文化批评研究 电影研究 现代及后现代艺术 性别问题

Uninvited Guests: Soviet Jews in West Berlin (1974-1975)

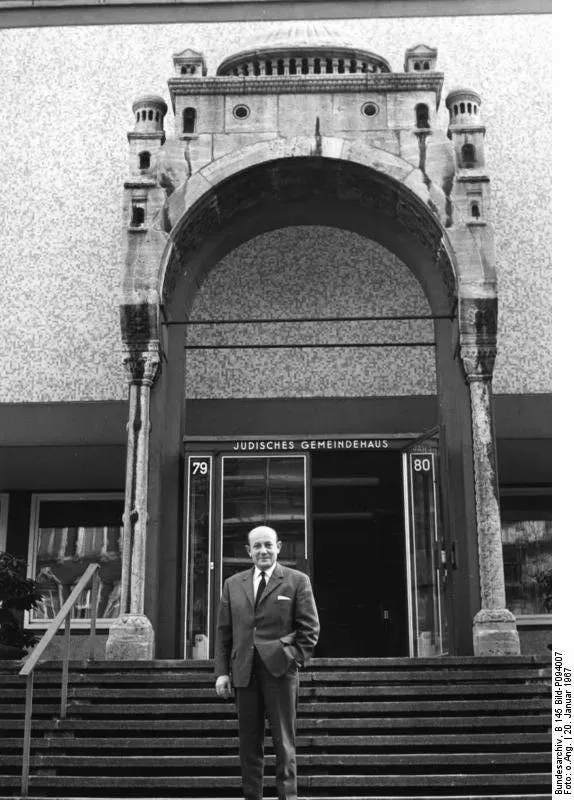

【Abstract】In 1974, more than 500 Soviet Jews unexpectedly appeared in West Berlin, causing local, national and even international reactions. These migrants left the Soviet Union with permission to travel to Israel, or to refugee camps in Vienna and Rome to West Berlin. They claim to have chosen a free new home and intend to apply for citizenship immediately. Due to the history of Nazi Germany, the West Berlin and West German governments, although not ready to welcome or expel them, instituted some temporary measures to encourage more Soviet Jews to arrive, compounding the difficulty of receiving them. Given the peculiarities of German history, the governments of West Berlin and West Germany, although not ready to welcome or expel them, also formulated expedient measures, which prompted more Soviet Jews to come to Germany and aggravated the reception difficulties for the German side. (The picture above shows the Jewish community in Berlin)

Uninvited Guests: Soviet Jews in West Berlin (1974-1975)

The Unexpected Arrivals: Soviet Jews in West Berlin 1974–75

By Carole Fink (The Ohio State University History Department)

Translator: Chen *gang

Citation: Fink, C. (2021). The Unexpected Arrivals: Soviet Jews in West Berlin 1974-75. International History Review, 43(3), 475-487.

On November 11, 1974, the West German news magazine Der Spiegel published a shocking report that more than 500 Soviet Jews were currently being held in the Marienfelde refugee camp in West Berlin. . The walled city is still mired in the 1973 oil crisis and the stagflation that followed. By this time Berlin had become home to some 200,000 Turkish, Greek and Yugoslav workers and their families, as well as tens of thousands of refugees from Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Now, it needs to face the test again from stateless Jews from the Soviet Union, mostly illegal immigrants.

These uninvited guests were also the vanguard of the thousands of Soviet Jews who entered the Federal Republic of Germany around the 1990s, but their stories are largely unknown. In addition to filling in the gaps in history, this article is a study of immigration that links Cold War, Jewish, and German histories. It delves into the international context of Soviet Jewish immigration and details the claims of Soviet Jewish Pairs. The main focus of this article is West Germany's response when the arrival of Soviet Jews provoked a complex diplomatic and domestic situation, including the mobilization of West German Jewish leaders and the memory of a not yet gone Nazi past.

leave the soviet

In December 1966, the head of the Soviet Council of Ministers, Alexei Kosygin, stated that they wanted to ease relations with the West, and suddenly announced that Jews in the Soviet Union had the right to leave to be reunited with their families in Israel. However, after the "Arab-Israeli War" in June 1967, Moscow pursued a capricious permit/restriction policy. In 1968, 231 Jews were allowed to immigrate, rising to nearly 35,000 in 1973, but then dropping to 13,000 in 1975. At the same time, as the number of applications increased, so did official refusals and protests by those who were rejected.

By the late 1960s, the struggle for Soviet Jews to leave their homeland had grown into an international human rights movement led by the American Jewish community and strongly supported by Israel. After 1969, increasingly de-escalating relations involved the U.S. government. Despite the Nixon administration's reluctance to push the matter, strong anti-Soviet sentiment still pervades American politics and society, forcing Congress to act. In 1974, the Jackson-Vanik amendment linked U.S. trade concessions to increased immigration of Soviet Jews.

The Soviet leadership was disgusted by outside interference in its internal affairs. In 1974, the Kremlin, benefiting from its growing oil and gas revenues, stopped demanding economic concessions from the United States or seeking to pay for détente. In 1975, the Soviet Union rejected a proposal by U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko to set an immigration quota of about 60,000 Soviet Jews per year and rejected trade agreement with Washington.

Soviet Jews advocate free choice

Before 1974, almost all of the 84,000 Soviet Jews who left the Soviet Union immigrated to Israel. The Israeli government provided indispensable documentation for their departure. Workers from Israeli-funded Jewish agencies run the Schönau refugee camp outside Vienna, where they check in before flying to their next stop in Israel, and the U.S. government has funded the resettlement of these Jews.

However, by 1974, 2,500 Soviet Jews had left Israel again, some for a few years, some for only a few months. Their reasons included poor job prospects, inadequate housing, language problems, military service for both men and women, discrimination against mixed-race marriages, extreme heat, difficulty adjusting to Israel's customs, and the tense political and economic environment created by the October 1973 war.

Although their numbers were small, those who left caused an uproar. The Israeli government, the press, and the public all derided them as "yordim" (roughly, the exiles eliminated by Israel). Israel has complicated procedures for them to go abroad, including the need to repay loans. The Israeli government has also pressured two major Jewish organizations in the United States, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) and the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee of America (JDC), not to provide aid to those leaving the country, forcing them to send to smaller groups. , underfunded Jewish and non-Jewish institutions for help. At this time, the United States, under pressure from the leaders of the American Jewish community, instituted special procedures to admit them.

The second category of "defectors" was the "noshrim," meaning those who left behind, those Soviet Jews who left the Soviet Union with Israeli documents but decided not to go to Israel. At the end of 1973, Palestinian armed forces captured five Soviet Jewish immigrants on a train bound for Vienna. The Austrian government ignored Israeli protests and imprisoned them in the Schönau refugee camp, citing serious security concerns. This practice made possible later similar practices. Housed in facilities run by the Red Cross, Soviet Jews, aware of the difficult conditions in Israel and the plight of "defectors", intended to choose a free destination. Despite the efforts of the Israeli government and the pleas of Jewish agency officials in Vienna, the number of "Noshrim" rose sharply from 1,372 in 1973 to 4,745 in 1975.

The Israeli government and people accused these "Noshrims" of being opportunists and traitors. Most of these people intend to immigrate to the United States because of its relaxed entry rules and greater career opportunities, and they have strong support from Jewish Aid in the United States, which supports Jews in making free choices and is organized by Emerging facilities supported by the U.S. government are staffed. There, their transit time can be as long as five months.

Arrive in West Berlin

On November 11, 1974, Der Spiegel published its first report on the matter. But the year before that, more than a hundred Soviet Jews had come to West Berlin, and their numbers were steadily rising. Why did they choose this city? On the face of it, this is an unlikely destination, an isolated, self-splitting "Cold War" enclave that was once the capital of the Nazi Empire, whose war crimes touched almost every Soviet Jewish family.

However, the emergence of "Ostpolitik" (Ostpolitik, West Germany's policy to normalize relations with Eastern Europe) in 1969, especially Prime Minister Willy Brandt's "Warsaw Warsaw" in December 1970 in front of the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Kneeling" (Warschauer Kniefall), which greatly enhanced the image of West Germany in the communist world. In addition, the "Oriental Policy" loosened the barriers for Soviet immigration to Germany and facilitated the rebuilding of personal, family and professional relations between Soviet Jews and West Germany.

West Berlin has several advantages. Since there are no visa requirements for tourists with Israeli documents, the "Noshrims" (who constituted the majority of the first arrivals) were able to go directly there without resorting to Jewish or non-Jewish aid agencies. Furthermore, despite the economic downturn, the SPD-led government in West Berlin is known for its welcoming of refugees and generous welfare benefits. And, the city of nearly 2 million residents has become an important cultural, intellectual and industrial center, with relatively affordable housing, extensive federal subsidies, and immunity from federal military service.

Equally important, West Berlin is home to Germany's largest Jewish community. The community, which has about 5,500 members, is led by energetic Holocaust survivor Heinz Galinski, who has also played an important role in two major national Jewish organizations, as director of the German Jewish Central The Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland (Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland) and the German Jewish Central Welfare Agency (Zentralwohlfahrtsstelle der Juden in Deutschland), which coordinates Jewish philanthropy and distributes federal aid. A formidable negotiator and fundraiser, Grinski wrote regularly for the local and national media, serving as a moral authority, reminding the West German public of its responsibilities to its fellow Jewish people.

Admittedly, life in West Berlin carries certain risks. The presence of thousands of Palestinian refugees, combined with the opening of the PLO office in East Berlin in 1973, has increased the sense of danger for the Jewish community in West Berlin. In addition, the city's strained economy and growing local dissatisfaction with foreign workers and asylum seekers pose potential obstacles. Still, for those who chose this Cold War island in the early 1970s, West Berlin represented not only an escape from Soviet policy, but also an accessible and relatively hospitable place to settle.

As of December 3, 1974, there were approximately 529 Soviet Jews in West Berlin, 499 of whom were from Israel. Some early arrivals were generously welcomed by the local government, but instead of registering with the community, they found housing and jobs on their own, disappearing directly into the urban population.

Thanks to the records of the German Jewish Central Welfare Agency, which provides assistance to more than a third of arrivals, we gain some insight into this extremely diverse group. Among the arrivals from Israel, the ages ranged from 17 to 72, and most were between 33 and 55. Most of them were born in the Soviet border areas annexed after World War II, which were formerly home to large numbers of Germans and Jews (notably Riga, Latvia and northern Bukovina), although a small number were born in Kyiv, Minsk and Moscow.

The length of stay of these Jews in Israel varied from a few months to six years, with an average of one to three years. About two-thirds were married, and more than half of them came with their children. Immigrants in need of assistance work in various occupations, but are mostly skilled workers (locksmiths, shoemakers, plumbers, tailors, cooks, butchers, carpenters and electricians), although there are also a few professionals (teachers, lawyers, civil engineers) and some older musicians Family. Far fewer came directly from Vienna, ranging in age from 20 to 67. Most were married and came with their children, and there were slightly more professionals than artisans. Although a few came from important cities in the heartland of the Soviet Union, they were mainly from the Baltic states.

West German law divides immigrants into two categories: those of German descent, who are entitled to immediate citizenship, and foreigners (Ausländer), including guest workers (Gastarbeiter), refugees and asylum seekers, who are There are significant barriers to obtaining permanent residency and citizenship. Most Soviet Jews who arrived in West Berlin intended to apply for immediate German citizenship based on their historical ties to German language and culture.

The legal basis for this is the Federal Deportees Act 1953 (Bundesvertriebenengesetz, BVFG). The law would have initially granted citizenship to the millions of Germans who were expelled from Eastern Europe after 1945, before extending to those who later fled during the "Cold War". The Federal Deportees Act contains a very subjective definition of national identity, which is based on the applicant's self-identification (Bekenntnis) with the German National Community of his home country.

But while the Federal Deportees Act does not exclude Jews, it requires a clear public commitment confirmed by witnesses. The responsibility for implementing the Federal Evictions Act rests with state officials, who decide whether to issue the prized deportee card (Vertriebenenausweis), which grants immediate citizenship, free German language instruction, and benefits in housing, work, and including unemployment insurance. Priority is given to social services within the country.

However, a large number of applications from Soviet Jews produced mixed results. Greenski received grants from the local government to help these people, and he assigned a social worker to Marinefield to help with the paperwork. But the initial decision by the West Berlin authorities was discouraging. Between 1973 and 1974, only 200 of 549 applications were approved. Even under the subjective criteria of the Federal Deportees Act, there were serious obstacles to proving German identity, especially since the applicants had previously immigrated to Israel and their Soviet documents appeared with the designation "Jewish" and no longer Is a member of the German National Community and cannot immediately obtain citizenship.

The rejected Soviet Jews were in a dangerous situation. Those who come from Israel cannot describe themselves as refugees fleeing persecution, war or violence. Holders of an Israeli passport (those who have been in the country for more than three years) can stay for up to six months. And those who stayed in Israel for a shorter period of time came with a pass and a special approval from the West German embassy (visa, Sichtvermerk), leaving a non-refundable deposit. The situation is even more uncertain for those who do not have any German ethnic identity and are undocumented. According to West German law, these people are illegal immigrants, unless the local government can make an exception, or will be deported.

West Berlin's response

An article in West Germany's Der Spiegel in November 1974 brought attention to two important public issues: the housing crisis in West Berlin and security threats. After Marinefield was filled, newly arrived Jews were placed in the city's Red Cross Center, where overcrowded conditions drew negative comments from neighbors and local media. Moreover, given the situation in the Schönau refugee camp, the West Berlin government was afraid of creating a "ghetto" and a "terrorist attack".

Even more pressing is the negative ruling by the local government on the immigrant's personal status. Until mid-1974, the West Berlin senator for labor and social issues made a particularly lenient decision on applications for deportee passes, but now fewer and fewer newcomers are eligible. Nonetheless, given its "anti-Semitic" history, the West Berlin government has been reluctant to deport illegal Jewish immigrants, including those arriving directly from Vienna without documents or from Israel without valid visas. In fact, some city officials are prepared to make exceptions for "those who are willing to integrate into society" (integrationsbereite Menschen) and contribute to the "population balance" (Bevölkerungsbilanz) of the city.

Faced with an issue of international and domestic significance, the ruling SPD mayor of West Berlin, Klaus Schütz, turned to Bonn for advice. Schutz asked the foreign ministry to determine the Israeli government's views on the deportation and the interior ministry to identify conditions that could be exceptions, while suspending all local review processes for four weeks and ordering an investigation into conditions at the refugee center.

The German Foreign Office favored the generous treatment of Soviet Jews, strongly opposed deportations on humanitarian grounds, and had no fear of diplomatic repercussions. Foreign ministry officials expected little reaction from the Soviet Union and Arab countries to their green light to the Jews. In addition, the Israeli side has not made a clear response.

To be sure, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs acknowledges that the final decision to grant the exception rests with the state government, which must be in accordance with the country's current laws and taking into account current political and social factors. The Foreign Office also acknowledged that such a decision would undoubtedly increase the number of migrants. In addition, the number of immigrants in the future cannot be predicted. The Kissinger-Gromiko deal has yet to be rejected by the Kremlin, but it has the potential to significantly increase the influx of Soviet Jews and increase diplomatic risk. Furthermore, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs insisted that, from a historical, moral and humanitarian point of view, West Germany was obliged not to force Soviet Jews (even those who arrived illegally) to go to Israel or any other country.

The Home Office initially played a secondary role. However, in late 1974, when 10 Soviet Jews arrived in Cologne unexpectedly from Israel, it faced the task of coordinating policy in the 11 federal states (Länder). Therefore, on 9 December 1974, the Home Office issued an invitation (albeit with limited prospects) to convene an inter-ministerial meeting. In addition, Israel's reluctance to prevent Soviet Jews from leaving the country, and the Foreign Office's opposition to deportation, means that numbers may increase, with exceptions inevitably being decided by local governments.

German Jewish leaders intervened forcefully on behalf of Soviet Jews. During a meeting with Federal Interior Minister Werner Maihofer, two officials of the German Jewish Central Council, Werner Nachmann and Alexander Ginzburg, warned Bonn not to submit to Israeli restrictions in any way Entry demands, and insisted that Soviet Jews had freedom of choice. In talks with Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Nachman and Grimsky minimized the diplomatic impact of West Germany's "Duldung" policy.

In late October, facing the dismal prospect of deporting some 300 people, the West Berlin government also sent an ambassador to Tel Aviv. There, the West German ambassador promised to gather more information on applicants and issue visas more carefully, while the Israeli government agreed to address the illegal influx of Soviet Jews into Tel Aviv.

On December 3, 1974, the West German Senate unexpectedly announced that all Soviet Jews living in the city would be allowed to stay, with residence and work permits. But from the next day, all new arrivals will only be allowed to stay for a maximum of six months, unless they are eligible for visas permitted under the Federal Deportees Act.

Grinski claimed two key concessions were made in admitting relatives still in Israel and visiting relatives in West Berlin. And, with the resources of the local Jewish community already stretched thin, he urged the managing mayor Schutz to put pressure on other states to admit a corresponding number of Soviet Jews.

The public reaction has been mostly positive. The West German press, while noting the laxity of Berlin's policy, also endorsed the practice of "checking" illegal immigration. However, the Münchner Merkur newspaper called the Dec. 4 decision a shameful surrender to the bureaucracy in a "place of Jewish tragedy". In the Bundestag, there were questions, but no major objections. Outside Germany, the Israeli government also quietly agreed with West Berlin's statement.

Over the next year, West Berlin's stopgap quickly showed its inherent weaknesses. The influx of Soviet Jews continued, mostly illegally. But contrary to the prospect of the Kissinger-Gromiko agreement, the Kremlin, instead of sending Jews out of the Soviet Union at a rate of 60,000 a year, drastically reduced the number of permits, from nearly 21,000 in 1974 The number dropped to 13,000 in 1975.

Nonetheless, the number of Soviet Jews leaving Israel continued to rise. Soviet Jews wishing to remain in Europe, denied visas by France, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Switzerland due to their illegal legal status, continued to flock to West Berlin, with another 300 arriving by the end of the year.

In 1975, the demographics of the new arrivals in West Berlin did not change much. Their ages ranged from 25 to 78, with the largest group between the ages of 35 and 45, consisting mostly of married couples with children. They have been in Israel for 1 to 5 years and cover a variety of occupations, with professionals (engineers, teachers, economists, journalists and nurses) and an increasing number of truck drivers, mechanics, workers and retirees. Similar to immigrants from Israel, they were between the ages of 25 and 65, with the largest group between the ages of 35 and 45. There are almost equal numbers of singles and families, with more professionals than artisans, including dentists, artists and musicians.

West Berlin's strict policy on Soviet Jewish immigration quickly drew criticism at home and abroad. Greensky complained, both publicly and privately, that Berlin was reluctant to rush to deport illegal immigrants compared with its generosity to others, especially Palestinian refugees. To relieve the pressure on the city and the local Jewish community, Grinski and Nachman continued to urge West Berlin and the federal government to pursue a cautious and generous policy of sharing with other states.

But West Germany, facing inflation, rising unemployment, and two major "terror incidents" in 1975, was not ready to focus on the arrival of a small number of Soviet Jews. After the state interior minister rejected West Berlin's proposal to coordinate its policy (although recommending against deporting immigrants from Vienna and Rome, and taking a tougher stance on immigrants from Israel), the focus turned to the interior ministry. Interior Minister Maihofer launched an inconclusive investigation into illegal border crossings and urged the foreign ministry to impose stricter controls on visa issuance for Soviet Jews leaving Israel for West Germany.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs continued to oppose deportations and refused to put pressure on Israel to thwart those leaving the country. In fact, the diplomatic influence remains surprisingly modest, and there is no retaliation. Despite the Kremlin's "anti-Israel" propaganda mentioning the growing number of "defection" Jews, the influx of Jews into West Berlin doesn't seem to be much disturbed. Poland also continued to agree to release thousands of Germans (among them Jews), many of whom were also housed in Marinefield.

Israel faces a new wave of "terrorist attacks" and is under diplomatic pressure to reach an interim deal with Egypt and withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula, so they have no objection to the arrival of Soviet Jews in West Germany. In 1975, during two high-profile visits by Israeli Foreign Minister Yigal Allon and Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, both Israeli leaders hoped to be in the European Community, which was heavily reliant on Arab oil. Gained support from West Germany and became increasingly sympathetic to the demands of the Palestinian people. Rabin (the first native chancellor and first chancellor to visit West Germany) and his German-born wife, Leah Rabin, flew to West Berlin after a visit to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where Under high security, they toured the city and met with local Jews.

By the summer of 1975, West Berlin was again facing a crisis due to the growing number of Soviet Jews arriving in the city, a shortage of housing, and a growing possibility of eviction as local authorities faced more and more negative rulings on German citizenship. big. Compounding the West Berlin predicament, the Foreign Office continued to oppose deportations, the Interior Ministry was unable to win over other states to share the refugee burden, and Glinski kept making exceptions for Jews.

The city government's solution was to appoint a research committee, which, after listening to federal and Israeli officials, recommended quietly allowing all those who had arrived to stay. In October 1975, the West German Senate secretly passed another stopgap measure to give permanent resident status and work permits to those who arrived before November 18, 1975, who would be eligible for German citizenship within ten years identity. The Senate considered this special measure to promote "the healthy development of relations between Germans and Jews". However, the decision also contained an unrealistic restrictive clause that every effort should be made to persuade West Germany's diplomatic representatives (especially in Vienna and Rome) to limit the flow of "uncontrolled refugees" to West Berlin ".

Follow-up (1976-1980)

On August 1, 1975, following the signing of the Helsinki Accords, the number of Jews leaving the Soviet Union rose from 14,000 in 1976 to 5.1 in 1979, but fell to 21,000 in 1980. The Jewish community continues to receive annual subsidies for its work in Marinefield, and in response to Greensky's request, the local government reduced the wait time for citizenship to eight years.

However, the previously welcoming atmosphere has been greatly diminished. Those who submit applications face a growing number of negative rulings that an aging and exhausted Grinski cannot turn around. Additionally, sensational reports of human trafficking and fraud were linked to a group of Soviet Jews who arrived in Offenbach and several other small West German cities between 1972 and 1975, prompting West Berlin authorities to take a closer look at immigration Review.

Even more damaging, they uncovered an international forgery ring that was selling fake documents in Israel to those wishing to go to West Berlin. In 1976, 1,300 refugee documents were falsified, dozens of people were arrested, and hundreds of Soviet Jews were at risk of deportation. While West Berlin did not deport people with false documents, the incident led the authorities to decide that illegal immigration would no longer be tolerated. After September 22, 1980, only those Soviet Jews who arrived from Israel with valid passports and visas were eligible to apply for residency, although their families could be reunited with relatives in West Berlin.

After 1981, Soviet Jews continued to travel to West Berlin, but until 1989, the number of exit permits granted by Moscow dropped sharply and the number was much smaller. Moreover, to Grinski's chagrin, West Berlin authorities imposed stricter rules when granting exceptions. On the eve of German reunification in 1990, the West Berlin Jewish community had grown to 6,900 people, making it the largest community in West Germany.

Epilogue

Strictly speaking, Soviet Jews who arrived directly or indirectly in West Berlin in 1974-1975 were not refugees. Rather than being forced to leave their homeland, they chose to leave a place where life was difficult, even dangerous. To the extent possible, they decide where to settle.

Five international, national, and local factors influenced the arrival of Soviet Jews in West Berlin in 1974-1975 and their continued entry thereafter.

First, the arbitrary and often inconsistent decisions of the Soviet government on immigration; second, the role of Israel, both facilitating their exodus and failing to prevent their “defection”; the role of the Soviet Union and upholding their right to freedom of choice; fourth, the unique political, economic and demographic characteristics of their destination city, West Berlin; and finally, West Germany's special rules for admitting foreigners and Nazi Germany's past. effect.

Soviet Jews were illegal immigrants unless they could prove their German status; but as Jews, they were placed in a special category and required special consideration.

The unexpected arrival of Soviet Jews in West Berlin had a lasting impact on Jews and Germans alike. Although Soviet Jews were small in number and had few ties to Judaism, they undoubtedly contributed to the revival of Jewish life in West Berlin and West Germany. They mobilized Jewish leadership on their behalf and replenished aging communities depleted by death and immigration. According to one musician who entered West Berlin in 1981, they were "third wave" immigrants from the Soviet Union trying to create a new life in the heart of Europe.

For the West German government, the arrival of Soviet Jews raised diplomatic complications, divided local and national authorities, caused sensational press coverage, and produced inconsistent and controversial administrative decisions. There is no doubt that the federal and West Berlin governments gave special treatment to Soviet Jews, especially compared to their harsher treatment of Turkish laborers and refugees from Chile, Vietnam, and the Middle East. Those capricious but generally lenient decisions they made in the 1970s and 1980s were driven by atonement for the past, but perhaps also because of a shift in the discussion between the nation-state and the liberal state.

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…