需要藍天

Missing Xixi on Mulan Field

It has been a year since Teacher Xixi left. On Sunday (December 17), an event was held at Fude House to commemorate the first anniversary of Xixi’s death. In addition to reading Xixi's works, teacher He Furen also introduced the works that Xixi will publish and also previewed the establishment of Xixi Space.

Looking back on this year, although Teacher Xixi has passed away, her words still surround readers, as if she has never left.

Since I am commemorating this day in Xixi, I will write the following article as my thoughts on a Hong Kong writer. This time I chose to read "The Whistle Deer".

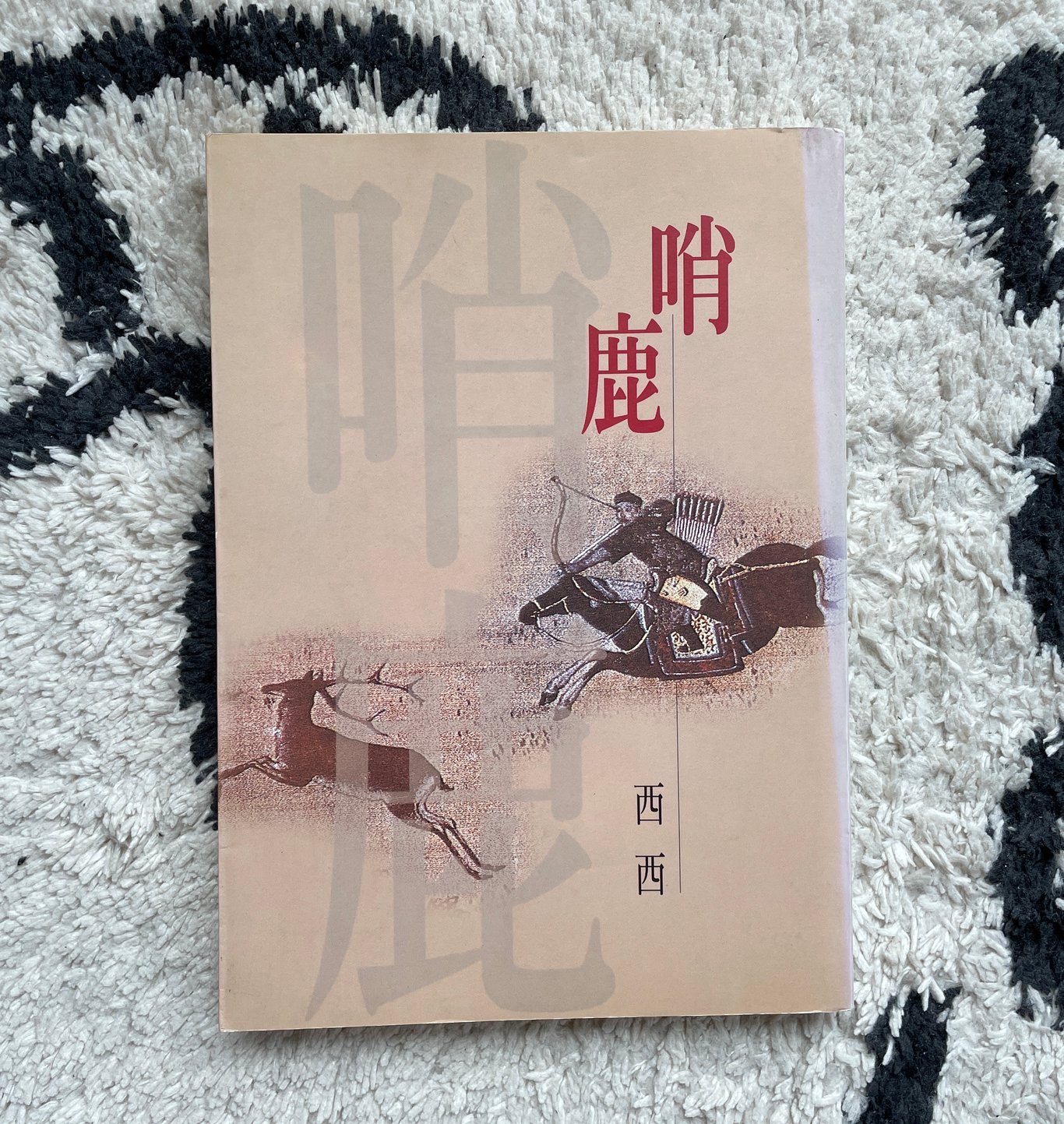

"Whistle Deer" is not mentioned by as many people as Xixi's other works, such as "A Woman Like Me", "My City", and "Mourning Breasts". Perhaps novels with historical themes are difficult for readers.

One day I listened to the Xixi commemorative special episode of "Open Book Music" [Note 1] and learned about the time when "The Whistle Deer" was written. Dr. Liu Weicheng mentioned that in 1982, Xixi published the short story collection "Spring Hope" [Note 2], the poetry collection "Stone Chime" [Note 3], and the novel "The Whistle Deer" [Note 4]. That year can be said to be a fruitful period for Xixi's works.

The story of "The Sentinel Deer" is based on the Qing Dynasty Emperor Qianlong and a commoner family. This civilian family is actually composed of two ethnic groups: Manchu and Han: father Wang Agui is Han and has lived in Manchu areas, and his Manchu name is Emuke; mother Cuihua is Manchu, formerly known as Ayijilen; the protagonist's son Lainiu, The Manchu name is Amutai. Interestingly, in folk stories, Qianlong is always said to be the son of a Manchu (i.e. Yongzheng) and a Han woman (i.e. Lu Siniang). Just in contrast to Amutai.

"Whistle deer" refers to a hunter using a long whistle to imitate the sound of a deer to lure other deer, and then shoot the deer. It's called "Mulan" in Manchu. Xixi imagined a long novel from a picture of Mulan painted by Castiglione and others. Castiglione's painting is divided into four sections; Xixi's novel is also divided into four chapters: each chapter describes Qianlong's life and Amutai's life respectively, and then the two of them slowly move from the two ends to the center: Shaolu Field. However, the trajectories of the two protagonists pass by each other like two train tracks without any intersection.

The author is meticulous in describing Qianlong's living conditions. One of the passages in which the author describes the summer resort is as follows:

The summer resort looks cooler and simpler in the rain. Qianlong was sitting in the "Hukou Yanyu Tower" in "Ruyizhou". Looking up, he could see the mountains on all sides of the villa. Each mountain has a different appearance, just like the name of the mountain itself. Some peaks are like giants squatting, so they are called Luohan Mountain; some peaks are like frogs with their heads raised, so they are called Toad Rocks; some peaks are like sticks and hammers, so they are called Qingchui Mountains. There are also Jiguan Mountain, Tianqiao Mountain, Jinshan Mountain, and Black Mountain. Each peak is majestic and abrupt. ⋯⋯(page 89)

Reading this paragraph now may feel cumbersome, because as long as you go online, you can find a large number of photo introductions of summer resorts, and there is no need to express them in words. But don’t forget, “Whistle Deer” was published in 1982. There was no Internet at that time, and television was just becoming popular. At that time, Hong Kong people were beginning to travel abroad and learn about China and the world through various channels. Books are one of the ways to understand the world. I think readers at that time could understand the appearance of the summer resort through Xixi's words, as a kind of "tourist" attraction through words.

The characters in the book, whether they are Qianlong or Wang Agui's family, all see the world as "simple". Although Qianlong was busy with everything and felt that he was doing a good job, sometimes he did not understand why countless people were still living in poverty in this peaceful and prosperous age:

⋯⋯ Countless people are still living in poverty. And what is the reason for this? Don’t the tenants have land to cultivate? Aren’t taxes reduced? Isn’t the river channel dredged? Aren’t the lazy people, the humble households, the happy people, and the untouchables already open to the good? Isn’t shipping booming? Aren’t merchants free to buy and sell? Isn’t business booming in all walks of life? So why is there still a folk proverb that says "the people are still in Rehe"? Of course, this Rehe does not purely refer to Rehe in Chengde. ⋯⋯(page 95)

Xixi uses "Rehe" here to express two meanings. On the one hand, it refers to the place where the summer resort is located; on the other hand, it means "in dire straits." Not only did the people's lives not improve due to the imperial policy, On the contrary, it is worse. What’s the explanation? Later, he expressed that he understood that it was the officials who made the people not live well. However, he only knew but did not take action, just like he read the memorial every day and then wrote "I understand" and "noted". And after that? there is none left. His world, to use modern parlance, is "in the clouds."

If it's just in the "cloud", it might be fine. In fact, his world is a show he wants to watch. The book describes a street in the Old Summer Palace. As long as Qianlong issued an order, the street would immediately become lively, but everything was false (page 9).

On the other side, Wang Agui, who is very close to the ground, and his son, both maintain their "simpleness": look at things "simplely" and live "simplely". Wang Agui works in the fields to obtain the necessities of life and support his wife and children. He longed for a cow to help him, so he changed his name to "Lai Niu". His son Lai Niu, Amutai, worked hard as a deer whistler to assist the emperor in hunting. But fate never allowed them to live a "simple" life: Wang Agui's farmland was taken away by the government. He did not want to be a domestic slave, so he had no choice but to flee the place and go to another place to work in coal mining. As a result, the coal kiln fell down and died. Lai Niu was originally going to assist Qianlong in hunting deer, but he was killed by a poisonous needle that night, just for a mission he didn't know but had to perform: to assassinate Qianlong.

When Amutai learned that his father died under the coal kiln, he was already shocked; when he heard that the "murderer" who killed his father was Emperor Qianlong, he was even more puzzled; when a stranger said that the emperor was a Manchu, he had killed He didn't understand even more when thousands of Han people had to avenge the Han people. Is the Han emperor better than the Manchu emperor? Will the world be peaceful if a Han becomes emperor?

The author uses a series of questions to express Amutai's doubts. These self-questions make readers feel "heavy" and under tremendous pressure, because Amutai is a kind-hearted person and he uses his "simple" worldview to analyze. This kind of thinking is no different from Qianlong's "simple". However, Amutai's world at that moment was so real compared with Qianlong's world.

Xixi is good at using light brushstrokes to describe heavy things. For example, Wang Agui died in front of a coal kiln. She imagined herself under a snow-capped mountain and watched the snow fall. After Amutai was poisoned, what he remembered was:

⋯⋯None of them knew that Amutai missed them so much. Amutai saw that the stars in the sky suddenly blurred, as if all the stars were swimming in the river together. Amutai suddenly heard his mother’s voice: Amutai, don’t cry, Amutai, don’t cry. (page 179)

The lightness of the snow and stars, and the weight of the two deaths, form a pendulum-like contrast, and the reader falls into sadness. However, Amutai's death was not important enough to put the emperor's hunt on hold. The lives of ordinary people are as insignificant as dirt in the eyes of the powerful.

Emperors and common people live under the same sky, but their worldviews are so different, just like the sentence in the Guangdong proverb: "One kind of rice can feed a hundred kinds of people." After reading it, I was reminded of Wei Desheng's "Sedek. Balai". The Japanese and Seediq people fought on different sides in the Wushe incident, but in fact, they believed in the same sky. Xixi uses the story of the emperor's hunting to expand from one person (emperor) to a generation, a sad generation.

Now that I have finished reading this story and look around again, it still feels so familiar!

~~~~~~~~~

[Note 1] "Open Book Music" Xixi Memorial Special (Part 2) | Guest: Dr. Liu Weicheng—— https://podcast.rthk.hk/podcast/item.php?pid=541&eid=213037&year=2022&list=1&lang=zh-CN

[Note 2] Short story collection "Spring Hope"——

https://xixicity.org/zh-hant/timeline-posts/%e7%9f%ad%e7%af%87%e5%b0%8f%e8%aa%aa%e9%9b%86%e3%80 %8a%e6%98%a5%e6%9c%9b%e3%80%8b%ef%bc%88%e7%b4%a0%e8%91%89%e5%87%ba%e7%89%88 %e7%a4%be%ef%bc%89%e5%87%ba%e7%89%88/

[Note 3] Poetry collection "Stone Chime"——

https://xixicity.org/zh-hant/timeline-posts/%E8%A9%A9%E9%9B%86%E3%80%8A%E7%9F%B3%E7%A3%AC%E3%80 %8B%EF%BC%88%E7%B4%A0%E8%91%89%E5%87%BA%E7%89%88%E7%A4%BE%EF%BC%89%E5%87%BA %E7%89%88/

[Note 4] The novel "The Whistle Deer"——

https://xixicity.org/zh-hant/timeline-posts/%e9%95%b7%e7%af%87%e5%b0%8f%e8%aa%aa%e3%80%8a%e5%93 %a8%e9%b9%bf%e3%80%8b%ef%bc%88%e7%b4%a0%e8%91%89%e5%87%ba%e7%89%88%e7%a4%be %ef%bc%89%e5%87%ba%e7%89%88/

"Whistle Deer" (from the blog)——

https://www.books.com.tw/products/0010119801

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…