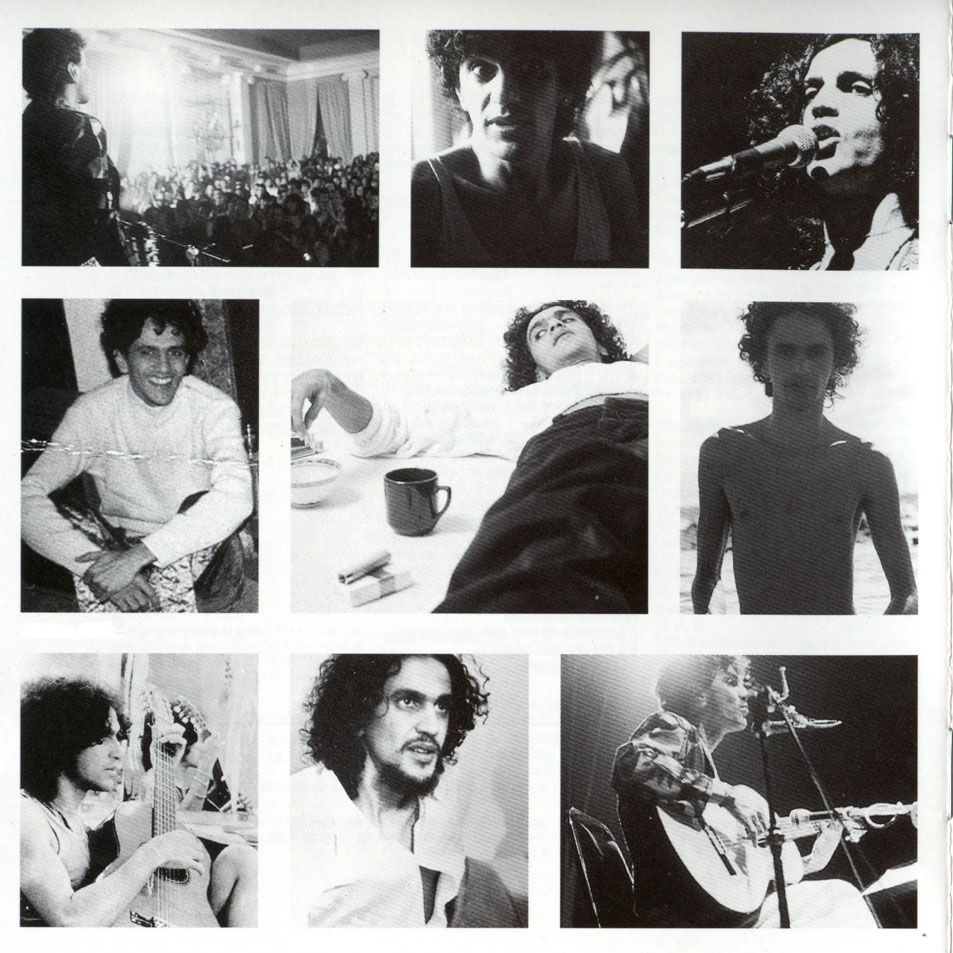

譯書寫字的人,住處毗鄰加州伯克利大學,身在學院外。識得粵國英三語,略知法文。因癡迷巴西音樂,四十歲後始習葡萄牙語,宏願是將Caetano Veloso的回憶錄翻譯成中文。

Hear Brazil, Translator Cayetano (Part 2)

[English] Text by John Ryle / Translated by Zheng Yuantao

John Ryle is an anthropologist, professor, author, and translator at Bard College, New York, USA, living in London. This article was previously published in Granta magazine, and the Chinese translation was first published in "Single Read". The translation and minor changes are authorized by the author.

Encountering Brazilian Politics

[Continued (middle)] With the guidance of Cayetano's songs, my initial understanding of Brazil has deepened. Those songs reflect every aspect of national life - politics, culture, history, regional spirit. He writes himself in the terroir, in the heart of the country: El Salvador, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo – the songs Cayetano wrote for these cities are among his most famous and become the collective memory of Brazilians. Listening to them is like hearing The Beatles for the first time in England, or Bob Dylan for the first time in America.

Later, when I returned to England, I found myself still obsessed with Brazilian music and my interest in the incredible rituals of the Brazilian religion of African origin. In the 1980s, when vinyl gradually gave way to CDs, I frequently returned to Brazil, and every time I went back to China, I would definitely add a lot of new records to my luggage, and my understanding of the content of singing became more and more clear. stand up.

My Brazilian friends see the incident as a joke - they're used to the corruption of their country's politicians. But some friends advised me to be prudent and not to come to Brazil for the time being. They reminded that President Colroll's father, also in politics, shot and killed a political opponent in the Senate, but used a trick to use senatorial privileges to save his congressional seat without going to jail.

Eighteen months have passed. President Colroll's malfeasance was well documented and involved more than I and most people could imagine. Brazil's Veja magazine published a lengthy interview with President Collor's own brother, detailing his brother's poor morals and the shocking inside story of the authorities' fiscal corruption. At this time, the Brazilians, who have been used to seeing politicians stealing the country for many years, felt unbearable. Soon after, Colroll, who was facing impeachment, resigned and was ruled not to hold public office for eight years.

It was another year or two before I returned to Bahia. At this time, I was shown a text from El Salvador's largest newspaper, A Tarde, which I read to my satisfaction. It reads:

Does anyone still remember John Ryle? Let us help you relive an old memory: He was the first journalist to make real accusations against former President Collor de Mello. The British newspaper that published the article paid a hefty fine for it. Shouldn't the Brazilian government be returning the money now as a matter of justice?

As far as I know, the Sunday Times never asked for that money back, nor did it report the fall of President Collor. I haven't written for them since.

Before I had the chance to return to Brazil, Pierre Figger, French photographer and ethnologist, my former spiritual teacher and host of residence, died in El Salvador at the age of ninety-three. In London, I sat down to write about his life. I reopened the Cayetano translation that I did a few years ago. Facing the blank screen, I imagined myself in El Salvador in the 1940s, when Feige was a newcomer from France and Cayetano was growing up in the small hinterland of San Amaro. From a fan site, I downloaded the Portuguese lyrics for "The Miracle of the People," which I first heard at the Anglo-American Hotel many years ago. I started over to translate it into English.

The second of the two verses from "The Miracle of the People" reads: "Obá é no xaréu / Que brilha prata luz no céu…"

Obá é no xaréu Que brilha a prata luz do céu E o povo negro entendeu Que o grande vencedor Se ergue além da dor Tudo chegou sobrevivente num navio Quem descobriu o Brasil Foi o negro que viu A crueldade bem de frente e ainda produziu milagres De fé no extremo ocidente Quemé ateu? Auba's spirit in the sea fishes when the sky shines with silver scales and the black people know that the great victors will rise in hardships Here everything comes from the slave ships that survived The discoverers of Brazil are black people who see before them cruel and still created the miracle of faith in this far west Who is an atheist?

Quem é ateu? The last line of the Cayetano song returns to the first, but this time with a rhetorical question: who can really be an atheist? He was asking: When you draw inspiration from a culture of faith, then in what sense can you be called an atheist? It can be seen that Cayetano's thoughtful thinking makes pantheism and reason dance together. In order to deepen my understanding, I have to write a written translation. So I was drawn back to Cayetano's earlier songs, and then translated the works of other Brazilian poets and singers, including the aforementioned Vinicius de Morais, and Carlos Drummon. Carlos Drummond de Andrade, João Cabral de Melo Neto.

Translation work

Not long after, towards the end of 2000, at a party hosted by my London neighbors Melissa North and Zac Chassey, I met Cayetano again: still the skinny Elegant figure, neatly dressed, black suit buttoned up high, hair now a little gray. He was accompanied by his wife Paula Lavigne. I learned from our conversation that Paula had recently finished a documentary on Pierre Fage, which included Fage's last interview, and he died the day after the filming.

I mentioned my translation of "The Miracle of the People". A few days later, at Cayetano's request, a translation was emailed to him. Also at the end of the year, he wrote to me asking if I would be interested in translating the lyrics for the US version of his new album Noites do norte.

Some music critics in Brazil gave "Nights of the North" a moderate evaluation, but I appreciate the mellow feeling of Cayetano's maturity in it. In this way, I relive the joy of his music, and go upstream, to swim in the cultural history of Brazil. Many of the songs on the album were born in El Salvador's cultural mix with African and European elements, and were born out of the legacy of slavery. The name "Nights of the North" itself is a work of the nineteenth-century Brazilian abolitionist leader Joaquim Nabuco. With the symphony accompaniment of the album's title song, Cayetano sings an astonishing phrase written by Nabucco like a recitative:

A escravidão permanecerá por muito tempo como a característica nacional do Brasil. Ela espalhou por nossas vastas solidões uma grande suavidade; fosse uma religião natural e viva, com os seus mitos, suas legendas, seus encantamentos; insuflou-lhe sua alma infantil, suas tristezas sem pesar, suas lágrimas sem amargor, seu silêncio sem concentração, suas alegrias sem causa, sua felicidade sem dia ...É ela o suspiro indefinível que exalam ao luar as nossas noites do norte. Slavery will remain a national feature of Brazil for a long time to come. It spreads a great softness into our vast solitude; it leaves its first imprint on our virgin ground, and it remains long; it spreads here as if it were a natural and incessant religion, with its own myths, Legends, wonders; it breathes, breathes out its childish spirit on the earth, it does not have heavy sorrow, tears without resentment, unfocused silence, joy without reason, don't care about tomorrow's happiness... it It is our indefinable but faintly audible sigh in the northern night when the bright moon shines brightly.

Like "The Miracle of the People," this passage contains a delicately balanced sentiment that acknowledges (but does not endorse) the profound and lasting effects of slavery on the Brazilian nation. As someone who has written songs in both English and Italian, and translated the English lyrics into Portuguese, Cayetano took great pains to convey the passage accurately in the translation. He cared even more than caring about how his lyrics were translated, and offered countless suggestions for improvement. In London's winter, I would get up in the dark mornings, work on this song and the rest of the album, and email the translation to Bahia in midsummer, five thousand miles away. He will reply quickly, discuss some details of the translation, and accept the rest.

The new album is not only about Brazil's past, but also some purely lyrical songs. In "I Am Your Song Thrush" (Sou seu sabiá), the staccato rhythm in the last few lines of each passage simulates the cry of Brazil's national bird, the red-breasted sabiá.

Sou seu sabiá Não importa onde for Vou te catar Te vou cantar Te vou, te vou, te dou, te dar I'm your songbird. No matter where you go, I'm going to find you. I'm going to sing for you.

It is a joy to hear this voice again. For me, Cayetano has become the embodiment of Portuguese charm. I think of the mornings I spent many years ago at the Anglo-American Hotel, when I was naive and full of yearning, my love for this country not yet tempered by my own experience—the storm of being caught up in Brazilian politics—when all I could do was dream Step into the Portuguese-speaking world, let the flames of Pentecost come, and refine my speaking ability.

The miracle of Pentecost

The miracle of Pentecost, in a sense, does happen, although it is not a tongue of fire from heaven, but more like a red fire, a slow-burning thing, a little bit by the breath, by the speech itself Be cooked until it has enough light to shine on you and find your way in a new language. Translating Cayetano is an opportunity to rekindle this light, so that I can revive the memory of that city, that country, that language incarnate in him, so that I can relive the fascination of El Salvador many years ago. Feeling: Watching the boys of Badauai and the girls of Kuruzu roaming the streets in the twilight, the call of love is the voice of the city at this moment.

That's what Cayetano himself took years ago, when he explored the idea of translation in a song called "Trilhos Urbanos." The song sings to the street corners and tram tracks, and the lines of lyrics all lead to the past time and the urban style of childhood. In the song, the act of translation becomes a metaphor for memory itself, a metaphor for redemption of the past.

Sitting at a desk on a cold, dark morning in winter, "Nights of the North" blaring on the stereo, and the rumbling of the Hammersmith and City train coming from afar, the lyrics seem fitting:

Bonde da Trilhos Urbanos Vão passando os anos E eu não te perdi, Meu trabalho e te traduzir Streetcars on city rails gallop away as time goes by and I haven't lost you My job is to translate you

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…