernier's article also shows other Orientalist features. Here I agree with Stuhlman that although "race" is not a constructed category in his travelogue, "whiteness" is everywhere as a subtext. Bernier's descriptions tend to show a tendency towards essentialization. Therefore, we will read descriptions such as "Indian craftsmen are inherently lazy"[39], "most Indians are slow and very lazy"[40] and so on. Such an essential description is complemented by a typical oriental burst of enthusiasm. This passion sees the "Indian place" as "a little heaven on earth."[41] Bernier, however, distinguishes himself from the rest of the Orientalist mediocrity—he does not simply for himself learn from this He was excused from the routine practice of Orientalism, and he generously admitted that he did not understand Sanskrit. [42] Thus, his generalizations of India do not have a clear basis for standing; in any case, they are not based on indigenous sources. Not surprisingly, in the context of the coming European colonization of India, the purpose of this narrative is to subordinate the colonized areas to European interests. Therefore, here we must pay attention to the established tendencies of postcolonial research - bearing in mind the assumption that "the 'East' cannot speak for itself", holding a skeptical attitude towards the intellectuality of the classical original texts, and going Investigate the research object as a surrogate. [43] This is a key to understanding the colonial enterprise.

Another major point of Bernier's narrative, and one of concern for postcolonial studies, needs to be addressed here: the Western narrative of the phenomenon of "burning widows" in India. Without attempting to defend this tradition, Gayatri C. Spivak explains how these narratives limit the ability of subaltern women to speak and act. [44] In Bernier's travelogue, when one reads of his assistance to a widow threatened by fire, not only does one really notice his savage portrayal of her morbidity and hysteria in the narrative, but also in it The "barbaric customs" of these "idolatry people" were severely criticized. [45] Thus, for the Frenchman, the aid of the Indian widow was a sign of the etiquette of a cultured society. [46] Ultimately, the ideological shackles this argument placed on these women were much heavier than the colonial situation itself. [47]

Thus, Bernier's narrative can be reduced to an "imaginative examination of what is 'Oriental'". [48] Like any other Orientalist discourse, his description not only projects an image of the "other" but also helps construct an image of the "self". In this way, a "superstitious" and "stagnant" India is opposed to a contemporary Western society "disenchanted" by violent social unrest. The "lazy" and "paradise" fantasies of India made the whole country a foil for an early capitalist Western Europe that was "hard-working", "active" and "self-denying". The final result is a stark contrast between "Asian despotism" and Europe's "enlightened despotism", "barbaric customs" and "cultured society". [49]

In short, Marx should have done better - he should have undertaken a critical examination of his source rather than extracting its content as a central element in his assessment of India's social structure. However, despite his failure to do so, the difference between him and Bernier is still evident. He never crossed the bottom line of "essentialization" - the bottom line between Orientalism and racism. While he does take certain "facts" from Orientalist or racist sources when dealing with colonialism and integrates them into what he is in many respects "Eurocentric"[50], about "progress" in the discussion. But in fact, he did not reproduce the "essential" tendencies in these sources. Of course, this step is indeed problematic and naive. But it does prove that Marx's discussion of colonialism and slavery did not take place in a very anti-authoritarian context—a context in which treatment of the extremely complex issue of racism would Put it in an independent position (attribute a place of its own), and never think of reducing this problem to the problem of division of labor. [51] Nonetheless, based on the above discussion, the assertion that "Marx himself was a racist"[52] seems unfounded to me.

In any event, there is no doubt that Marx in the early 1850s neither adopted a discerning, non-Eurocentrist perspective on colonialism, nor did he adopt some of the source of accurate knowledge of society. (These sources also gave him a real sense of the social upheaval caused by colonial rule.) But in the 1860s and beyond, he wrote some more complete accounts of these societies. In what follows, I will accordingly attempt to point out how he developed a more nuanced picture of colonial expansion, especially through his press releases in the 1860s, to show how he cut at least two dimensions of Eurocentrism . (Part IV) Afterwards, I will briefly comment on some Orientalist ideas in Marx's political economy.

04. India and Ireland: The Beginning of Marx's Turn from Eurocentrism

Scholars have long debated whether it was Marx's work on British colonial India that first led him to take a more cautious, balanced stance on the issue, or whether his work on colonial Ireland played that role. According to Pranav Jani, Marx had overcome his Eurocentrism in his study of the Great Indian Revolt of 1857-59. Indeed, he partially acknowledged the justification of the uprising[53] and mentioned the difficulty of using "Western concepts" to understand the Indian situation. However, Jani's argument is unfounded. He argues[54] that the negative British assumptions about the colonized, which Marx had initially accepted, have gradually been replaced in his essay on the Indian uprising by an insight that "the Indian commoners are capable of autonomous action" . Even more telling is that, unlike the Indian Essays of 1853, these 1857, 58 essays are primarily informational and do not contain as much theory, speculation, and sharp political analysis as they once did. Nonetheless, the perspective adopted by Marx in his writings of the late 1850s was mainly military and strategic[55] - and it was Engels' text on the issue of Indian rebels that underpinned this perspective. Stereotypes, and an appeal to a habitual sense of Western superiority. Please understand my dissent, Jani, but Marx could hardly even "take a critical attitude to comment on the military logistics and operational plans of the British colonial powers", let alone an "anti-Eurocentrism perspective". turned". In addition to this, Reinhard Kößler rightly points out that, in Marx's assessment, the uprising was possible in the first place because the British created a corps of soldiers. Here, resistance to colonial rule may be seen as the result of "the process of innovation given the kinetic energy of the colonial process" rather than "as an extension of the class struggle of the colonized state itself, or as a result of a The particular structure created by the situation and the revolutionary role of capitalist penetration". [56]

On this basis, Marx's writings on the Indian uprisings can hardly be seen as a sign that he was on the road to breaking with Eurocentrism. However, I agree with Bipan Chandra[57] that by the 1860s at the latest, Marx (and Engels) had developed a Awareness of underdevelopment. This realization was formed in their research on Ireland. Here Marx describes the suppression of Irish industry[58], the systematic exclusion of Irish agricultural markets, the outbreak of famine and rebellion, and the immigration of Irish to North America and Australia. [59] However, his assessment of the prospects for development brought about by colonialism played a more decisive role in his shift of perspective than his emphasis on the use of violence in Britain. In the case of India, Marx observed that destruction and progress complement each other, which explains his contradictory assessment of Britain's "dual mission". In contrast, the Irish case taught him that what colonialism ultimately brought to the colonies was an unequal integration into the world market, and in fact hindered rather than advanced the establishment of capitalist relations of production. According to Marx, Ireland was the victim of a murderous "super-exploitation" - militarily, agriculturally, and demographically. [60] What was crucial to the accumulation process of the "mother country" was not its socio-economic development, but its colonial status.

Interestingly, Marx draws the political consequences from this insight - he concludes that in order to "accelerate social progress in Europe" a social struggle will have to be waged in Ireland. [61] He even went so far as to postulate: "Not in England, but only in Ireland could the decisive blow to the British ruling class (and this would be decisive for the labor movement all over the world) was possible."[62] Marx's view here is indeed still dominated by a teleological conception of progress. But, in contrast to India, which was thought to be free from colonial shackles "only when the present ruling class in its own country was replaced by the industrial proletariat," in Ireland's case local political upheaval was given "to let the colonists their own The country produces revolutionary progress" is of vital importance. So in my opinion, it is not an exaggeration to say that Marx achieved a "correction" of attitudes on colonialism and national liberation at the latest in the late 1860s. [63] And it was this change in Marx's attitude that led to his first break with Eurocentrism. [64] No doubt he still sees Britain as a superior society, but he no longer sees British colonial rule as a source of progress for the rest of the world. As a result, the "universalization of the Western social order" that the Indian case attempts to illustrate is gradually beginning to disintegrate. Finally, Marx now begins to conceive of the interaction of different regions of the world in a different way, rather than the completely economic, linear way of thinking.

(To be continued)

Posted in Philosophical Anthropology , Compilation

Latest articles (continuously updated)

114. Reading Football: A Guide to Watching the Game from Anthropology (Part 2)

115. Marginal Domestication - Caring for Crop Wild Relatives and Lineages

116. The inequality between men and women is contrary to Islam

117. Sullins as a Left

118. Philosophical Anthropology: The Way of Diet (Part 1)

119. Bottom Beijing: A Conversation with Ai Hua

120. Why we need to rethink monogamy

121. Philosophical Anthropology: The Way of Diet (Part 2)

122. Killing sons and offering sacrifices, are you crazy?

123. Philosophical Anthropology | Marx's "Eurocentrism": Postcolonial Studies and Marxism (Part 1)

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…