90後港仔,文字工作者,哲學愛好者,現正為哲學新媒體撰寫專欄。熱愛分享、評論好書及電影,偶爾會寫小說。

[Book Review]: In the age of images, the lost sympathy

Originally published in Philosophy New Media

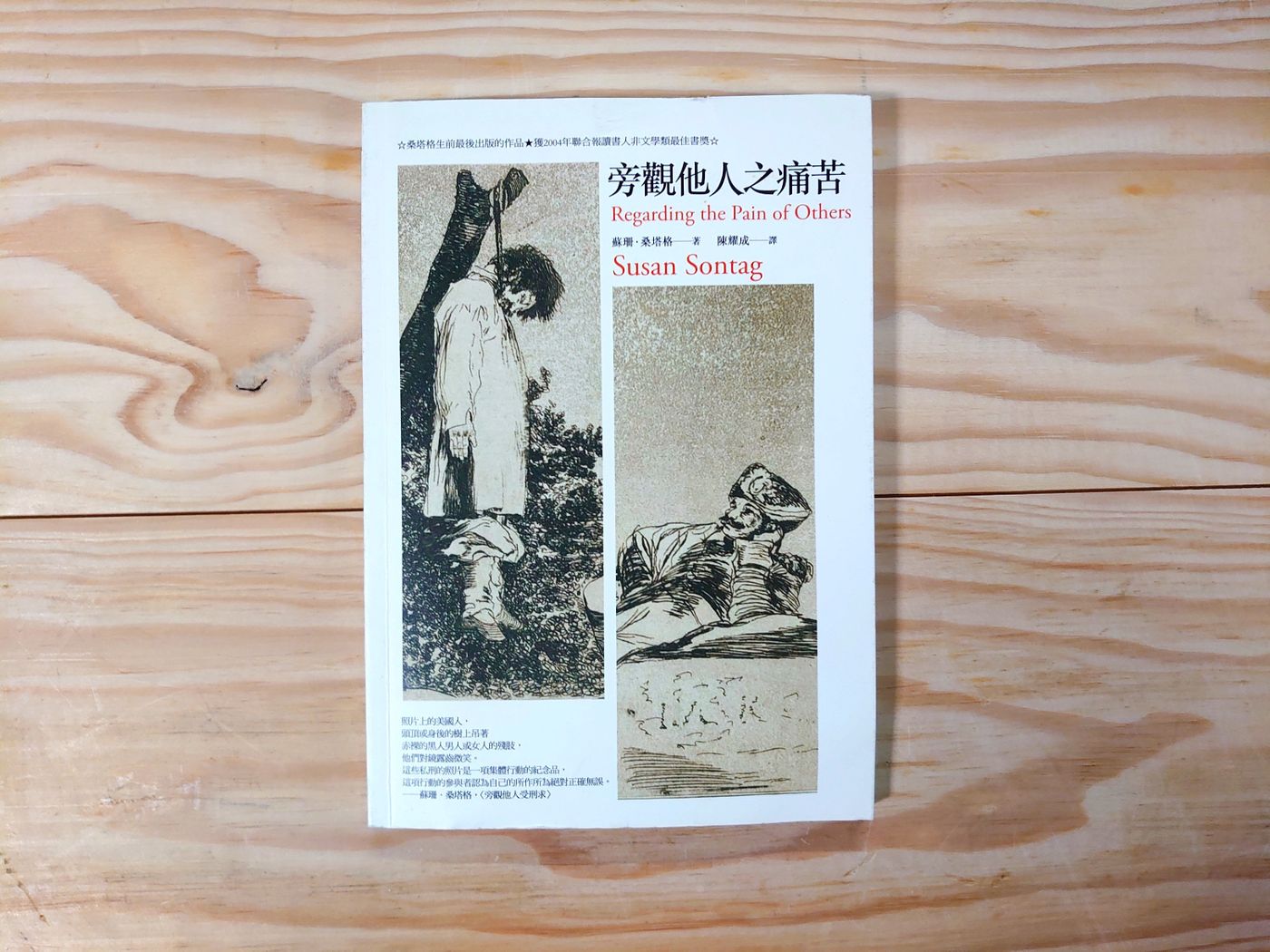

When the media reports on suffering such as war disasters, most of us, as viewers, express sympathy for the suffering of the victims, but after the report is over, our sympathy will quickly fade away, and we will continue to live as if nothing has happened. But if someone is suffering in front of us, we will somehow step up to help and relieve the other person's urge to suffer. Why do we tend to "stand by and watch" when looking at the world through the lens, and are indifferent to what other people experience? Can't we just watch the suffering of others? So how is it ethical to watch? Susan Sontag reflects on the pain of watching others through Regarding the Pain of Others .

The distance between image and reality

During the Spanish Civil War, a lawyer wrote to the British writer Virginia Woolf , asking, "In your opinion, how do we stop the war?" "We" were unique to Sontag. Meaning: "We, the subject, must never be taken for granted when looking at the suffering of others." 1 First, "we" refers to the fact that as human beings, when viewing photos/images showing the suffering of others, each person reacts differently , this difference comes from the gap between the lens and reality.

Generally, our intuition is that photos represent "reality" "objectively". If you look at the photos in front of you with the suspicion of "what's missing from the lens", it is not difficult to find that photos or images involve many subjective choices. Photos and even images can distort reality as long as they are presented in a different order. The cutting of reality by the lens leads to a gap in space and time between the viewer and the viewer. The interception of a certain space and a certain period of time gives the possibility of open interpretation, just like a child in the fire of war, how the image of the body in a different place is appropriated by people with different political opinions, or even reused, and they each explain it. 2

The reality is different depending on the angle chosen, and because as a person experiencing the event, or a bystander watching the video, there is a gap in the experience. The French philosopher Bouzier once stated: "The Persian Gulf War never happened", which means that the Persian Gulf War is a media-oriented war: the victims affected by the war in the Persian Gulf, the reality in their eyes is blood and flesh and blood. However, Americans thousands of kilometers away are only shaped by media images, making the war only a show of military strength, not only its cruelty has been reduced a lot, but the real suffering caused by the war has also been covered up. Difficult to attack the government.

All images are Jinghou text misinterpretation. 3

When the picture is extracted independently, it is like viewing a painting: how to see it is mostly affected by our experience, values, and judgment of good and evil. Sontag gave a paradoxical example: when the images documenting the disasters of the two countries were displayed side by side in a photography exhibition at the same time, they were protested by the citizens of one country, because this act was tantamount to comparing their own experiences with those of other countries. Disasters, in comparison, diminish the "uniqueness" of their experiences. The background differences between viewers, even if they are people with similar experiences, also make it difficult to consistently feel compassion for the people in the images. 4 Since the photos are open and can elicit divergent reactions, Sontag asked: How can we return to our human identity to understand the pain of others among the many reactions and feelings?

Bystanders and exploits the pain of others

Through the medium of photography, modern life offers countless opportunities to be watched and exploited—the suffering of others. 5

Sontag points out that we are born with a penchant for watching others suffer. In an era dominated by consumption, photos are used as commodities. The more violent they are, the more conspicuous they are, in exchange for higher click-through rates and advertising fees. The suffering of others has gradually become our consumer goods. Sontag cites an example: a photograph of a soldier's death on July 12, 1937, in a magazine called Life, which took up a full page on the right, with men's merchandise on the left. full page of ads. Magazines do this to attract readers' attention6 . Like the movie " Nightcrawler ," where the male lead sells first-hand live footage to news organizations for a living. In order to sell his clips at a good price, he risked himself to capture first-hand scenes of accidents, bloodshed, and even gang gun killings. With his hard work and anti-social personality, he quickly moved up the society step by step from an unknown thief. The magazine's approach and the male protagonist in the movie confirm that there are bloody scenes before ratings, or, conversely, because there are audiences who like to watch bloody movies/images, these pictures and images become marketable.

The images captured by the media are premised on sensationalism and drama, which in consumer culture is a guarantee of income. Unconsciously, our cognition of reality is also subject to the media reports; the disaster constructed by the media is full of image symbols, and there is still a distance between the real picture and the reality. Taking the September 11 attacks in the United States as an example in the book, the people in front of the TV watched the plane crash in the World Trade Center. The news reported the scene was so immediate and "real", but for the people at the scene, the experience of this disaster was But it was like a dream.

Sontag believes that no matter how the camera frames the disaster scene, the situation in the image is a very real experience for those who actually experience suffering. In the face of the above-mentioned constraints (including the gap between reality and the camera, the background difference between viewers, the nature of people who like to see other people's pain, and the distortion caused by the media and the audience in the consumer society), as a viewer. The reader can only stay alert all the time and see through the selection results presented on the screen. Only by looking at those who are suffering and returning to the judgment of being a human can we truly face the pain of those involved. This touches on the central idea of the book: As a viewer, how much time can you devote to feeling the pain of others?

Limitation of Liability

However, it is not easy to truly understand the pain of others. Have you ever had the following experience: The image in front of you is really painful to watch? Or do you simply ignore and turn a blind eye to the inability to change the reality you see?

Whether it is the fear of the former or the indifference of the latter, it all stems from a sense of helplessness and powerlessness that cannot be changed in reality.

The so-called "cold feeling" means "the paralyzed state of emotional and moral perception is actually full of indignation and frustration." 7

A single photo is limited in what it can say. It cannot state arguments like words; the moment presented in the picture can only invite others to pay attention, reflect, and trace the ins and outs of the incident through the sensation of the picture. An image can not only be a record, it can also contain an indictment, for example (a picture of Hong Kong police using violence against young students) and a photo of police brutality is meant to point out the regime's inhumanity.

Compassion is only the first spark that images can provide. When there is no action, when the spark is exhausted, only indifference remains. In other words, when we look at images and feel pity, but "do nothing", it's another kind of detachment: I pity what happened to you, and that's all.

So what does Sontag mean by "action"? Does she demand that every time you look at a photo, you have to change the world?

Regarding the incident of African-American George Floyd , it is difficult for us in the Chinese region to imagine that before the start of a major Western football game (such as the Premier League), players will kneel on one knee to confront African-Americans. Floyd's incident expresses protest and dissatisfaction. What happened in the United States, what obligation do we have to make a statement for the people of that country?

However, despite the Floyd incident in the United States, there was a similar act of solidarity in the United Kingdom, and that is because the issue of race is an important issue in the Western world, not just in the United States.

As mentioned above, the distance between the image created by the lens and the reality, as well as the identity gap between people, will directly affect our connection with the misery of others. To some extent, these factors, in turn, reduce our responsibility to change the status quo for each other.

How is it ethical to watch?

So, in the Chinese world, we know the conflicts on the other side of the world through the lens, how should we deal with ourselves? Sontag reminds us that while there is no duty to change the status quo, it does not mean there is a right to disregard. The only thing we can do is pay attention and reflect on the suffering of others. To do this, we must move from pity to sympathy.

The difference between pity and sympathy is that in the face of the suffering of others, do we put ourselves in the position of the suffering person and experience the suffering of this person with our hearts; or do we pat the person on the shoulder after listening to what the person has experienced? Said: I feel sorry for what happened to you, and then walked away. The former, which is sympathy, requires one’s imagination and the input of one’s own experience, so as to be sad with the other party; the latter, which belongs to compassion, is cheap. Being a listener doesn't really feel sad or even condescending for the narrator.

Do we feel uneasy when others speak of pain and want to end the pain of the other person? The moral value of reflecting on the suffering of others is the recognition that we are all human beings, connected by our commonalities. The flip side of this connection is the realization that being able to watch from a safe distance is driven by luck, but rather by Moral arbitrariness. Our background, status, skin color, health status are not something we can choose, everything happens by chance. Since the suffering people cannot choose their birthplace, it is also a coincidence that they were born in the disaster. This cognition places us on an equal footing with the person being watched.

When the pain of others is exploited, whether it is for money or political propaganda, through the filter of the media, the victim gradually becomes a means to achieve certain goals, rather than being treated as a human being.

If attention and reflection are, for Sontag, the equivalent of action, then condemnation of exploiting the suffering of others, terminating their status as "objects for others to see", can reawaken the masses, victims like us, Treat the viewing other as a subject rather than a means to an end.

Epilogue

As long as the lens exists, there will be a gap between the viewer and the person being watched that cannot be fully understood. Since the lens only presents part of the truth, the viewer cannot fully grasp the pain of the person in the image. The position of the "viewer" is destined to create an uneasy tension within us, oscillating between a sense of inaction and helplessness. Although unable to get rid of the position of the bystander, Sontag pointed out that the withdrawal of the bystander frees up space for us to think about the suffering of others8 ; to reflect on the emotions caused by watching, and to regain our empathy for people.

We live in a cross-current of images, unknowingly experiencing the emotions Sontag raised above on a daily basis. Her thinking seems to continually tune our sensitivity to the pain of others, to find the right frequency of connection with the person being watched, without numbing us with a sense of powerlessness.

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…