Lan Shiling: In China, the 1980s were buried but not dead

In China, the eighties are buried but not dead

Lan Shiling/Text

Wang Liqiu / Translated

Julia Lovell, “The 1980s Are Buried but Not Dead in China”, FP, October 15, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/10/15/the-1980s-are-buried-but-not-dead- in-china/ . The translation is for academic exchange only, please do not use it for other purposes. The opinions expressed in this article represent the author's own opinions only, and the content is for reference only.

Lan Shiling is Professor of Modern Chinese History and Literature at Birkbeck College, University of London.

Wang Liqiu, born in Mile, Yunnan, Ph.D., School of International Relations, Peking University, lecturer, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Harbin Engineering University.

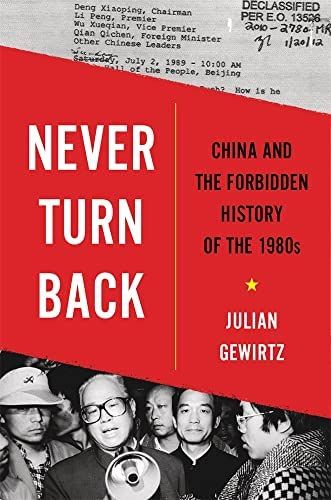

This is a book review of

Julian Gewirtz, Never Turn Back: China and the Forbidden History of the 1980s , Harvard University Press, 432pp., $32.95 (Hardcover ), October 2022.

When I started visiting China in the 1990s, the 1980s felt far away. In books in English about China's 1980s, I read about a time when the basics of life were openly and intensely discussed, including the legacy of the Mao era (especially its most destructive movement, the Cultural Revolution), Western capital The practical significance of socialist society to socialist China, and the role played by the Communist Party of China (CCP) in the modernization of this country.

As a first-time visitor, the China I experienced first-hand was very different: a place where energy was spent chasing a new speculative market economy, where freedom of the press seemed limited to moving leaders back and forth, first published in the People's Daily photo. By this time, the "China model" seemed to be set, that is, high economic growth presided over by authoritarian one-party rule. In domestic public history, the memory and certainty of the eighties—a decade full of open, imaginative possibilities—has been erased.

Julian Gewirtz's excellent new book, Never Turn Back: China and the Forbidden History of the 1980s , offers what is written in English so far, The most detailed analysis of the intense discussions about China's political, economic, and social future that was active in the 1980s. Since Xi became the "Supreme Leader" in 2012, the control over historical writing and material acquisition has been greatly strengthened. Of course, China's zero-clearing policy also prevents most Western researchers from going to China to stay in China for about two and a half years, and we don't see the prospect of reopening at present.

But the tenacious and resourceful Gewitz, who has amassed all sorts of illuminating first-hand material through his long-term focus on the eighties—leaked internal documents, oral histories, flea market propaganda instructions—is also convincing. used these materials.

His book begins with the end of the Cultural Revolution and Mao's departure. Gevitz was once a scholar at Harvard University and now serves as the director of China affairs at the National Security Council of the United States. He admitted that in the early 1970s, as Feng Ke, Ma Jiashi and others had shown, farmers had already begun to divide private plots and resume private production to a certain extent. But when Mao died in 1976, poverty and underdevelopment remained widespread.

The roving researchers found striking poverty in the countryside. In light and heavy industry and household consumption, China lags behind the West and Japan by several years or even decades. Ideologically, the countryside is also on the verge of collapse. At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s, the cult of Mao reached its peak. When Mao's designated successor in 1971, Lin Biao, who launched the Cultural Revolution with Mao, died in a plane crash while fleeing after allegedly attempting to assassinate Mao, the enthusiasm began to fade.

Immediately after Mao's death, party elders purged his closest allies (including his wife) and ended the Cultural Revolution. Obviously, the rules and regulations of ideology are gone, what can be used to replace it? The first option is the "two whatevers" proposed by Hua Guofeng, who directly succeeded Mao, during his brief period in power: "We will firmly uphold whatever decisions Chairman Mao makes; we will unswervingly follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao makes." .” The harder choice was made by Deng. Deng, who was roughly the same generation as Mao, survived the persecution of the Cultural Revolution with extraordinary tenacity, and deposed Hua in 1978 to become the leader of the CCP. His solution to the complex economic, political, social, and cultural conundrum left by Mao was "modernization." And so, for the next eleven years, the country and the party debated — sometimes behind closed doors, sometimes directly in the streets and squares of China’s largest city — what the term meant.

For the most part, Deng sticks to a simple, optimistic definition. As Gevitz writes, he hopes that modernization means becoming "richer" by "liberating the productive forces." He ended the frenetic intervention of the Mao era by giving farmers and entrepreneurs "more freedom to decide what to grow, and encouraging new forms of ownership to make and sell clothing, gizmos, furniture, and so on." He is also willing to consider political reform as long as it promotes economic and market reforms. He is willing to decentralize power, tighten business regulations to boost entrepreneurial confidence and activity, and retire diehards of the old ideology to make way for capable technocrats.

But Deng's gentle, economically-focused proposals for political reform also emboldened others -- including those deeply embedded in the political system and liberal intellectuals -- to offer more extreme criticism of China's socialist system. In the fall of 1980, a party scholar called for an end to party control over the economy, culture, and media, and for independent publishing and the judiciary. As time went on, discussions about sweeping political reforms gradually became normalized in the once-orthodox venue. The pages of the People's Daily were also filled with radical proposals: that Chinese socialism under Mao would oppress individuals as brutally as bourgeois capitalism; that thought and speech should be "more and more open and free."

The mismatch between the conservative leanings of the CCP leadership and the unrestrained minds of the rest of the political and intellectual elite created profound instability. The most notable cooperation and conflict in China in the 1980s occurred between Deng and his protégé Zhao Ziyang. Zhao, a pragmatic premier and party secretary at the time, advocated that China should be fully open to the global economic system.

Deng and other high-ranking elders are also happy to welcome foreign investment and technology, with which the country can catch up with the West and Japan. But other types of Westernization (political, social, cultural influences) creeping in after economic easing are deeply uncomfortable. Deng said in 1983, "When the window is opened, it is inevitable that flies and words will fly in." As a result, throughout the 1980s, issues of "spiritual pollution" (pernicious external influences of all kinds, including hair perms, lipstick, smuggling, and Jean-Paul Sartre) and socialist ideology were becoming increasingly relevant to global markets While there is endless debate about whether a combined China will work, China has also been cycling between liberalization ("letting go") and tightening ("tightening").

The tragic climax of the 1980s—the bloody crackdown on nationwide protests—is often imagined as a political struggle between pro-democracy students and those determined to keep power at all costs sir. But Gewitz also emphasized, at least as much, the debate over an overheated economy. From mid-'88, the leadership debated the risks inflation posed to political stability. Zhao, backed by Deng most of the time, stuck to his mantra of high economic growth even as urban prices soared; in 1988, China's inflation rate was at least 30 percent.

By 1989, the Chinese government was facing a crisis of legitimacy fueled by socio-economic turmoil and Western-style democratic dreams. At this juncture, economic instability makes Zhao seem less reliable. When protest calls for "democracy and freedom" emerged that spring, Zhao's permissive stance—opening China to the global system and to the political and economic implications of such liberalization—was rebuked by party elders , the latter argued that such a position encouraged rebellion. Gewitz reminds us that economics and politics are "inseparable" to "protesters with different motives, from demands for democracy to the eradication of corruption and inflation." Some of the earliest protesters in the square were not students but workers worried about rising prices.

The decision to use violence to quell the protests defined the future direction of the Chinese leadership, in stark contrast to decisions made in Eastern Europe that same year. After the hardliners won the argument and sent the PLA against the people, they also rewrote the history of the 1980s, describing it as a period of steady economic growth simply because Zhao failed to maintain "ideological and organizational purity" , only briefly interrupted. They reshaped China's road to modernization, rewriting it as a road that required obedience to "a 'core' leader" and the CCP's definition of Marxism-Leninism-Mao Thought, effectively suppressing public dissent on Chinese politics.

Thus, the discussions of the 1980s (these discussions were often heated, but they were also open and fascinating) were officially erased from history, along with Mao himself. The way the CCP handled 1989 also determined the general attitude of the leadership toward the West thereafter. In the aftermath of the crisis, China's leadership described the United States and other Western countries as plotting to turn "socialist countries into capitalist democracies." It was manipulation by foreign forces that led to the turmoil. Beijing Mayor Chen Xitong explained in 1989: "Some political forces in the Western world always try to make socialist countries, including China, abandon the road of socialism, and eventually fall into the rule of international monopoly capital and into the track of capitalism. long-term fundamental strategy."

During this decade, people have explored various paths for China's future. Gewitz's book offers a fascinating and authoritative account of these paths, long buried by state-run official history. It evokes the dynamism of Chinese society in the post-Mao era, and how its response to the chaotic emergencies of the late 1980s profoundly shaped China thereafter. Today, elite politics in China insist that China can only be a successful, wealthy country under an authoritarian one-party government. Geertz's important history of the 1980s reminds us that there is still much that can be debated in China, then and now.

Attachment: original book catalog

Introduction: The History of Taboo

1 Reassess history and reshape modernization

Part I: Ideology and Propaganda

2 Mental pollution and sugar-coated bullets

3 The bane of bourgeois liberalization

Part Two: The Economy

4 Liberate productivity

5 Market forces

Part III: Technology

6 Response to new technological revolutions

7 The question of life and death of the nation

Part Four: Political Modernization

8 masters of the country

9 Fearless Exploration

illustration

Part Five: Before the Door

10 two rounds of applause

11 Great Flood

12 We came too late

Part Six: The Door and Beyond

13 Political Repression and the Narrative Crisis

14 Reshaping reform and opening up

15 Survivors of Socialism in a Capitalist World

Conclusion: New Era

abbreviation

note

thank you

index

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More