Where are you going: those Mexican wives in Macau|Submission #01

Author: Yuan Yang (sometimes a non-local student who writes drama reviews)

Where did they and them come from?

During Porfirio Díaz's presidency (1880-1910), the Mexican government began to recruit immigrants overseas. At that time, the deserted northern state could not attract European immigrants to build infrastructure, so the government allowed Chinese workers to enter Mexico to work.

From 1919 to 1921, more than 6,000 Chinese workers poured into Mexico, making Sonora in northwestern Mexico the town with the largest concentration of Chinese overseas. Some of these Chinese workers work on farms and construction sites, and some use the Chinese people's economic acumen to sell groceries. By the 1920s, Chinese merchants had even become major U.S. traders in exports to the West Coast of Mexico.

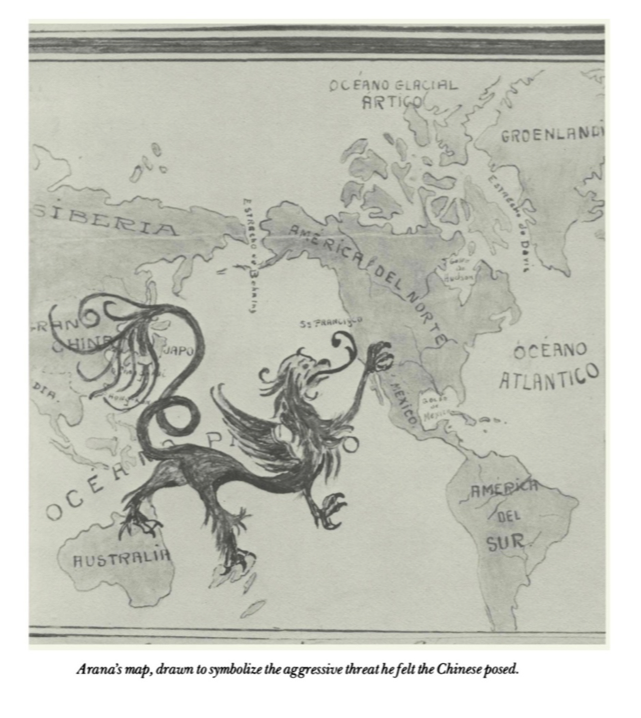

Due to the fact that the Chinese were too prominent in the business circles in northern Mexico and the large number of people living together, the folks planned an anti-China movement in the early 20th century. Although it was not completely successful, it still planted a knot for the Mexicans.

In 1929, the Great Depression in the United States spread to the South, and this Great Depression not only hit Chinese businesses hard, but at the same time, anti-Chinese sentiment among the people was rekindled. The locals feel that the Chinese are a threat to the local economy, and even feel that they are taking their jobs.

As a result, the anti-Chinese state governor Francisco Elías launched a second anti-China campaign to restrict Chinese trade and jobs.

After the anti-China movement in the 1930s, there was a cliff-like decline in the Chinese population in Mexico. For example, the number of Chinese in Sonora decreased from 3,571 to 92, while the number of Chinese in Sinaloa decreased from 2,123 to 165.

According to records, between mid-1931 and early 1934, at least 500 families fled to the United States and were later repatriated to China from San Francisco by the U.S. government. Others returned to their hometowns in China with their Mexican wives and mixed-race children.

For men, it was returning home; for Mexican women, it was exile without a return date.

Rosa Murillo de Chan returned to Canton with her Chinese husband in 1930 with her children, only to find that her husband was not single as he had promised, and that she was a complete outsider in the family. In addition to the logical exclusion, from the legal point of view, Chinese law only recognizes the first legal wife. The Mexican government in their home country also stripped these women of their nationality because of their intermarriage with the Chinese.

Therefore, from the moment she arrived in Chinese territory, she was no longer Mexican, and could not be a real Chinese due to cultural barriers and legal restrictions. The women lost their financial resources and citizenship, and their husbands were no longer the caring lover. They even claimed that she was a maid brought back from a foreign country. Facing the legal long-house wife at home, they had to keep a low profile.

María Pérez was kidnapped and deceived by her husband and brought back to her country. He said the family went on vacation, but when disembarking, her husband took her passport.

Regardless, these women have always had a dream, a dream of returning to Mexico.

However, the Mexican government has refused entry to women who still hold legal status, not to mention those from the lower middle class, on the grounds that they have not returned to Mexico for five years. Dollar).

Chinese-Mexican community in Hong Kong and Macau

After these Chinese and Mexican families returned to China, some chose to settle in Nanjing and Shanghai, while the rest chose to continue living in Macau and Hong Kong. In Macau, the families gradually formed a mutually supportive Sino-Mexican community. This Chinese-Mexican community is mainly composed of Mexican women and some Chinese men. They are in East Asia and their hearts are in America.

According to Alfonso Wong Campoy, there are frequent gatherings of Mexican Chinese and Latin Americans between Hong Kong and Macau. They will go to Hong Kong to watch a football match of the Mexican team, a performance of a national singer, and even organize an organization Dance party, sip on tequila—the soul of Mexico.

Compared with Hong Kong, a British colony, Macau is more culturally close. Portugal has the same roots as the Spanish colonists in Mexico, and is also influenced by the culture from the Iberian Peninsula; the official language of Macau is Portuguese, and there is also the Macanese language formed by the interweaving of different cultures.

Because of its cultural diversity and tolerance of different races, Macau has become their destination, allowing them to maintain their uniqueness as Mexicans among different ethnic groups, without being subjected to mixed-race identity. exclusion. The social ties and friendships formed in Hong Kong and Macau in the 1930s enabled this group of expatriates to continue to support them when they returned to China three decades later.

More importantly, the Catholic Church in Hong Kong and Macau provided the glue of the Mexican community. In addition to allowing them to maintain their faith traditions, the church also provides venues for their gatherings and maintains contact with the Mexican side through foreign missionaries and other clergy to help them return home as soon as possible.

What's more, the Macau Catholic Church allows Mexican women to work as domestic helpers in churches and other institutions to subsidize their livelihoods. Emotional support, financial aid, and even job opportunities are key functions performed by the Catholic Church.

In addition to the Sino-Mexican community in Macau, the Latin American Association of Hong Kong, founded by Manuel León Figueroa, is a social, political, A religious club designed to uphold the unique beliefs of Mexico. The Church of Santa Teresa in Hong Kong still houses the Virgin of Guadalupe dedicated to the Mexican community, who will gather on December 12 to celebrate Mexico's most important religious festival, the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

When it comes to the education of their children, these Chinese and Mexican families are also more inclined to preserve the cultural traditions of Mexico: they insist on speaking Spanish, tell them about their life in Mexico, teach them to love another land far away, and tell them We are Mexicans, but separated by the turbulent times - their parents believe that the anti-China movement is dominated by the Mexican government, and Mexicans in general are not hostile to their interracial compatriots.

long way home

It was not until Lázaro Cárdenas del Río, the 51st president of Mexico, took office in 1934, that the anti-Chinese ethos of the previous government was changed.

When the Sino-Japanese war was on the verge of breaking out in 1937, Mexican aristocrat Eduardo Miller wrote to the authorities, explaining the plight of Mexican women "living on the streets and starving" in China, and urging the government to take measures as soon as possible to save them. citizen.

The authorities immediately set up the Mexican National Repatriation Commission, the first time the state has come forward to provide assistance to Mexican women and their children living in China. The Mexican government remitted 94,000 pesos to the Mexican consulate in Yokohama to support the return of about 400 Mexican women and hundreds of mixed-race children.

But this time, the Cardenas Repatriation only allows Mexican citizens to return, and their husbands are excluded from the relief policy.

In March 1937, the first 89 women and hundreds of children departed from Hong Kong by steamship to the Port of Manzanillo in western Mexico, with continued support from the local communities in Sonora and Sinaloa life after returning home. In 1937-1938, more than two hundred families returned to Mexico in the same way.

Regrettably, the news was slow in those days, and many Mexican women living in Guangdong townships were not informed of the news of their return to China as soon as possible, or they chose not to return to China because they wanted to stay with their families.

When Juana Trujillo Viuda de Chiu's Chinese husband died in 1940 and the family fell into poverty, her relatives wrote to the government, hoping to bring her back, but the government informed her that the budget had already been Running back in action. It wasn't until decades after the end of World War II that the Chinese and Mexican families finally returned to Mexico.

So, will there be a better life after returning to Mexico?

Although the new government tries to help return families reintegrate into society through aid policies, the anti-China sentiment rooted in the people cannot be eliminated in a short period of time.

Rosa Murillo de Chan wrote to President Cardenas, asking the government to help her daughter, Graciela Chan Murillo, get a job in the library; Residents are regarded as foreigners and have not yet obtained their due citizenship rights.

Epilogue

Against the background of transnational marriages and anti-Chinese sentiments, Mexican women who followed their husbands to China were just another group of strangers in turbulent times. They insist on their "Mexican" identity, as the only spiritual sustenance in this language-barrier and culturally-separated country, hoping to return to their homeland one day.

But returning to their homeland, does it mean that they can realize the life they imagined? This is yet another story yet to be told.

In addition, here is a small preview of Ramón Lay Mazo, a key figure in helping Mexican women return to their motherland. His ancestral home is Taishan but he is Mexican :-D He has made great contributions to the continuous communication with the embassy in Manila, Mexico during the return home operation after World War II.

Citations

Camacho, JMS, 2009. Crossing Boundaries, Claiming a Homeland: The Mexican Chinese Transpacific Journey to Becoming Mexican, 1930s––1960s. Pacific Historical Review 78, 545–577.

Camacho, JMS (2012). Chinese Mexicans: Transpacific Migration and the Search for a Homeland, 1910-1960. Univ of North Carolina Press.

Hu-DeHart, E. (1980). Immigrants to a developing society: The Chinese in Northern Mexico, 1875–1932. The Journal of Arizona History, 21(3), 275-312.

#Number of articles: 9️⃣4️⃣

💬 Stories of [Telling Stories on the Frontier of the Empire] |📁Article List |👍Facebook Page |📣 Call for Papers

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!