connect the dots.

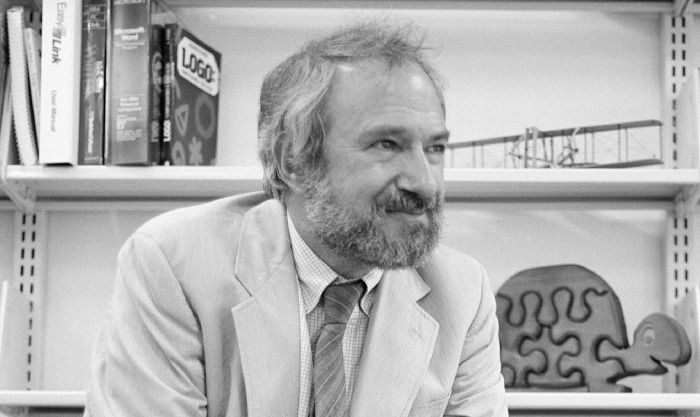

New Mindstorms Prologue: The Seeds Planted by Seymour Papert

The author is Mitchel Resnick, father of programming for children, professor of learning research at the MIT Media Lab, and author of Lifelong Kindergarten . This article is the preface he wrote for the new edition of Mindstorms .

Now, 40 years after the publicationof Mindstorms (Chinese version is "Powered by Computers" by Seymour Papert), when I reread it, I have two mutual Contradictory responses.

On the one hand, many of Seymour's ideas, seen as radical in 1980, are now part of the educational mainstream.

On the other hand, many of Seymour's dreams remain unfulfilled.

Why can Seymour's thinking be so aligned with today's reality, yet so disconnected from it?

To understand this seemingly paradoxical issue, look back to 1980 when Mindstorms was published. At the time, the first personal computer had just been developed. No phones or tablets, or even laptops. At that time there was no network (Web), and few people had heard of the Internet (Internet). So to predict, as Seymour did at the time, that millions of children around the world would soon be interacting with digital technology on a daily basis, as they are now, is indeed radical.

Even more radical is the way Seymour imagines children using computers. Of the small group of researchers who began considering the use of computers in K-12 education in the 1980s, most focused on "computer-aided instruction," in which computers act as traditional teachers Role: Provide information and guidance to students, conduct quizzes to measure what students have learned, and then adjust subsequent instruction based on student responses.

In Mindstorms, Seymour makes a very different point. For Seymour, computers are not a replacement for teachers, but a new medium that children can use to make things and express themselves. In Mindstorms, Seymour opposes the computer-aided teaching method that "the computer is being used to program the child", and advocates an alternative "the computer is being used to program the child" (the child programs the computer).

In the decades since Mindstorms was published, Seymour's thinking on educational technology has had an increasing impact. Schools around the world are now adding makerspaces and programming courses, offering students opportunities few could have imagined in 1980. Seymour's work should be seen as the intellectual inspiration for the Maker Movement and the Coding Movement.

However, if Seymour were alive today, I have no doubt he would have been very frustrated with the way production and coding were introduced in schools. Seymour would see most current initiatives as "technocentric" (a term popularized by Seymour). That said, these initiatives are too focused on helping children develop technical skills: how to use 3D printers, how to define algorithms, how to write efficient computer code.

For Seymour, technical skills were never the goal. In Mindstorms, he wrote: "my central focus is not on the machine but on the mind." Seymour was certainly interested in machines and new technologies, But only if they support learning or bring new insights into it.

A considerable part of Mindstorms focuses on Logo, the first programming language specifically designed for children. But at the heart of Mindstorms are Seymour's ideas about education and learning, not technical issues. In it, he laid the intellectual foundation for what he later named "constructionism" in educational theory. The theory builds on the work of the great child development pioneer Jean Piaget , with whom Seymour collaborated in the early 1960s. Piaget's great insight was that knowledge is not passed on from teachers to learners, but children are constantly constructing knowledge through daily interactions with people and things around them. Seymour's theory of constructivism adds a second way of constructing, arguing that children construct knowledge most effectively when they are actively involved in constructing things in the world. As children build things in the world, they build new ideas and theories in their heads, which motivates them to build new things in the world, and so on.

Seymour saw a wealth of learning opportunities in all the different types of "construction": building sandcastles on the beach, writing stories in a journal, drawing in a sketchbook. Why is Seymour so interested in computing? Because he recognizes that computer technology can greatly expand the scope of what and how children create. With computers, children can create things that move, interact, and change over time, such as animations, simulations, and interactive games. In the process, children can gain new insights into the workings of the dynamic systems of the world around them - including the workings of their own minds. In addition, computers enable children to modify, reproduce, record and share their creations in unprecedented ways, giving them new ways to explore and understand the creative process.

To Seymour's dismay, people seemed to hear only part of his message, often focusing on technology and ignoring ideas. In an essay 20 years after Mindstorms was published, Seymour laments that the three parts of the book's subtitle - Children, Computers, And Powerful Ideas - have not been given equal The emphasis: "Most educators (and those who hate it) who find inspiration and affirmation in the book discuss the book as if it were about children and computers, as if the third part was a Sound bite, that cliché that pervades educational technology discourse. I didn’t mean it: I actually thought I was writing a book about ideas! ”

Of course, proponents of today's "learn-to-code" initiatives will say that they are also interested in ideas, not just technical skills. Many of them design their work around the concept of "computational thinking" - designed to introduce children to problem-solving strategies from the field of computer science but applicable to many other fields. There is certainly value in learning problem-solving strategies. But Seymour had a bigger, broader vision. Not only does he support children in developing their own minds, but he also supports children in developing their own voices.

Seymour sees computers not only as tools for problem solving, but also as a medium of expression. He believes that learning to code is similar to learning to write, giving children new ways to organize and express their ideas. Seymour wants to help children of all backgrounds have the opportunity to express and share their ideas so they can become full and active participants in society.

With all the excitement surrounding the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) in K-12 education, what does Seymour think? In Chapter 7 of Mindstorms, Seymour describes how AI research has been a major source of inspiration for his work in education and learning. Likewise, Seymour's 1980 book seems prescient. But, again, I believe, Seymour would be very frustrated with how AI is doing in education today. Seymour is interested in applying the ideas of artificial intelligence to engage children in thinking about their own minds, as well as learning about their own learning. Most AI education programs today have a very different set of goals, focusing on the use of machine intelligence rather than the understanding of human intelligence.

So what limits the spread of Seymour's ideas? Why didn't his ideas have a bigger impact? One of the challenges is the general resistance to change in the education system. But there are also challenges in the way Seymour's ideas are propagated, supported, and interpreted. For example, Seymour's frequent use of examples from mathematics and computer science has led some to interpret his ideas too narrowly, although Seymour hopes his ideas can be applied to all disciplines. Seymour's frequent emphasis on examples of how children can create and learn on their own has led some to try to implement his ideas without paying enough attention to the role of teachers, parents and peers in the learning process.

When I think about the spread of Seymour's ideas, I prefer to think of the ideas Seymour planted as seeds planted by farmers. Some are mathematical ideas, some are pedagogical ideas, some are technical ideas, and some are epistemological ideas. Seymour's ideas spread around the world like wild flowers. Some take root in a few places but not in others. Some of his seeds are still sleeping in the ground.

I am part of a community of researchers and educators who continue to believe deeply in Seymour's ideas and vision. We are committed to nurturing the seeds Seymour sowed and working to provide the right conditions for them to grow. I worked closely with Seymour for many years, first as a graduate student at MIT and then as a faculty colleague. My research today is still heavily influenced by Seymour's ideas, and I continue to explore how to support his ideas in different learning situations. As a framework for my work, I have developed a set of four guiding principles, all inspired by Seymour's thinking:

- Projects. Seymour's point of view is "projects over problems" . Of course, Seymour understood the importance of problem solving. But he believes that people are most effective at problem-solving (and learning new concepts and strategies) when they are actively engaged in meaningful projects. Many times, schools start by teaching concepts to students before giving students the opportunity to work on projects. Seymour believes that it is best for children to learn new ideas through a project, not before the project begins. Passion. In the introduction to Mindstorms, Seymour describes how his childhood fascination with gears provided him with a way to explore important mathematical concepts. To me, the most important and memorable line in the preface is Seymour's writing, "I fell in love with the gears." Seymour understands the importance of learners building interest and passion sex. He knows that when people are working on projects they love, they work longer, harder, and develop deeper connections with ideas. Seymour once said, "Education has very little to do with explanation, it has to do with engagement, with falling in love with the material." Peers. In the final chapter of Mindstorms, titled "Images of the Learning Society," Seymour writes about the Brazilian samba school, where people gather for the annual carnival Create music and dance performances. What interests Seymour most is the way the samba school brings people of all ages and experience levels together. Children and adults, novices and experts, all work together and learn from each other. For Seymour, this peer-based learning is at the heart of a learning (type) society. Seymour, like Piaget before him, was sometimes criticized for focusing too much on the individual learner. But what he wrote about the samba school showed another side of Seymour. Technology in the Mindstorms era wasn’t quite ready for the kind of peer-based online collaboration we see today, but Seymour recognized the importance of the social dimension of learning. Game (Play). Often, people associate games with laughter and fun. But for Seymour, the game is more than that. It involves experimenting, taking risks, testing boundaries, and adjusting back and forth when things go wrong. Seymour sometimes calls this process "hard fun ." He realized that kids don't want things to be easy: they're willing to work really hard on what they find meaningful. And Seymour didn't just encourage others to play and make them have fun; he lived that life himself. He was always playing with ideas, wrestling with ideas, experimenting with ideas. I've never met someone who was so playful and so serious about ideas.

Seymour is more than a mathematician, educator, philosopher and computer scientist. He is also an activist. Since his boyhood in the 1940s, when he battled apartheid in his native South Africa, Seymour has sought to bring about change. When he launches new educational projects, he often exclaims "Now is the time!". He is a man with lofty ideals and hopes for big changes. In Mindstorms and other writings, he advocates for a revolutionary change in the way we think about children, learning, and education. In the 40 years since Mindstorms came out, the changes have been more evolutionary than revolutionary. Many of Seymour's dreams did not come true.

But I believe the environment is becoming more and more fertile for the many seeds Seymour sowed. There is a growing recognition that the education system cannot meet the needs of today's rapidly changing society. More education reformers are advocating for change that aligns with Seymour's philosophy, giving children more opportunities to explore, experiment, and express themselves so they can develop into creative thinkers. These changes are incremental rather than revolutionary, but long-term trends are moving in the direction of Seymour's vision.

As you read Mindstorms, don't get distracted by the details of the 1980s technology described in the book. Instead, think about how Seymour's ideas can be incorporated into today's discussions of education strategy and policy. Think about what you can do to nurture the seeds Seymour sowed.

Compiled from: The Seeds That Seymour Sowed

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…