188 | In memory of Arendt | We must think (Part 1)

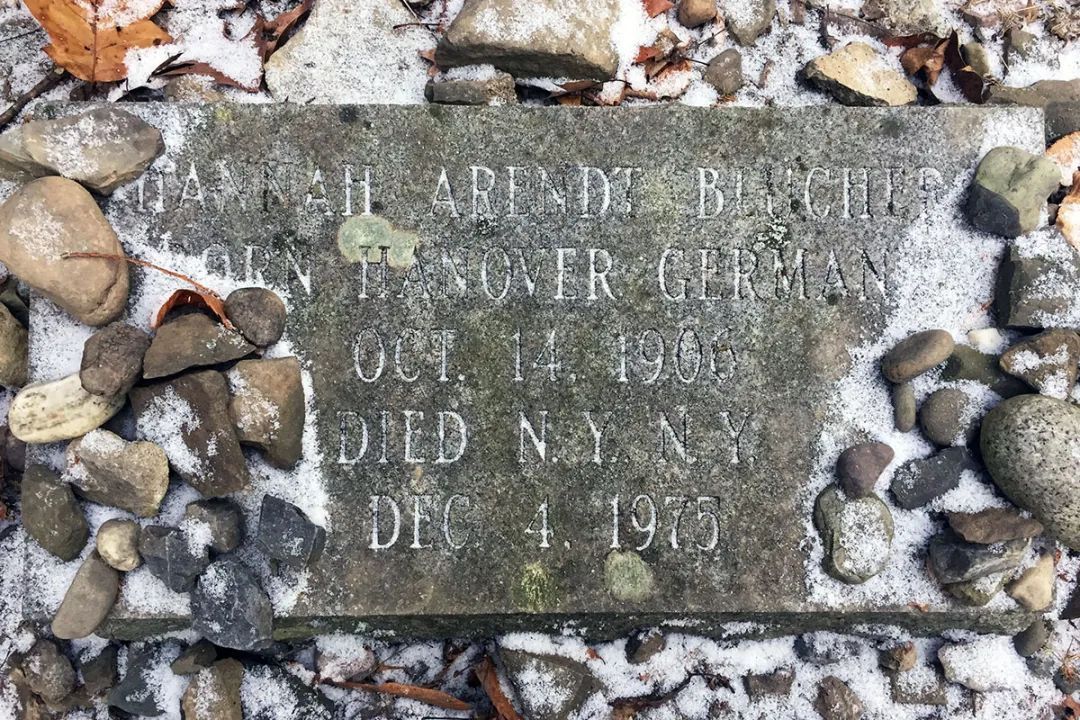

On the evening of December 4, 1975, Hannah Arendt suffered a heart attack while entertaining friends at her apartment and died on the spot. This seems to confirm her own almost prophetic writing in " Understanding and Politics ": "Everything in the world is changing, just like our lives. In the face of reality, our deepest fears and best hopes cannot help us in the face of impermanence. The world is fully prepared." However, if we think along Arendt's logic, then death may also be another kind of rebirth, and the newness in it can only be continuously released in the interpretation of future generations.

In the post-Ahrendt era, we are undoubtedly re-understanding Arendt. The author of this article, Jenny Turner, is a long-term contributor to the "London Review of Books", focusing on topics such as feminism and intellectual history for a long time. In the article, she sorts out Arendt's growth experience for us, and connects her life, thoughts, emotions and other experiences through her works in different periods, and the editor does not repeat them in the notes.

It is worth mentioning that Turner tried to re-understand Arendt from the perspective of feminism. Turner reinterprets Arendt as a "marginal female thinker". And she also mentioned that the contemporary author Gillian Rose, also in her 1992 work "Broken Intermediary", regards Varnhagen, Luxembourg, and Arendt as three marginal female thinkers with core positions .

In contrast, Arendt herself rarely dealt with feminist-related topics in depth during her lifetime (the only short essay that directly addressed women's issues was published in 1933, entitled "On the Emancipation of Women"). In a speech at Yale University in 1968, Arendt said publicly, "I don't think about being a female professor at all, because I have long been accustomed to being a woman." In the same year, Yale College just enrolled the first A group of female students; in 1975, the year of Arendt's death, she remained Princeton's only female full-time professor.

Why is a highly educated female thinker who is constantly exploring the boundaries of philosophy and politics so resistant to responding to gender-related issues? What does it mean to be "accustomed" to being a woman? For us today, how can a feminist perspective help us understand Arendt's works, thoughts and life from different dimensions? Revisiting Arendt's life, it is not difficult to find that those female dimensions that she called "accustomed" have subtly affected her life trajectory. When she was not yet eighteen years old, she fell into a relationship with a philosophy professor who was twice her age. During her studies, she changed universities and finally completed her studies. Her first book focused on a Jewish intellectual woman — a woman named Varnhagen who did not publish anything during her lifetime. In the middle and later stages of her life, she supported each other with different female assistants, editors and friends, and her last work was compiled and published by a female friend... Even though Arendt did not give an answer during her lifetime, her story is still being told to future generations inspired. (For more on this, see also Hannah Arendt: A Woman in a Dark Age and Identity and Revolt: Hannah Arendt and Her Jewish Salon Mistress in Eastern Historical Review )

Regarding how history is reflected and reconstructed, Arendt himself may have been prepared: "every event in human history is an unexpected revelation." Although historians "the story has a beginning and an end, but the story It takes place within a larger framework, that is, history itself, and history is a story with many beginnings but no end." There are many similar stories, and friends who are interested in Arendt's life and thoughts may wish to read Participate in the thinking process together in the message area.

Original Author / Jenny Turner

Original link / https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v43/n21/jenny-turner/we-must-think

Original release time / November 4, 2021 Translator / Proofread by He Xiaofeng / Edited & input by Meng Zhu, Zihao, Ye Wei, Wang Jing / Wang Jing

Arendt on twitter

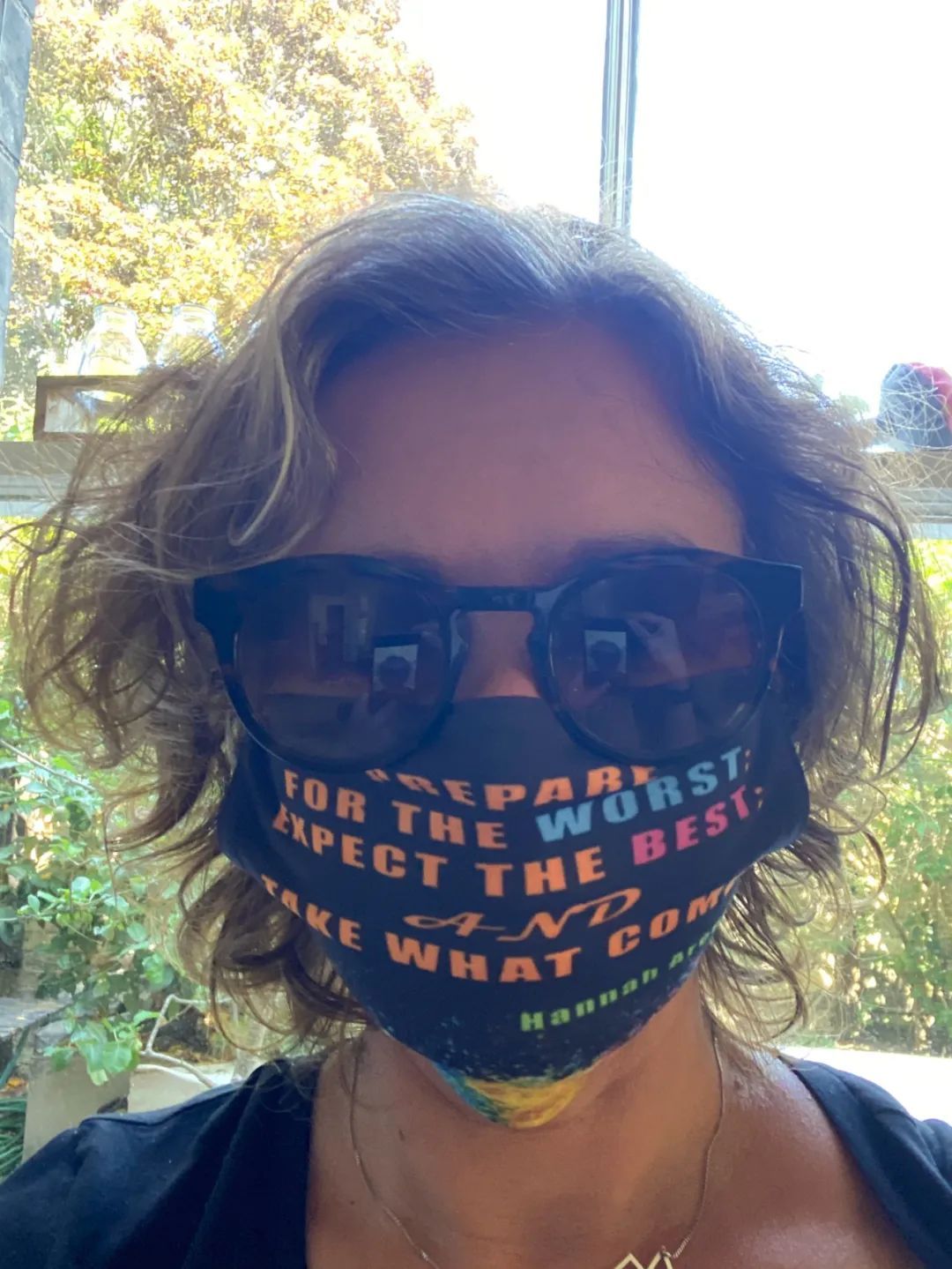

On June 23, 2020, Lindsay Stonebridge, a humanitarian and human rights expert at the University of Birmingham, tweeted a selfie, wearing a face mask, which read:

prepare for the worst

hope for the best

meet what's coming

— Hannah Arendt

A few hours later, across the Atlantic, Samantha Hill, then assistant director of the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College in New York State, commented below, "That sentence did not come from Arendt :/ ". Stonebridge replied, "I know, but I think we should speak out."

Hill suggests that we might as well quote this quote from Arendt: "We don't always need to speak". It comes from Arendt's 1964 interview with Günter Gauss. Hill tweeted many quotes from Arendt, including "writing is part of the process of understanding," "speech is a mode of action," and "evil comes from the inability to think." She also tweeted a photo of the Arendt manuscripts from the Arendt collection. And the collection, in the words of Arendt's former student and first biographer Elisabeth Jan Breuer, "Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Goethe, Rilke" and so on, is Arendt's old friend. Hill said in "A Review of Arendt", "We can see Arendt standing at her wooden desk, standing next to the blue typewriter, holding silver scissors and Scotch tape, Treat pictures like words and try to understand them".

I referenced Arendt too - I tweeted a tile, not a mask - and I tweeted a picture linking it to Arendt. In Aberdeen, May 1974, Arendt posed for a photo with her close friend Mary McCarthy. That place is less than a mile from my college. What were they two doing in Scotland? Arendt was delivering the second part of the Gifford Lectures (later to become The Life of the Mind) when she had a heart attack on the way to the podium. McCarthy arrived from Paris to help, and later Arendt's longtime assistant, Lotte Kohler, also arrived from New York. When Arendt died the following year after a second heart attack, McCarthy and Kohler became her executors.

Arendt cult is a mystery

Walter Lacker lamented in 1990, "What an enigma the Arendt cult is". Before him, Isaiah Berlin and Han Puxia also lamented in this way. Such a person who "has no originality, depth, and system" has attracted much attention. Raquel wonders, is it because women like to read about women? Because women like to read about women, why did Arendt, who was "extremely emotional, deeply influenced by impressionism, romanticism, and metaphysics," appreciate the "unpopular" Luxembourg? At present, the reason why scholars are paying more and more attention to the practice of mutual citation among women may be as Lacker said. Yes, women do like to read about women and want recognition for their work.

But, as David Runciman argues on his podcast Talking Politics, this phenomenon also had something to do with Arendt's ill-fated fate. That’s why Ken Krimstein’s 2018 graphic novel is called Three Escapes from Arendt. Arendt did not arrive in the United States until 1941.

Before that, she had escaped various Nazis several times. The first escape—in the 1920s, when Arendt was a child—was from a possessive, soon-to-be-Nazi boyfriend. The second was escaping from a Gestapo cell in the 1930s. The third was escaping Güle concentration camp before the German occupation of France. Arendt was one of the few prisoners who seized the moment of France's surrender to escape, leaving "with nothing but a toothbrush". They understand what happened to those who couldn't escape, and they live with that understanding for the rest of their lives.

The irony of the quote on Stonebridge’s mask is that Arendt didn’t “greet what’s coming.” Jan Breuer said in "The Biography of Arendt", "Some friends think that Arendt is a person who embraces conspiracy theories too much", although these friends are glad that they have listened to Arendt's conspiracy theory. Arendt said in "Eichmann in Jerusalem", "Once a precedent is set and recorded in history, this matter will remain hidden in human thinking for a long time. This is the character of human affairs. There is no Punishment has sufficient deterrent power to deter crime, but on the contrary, whatever the punishment, once a particular crime has been committed once, the chances of its recurrence are far greater than the chance of its first occurrence.” Compared with the destructive potential of technological developments after World War II, "Hitler's poison gas equipment can only be regarded as toys in the hands of naughty children."

Was Arendt a prophetess? Or a brilliant fortune teller?

During Trump's term of office, Arendt's citation was particularly eye-catching in the American media's song and dance. Is the Trump administration totalitarian? Is Trump a fascist? We can quote from "The Origins of Totalitarianism", "No matter how much we learn from past history, we cannot predict the future".

In any case, Trump is not a totalitarian, as Rebecca Panovka said in Harper's magazine, the problem is the word total. She believes that "Trump has never really made a totalitarian move to subjugate reality to his fictional world". As Panovka said, the so-called "alternative facts" did not start with Trump. One reason Trump's lies have been so successful is his ability to exploit a lack of public trust. Arendt said in "Truth and Politics", "As far as I know, no one has ever regarded sincerity as a political virtue." In Lies in Politics, Arendt discusses the Pentagon Papers and the "alternative facts" it presents about the Vietnam War.

Although Arendt's writings on America are widely read and discussed, many of her ideas are alien. She arrived in the United States at the age of 35 and spent most of her time with German immigrant intellectuals (American Jews found "Eichmann in Jerusalem" offensive because it directly showed the arrogance of German Jews towards other Jews) and American leftist elites. Together.

To use an analogy, "On the Revolution" shows the strange contrast between the French Revolution and the American Revolution. The French Revolution was bad because "the existence of poverty" inspired it, drove it forward, and ultimately killed it. The American Revolution was a good thing because "wretched and humble suffering pervaded everywhere in the form of slavery and Negro labor," but it didn't stop the founding fathers from crafting the Constitution. Arendt dedicated her life to keeping "social issues" out of politics.

In "Reflections on Little Rock," "The Prideful Lady"—as Arendt's opponents sometimes called her—glances at Elizabeth Eckford's famous photograph of a black girl alone On her way to school, a group of hateful white men yelled at her. But Arendt sees only "her absent father, and "the equally absent NAACP representatives," and writes, "Have we reached the point where we want children to change or improve the world?" the point? Are we going to let this political war be fought on campus? "

Until the 1970s, academic colleagues still regarded Arendt as "a journalist, not a philosopher", a media personality from Central Europe, and a more intellectual Ayn Rand. Undoubtedly, Arendt's best-known works were published in magazines rather than academic journals, and they were "Anglicized": in The New Yorker, "Eichmann in Jerusalem," an ad for a super mask, a Cartier Advertisements for diamond hairpins, Tomlinson chairs, and RCA's ad were all set together, no doubt odd.

But there was something even stranger than that. On November 18, 1945, Arendt wrote to Karl Jaspers, "For the past 12 years, a quiet academic life has been a luxury for me. I have become a freelance writer. between historians and political journalists". But the year before, in 1944, she had just published her first article in Partisan Review, on Kafka [School Note: "Re-criticism of Franz Kafka"].

Exile · Friendship · Thinking

Did Arendt care about the reception of her work, and whether it was well received or not?

Political theorist Margaret Canofan said in Arendt's Political Thought Reinterpreted that "her most famous works are essentially introspective". Kanofan believes that "the motivation behind her writings is her own desire to understand, and writing is part of the understanding process... She is basically indifferent to all kinds of misinterpretations of her writings." In Kanofan's view, the way Arendt shaped her "trajectories of thought" was not haphazard or sloppy, but neither was it painstaking.

According to Canovan, Arendt's work is "a part of the sediment left over from an endless process of thinking and writing, which made her famous, like islands rising from continents of thought mostly submerged in seawater" . Even Arendt's most famous and well-established work, many of its arguments are clouded by side details: "Her writings are like medieval manuscripts, where dragons and griffins dance on letters, and leaves and vines twine In words: a jeweled work of art, but one that is easily distracting."

McCarthy wrote to Arendt on April 26, 1951, "I have read "The Origins of Totalitarianism" and for the past two weeks have been completely absorbed by it, whether in the bathtub or in the car. ". Over lunch after lunch, amid small talk about politics, sex, Norman Mailer, and gift exchanges, McCarthy and Arendt's letters developed into a genuine friendship.

When friends and foes alike accused Eichmann in Jerusalem, McCarthy defended her. She argues, "Frankly, I love Eichmann, and I hear an ode in it—not a totalitarian one, but a transcendental one, a heavenly one, like Figaro." or the final chorus of the Messiah." And McCarthy, in her 1963 feminist-archetypal bestseller "They," flirts playfully, at the end of which the charming Leckie carries the Baron Mrs. runs off into the sunset, and the other girls worry that "Leggie's looking down on them because they're not gay."

Finally, after Arendt's death, McCarthy was responsible for editing and translating her last posthumous work, Life of the Mind. McCarthy said in "Postscript", "She was dissatisfied with the English language and its daunting and mysterious limitations, although she had a gift for languages, as if she could express in Sioux or Sanskrit as fluently, forcefully, and sensitively. , but her sentences are long German sentences".

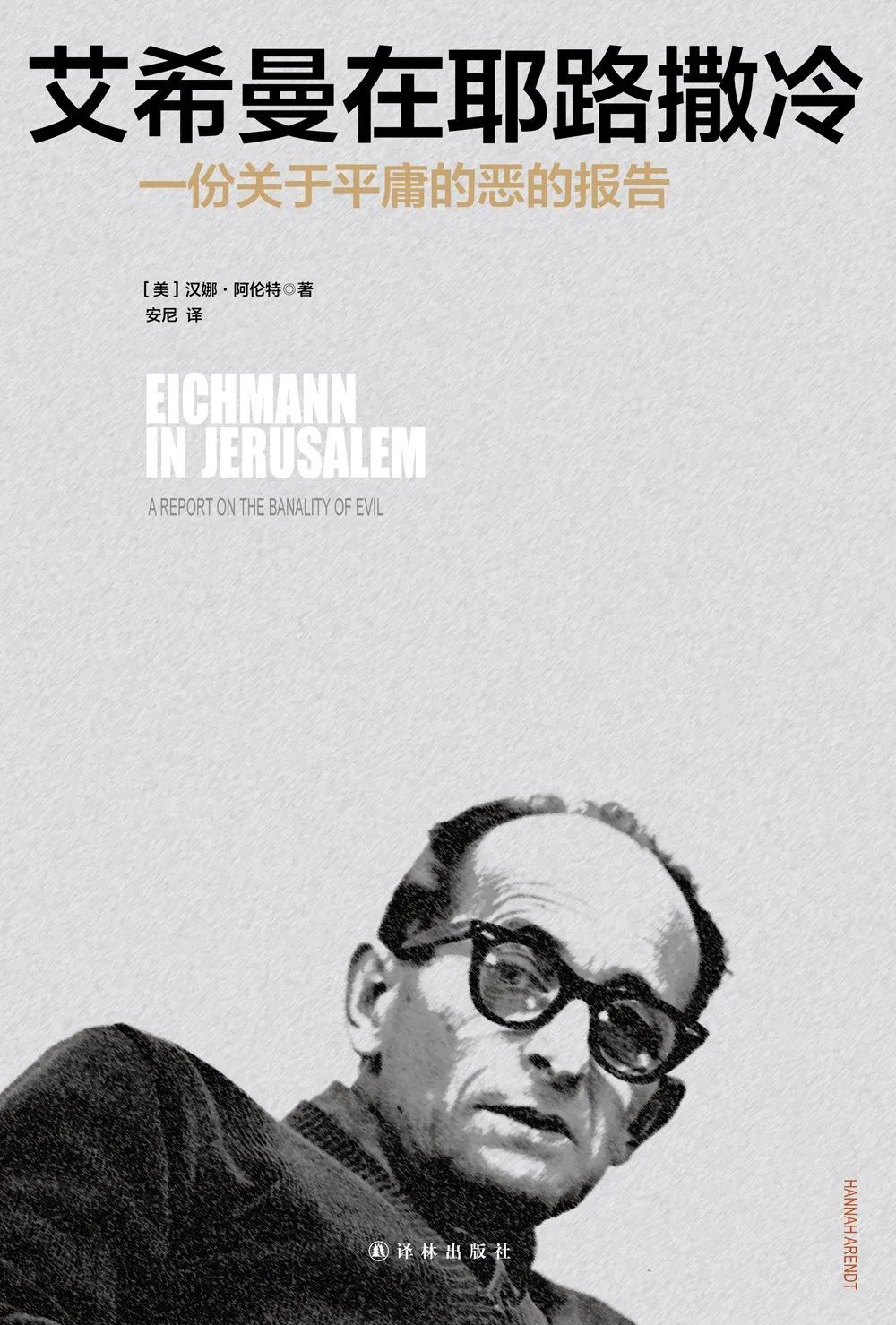

Chinese translation of "Eichmann in Jerusalem", translated by Anni, Yilin Publishing House

For example, when "Eichmann in Jerusalem" was published with the subtitle "Banality of Evil", it was stated that lies, sloppiness, technology, and logistics "are the main culprits of disaster and havoc, far more than all the inherent evils of human beings." The sum of natures is more terrible." And yet, that phrase was on the cover of a book about the Holocaust in the 1960s? Perhaps, this is not the best way to elicit a calm and rational response.

"Banality of evil" isn't the only gaudy claim in "Eichmann in Jerusalem." The problem with this pompous claim is that it mixes cool, no-nonsense reporting with odd sarcasm. The defendant was like a puppet in a puppet show, with "not very regular teeth, and a thin neck stretched from head to tail." The court's German translation is "a joke". "The joke lies in Eichmann's heroic struggle against the German language, and it is often Eichmann who loses." Eichmann referred to "like pulling out teeth" and "absolute obedience like a corpse".

Although McCarthy was quick to regret the tropes of Figaro and Messiah, Arendt thinks McCarthy is right: "You are the only reader who understands the joy with which I have written this book. Since then Now, I feel very light about the whole thing -- twenty years later --," says Hill, "the irony creates a sense of distance and exposes the logical absurdity with a sense of humor." "Like someone who writes in a satirical tone, when she gets involved in an argument, her words are extremely cutting, which escalates the discussion from mere statement to sarcasm," said Jan-Breuer.

Arendt said Eichmann in Jerusalem was "delayed therapy". She told McCarthy, "From then to now, I feel very relaxed about the whole thing - twenty years later. Don't tell anyone, or it will be evidence that I have no heart." Perhaps, she left the heavy past on the library in Berlin, the Gühl concentration camp, and the ship across the Atlantic. Kohler described Arendt in the United States as "strangeness, homelessness, and loneliness are the characteristics of Arendt's life."

The only person who "speaks the same language" is her husband Blücher. Arendt remained loyal to him and remained so after his death in 1970. The old friend and poet Randall Jagel said in "Scenes from the Academy", "Even Constance saw that, to some extent, the life of the Rosenbaums was over." The author himself assumes the role of Constance, while Gottfried Rosenbaum and Irina Rosenbaum refer to Lücher and Arendt, respectively. The novel describes Gottfried in this way: "He accepts everyone unconsciously. Such a judgment on human nature is very cruel, and its cruelty may exceed the behavior of rejecting everyone out of impatience. Those who reject others , I still have great expectations for human nature." On the other hand, the novel describes Irina as "casual, or indifferent", "sitting there all day long, watching quietly".

Thinking, perhaps what Arendt was doing all day long, "two into one", "my silent dialogue with myself". Arendt not only thinks, but also smokes. As Anthony Scott says in his review of Margaret von Trotta's biography, thinking and smoking are the same from the outside. I used to think there was something Kantian about smoking. When you smoke, when you puff, you build analyzes and frames, but they all come from the same point. Smoking is especially useful for female writers because it focuses your attention and gives you a smokescreen that keeps out the buzzing bugs.

McCarthy said Arendt liked to smoke during speeches "as long as the fire laws allowed it." Jan-Breuer said, "As a patient, Arendt was very stubborn, which made everyone impressed. She recovered well, but as soon as the oxygen cylinder was removed from the room, she started Smoking, not eating properly, drinking copious amounts of coffee as usual, and acting deliberately irritated by all efforts to calm her down."

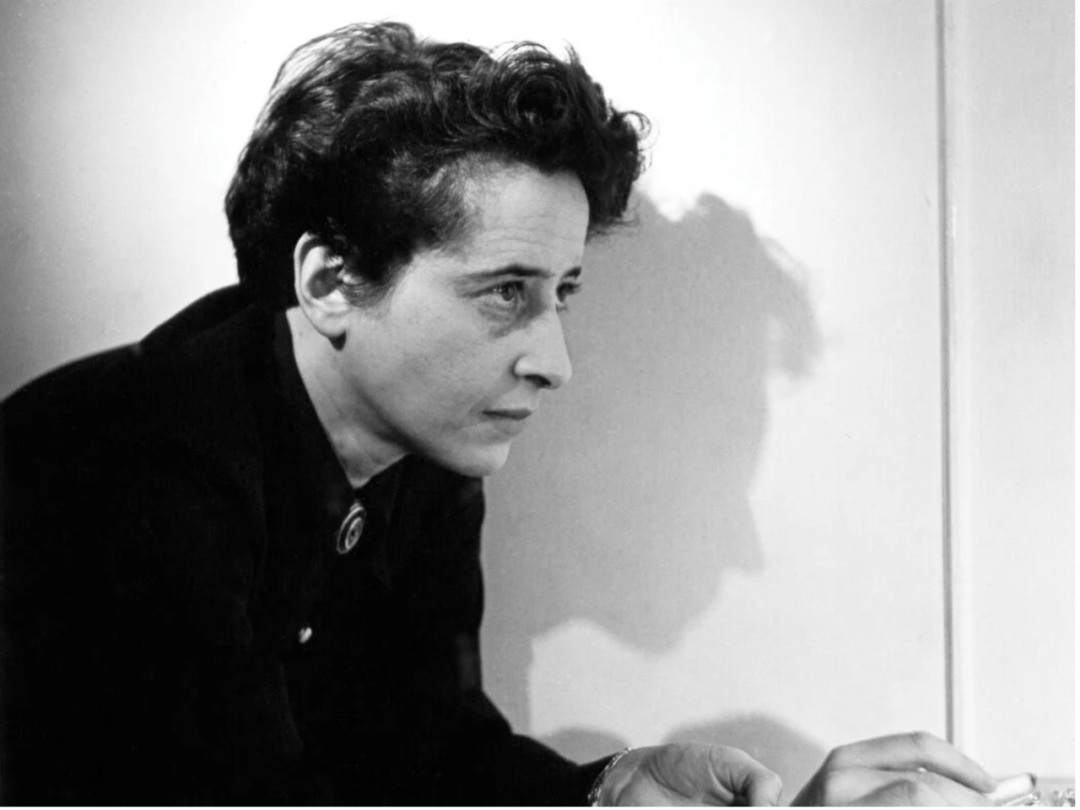

The cover of Hill's Arendt is lovely, a classic 1930s photo: but you might miss the cigarette in hand and the glass ashtray in the lower right corner. However, in another photo taken at the same time in the book, you can't miss the cigarette. Arendt, in this photo, has deep bags under her eyes, a puffy face, hands clasped together, and a cigarette in her mouth. The ashtray was full of cigarette butts, next to what appeared to be Rizla cigarette papers.

borderline female thinker

Arendt was born in Hannover in 1906, the only child of a well-educated, non-believing Jewish family. Her father, Paul, was an electrical engineer and had a large library—she said in an interview with Gauss that she first read Kant at the age of 14. Arendt's family leaned toward socialism, especially her mother, Martha. Arendt's "impressionist, romantic" admiration for Luxembourg probably began when Martha took her to a meeting in 1919 about the uprising of the Spartacus League.

In 1909 or 1910, when Arendt was three years old, the family moved back to Königsberg, the city where her parents grew up. Paul suffered a severe weakening from syphilis and died in 1913. Arendt did not like the stepfather whose mother remarried, nor did she like the daughters of the stepfather. In 1922, she was expelled from high school for organizing her classmates to boycott their teachers. She qualified for university entrance in Berlin.

Arendt mentioned in the interview with Gauss, "I can only say that I am always sure that I will study philosophy. For me, the question is: either study philosophy or give up myself". Arendt heard rumors about a brilliant young professor at the University of Marburg: "Thoughts are resurrected again, cultural treasures of the past, things once thought dead, are awakened to speak".

So, Arendt went to the University of Marburg and took two Heidegger courses "Basic Concepts of Aristotle's Philosophy" and "Plato's <Wise Men>". Heidegger said, "When you use the words 'being', obviously you are already familiar with the meaning of these words, but although we once thought we knew it, we are now confused and disturbed." Arendt and Heidegger—a brilliant young eighteen-year-old and married professor twice her age—started a sexual relationship and then tried to end it. Arendt first went to the University of Freiburg to study with Husserl, and later to the University of Heidelberg to study with Jaspers. For the rest of their lives, the relationship between the two was cut and cut. Heidegger, McCarthy says, was Arendt's "great love affair."

Apparently, Arendt was shocked when Heidegger joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and obeyed orders to fire his non-Aryan colleagues. She had no contact with Heidegger for many years. But she seems to have reunited with Heidegger in 1949, and lamented how poor his moral and political judgment was: "Once upon a time there was a fox who knew nothing of cunning, who was not only caught in a trap, but could not distinguish What is a trap and what is not...he built the trap into his lair." Arendt's own more phenomenological works—The Human Condition, Between Past and Future—use the shared world , man-made space, instead of man's heroic struggle with existence. The emphasis on "newness" in her works is largely to criticize Heidegger's obsession with "being towards death".

In 1929, Arendt dated Günter Anders. He was a young German-Jewish writer-intellectual. One reason she married Anders was because her mother liked him, and the other reason she liked his mother. Anders was writing a faculty thesis at the University of Frankfurt, although it was thwarted by Adorno (this was one reason Arendt hated Adorno for life. Another reason was that Adorno took his mother's Italian surname, while without using the father's Jewish surname). At the same time, Arendt received a grant to study German Romanticism. This project became Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewish Woman. It was largely completed in 1938, but was lost and finally published in 1957.

On May 19, 1771, Rahel Levin (Rahel Levin changed his surname to Varnhagen after marriage in 1814) was born in a wealthy Jewish family in Berlin. She was a famous salon hostess in Berlin at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. She received Humboldt Brothers, Friedrich Schlegel, Schleiermacher, Heine and many other famous thinkers and writers, and she was also a letter writer. . Rahel deeply felt the discrimination against the Jews by the Germans at that time, as well as the various restrictions she suffered as a woman, and criticized and reflected on these status quo in her letters. Hannah Arendt wrote a biography "Rahel Varnhagen" for her. Image and text source: https://weibo.com/7459918425/Kgf44fUlj?layerid=4638711603791505

Rachel Varnhagen (née Levin) has never published a work—how could a Jew and a woman in early 19th-century Berlin publish? But she read Goethe, wrote thousands of letters, and put great poets, mighty diplomats, ordinary people like herself into conversation in the attic salon, "In the time of Frederick II, this sun-drenched land There is room for every kind of plant in the land."

Then, however, the "Weltgeist" (Weltgeist) descended on Jena, and the winds changed. "People once again picked up social prejudices, which intensified and even became violent and barbaric exclusions." In 1814, Rachel married the Prussian diplomat Carl August Wahnhagen, and converted to Christianity. "Jews in the 19th century, if they want to get ahead, they can only become upstarts." Rahel, however, is too sensitive, brooding, and good-natured to be a fully successful sycophant, eventually reverting to Jewishness at the bedside. Jewish identity, "the thing I've been ashamed of all my life," is ultimately seen by her as "the last thing I want to give up now."

Varnhagen, Luxembourg, and Arendt are the three marginal female thinkers at the core of Gillian Roth's "Broken Intermediary" (1992). Although they were excluded from all clubs because of their race and sex, they saw this exclusion as "an advantage, both in literature and in life". In Arendt's words, "it is precisely a loophole. Through this loophole, the exile can see the whole picture of life".

Latest articles (continuously updated)

182. So it's all a scam! | Frele's Horizon (III)

183. In -Depth Interview|Anthropologists Walking in Afghanistan: The Taliban is a Passively Accepted Option

184. In the Name of Body Art | Fraleur's Horizon (IV)

185. Yao Hao x Wu Yuehan: Cells, Data and Suffering People

186. Field series | Exploring the world of prosthetics

187. Talk about writing | Xu Jing: Not a perfectionist

188. In memory of Arendt | We must think (Part 1)

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More