Facing the crisis in Xinjiang, what can an ordinary person do in 2020?

Facing the crisis in Xinjiang, when we ask "What can I do?", what are we asking?

The problem breaks down into two factors: We think we have a duty to do something, but we don't know what to do

Are we responsible for walking in history? I think there is. But in general, if you think you are not responsible, I have no objection. Whether the "responsibility" here is the specific Xinjiang crisis itself, or the broader responsibility for history. You think no, then you think no, I'm totally okay with it.

If you think you have no responsibility, but at the same time don't want us to suffer from the moral high ground, you have to make a mockery... I have no objection. It's 2020, so enjoy yourself, really.

The entire discussion that follows is by default directed at individuals who feel responsible.

So why don't we know what to do?

One of the important factors is that most users of Simplified Chinese have learned helplessness in politics. Our memories of civil disobedience (if any) are Tiananmen Square, "nail houses", "watching to change China" and "there is always a force that makes us burst into tears". Now all these experiences are far away in the dust of history, and in the present moment it seems that only "this road does not work" is written all over them.

At the same time, the situation in Xinjiang is so extremely bad, we don't know, or in fact, no one knows how it will all end. Expectations for the future are completely vague, if not extremely pessimistic, and thus cannot serve as a guide for immediate action.

However, it is not necessary to have the expectation of what can be done before you can do things. The act of blocking tanks on Chang'an Avenue will not lose its meaning just because it was not stopped in the end. All the things I do now, I do not care about the future. Because if I had to ask, I wouldn't have the strength to do anything.

Don't ask about the future, focus on the present, this is my attitude. With this attitude, there will be more things that can be done.

That said, my first request to you is, stay in this with us.

I really hate the current formulation: "back to normal", like, hell no.

The normality that the world has tried to hold on to since it witnessed and pretended not to have witnessed the Tiananmen incident in 1989 is the cause of all the absurdity we are facing now.

We don't have a normal world to go back to. Speaking of which, where do you plan to go back? make the world normal again Where do you want to go back? By 2018, the moment when the concentration camp buildings can be seen on satellite images but completely denied by Chinese officials? When Foxconn workers jump off buildings one after another but people still go to the Apple store and line up all night to buy iPhones? By the time the 2008 Olympic Games' Big Footprint fireworks explode over Tiananmen Square?

Don't go back, don't expect to go back to the "normal life" you had before you knew all this. You have to move forward with us, don't forget this moment, don't leave this moment behind.

This is the first thing I want to say, this is the premise that I can face all this and barely maintain sanity.

The next very important factor is that you cannot escape.

You want the world to be hopeful, you want to make sense, and you want the world to behave in a way that ultimately conforms to your basic imagination: good and evil are rewarded, justice comes late, and so on.

But you can't see that right now, you can only see the absurdity, seeing those things happening brightly in the sun.

Please don't hide, don't take your gaze away, even if the absurdity itself is glaring and painful, you can't avoid it.

Being stung by absurdity is your most basic moral obligation as an ordinary person living in 2020.

That being the case, let me recommend some of the blatant absurdity itself for a straight look.

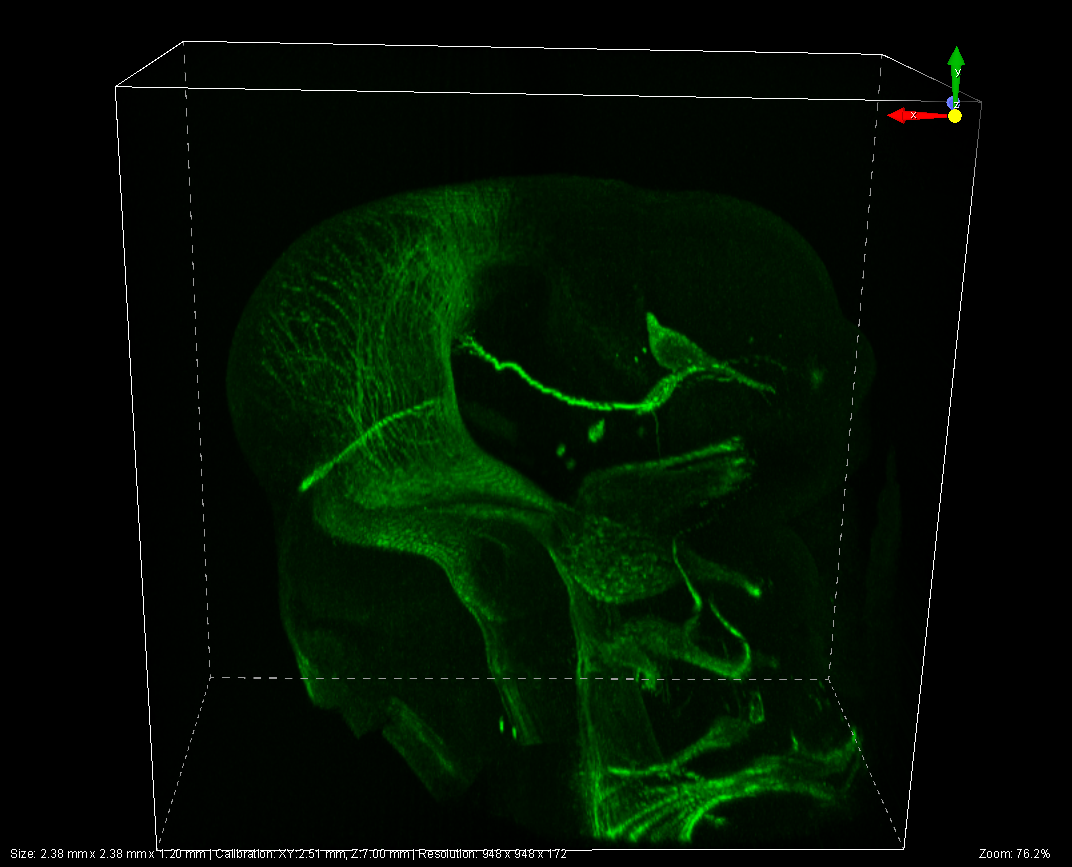

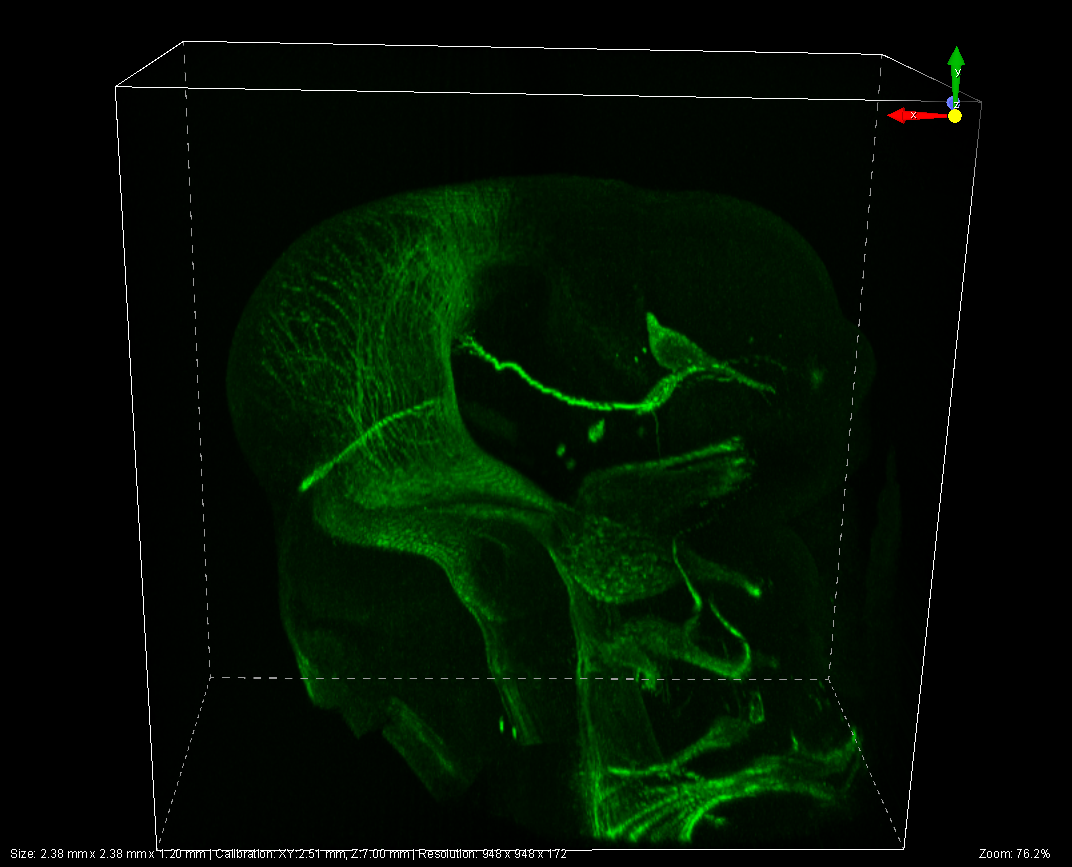

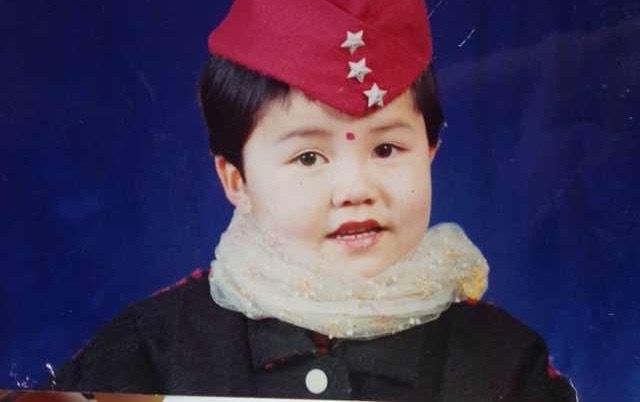

First of all, I recommend my story written by @satopol .

This article actually uses my family's affairs and tells the history of Xinjiang since 1949 from a local perspective. In this regard, it is very suitable for readers who are completely out of the situation to quickly absorb the necessary background knowledge.

At the same time, my story can be regarded as interesting enough. There are so many elements that I can’t make it up: the first group of my peers went to a Chinese school, was bullied all the way to be admitted to Peking University, and made a fuss about marrying a Han husband... Then in the concentration camp years, parents followed each other. Disappeared, commanded his younger sister to flee to the United States remotely, found her parents almost by accident, and turned against her mother because she continued to speak out...

After I finished speaking, I felt magnificent, and it was really easy to read. In addition, Sarah's other stories are also very easy to read, such as the one about the Rohingya "private-run teachers" . After reading it, you will feel that the protagonist is a friend who has known each other for a long time and gradually lost contact but still cares about her. I can imagine myself occupying a similar place in the minds of many who read my story: a friend who was once familiar, close, and still cares.

Then I recommend the works of Darren Byler, and the monthly column in Sup China is very good to read. His writing style is gentle and restrained, presenting real people as if they were around you and could smell the tobacco on the poet's fingertips.

In general, I hope that the articles you read can make you feel that we are concrete and real people who can walk by your side, not some (many times literally) vague-faced believers and victims .

In terms of books, I can’t push out many books at the moment, because I don’t read much. For now, you can read "A Tibetan Revolutionary" and "My Liangshan Brothers", both of which have good Chinese and English versions. These two books are very helpful and can give you a pretty good understanding of the situation of non-Han people in China today.

I mean, it's 2020! How special are Uighurs? Of course there is, but it can also be said that there is no. I hope that everyone who pays attention to the situation of the victims of the Xinjiang crisis can also pay attention to the situation of other victims under the CCP. After all, the perpetrator is the same, and everyone's stories are connected, all connected.

Then I have another one that might be counted as a favor.

I don't force this point, you don't need to accept it, you see I suddenly started using "you" again.

What I want you to understand, and what I want you to try to understand and accept, is that we, the CCP victim community, as a whole, are a fucked up group of people.

If you need a set of clean and beautiful perfect victims, we can actually provide a few because of our large base. But in general, of course, there are still many people who are not perfect.

Don't give up on us just because we are not perfect. Don't give up on us just because some of us support Trump (I know it's hard to justify...but still). Don't give up on us just because some of us are trying to spread or even outright make up fake news.

Ugh.

In general, please believe that we are all in this together. Don't treat yourself as an outsider, don't treat us as an outsider. This is my request.

For now, if you are filled with righteous indignation and you must do something to strengthen externalities to relieve your hatred, I also have a little suggestion.

First of all, it is simple and rude to vote with money, very good! And it's cool, please give it a try.

Right now, the only person I can passionately recommend with my personal reputation as a guarantee is Xinjiang Victims Database . I knew Gene Bunin before this round of Xinjiang crisis. At that time, his most well-known works were a series of articles about Uyghur restaurants in the Mainland. Now his name is closely associated with the "Xinjiang Victim Database".

The database recently counted more than ten thousand victims, two of whom were my parents.

If a million people, or 10,000 people, sound like too many numbers to make you feel, the information presented in this database will sting you with cold detail and specificity. (The website is a bit slow to access however, so please go to GoFundMe and send them money !)

If it is convenient, it is also good to support Uyghur businesses such as restaurants, anyway, they are generally delicious. But I do not recommend traveling to Xinjiang. Of course, the plague has sealed everything up now, but even if there is no reason for the closure of the city due to the plague, I still do not recommend traveling to Xinjiang.

And then just, use your voice.

When Reiza was bullied by the Internet last year, Zumret wrote this paragraph on Weibo:

If you like a star, blogger, painter, or author, you should say it. Don't think that if the other party has a lot of followers, it's not bad for you to say rainbow fart. Poor. Just miss you. If you keep blowing this sentence, disheartened authors will be motivated to continue writing, celebrities who are scolded and crying will have an extra smile, and bloggers who haven’t updated for a long time will also be encouraged. Don't like silently, because people who hate them don't silently hate.

It still applies to the current situation. You don't have to write a heartfelt confession that goes all the way from the extreme left to the extreme right. All we want is to be seen, because we have been invisible for too long, and because being seen can actually improve the situation of at least individual victims. So you just have to say, I saw it, I watched it, and that's good enough.

Will we meet where there is no darkness? I don't know, and honestly I don't really care. I only care about today and the moment, we see each other's fireflies from afar, see each other.

Thanks for reading this far.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!