「Cultural Studies」Chinese International Students and Internet Nationalism

summary

Overseas Chinese students have recently discovered a phenomenon: after leaving their homeland, their attitudes towards China are more positive than before. In other words, when they become part of the Chinese diaspora, they embody a strong nationalist ideology. The empirical evidence I provide to support this observation is a survey sent by SFU in March 2018 to obtain the demographic distribution of international students. However, in this survey, SFU classified Hong Kong and Taiwan as countries, which hurt the hearts of some Chinese international students, who asked SFU to correct their classification by emphasizing that Hong Kong and Taiwan are integral parts of the People's Republic of China. I will use this as a case study to analyze why Chinese international students become nationalists and how to reproduce it. "Pinky" is a specific term attributed to those cybernationalists, and I think language plays an important role in the reproduction of this cybernationalism.

introduction

In recent decades, due to China's rapid economic development, many students have chosen to study abroad to broaden their horizons and receive high-quality education. A recent phenomenon discovered among Chinese students studying abroad is that more and more people have become online nationalists. They accept official nationalism and practice it online. In this article I draw this point from the social debate sparked by the March 2018 SFU survey. I then want to analyze the relationship between international students and online nationalists (Little Pink) in a broader context. Finally, I will conclude that language is a major factor that can inspire and reproduce Chinese international students’ online nationalism as well as their psychological experiences and class backgrounds.

The reason this topic interests me is that, in my own experience, the process of internationalization of thinking is accompanied by the deconstruction of nationalism. In other words, after I left the country, I realized that I had been deceived for years by the nationalist political rhetoric of the Chinese Communist Party. I met and talked with friends from Taiwan and Hong Kong. A fundamental difference in national identity emerged between us, which reminded me of the relationship between Taiwan and China. I used to think that Taiwan was undoubtedly part of China, which was the result of our national education and media propaganda. When I first heard my Taiwanese friends call me “you are Chinese”, I didn’t feel happy because all the “ideological state apparatuses” (Althusser, 2014) such as the media and school teachers told I, Taiwan, am part of it. China should not make any difference in terms of national identity between Taiwan and China. However, this empirical encounter disproved all previous rhetoric constructed by the CCP. As I learn more about Chinese history and read more academic works on nationalism, such as Imagined Communities (Anderson, 2016), I have gained the knowledge to deconstruct CCP nationalism. This was a major change in my mind after leaving China. However, while I saw that many Chinese international students were still trapped in this nation-state discourse, and that many of them were not nationalists when they were Chinese students, I began to research this.

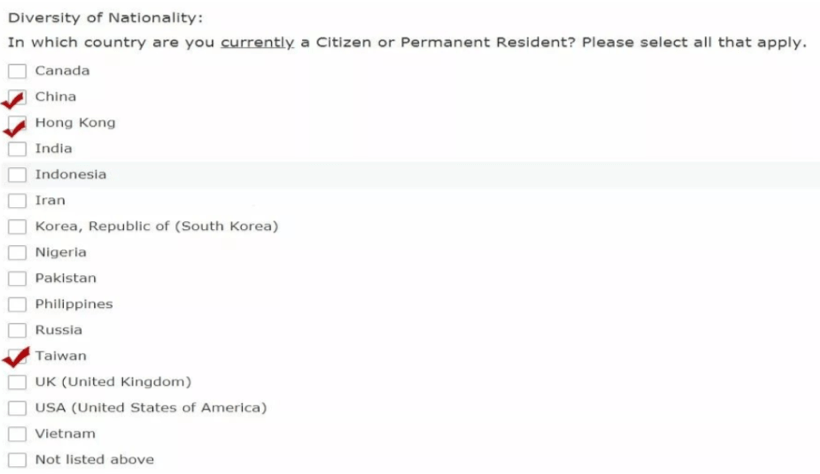

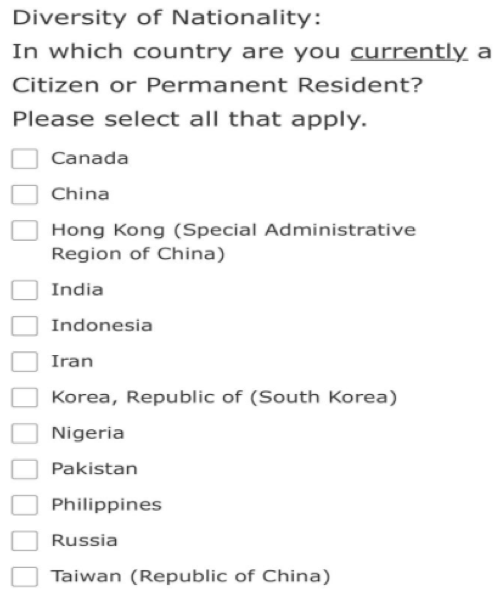

To support my observations, I would like to provide empirical evidence from what happened at Simon Fraser University this year. On March 23rd, when I was scrolling through my social media, I saw a lot of Chinese international students complaining about SFU placing Hong Kong and Taiwan in the country category equally with China in a survey (see Figure 1). They want to know when Hong Kong and Taiwan became "countries"? This ignited their nationalist sentiments and many of them sent emails asking SFU to correct this huge mistake. The next day, SFU added a stent after Hong Kong and Taiwan (see Figure 2).

I would like to quote a passage from a student who wrote an email to SFU expressing their feelings of disappointment as a prime example of analyzing their errors and underlying ideology:

I am a Chinese international student. My name is xx and I am a Chinese international student. I was very disappointed when I saw Hong Kong and Taiwan selected as the countries in the survey. As a Chinese, following the 1992 Consensus is the basic respect for our country. At the same time, I respect my family and all Chinese people. So, I will point out clearly that there is only one China on this planet. Hong Kong and Taiwan will not be China’s surprise countries. All Chinese students studying abroad follow the wishes of the Chinese government. I demand that you correct your mistake immediately. This email conveys the wishes of all Chinese FIC students and Chinese people already at SFU.

I want to point out something here. This is a typical Chinese student who was raised from the nationalist education of the Communist Party without any critical thinking skills and only dogmatically supports the government. He does not have good logical thinking and cannot distinguish between universality and particularity (I don't know how he can represent all Chinese students in SFU and FIC?). He doesn't even care about the political debate between China and Taiwan, namely why the current president of the Republic of China, Tsai Ing-wen, does not recognize the existing 1992 Consensus, while the former president of the Republic of China, Ma Ying-jeou, did. From my perspective, those Chinese nationalists are the ones trapped in Plato’s cave, believing that all the shadows they see in front of them are the real world (Plato, 2015).

More importantly, I would argue that in this case, most Chinese international students make a big mistake because they subconsciously translate the English word "country" into Mandarin "country", which contains different connotations. Literally, there is no clear difference between "state" and "country" in Mandarin, both of which are translated as "country." However, from a political philosophy perspective, the Mandarin word "国" is more closely related to "state" than to "country". For example, the United Kingdom is a state made up of four independent countries: Northern Ireland, England, Wales, and Scotland. In Mandarin, we only refer to the UK as a country, not these four countries. Therefore, I can conclude that the accurate translation of "state" is country, and there is no one-to-one translation of "state" in Mandarin.

Furthermore, due to this inaccurate and subconscious translation, Chinese overseas students decontextualize the word “country” and relinguistic it as “国”, which I call “speech governance” (Jing Tsu, 2011) , which means that when they stay in English-speaking countries for a long time, they cannot think in English but in Mandarin. According to epistemological contextualism, S knows P if and only if S depends on the context of P. Therefore, to understand whether HK and Taiwan can be called countries, we need to understand their background. I found some country and state definitions:

(1) Definition of Country:

1. The land of a person's birth, residence or citizenship. (Webster)

2. Regardless of physical geographical location, within the modern internationally recognized legal definition defined by the League of Nations in 1937 and reaffirmed by the United Nations in 1945, residents of a country are bound by the independent exercise of legal jurisdiction. (Wikipedia)

Definition of state:

The state is a set of institutions and professionals responsible for managing important aspects of the life of a territorially limited population and extracting resources from that population through taxation. Its provisions are backed up by force if necessary. It is recognized as a state by other similar countries. (Encyclopedia of Political Science)

This definition has four elements: the regulatory character of the state, the coercive aspect of the state apparatus, the extraction of resources from the population, and the role of the state as a unit (in fact, the fundamental and irreducible unit) in the field of international relations. These four elements can be considered constants in any interpretation of the state. (Encyclopedia of Political Science)

According to the Basic Law of Hong Kong and the Constitution of the Republic of China (Taiwan), Hong Kong and Taiwan are able to issue permanent residence and citizenship that meet the definition of country (1), and have legislative and independent judicial powers, including ultimate auxiliary, that meet the definition of country (2). Therefore, I conclude that Hong Kong and Taiwan can be called counties in this context. The discourse of the SFU survey does not go beyond this context: "Which country are you currently a citizen or permanent resident of?" This meets definition (1).

After clarifying the background of the "country", I think there is no need for Chinese international students to make such a huge reaction. That day, I posted an article telling them what “country” means in English and why we shouldn’t think about it in Mandarin. I then received some encouragement from liberals who thanked me for providing them with more knowledge, as well as attacks from those who abused me as "kissing white people's ass".

Exactly what Plato (2015) describes in The Republic, when the first person to break the chain and get out of the cave and see the real world returns to the cave and tells the others that all the shadows before them are illusions and that no one will believe him. "Speech governance" is their twin chain, and the fantasy they see is the CCP's nationalist ideology (the party-state and one China). They have no inclination to think outside the box and criticize the beliefs they once believed. From my point of view, learning is a process of disenchantment. So, it raises my question, why do Chinese international students become nationalists after leaving China, and how is the discourse of nationalism reproduced among them? I will answer these questions in the following sections.

little pink

In this section, I will introduce a term “little pink” to identify young Chinese online nationalists. In 2016, an article in The Economist, "The East is Pink," showed that more and more young Chinese people are using "the Internet as a battlefield." A common view with disparate masculinist nationalists is the latest wave of nationalist activity, known as the 'angry youth', which hurled the US Embassy in Beijing (Dumbaugh, 2000) and the Japanese car debacle (Branigan, 2012). Being "little pink" means feminine, using soft emotional words of temptation and romance.

The word "Little Pink" comes from a pink discussion forum about boys' love in Jinjiang literature. The term is associated with nationalism in Taiwan's 2016 independence elections. Little Pink, bypassed the Great Firewall and logged into Facebook to protest Taiwan’s independence in the “Cross-Strait Meme War” (Fang and Repnikova, 2018). They use many funny, persuasive and self-edited internet memes (Phillips, 2015; Shifman, 2014; Wiggins and Bowers, 2014) rather than rock and roll statements as their weapons of persuasion and luring Taiwan to give up its independence.

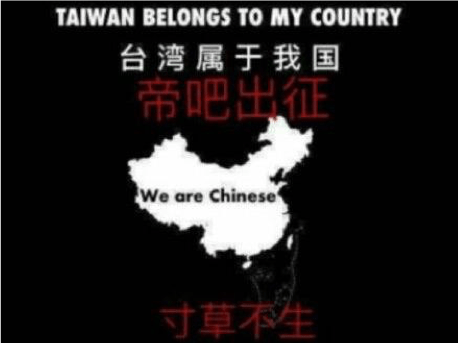

Meme 1 is a typical meme by Little Pinks claiming that Taiwan is part of China, identifying Taiwanese people in Chinese.

Memes 2 and 3 use more aggressive language to swear at Taiwanese people. In meme 2, it says "Such an ugly guy, to even want to be independent, is stupid." On the girl's t-shirt, it prints "I LOVE CHI-NA" and "Made in China" in the upper right corner. Meme 3 says "I am the heir of socialism, you are nothing. Don't force me." Prints "Made in China" as the watermark.

Little Pink's words in these memes indicate the strong nationalist ideology behind them. I call this kind of nationalism Sinocentrism, an ideology that places China at the center of the earth. In a nationalist context, Sinocentrism means using Chinese as an umbrella term to identify all people of Chinese descent, including all Chinese in Hong Kong, Taiwan and overseas. Therefore, Chinese nationalists cannot see any difference between Taiwanese and themselves. They never try to understand others and see things from a different perspective.

Due to nationalist education in mainland China, students may lose their interest in critical thinking and truth-seeking. There is no doubt that they may believe that "Taiwan is part of China." No one wants to read history books that acknowledge the circumstances of the Chinese Civil War. They don't even know the difference in political systems between Taiwan and China. As a result, this controlling class ideology became the cultural hegemony of nationalists (Gramsci, 1971). Chinese students studying abroad may be influenced by the kind of hegemony that makes them potential nationalists.

The realization of nationalism among Chinese students studying abroad

In this section, I will elaborate on my perspective on why Chinese international students become online nationalists or little pinks, and reveal the importance of language in this realization process. I will make the argument from the following aspects: cybernationalist practice as everyday nationalism (Billing, 1995), psychological overseas experience (Dong, 2017), classroom context and course selection (Dong, 2017). All interact organically with each other in their overseas experiences, casting shadows in front of them. Once they are able to break apart part of this straitjacket, they discover the absurdity and irrationality of nationalist discourse.

Everyday Nationalism and Psychological Overseas Experience

billing defines banal nationalism as:

“…the term everyday nationalism was introduced to cover the ideological habits that enabled the mature nations of the West to replicate them. It is argued that these habits have not disappeared from everyday life, as some observers have argued. Daily , the nation is directed or "marked" in the lives of its citizens. Far from being an unstable sentiment in mature nations, nationalism is endemic."

To explain Little Pink's behavior, everyday nationalism is a fascinating concept. As Billing defines it, everyday nationalism refers to the reproduction of everyday practices of nationalism, such as the national anthem, the flag, and the lives of citizens. For Chinese citizens, they have no opportunity to exercise their political rights, but the ruling class induces them to speak out in nationalist discourse, especially things related to territory or sovereignty. This discourse is reproduced through the media and people may become accustomed to this way of thinking. Therefore, when international students in China encounter different discourses about China and Taiwan, they may feel angry and disappointed because what they hear over and over again is different. Claiming to be a nationalist is the only way they can reconcile this feeling, and showing love for China can help them find unity with other Chinese people, i.e. collectivism.

Likewise, being a nationalist can benefit them from psychological difficulties. As Dong (2016) said, most international students will dream that abroad is the paradise they arrive, assuming that it is a place of fair competition, freedom, personal success and wealth. However, this is not the case when they see that discrimination, racism and poor neighbors are common experiences for most of us. They easily fall into the temptation of nationalism because only a strong homeland can protect their citizens from oppressive imperialism. So, so far we can see the pragmatic version of nationalism, they may not really believe that China is a perfect country and the CCP is the best party in the world, but for some practical reasons they choose to be national ists, or in other words, nationalism is realized in this pragmatic way.

Classroom Background and Course Selection

Tuition fees for Chinese international students at SFU are three times that of Canadian citizens, while at UBC it is five times. Only middle- and upper-class families can afford such high tuition and daily expenses for their children. All of these are beneficiaries of the reform and opening up policy. Many of them may return to China for further development, and the government will check their political leanings. Nationalism may be a veneer of security or true belief in them, as job opportunities may be skewed towards CCP members.

Recently, many companies have established party branches to show their attitude towards the CCP. Therefore, it is very dangerous for individuals to openly express different voices about politics. I think that due to self-censorship, many Chinese international students tend to ignore politics or choose the safest path (nationalism).

Most importantly, I was shocked when I saw statistics about the proportion of courses chosen by Chinese international students: Business Management (26.5%), Hard Sciences (21.3%), Engineering (19.7%), Social Sciences (under 8 %), and humanities (less than 1%).

Less than 10% of those studying in the social sciences and humanities have barriers that prevent them from developing critical perspectives that deconstruct the concept of the nation-state. Behind such a low proportion of liberal arts and social science students, I point to the high level of language requirements for admission and course content that many international students would be willing to study in the first place. I asked my friend why did you choose business or economics instead of anthropology or philosophy? Aside from financial reasons, a very common answer I get is language requirements. Many Chinese international students believe their English is not enough to complete their courses or graduate in literature and social sciences. In fact, literature and social sciences have much higher language requirements than business administration, science and engineering because we read and write a lot. Language proficiency is a prerequisite for these majors.

From my own experience, I struggled in my first and second year and if I couldn't pass the writing course (Fal X99) I would be kicked out. I spent more than four or five hours a day reading course material and additional readings, which gave me spinal problems. After I got through the toughest time in college, everything became easier.

I argue that language dialectically makes Chinese international students nationalists in two ways. On the one hand, most people cannot think in English and can only use Mandarin as the default language for "speech governance"; on the other hand, many of them do not choose to do so because of the high level of language requirements that prevent them from learning critical knowledge and theory. Humanities and Social Sciences. Their nationalist theme is constituted by "power/knowledge" (Foucault, 1980). In other words, thinking in Mandarin can easily lead them to fall into nationalist discourse, while instead of studying literature and social sciences they lose the opportunity to deconstruct nationalism as a critical perspective. Therefore, in the dialectical language relationship between Chinese and English, the potential of Chinese international students' nationalism is realized. Nationalism can be a refuge for “marginal people” who need to reconcile their psychological difficulties with political security. All these factors interact organically to build them into Little Pink.

in conclusion

In this article, I discuss the relationship between nationalism and international students in China, starting with a case study of the SFU “nation” debate. I pointed out a major mistake that made them confuse the English term "country" with the Mandarin term "country", and through a critical analysis of "speech governance" (Jing Tsu, 2011), they decontextualized "country" and re-textualizing it into the nation, leading to misunderstandings of English discourse. They then reacted nationalistically, demanding that the SFU show that Hong Kong and Taiwan are part of China. I use the term "little pink" to analyze this phenomenon, which is a negative connotation used by Chinese free people to criticize youth online nationalism. Some overseas students display Little Pink characteristics and use the Internet as a battlefield for their battles, claiming that Taiwan must be part of China, following the hegemonic (Gramsci, 1971) official nationalist discourse as a practice of everyday nationalism (Beer, 1995 ). In order to understand the process of realizing potential nationalism among Chinese overseas students, it is important to view it from the organic interaction between numerous factors, including psychological overseas experience (Dong, 2017), classroom background, and course selection (Dong, 2017). If we penetrate such appearances, what I find is a dialectical form of language oppression, where on the one hand students may be oppressed by Mandarin, and on the other hand, the seeds of nationalism are oppressed by English.

References

- Anderson, BR (2016). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

- Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. London: Sage.

- Country. (2018, July 28). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Country

- China Requires All Publicly Listed Companies to Establish Communist Party Branches. (2018, June 18). Retrieved from https://www.theepochtimes.com/china-requires-all-publicly-listed-companies-to-establish-communist-party -branches_2565214.html

- Dong, Y. (2017). How Chinese Students Become Nationalist: Their American Experience and Transpacific Futures. American Quarterly, 69(3), 559-567.

- Foucault, M., & Gordon, C. (1980). Power / knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972 - 1977. New York: Vintage Books.

- Fang, K., & Repnikova, M. (2017). Demystifying “Little Pink”: The creation and evolution of a gendered label for nationalistic activists in China. New Media & Society, 20(6), 2162-2185.

- Gramsci, A., & Hoare, Q. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. New York: Lawrence & Wishart.

- Hydrant ( http://www.hydrant.co.uk). (nd). United Kingdom. Retrieved from http:// thecommonwealth.org/our-member-countries/united-kingdom

- Kurian, GT (2011). State, the. In The Encyclopedia of Political Science (pp. 1595-1598). Washington, DC: CQ Press

- P., & Cooper, JM (2015). Plato: complete works . London: Hackett Pub Co Inc Press.

- Rysiew, P. (2007, September 07). Epistemic Contextualism. Retrieved from https:// plato.stanford.edu/entries/contextualism-epistemology/

- Tsu, J. (2011). Sound and script in Chinese diaspora. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- The East is pink. (2016, August 13). Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/china/ 2016/08/13/the-east-is-pink.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More