如果您對馬克思主義有興趣而想學習或研究,或者可以為翻譯馬克思主義的文章作出貢獻,我們真誠地歡迎您的加入。 網址:https://www.marxists.org/chinese/index.html 臉書:https://www.facebook.com/marxists.internet.archive.chinese

Ukraine's Socialist Heritage

﹝Canada﹞John Paul Himka

Translated by Yi Tianfang, Proofreaded by Handa

Putin-led Russia is waging a litany of destruction of Ukraine's citizens and infrastructure in the name of "denazification". The Russian president and his propaganda machine have been vastly exaggerating the power of Ukraine's neo-fascist leanings, often brazenly lying. So one gets the impression that all movements that develop Ukrainian culture and secure an independent state are tainted by fascism. As a correction to these notions, this article briefly reviews the history of the socialist movement in Ukraine.

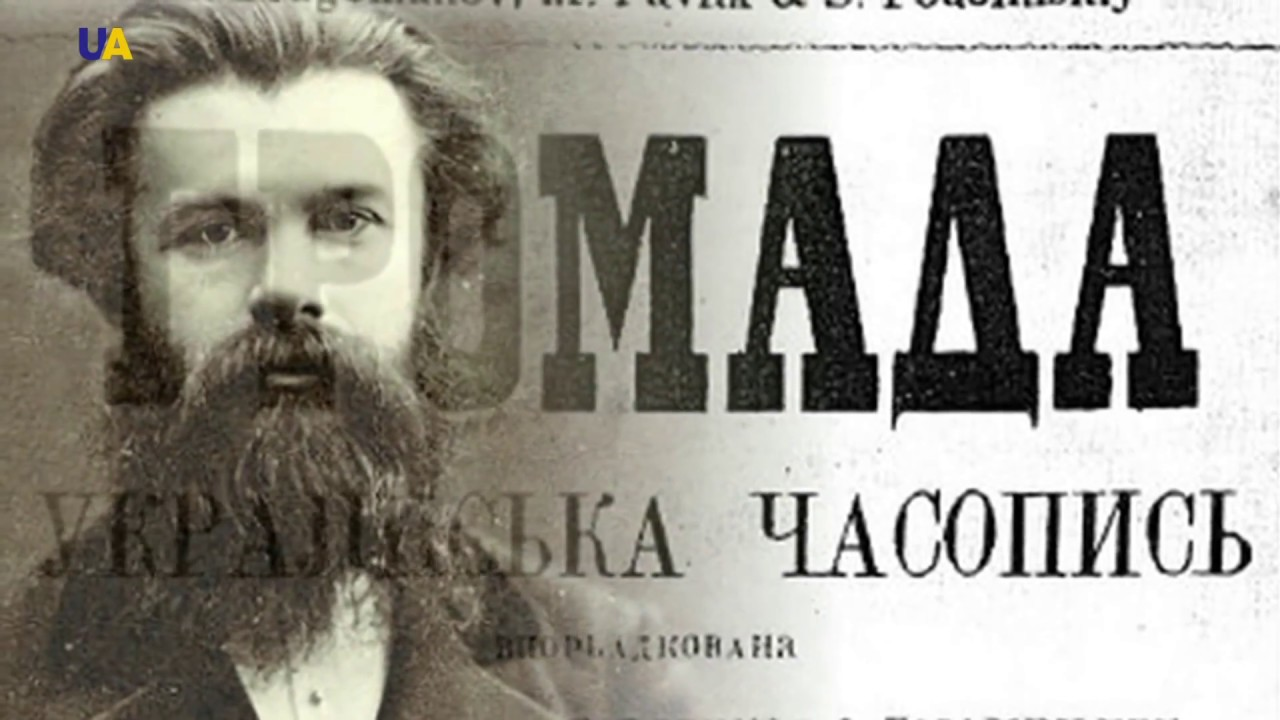

Modern Ukrainian politics was born in Kyiv in the 1860s and 1870s. At that time, the city accommodated people of the same nationality - Russians, Poles, Jews and Ukrainians. The Ukrainians gathered around a group called Hromada, which consisted mainly of students and young intellectuals. The word Hromada means "community" in Ukrainian. The most dynamic leader of the Hromada is Mikhailo Dragomanov, a prominent political thinker and debater. According to his analysis, class and ethnicity on Ukrainian territory tend to be the same. For example: the big landowners are Polish, Russian or Russian-Ukrainian. The craftsmen and merchants were mainly Jews who professed the traditional religion and spoke Yiddish. But the peasants who make up the vast majority of the population in this "granary of Europe" speak Ukrainian and maintain a culture that is very different from other peoples. Thus, Drakhomanov said, the peasants would be the basis of the Ukrainian movement, and those intellectuals educated in Russian or Polish were obliged to learn to write in Ukrainian in order to spread the ideas of enlightenment and progress in the countryside.

Drakhomanov believed in progressive ideals and believed that the whole of Europe was moving towards socialism and, in his view, towards anarchism. In the mid-1870s, when the Russian dictator suppressed the Ukrainian movement, he was forced into exile, first to Switzerland and then to Bulgaria. In Geneva, Drakhomanov published the first Ukrainian socialist journal called Hromada. He preferred Bakunin to Marx, but some of his closest associates disagreed. Sergei Podolinsky actually corresponded with Marx, and Nikolai Zieber wrote a lengthy treatise on Marx's Capital. Draghomanov was also a consistent opponent of early manifestations of Ukrainian nationalism. He himself did not confuse his sympathy for Ukraine with his distaste for other peoples in Ukraine. However, he did oppose the chauvinist tendencies in the Polish and Russian revolutionary movements.

Draghomanov also ignited the socialist movement in Ukrainian territories that were then part of the Habsburg dynasty, particularly in the Galician royal domain in the capital Lviv. Among his Ukrainian students who converted to socialism, the poet, novelist and scholar Ivan Franko is often regarded as the second Ukrainian after the national poet Taras Shevchenko. Two important literary figures. Galician socialists founded the peasant-oriented radical party in 1890. Drakhomanov was a prolific contributor to the party organ, Narod, until his untimely death in 1895 at the age of 53. Before the end of the 1890s, young radicals broke away from their party to form the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party, which represented the easternmost outpost of Austrian Marxism. Activists support a strike by Ukrainian agricultural workers, and the annual May march in Lviv draws huge crowds.

At the turn of the twentieth century, socialist groups known as the "Drakhomanov Circle" emerged in Lviv and other cities, secondary and higher education institutions in western Ukraine. These Drakhomanovs, known to Ukrainians, moved further to the left, eventually joining the Zimmerwald anti-war group during the First World War. They championed the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, the backbone of which would later become the founders of the Communist Party of West Ukraine.

Ukrainians in Kyiv and the rest of the Russian Empire lacked basic civil rights, such as freedom of the press and freedom of assembly and association; in addition, Ukrainian-language publications were severely restricted and Ukrainian-language education was completely banned. But in the 1890s, Ukrainian students began to revive political activity, forming the Revolutionary Party of Ukraine in 1900. The party was rather ideologically immature and split into several parties in 1904, including the Ukrainian Social-Democratic Workers' Party (USDRP) and the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party Spirka (Union. Spirka (Ukrainian Social-Democratic Union). Both parties Both are Marxists, but disagree on ethnicity. The division over how much attention should be paid to ethnicity is a source of chronic tension within the Ukrainian socialist movement. Lev Yurkevych — —USDRP funders, central committee members, and theorists — support positions close to Lenin’s, but argue with him on ethnic issues.

The revolution broke out in 1917, and the Ukrainian Social Revolutionary Party was established in Ukraine. Like the Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party, they were socialists who advocated a peasant revolution rather than a workers' revolution. The Ukrainian Social Democratic Party and the Social Revolutionary Party are the main members of the Ukrainian Revolutionary Parliament Ukrainian Central Rada. The conflict between the Rada and the Bolsheviks broke out in 1917, but some Ukrainian revolutionaries formed pro-Bolshevik groups, namely the Borotbists (the left wing of the Social Revolutionary Party) and the USDRP Independence. After the civil war, most of the Ukrainian territory that belonged to the former Russian Empire was incorporated into Soviet Ukraine. All Ukrainian political parties were banned except the Communist Party of Ukraine (Bolsheviks).

In the 1920s, Ukrainian communism flourished. Galicia, which once belonged to Austria, and Volhynia, which once belonged to the Russian Empire, are now annexed by Poland. Many Ukrainians in Galicia were pro-Soviet in the 1920s, and they followed events in Soviet Ukraine with great interest. While they were discriminated against in Poland, Ukrainian cultural, academic and educational institutions were developing with state support in Soviet Ukraine. Quite a number of Galician-Ukrainian intellectuals made the mistake of moving to Soviet Ukraine for jobs suited to their talents, for example in academic institutions and encyclopedia projects. They were all killed by Stalin's regime in the 1930s. In Volynia, the number of educated Ukrainians dwindled due to the policies of the former Tsar, and even into the 1930s, communism remained a powerful force among the peasantry.

The cultural transformation of Soviet Ukraine in the 1920s was remarkable. During that period, the so-called national communists were developing avant-garde art, literature and theater, and conducting lively scholarship on Ukrainian history and other social sciences. The 1920s was the decade of Ukrainization, a variant of Ukrainian indigenization (korenizatsiia) that was at one time the policy of the entire Soviet Union. Culturally, Soviet Ukraine was basically on its own path, and their interest in what they had achieved never waned.

The Bolshevik Revolution also had a major impact on Ukrainians who emigrated to North America. Pro-Bolshevik journals and organizations proliferated among miners and laborers in Canada and the United States.

Immediately afterwards, a slaughtering darkness descended. The 1930s were a classic Stalinist decade. The Ukrainization policy is officially over. Rapid collectivization led to a terrible famine in 1932-33, the worst of which shifted to Ukraine. Nearly 4 million people in Ukraine died from this famine. Prominent national communists, such as education commissioner Mikola Skripnik and proletarian writer Mikola Herviliovi, were forced to commit suicide. Multiple purges in the 1930s resulted in the imprisonment and execution of nearly all Ukrainian state communist elites.

The horrific events in Soviet Ukraine undoubtedly erased the pro-Sovietism that had existed earlier in Galicia, Poland. There are still socialist parties there, but they are appalled by what they have learned about what is happening on Ukrainian territory bordering the Soviet Union. In the 1930s, a puny left-wing communist/state communist group based in Lviv was able to publish a short-lived journal. In 1939, under the German-Soviet non-aggression pact, the Soviet Union annexed western Ukraine, the Polish territories of Galicia and Volynia. All political parties were dissolved or disbanded on their own, they did not resume their activities under the Nazi occupation (1941-44). The only political group that survived the Soviet and Nazi episodes was the Ukrainian nationalist right-wing group. It draws on the long experience of working with underground conspiracies. However, even before the Soviet Union started arresting nationalists, the NKVD (the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs) hunted down and executed the few dissident communists who remained on the territory of western Ukraine.

Although socialist activity in Ukraine largely stagnated after the 1920s, one prominent Ukrainian socialist survived persecution during the Soviet and Nazi eras, eventually dying in Detroit in 1967. This is Roman Rosdolsky (1898-1967). He turned to socialism as a young man in the Drakhomanov circle in Lviv. He became a member of the Communist Party of West Ukraine and one of the few left-wing communists active in Polish-ruled Galicia in the 1930s. When the Soviet Union occupied Western Ukraine in 1939, he fled to Krakow in German occupation. He was arrested for helping Jews fleeing the ghetto and was imprisoned in Auschwitz. After the war, he moved to Detroit, where he devoted himself to a brilliant interpretation of Marxist economic thought - The Formation of Marx's Capital. This interpretation is based on a comprehensive comparison of Marx's Outline of the Critique of Political Economy and Capital. He also wrote an important book on national issues: "Engels and the 'non-historical' nation." Born in a region where Ukrainian, Polish, German and Russian meet, Rosdolski is passionate about all the classic texts of Marxism, including the writings of Marx and Engels, Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg.

After World War II, there were still some manifestations of Ukrainian socialist thought. Among the immigrants, a group of surviving national communists, as well as left-leaning ex-nationalists, gathered around the Vpered newspaper, published from 1949 to 1959. Among them are some impressive luminaries: Borys Lewytzkyj, a prominent Kremlinist; Vsevolod Holubnychy, political philosopher and economist; ex-Borotbist , the left wing of the Ukrainian Social Revolutionary Party) Ivan Majstrenko. Influenced by the anti-war movement in the United States and the radical politics of the United States and Canada, a group of young Ukrainians in Canada published the Ukrainian-language magazine Diialoh with the slogan "Socialism and Democracy in Independent Ukraine." This magazine has been around since 1977 Years came out and ended in 1987. Members of Diialoh are linked to older members of Vpered.

Socialist ideas also influenced some dissidents who were persecuted in Soviet Ukraine. A notable example is Ivan Dzyuba's 1965 book Internationalism or Russification. This is a critique of post-Stalinist Soviet national policy from a Marxist standpoint, circulated in Ukraine in manuscript form and published only in the West. Leonid Plyushch was a mathematician who was arrested in 1972 for his dissident activities. The Soviet authorities put him in a mental hospital and gave him medicine. In 1976, a massive campaign by Western countries for his release enabled him to move to France. In his memoir, The Carnival of History, he described his captivity and advocated humanitarian Marxism.

There are too many organizations and websites for socialist and labor movements in contemporary Ukraine to even give a brief description here. Fortunately, the Socialist Ukrainian Solidarity Movement in London provides a list of links to the main website: https://ukrainesolidaritycampaign.org/links/ .

March 19, 2022

John Paul Himka is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Alberta in Canada and the author of Socialism in Galicia and Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust Nationalists and the Holocaust ).

Original link: https://ukrainesolidaritycampaign.org/2022/03/19/ukraines-socialist-heritage/

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…