Who lives in social housing: Debunking the myth of self-payment and pursuing affordable rents

This year marks the tenth year of the Taiwan Social Housing Initiative, and we have invited experts from different fields to jointly write a series of articles. This article is the second in a series of articles, co-written by me and my boss, to talk about the most critical issues of "object" and "rent" in social housing.

The construction of social housing in various countries mostly starts with the concept of "social safety net", that is, through the direct supply of housing resources, the disadvantaged groups who cannot enter the housing market can obtain housing security. Therefore, priority is given to disadvantaged groups for service targets, and it is not until the stock of social housing is gradually increased that a higher income rank will be gradually opened, so that the role of social housing will be changed from "living assistance for the disadvantaged" to "living assistance for the wider community".

However, in Taiwan, "who should live in social housing?" There are three phenomena that are completely different and quite special from other countries.

The first is that "the number is very small, but the scope of care is very wide." Since Taiwan did not start building social housing until the 21st century, the current social housing stock is extremely low (as of June 2020, accounting for about 0.18% of Taiwan's housing stock), but the objects to be taken care of are extremely broad. All households with annual income below the 50th percentile can apply, and the occupancy standard is almost on par with the Netherlands, France and other established social housing countries, and also surpasses the neighboring Japan and Hong Kong. 1

Secondly, in addition to the extremely wide range of occupancy standards, Taiwan's social housing also sets a special "30% vulnerable occupancy ratio guarantee", hoping to protect the vulnerable housing rights while avoiding the phenomenon of labeling. Compared with other countries, there is no such practice of setting a vulnerable security ratio for social housing. Most of the people who meet the qualifications for social housing use a "waiting list" to wait in line.

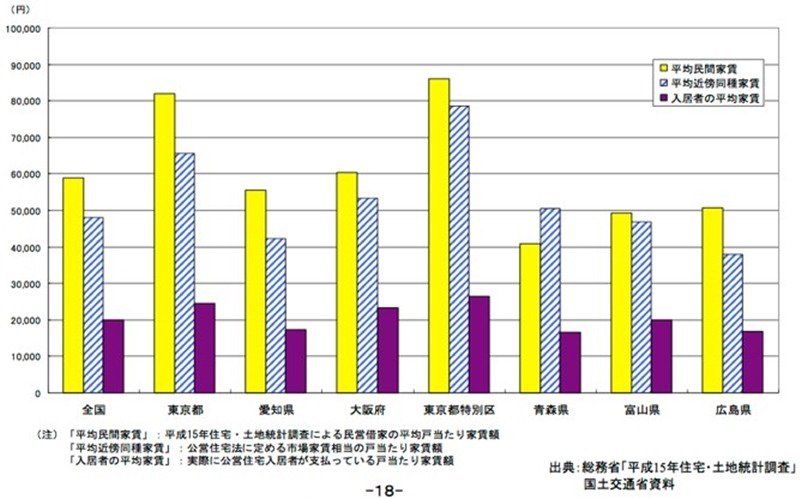

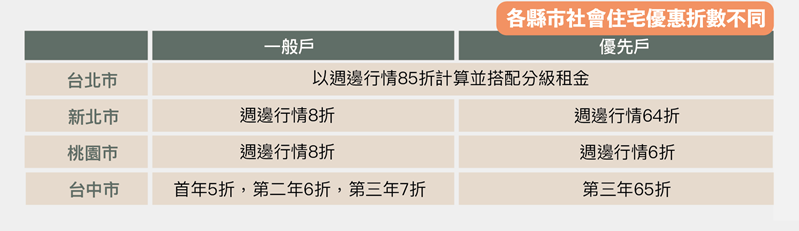

Finally, there is the issue of "high rents in vulnerable situations". The social housing rent in Taiwan is estimated by appraisers, and it is rented at 7 to 15% of the market rent. Although it is lower than the market price, it is still very expensive for relatively disadvantaged groups in social economy. Comparing the rents of social housing in Japan, South Korea, and Hong Kong, most of the rents are estimated based on "income capacity", which is about 30 to 40% off the rents in neighboring areas.

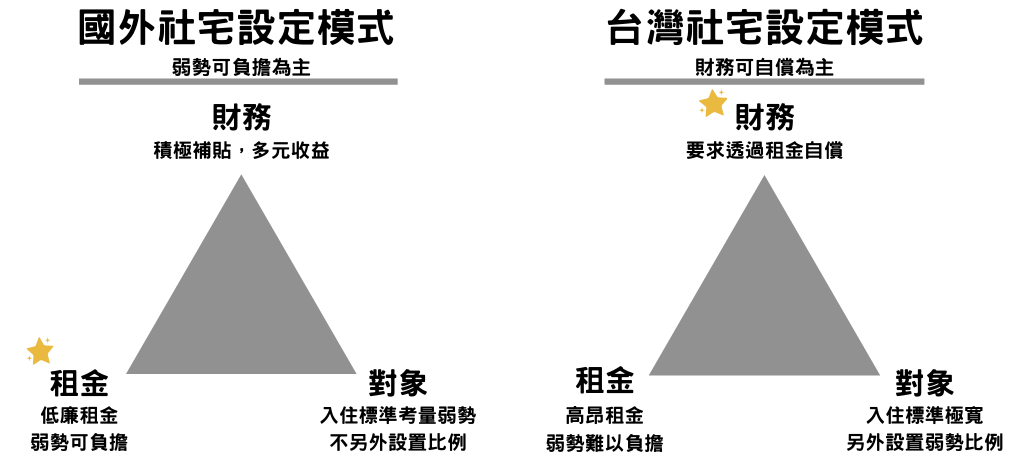

Why do social housing in Taiwan have the above-mentioned special phenomena? We believe that this is because Taiwan's perception of the value of building social housing is different from that of foreign countries. It is limited by "self-compensation" and misinterprets the meaning of "social mixing", which blurs the social safety net responsibility that social housing should shoulder.

The key difference in who to live for: "subsidized" vs. "self-paying"

Generally speaking, the first consideration of social housing as a social safety net is "rescue", that is, to make it affordable for disadvantaged groups, the rent is bound to be relatively low. Therefore, the financial aspect of building social housing is destined to not be self-paying through rent.

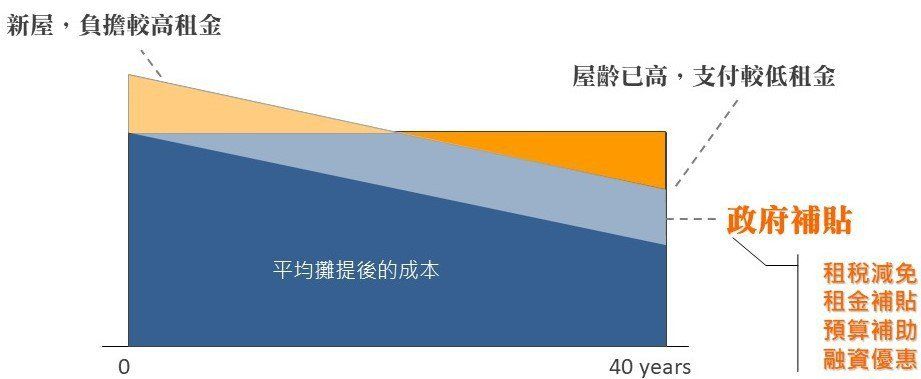

We can see that social housing in various countries is under the premise of "non-self-payment" - from the "direct subsidy" of the early government, to the "cross-subsidy" achieved by the multi-development model with the recent matching - to seek financial sustainability. operate. That is to say, social housing cannot be completely self-paid through rent, and must be subsidized. The difference is only in the effect of saving public funds (Value for Money).

Based on the above-mentioned salvage orientation, social housing in various countries usually only sets the occupant’s qualification threshold (below a certain income), in addition to affordable rent (meaning that the rent expenditure does not exceed a certain percentage of household income, and the more common international standard is 30%) , to ensure that eligible people can afford social housing. At the same time, this eligibility threshold is usually dynamically adjusted based on the number of social dwellings.

Taking South Korea as an example, since the 1990s, "permanent rental housing" and "public rental housing", which prioritized middle- and low-income earners, have been built. , "Long-term Chuanzhen (pronounced as ㄕˋ) residence", etc., to expand the target of care to the middle-income class. After reaching a certain stock of social housing in Japan, since the 1980s, the Central Japan Housing Corporation has been gradually transformed into an Urban Renaissance Agency (UR) that provides rental housing for higher-income earners, and a partnership with local housing communes. Public housing division and division of labor.

However, Taiwan's social housing does not start from the rescue, but highly emphasizes "self-compensation". For example, in 2013, New Taipei Mayor Zhu Lilun launched the "Youth Social Housing BOT", claiming that the city government can build social housing without paying for it; in 2016, after President Tsai proposed "200,000 social housing in 8 years", the first executive director Lin Quan also expressed his hope Social housing should not use the official budget, let alone make it as little as possible.

The key is that Taiwanese politicians generally do not realize that social housing is a policy that must be subsidized and accumulated through a large amount of money, and it is also a part of the social safety net system. In addition, because Taiwan's social housing policy has missed the golden period of economic growth in financial planning2, under the realistic conditions of the country's declining financial capacity, it is naturally more inclined to emphasize financial self-payment.

However, due to the financial requirement of self-payment, the rent setting of social housing in Taiwan is relatively expensive, the disadvantaged groups are more difficult to afford and the risk of rent arrears is higher, so the vulnerable protection ratio must be adopted, and some rent discounts must be given. Also based on financial considerations, the disadvantaged security must be managed to a certain percentage, and the rest of the social housing is rented to households with relatively high economic ability to meet the self-payment goal as much as possible, thus making most of the truly disadvantaged groups excluded from Taiwan's housing system. outside social housing.

"Vulnerable ratio" is actually a distortion of the meaning of "social mixing"

Some commentators pointed out the reason why Taiwan’s social housing needs to set a “weak ratio”: in addition to financial considerations, at the political level, because of the fear that social housing will become a slum or a dead end of public security, that is, refer to the “social mix” of foreign social housing. concept to avoid social housing being affected by labelling.

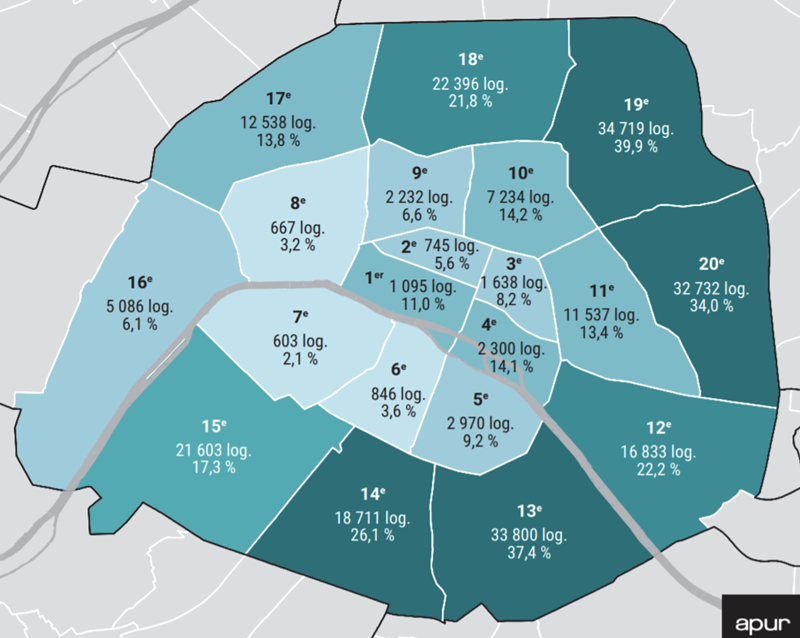

What is social mixing in social housing? In Europe and the United States, social housing was created in a large scale and concentrated in the early days, resulting in low-income and minority-group social housing in specific areas. Therefore, since the 1990s, European and American countries have successively put forward the principle of social mixing as the follow-up principle for the establishment and operation of social housing.

"Decentralization" means that if the proportion of social housing in a certain area is excessively concentrated, through urban redevelopment, multiple types of market (rent or sale) housing will be added and the middle class will be introduced. "Embedded" means that the proportion of social housing in a region is too low, or a new development area still needs to maintain a certain proportion of social housing and should not be fully marketized.

Taking France as an example, the large-scale construction of social housing began in the late 1950s, and in line with the "Zone for Priority Urbanization" (ZUP) policy, the urban fringe area was chosen as the development model of new towns. From the 1990s onwards, realizing the labeling problem of social housing, he began to put forward the three goals of social mixing, and successively formulated the Law on Social Cohesion and Urban Renewal (2000) and the Urban Renewal Plan and Guidance Law (2003). On the one hand, through the renovation plan to demolish some decayed social housing, and build new housing with diversified property rights; on the other hand, in areas where the proportion of new development or social housing is too low, the number of social housing continues to increase.

In other words, the social mixing that Taiwan's public sector talks about completely misreads the context. At the micro level, Taiwan's current single social housing mix of "30% disadvantaged households and 70% ordinary households" is inconsistent with the social mix discussed in foreign countries, and can even be called a false issue; at the macro level , the proportion of social housing in Taiwan is extremely low, and the construction of social housing itself is a concrete practice of social mixing.

It should be added that the failed experience of labeling social housing in Europe and the United States is not a simple residential planning and design issue, which is related to the fact that poverty is highly associated with ethnic minorities. In contrast, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and other Asian regions also have large-scale social housing construction models, but they have never intensified to the level of social riots and demolition.

In fact, Taiwan does not have the problem of too many social housing and too dense labels. At this stage, more problems come from social discrimination and lack of awareness. Therefore, what is more important is how social housing establishes a connection and mutual understanding with its neighbors, that is, the importance of planning and design and community building.

To make housing affordable for the disadvantaged, first implement "affordable rent"

Returning to the core value of social housing "making the disadvantaged affordable", it is necessary to change the thinking of setting up social housing in Taiwan from "self-compensation" to "relief". Its core mechanism is to set an " affordability benchmark ", so that disadvantaged groups can obtain more reasonable subsidies according to this benchmark, which is also a concrete manifestation of the basic spirit of housing subsidies: "the disadvantaged first, fair and reasonable".

It is difficult for Taiwan to provide all social housing to the disadvantaged at this stage, but even if the current ratio of the disadvantaged is maintained, the top priority is to first formulate social housing rents that the disadvantaged households can really afford, so as to avoid "the number is already insufficient, and the disadvantaged cannot afford to rent." situation occurs.

Regarding the affordability benchmark, it was clearly stated in the revision of the Housing Law in 2016 that the government must set the affordability benchmark within two years, but in fact, it has not yet been announced and implemented. In response to this, the Ministry of the Interior responded that the current central government’s income and expenditure surveys are not accurate enough, and to set affordability benchmarks based on these data, it is impossible to really subsidize those in need, but instead will subsidize many “fake” poor people. But the paradox is that the basic data of the current social welfare subsidy distribution also comes from the same household financial and tax data. This statement by the Ministry of the Interior is obviously an excuse.

In the absence of an "affordable benchmark", social housing rental standards and subsidies are not uniform, and the amount is often reduced to bidding. The rent is not set based on the affordability of disadvantaged groups, but whether the rent is affordable or not. Financial self-payment, and even increasing rents according to the surrounding area. 4 As a result, disadvantaged households finally apply for social housing, but they still give up because of rent problems, resulting in a reverse distribution of subsidy resources and reducing the function of social housing as a social safety net.

Where does the budget come from? "Rationalization of Property Tax System" and "Urban Redevelopment Gains"

Another question to be asked to implement the affordable benchmark for social housing is: Where does the budget come from?

Referring to the experience of various countries, in the early stage, a large number of financial subsidies were used to make social housing rents affordable and affordable. Even in the transition period when the stock of social housing reaches a certain proportion, no country has seen "rent" as the main financial self-payment mechanism for social housing, and more diversified financial management models have been adopted, which are combined with "urban redevelopment gains".

Experiences in Europe and the United States, such as the Netherlands and France, have used urban redevelopment to subsidize the construction funds of social housing through the proceeds of market housing, shopping malls, parking lots and other projects; New York has adopted the practice of inclusionary zoning, requiring private development Businesses need to provide a certain amount of affordable housing (which can be regarded as a civil version of social housing). 5

Asian experience, such as South Korea, requires a certain type and scale of urban renewal projects, and must provide a certain proportion of housing as social housing6 ; Hong Kong is through the combination of public housing (social housing) and HDB (similar to Taiwan's national housing). , so that the sales of HDB flats will be injected into the financial gap of public housing. On the other hand, in Taiwan, the government is unrivaled in the world in terms of its proximity to developers in urban development and its excessive volume incentives. However, it is obviously insufficient in guiding development profits back to the establishment of social housing, and it is urgent to improve and make breakthroughs.

Due to the serious shortage of social housing stock in Taiwan, the government should actively try to combine the gains from urban development, and "financial subsidies" are still necessary. The source of finance is nothing but taxes, such as the tax on the integration of real estate and land, which was stipulated in the legislation of the "Measures for the Distribution and Application of Income Tax on the Integration of Real Estate and Land" 7 . The balance allocated by the central government to local governments will be used for housing policies and long-term care service expenditures.

But the fact is that from 20105 to 20108, a total of about 13.7 billion yuan was injected into the long-term care fund, but there was no subsidy for the residential sector at all. Why is it expressly stipulated that the tax should be paid in the housing and long-term care, but there is no subsidy to the housing policy? The problem may be that the government believes that social housing is different from other "social welfare" and that it can operate through rent self-payment, but this approach has instead excluded many people who need to be cared for.

If we look at the financial needs of "200,000 households in 8 years" in the longer term, it may be necessary to think about the "rationalization of the property tax system". For example, the current real property tax rate is only 0.13% 8 , which is far lower than the international standard. If it can be adjusted appropriately and reasonably so that the increased tax revenue can be used as a stable subsidy source for social housing, that is, "take it from real estate and use it for social housing", it should be fair and reasonable.

Conclusion: Building a "financially sustainable" mechanism for social housing subsidies

Social housing in Taiwan is still in the early stages of quantitative development. We must adhere to the core value of "affordable housing for the disadvantaged", otherwise high rents will exclude groups who really need social housing. The primary task in the follow-up is to quickly set an "affordability benchmark" and transform the current "self-paying" role into a "subsidy" that is in line with international standards.

The premise of achieving the affordable benchmark is the further deepening of the financial strategy, that is, the two-pronged approach of "profits from urban redevelopment" and "reasonable reform of the tax system". The former is to review Taiwan's current excessive volume incentives, development profit injection, and cross-subsidization; the latter is to review the current low real estate holding tax and increase the government's financial resources, so that the social housing policy can be steadily promoted.

[1]: Japan's social housing occupancy standard is 25% of the income score, and Hong Kong's occupancy standard is about below 30% of the income score.

[2]: Comparing the experience of Taiwan and South Korea can highlight this missed price. The two sides also had a housing movement in the late 1980s. At that time, South Korea's economic development and GDP performance were not as good as Taiwan's, but they decided to start building social housing, while Taiwan took more than 30 years to start.

[3]: According to the French "Housing Dictionary", social mixing refers to: through housing projects, people of different social classes can live together in the same urban unit, which is the ultimate goal of various social policies.

[4]: In 2019, Xingtian Temple, Bandung Station and Dunhuang social residences all adjusted rents according to the surrounding market conditions. The three-bedroom social residences in Bandung with the highest increase increased by about 24%.

[5]: Taking New York as an example, the development forms and scales of residential buildings in different areas are designated through regional rezoning. Generally, in areas where high-density development is allowed, developers are required to cooperate with the construction of a certain number of affordable housing, and give floor area ratio incentives and rents. tax relief. Initially, inclusive zoning was introduced only on the island of Manhattan, and has since been adopted in other boroughs. After taking office, the current mayor, Bill de Blasio, proposed the "2014-2024 Residential Ten-Year Plan" to further strengthen this approach.

[6]: South Korean urban redevelopment plans must provide 17% (20% in Seoul) of the volume as social housing, and the government provides volume incentives as land fees, and purchases social housing at "cost price". A total of 55,103 households have been acquired by the city of Seoul through this model. (Statistics to 2014.04)

[7]: See Article 3 of the “ Measures for the Distribution and Utilization of Income Taxes under the Integration of Real Estate and Lands ”.

[8]: Quoted from Taipei City Lands Bureau, He Shenzhu, "Uncovering the Mystery of Substantial Tax Rates", Table 2 "Comparison of Real Property Ownership Tax Substantial Tax Rates in Various Countries".

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More