如果您對馬克思主義有興趣而想學習或研究,或者可以為翻譯馬克思主義的文章作出貢獻,我們真誠地歡迎您的加入。 網址:https://www.marxists.org/chinese/index.html 臉書:https://www.facebook.com/marxists.internet.archive.chinese

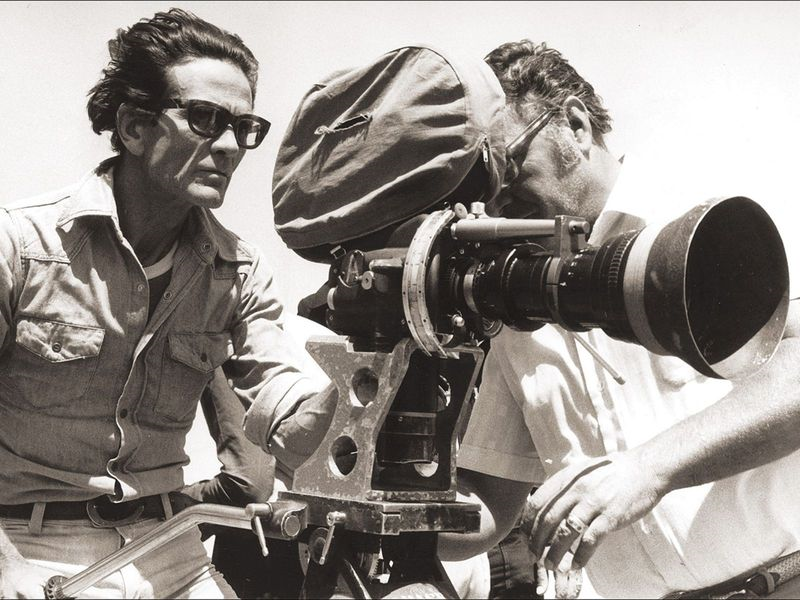

Remembering Pier Paolo Pasolini, Italian writer, poet and director

﹝Italy﹞Luca Peretti

Zhuotuo translation, Rituwu, On-duty Volunteer School

A look back at the life and political thought of Italian writer, poet, and director Pierre Paolo Pasolini, an unorthodox communist.

In 1975, the day after Pier Paolo Pasolini was brutally murdered, L'Unitá , the organ of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), used the word "vero militante" to describe him, Means true warrior. Just a few decades ago, in the same newspaper, an op-ed led to Pasolini's expulsion from the Italian Communist Party.

In 1949, the regional leader of the party, Ferdinando Mautino, denounced: "Those various followers of Gide and Sartre, some of whose ideas and philosophies have produced Harmful influences...they claim to be progressives, but in fact accept the most harmful aspects of bourgeois corruption." The Italian Communist Party expelled Pasolini on the grounds of these so-called "harmful influences", but in fact Because he is gay.

Pasolini was not an orthodox communist, having been a fellow Communist throughout his adult life. His complex relationship with the Italian Communist Party reflects how he interacts with other leftists at home and abroad: from his skeptical support of the student movement to his unreserved fascination with America's New Left.

In the English-speaking world, Pasolini is best known for his work as a filmmaker. Between 1960 and 1975, he was mainly active in the film industry, but dabbled in other areas as well. His novels and poems have also been translated and studied to a certain extent, though these works have received much less critical attention. Some of his theatrical productions - trivial but by no means insignificant - have also been translated into English. Little is known, however, about Pasolini's side as a public intellectual, a status that has given him such a prominent place in Italian culture.

Pasolini's Rome

Isolated by the Italian Communist Party (who was still largely anti-gay at the time) and ostracized in his own homeland in the wake of the gay scandal, Pasolini left his home in northern Italy and set out for Rome. For him, it was a new beginning: he had developed a strong bond with the city, and the Borgate area in particular. Borgate refers to the outlying regions of Rome, inhabited by the poor lower classes, which Pasolini called "grandiose plebeian metropolis". The Borgate area has inspired Pasolini a lot, inspired him to write many novels and films, but because it seemed to him a struggling third world, it also became a place for his politics. , cultural workplace.

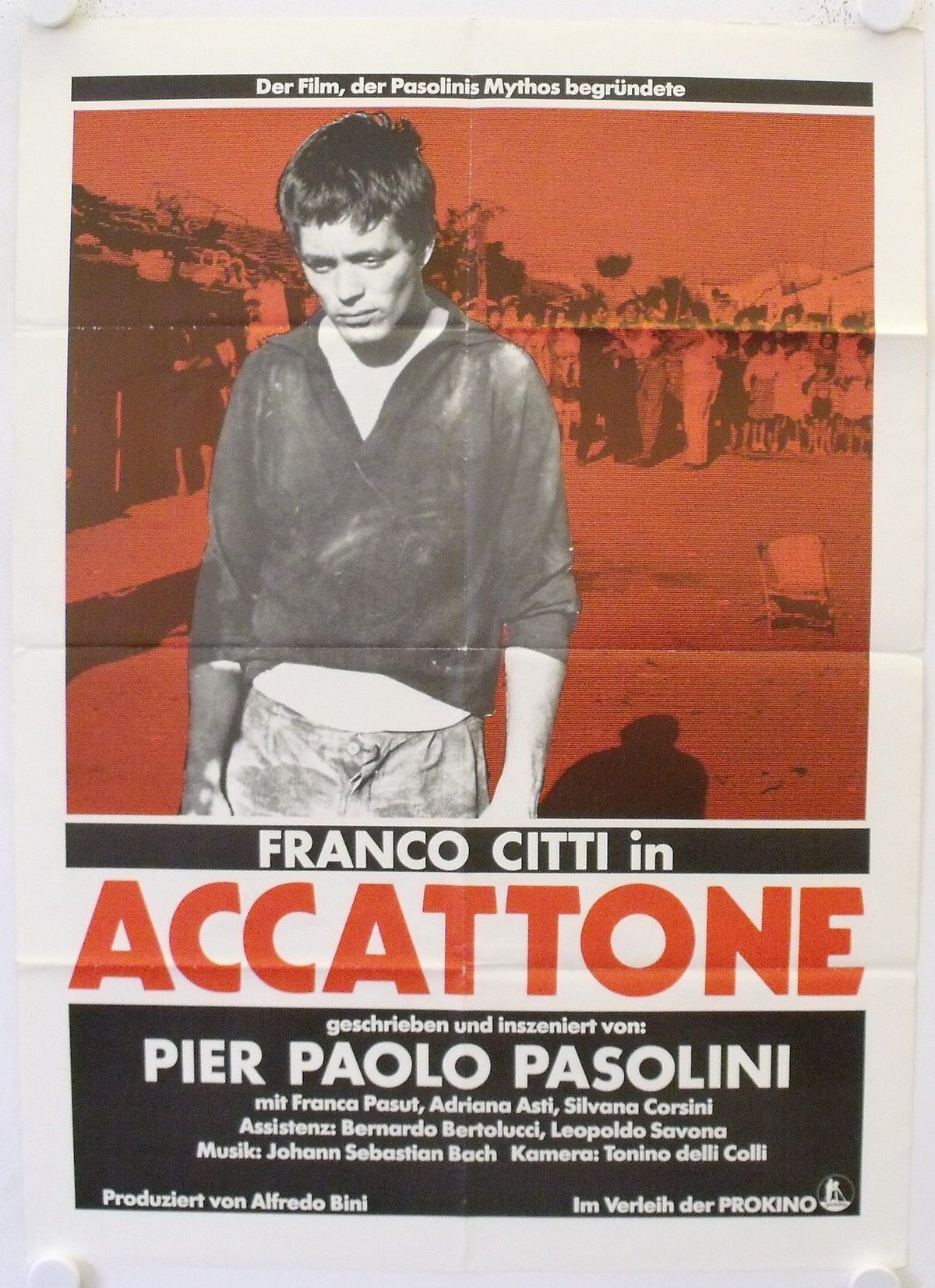

In the novel " Street Kids " or " A Violent Life ", or the movie " Accattone " or " Mamma Roma ", we should not look for Marxist themes, because All of these works are about the Roman underclass. Instead, through these works, Pasolini presents the viewer with a transformation in progress: the end of an old era that once belonged to those southern farmers who slowly lost their centuries-long traditions, This era also belonged to the Romans, who lived in groups that were abandoned by the Vatican and other regimes.

Pasolini was very interested in these outcasts, so he gave them old feelings. As he said in his last interview hours before his misfortune, he misses "those poor and real people who struggled to bring down the masters (bosses) on their heads and failed to become new masters. Because of their Excluded from everything, so they remain free."

He found that the culture that annihilated the old did not bring about new improvements: dehumanized, homogenized, and degenerate capitalism, a genocide (as he put it) that emptied the inhabitants of Borgate, their Has its own language and even its own (though not always political) unity. Today, as the world around them changes, those who fail to become petty bourgeois lose their sense of belonging.

Unlike many among the Italian left intellectuals who view the working and lower classes either in an almost mythical way or as monolithic, Pasolini has a realistic view of the people he describes. understanding. If his views were sometimes vaguely traditional, the broad left would not ignore it, in other words, as he said in an article on the Israeli-Palestinian issue, "(Communism They would never admit their hatred of the rogue proletariat and the poor.” In 1959, he called for the CPC to become “the 'party of the poor': a party, so to speak, of the lower proletariat. "

Pasolini and the Communists

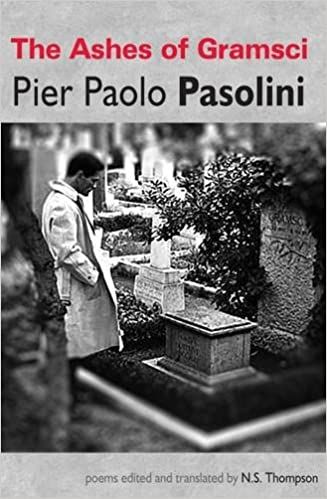

In the poem " The Ashes of Gramsci ", Pasolini imagines a dialogue between himself and the founder of the Italian Communist Party, in which he simultaneously describes his relationship with Gramsci between the same and different emotions. The poem expresses his inner conflict, the most discussed aspect of Pasolini's life and work. The poem of the same name was published in 1957, however Pasolini wrote the poem in 1954, just before the Soviet tanks arrived in Budapest in 1956, a watershed event in Hungary that caused many CCP members and supporters to disagree with the poem. The party broke up.

However, neither in 1956 nor in 1954 did the first signs of tension between Pasolini and the Communist Party appear. In the years after World War II, Pasolini became a political activist in the Friuli region, which borders Yugoslavia, where the communist regime was established. For the first and only time in his life, he was a fully qualified political activist, a respected local leader, and as a party delegate he attended conferences in Paris, Hungary and all over Italy.

However, despite his reputation within the party, he continued to be critical of the party. In 1945, his brother Guido, a partisan, was killed by a communist brigade in the so-called Porzûs massacre, several of which occurred in the final stages of the war. One of the most controversial events. As early as 1948, Pasolini advised his comrades to acknowledge the party's responsibility, but at the same time he strongly condemned those who used his brother's death to fuel right-wing propaganda - including Christian Democrats.

Relations with the Italian Communist Party became extremely strained in 1956, when he published a polemic against orthodox communist intellectuals. After being criticized by him, the reaction of those people was as everyone imagined, but strangely, the most violent attack came from Franco Fortini (Franco Fortini), another non-mainstream thinker not affiliated with the Italian Communist Party , he was also Pasolini's close friend and long-time partner. Instead, at the end of that decade, when the communist cultural community accepted his second novel, A Violent Life , he began to gradually approach the Italian Communist Party.

Between 1960 and 1965, Pasolini wrote a column for the Italian Communist Party's news magazine Vie Nuove . In the column, he interacts with party readers, members or supporters, commenting on a variety of topics, from the social role of intellectuals, to Hungarian literature and the suicide attempt of Brigitte Bardot. This interesting and little-known corpus (especially outside of Italy) was published in 1977 under the title The Beautiful Flags .

Despite this collaboration, Pasolini never became a full-fledged organic intellectual. He is always looking for a different audience. Towards the end of his life, he wrote for Il Corriere della Sera, the main mouthpiece of the Italian bourgeoisie at the time (and now is), with independent journalist Piero Ottone as editor. There, Pasolini wrote the most controversial parts of his life, perhaps because in this neutral (if not unfriendly) place he felt no limits.

Even as his audience grew, the CPCI remained Pasolini's main interlocutor. In June 1975, he announced that he would still vote for the party because it was an "island where critical consciousness has always been desperately defended: human conduct can still retain its original dignity." In his famous late 1974 publication In the article "I Know ", he argues:

The Italian Communist Party is the savior of Italy's poor democracy. The Communist Party of Italy represents the clean state in the dirty state, the honest state in the hypocritical state, the smart state in the stupid state, the educated state in the ignorant state, and the humanitarian state in the consumerist state.

In the last months of his life, Pasolini developed a close relationship with the Rome branch of the Italian Youth Federation of Communists (FGCI), the youth organization of the Italian Communist Party, accepting invitations to public gatherings and even inviting members to their homes .

One of them, Vincenzo Cerami, read Pasolini's speech to the Radical Party convention, which he would have given if he had been alive, The Radical Party is a center-left libertarian force. In that speech, Pasolini re-emphasized his Marxist beliefs, his support for the Italian Communist Party, and his fervent hope for a new generation of Communists.

After his death, Gianni Borgna, another member of the Federation of Young Italian Communists in Rome, gave a speech at the funeral, which was a party business in itself: it started with the House of Culture and then with the Italian Communist Party connect together.

As an unorganized, unorthodox Italian intellectual of the left, Pasolini understood better than many others what role intellectuals could play not only in Italy, but in the rest of the Western world. Marxist intellectuals basically lived in contradiction, he wrote in the first issue of Officina , a cultural and political magazine he founded in 1959. They are communicating with a bourgeoisie who will not listen. This requires intellectuals to become spiritual guides. According to Pasolini, the process was complete by 1968: the left - not to mention the CPCI - no longer had cultural hegemony. Instead, it belongs to the industry. "The intellectual," he wrote, "is the cultural industry that put him there: why and how the market wants him."

1968

In the summer of 1968, Pasolini started a column for the non-left magazine Tempo, in the first article he wrote: "The reader certainly knows I am a communist: but he also knows that I am. Fellow Italians, this relationship does not imply any reciprocal commitment (on the contrary, it is a rather tense relationship, I have as many enemies among the communists as I have among the bourgeoisie).” Article Mention was also made of a small party formed at the time, the Socialist Party of Proletarian Unity - which Pasolini despised for being sectarian - and the Catholic left. But, that same year, another devastating interlocutor was about to appear before Pasolini: the student movement.

Most people think that Pasolini is against the students and for the police, a no-nonsense myth that spreads around the world. A narration in A Film Maker's Life , a 1971 documentary about Pasolini, says: "He sided with the police in a totally surprising and unexpected way. "

The myth began with " The PCI to Young People ," a poem by Pasolini after the Battle of Valle Giulia that marked the beginning of 1968 in Italy. In his usual contradictory style, he wrote that he sided with the police because, unlike the students, they were the sons of the poor. But, just a few lines later, he said, "Obviously we're against the police as an institution." Finally, he couldn't be more clear: "Do I have to consider the possibility of being on your side in a civil war, Put aside my old revolutionary ideas?"

Reading the entire poem and understanding the context helps us understand that Pasolini's view of the student movement is more complex and approving than is commonly assumed. Wu Ming 1, a member of Wu Ming's group, summed it up this way: "After reading all these tirades (full texts, not just four or five extrapolated verses, they were wielded as clubs by the thugs) ), we cannot conclude that Pasolini supported the police."

But critics, especially those on the right, are free to quote famous quotes not only to disparage the writer but to use him for their own benefit - conservatives in Italy and abroad have been criticizing Antonio for decades Gramsci took the same approach.

Pasolini, a fellow communist, not an organic radical (he was nearly 50, after all, how could he be as a leftist of the previous generation?), he did support the emergence of Italians in 1968 and 1969. student movement and other movements. The only two "democratic revolutions" of the Italian people, he said, were the resistance movement and the student movement. He wrote the same in an open letter to Italian Prime Minister Giovanni Leone when police violently crushed protests at the 1968 Venice Film Festival.

He has spoken and written repeatedly against the police, but that doesn't mean he is against the individuals who work for the state's armed forces—usually poor civilian proletarians and peasants. After all, Italy is a place where groups like "Proletari in divisa" (proletariat in uniform) tried to organize the armed forces and gained some influence over the years.

In 1971 Pasolini became director of Lotta Continua magazine, one of the organizations of the Italian left outside parliament after six or eight years, and he financed and helped to film a film about the fascist planning of Piazza Fontana Investigative documentary on the bombing.

It is impossible to understand Pasolini at the time without understanding these relevant contexts. As Wu Ming No. 1 wrote:

If the context is not considered, what is left? Only a few pictures—fireflies, the end of the peasant world, the corpses of hippies—turned into these clichés, innocuous things...these were made by the mainstream culture that persecuted Pasolini, the detractors' press heirs, and Nourished by the political heirs of street attackers.

The New Left

Pasolini's relationship with the non-Italian and non-European leftists deserves a special mention, because the third world - as a place, as a concept - is important to filmmakers. Back in 1961, he referred to Africa as "my only option" and said Bandung was the capital of three-quarters of the world and half of Italy.

Pasolini's take on the American left suggests that he needs to find new ideas, new stimuli, new faces and places, whose importance he sometimes exaggerates. On his first visit to New York in the mid-1960s, he was convinced that the New Left in America "would produce a primitive form of non-Marxist socialism." He wrote: “The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee ( SNCC) , Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and many other movements, which in the midst of chaos cobbled together the New Left in America, Reminds me of the Italian resistance period," and, after visiting the Harlem area, he claimed that "the core of the Third World Revolution struggle is actually very American."

In his famous diatribe against Italian students in 1968, he made it clear that the American movement was an example to follow. We can thus connect Pasolini with the many intellectuals and artists who visited the United States in the second half of the 1960s in search of revolutionary movements, including another important Italian filmmaker, Michelangelo Antonioni ( Michelangelo Antonioni), who shot Zabriskie Point in California. We can also see Pasolini's response to the Haarlem District, part of a controversial and certainly Eurocentric exploration of the Third World that he ran from the late 1960s until his death the main ideological core.

Pasolini's fascination with the American left is worth noting at a time when Italian communists were more focused on the East than the West. A lifelong communist, the poet and essayist was not afraid to go against party lines in search of the most promising revolutionary movements, as he remained open to the contradictions and challenges of the evolving capitalist world.

When we recall his incisive heresy thought, it is enough to make us see Pasolini as part of the fine tradition of the Italian left—with all its contradictions, limitations, divisions, and its ability to inspire and influence the global left.

January 6, 2018

Luca Peretti is a visiting assistant professor at The Ohio State University. His research areas include Italian media, film history and Italian cultural history. He is the author of the book Pier Paolo Pasolini, Framed and Unframed: A Thinker for the Twenty-First Century (2018) 's joint editor.

Original link: https://jacobinmag.com/2018/06/pier-paolo-pasolini-pci-communist-party

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…