文化批评研究 电影研究 现代及后现代艺术 性别问题

Wa State: A Copycat China in the Highlands of Myanmar

Wa State: A Copycat China in the Highlands of Myanmar

Der Wa Staat: Chinas Bergfestung im Hochland Burmas

By Hans Steinmüller (Department of Anthropology, LSE)

Translator: Yang Yuhao

Original: 2016. 'Der Wa Staat: Chinas Bergfestung im Hochland Burmas', Merkur - Deutsche Zeitschrift für europ?isches Denken 70: 807, 28-39.

Thanks to the author and translator for the contribution.

Wa State is an area in northeastern Myanmar that occupies an area comparable to Kunming City and is ruled by the local armed "United Wa State Army" . Its official status is part of the Union of Burma, but in fact the area is controlled by an independent local armed forces . The Burmese government and government forces have little influence on what happens in the Wa state. In many respects, the Wa state is closer to China, which borders it.

China watchers sometimes refer to the Wa state as "shanzhai China" . "Shanzhai" is a neologism in Chinese that refers to cheap imitations of branded goods. Such things are presumably made by poor and backward mountain people, and are used by those who cannot afford genuine products. In China's coastal provinces, you'll find the likes of knockoff "Nike" sneakers or knockoff "Gucci" handbags. Usually such products are slightly different from the real ones and are easy to distinguish, such as the mobile phone "iStone" that imitates the "iPhone", so imitation can also be understood as creative imitation [1].

Byung-Chul Han, a philosopher and media theorist in Karlsruhe, interprets the term as a concept that goes beyond the Western "original-imitation" dichotomy—it represents Chinese creative practices, where Rarely does originality play a role. Such a fundamental difference will quickly lead to the so-called "Orientalism" stereotype of the opposition between East and West: this stereotype often despises copying, thinking that "Chinese people like to copy." Even if this kind of imitation can be reinterpreted positively, the interpretation occurs in the discourse and relationship of inequality between East and West, so this interpretation is often an emotional and vague expression. The same is true for counterfeit goods, and the same is true for Wa State.

So when Chinese bloggers and journalists refer to a rebel territory in Myanmar as a “shanzhai China,” they first think of a cheap knockoff of the People’s Republic. And many things in the Wa state are indeed like dilapidated reflections of its huge neighboring country : Although the Wa people who speak their own language are the main residents of the Wa state (the Wa language belongs to the Austronesian language family and is completely different from Chinese), the Mandarin Chinese is still the same The lingua franca and official language of the region.

Administrative units and bureaucrats have Chinese names or titles, borrowed directly from their Chinese counterparts, such as secretaries, offices, ministers, and committees. Infrastructure, including electricity, water supply, and roads, is basically built by Chinese companies, and they usually send foremen from China. Mobile phone networks are built and operated by state-owned companies in China. The currency in circulation is RMB. Chinese companies also operate mining, rubber, tobacco growing, supermarkets and hotels. China provides financial and logistical support to the United Wa State Army that rules here. It is said that in addition to the old uniforms, there are helicopter gunships among the supporting materials, even though—or it should be said because of this— the Wa State armed forces are the most powerful of all ethnic minority rebels in Myanmar. [2]

So this "Shanzhai China" is not only a comical Chinese imitation, but also potentially dangerous.

The strength of the Wa State Army is attributable to its geopolitical position (i.e., a buffer zone between areas of Chinese and Burmese influence), opium production in the Golden Triangle, and armed conflict between various armies and guerrillas.

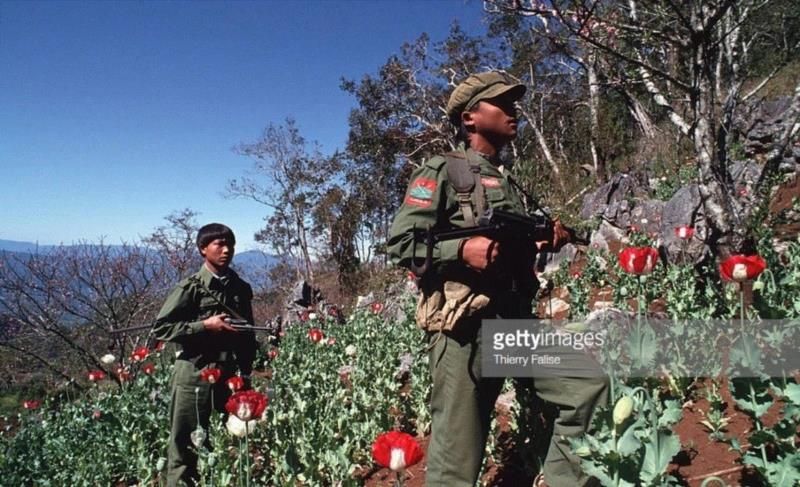

The predecessor of the Wa State Army was the guerrilla force of the Burmese Communist Party. In the 1960s and 1970s, it learned Mao Zedong's military theory taught by Chinese soldiers and volunteers. In addition to Chinese aid, local opium cultivation has been the main source of income for the Wa State Army for decades. Yet opium cultivation has been almost completely outlawed in the last decade, with China's longstanding pressure on the Wa Army playing a major role, in addition to the influence of the United Nations and NGOs.

Prohibition of drug production and circulation is a central means for the Wa State to gain recognition and legitimacy, as well as economic and military assistance. In order to replace opium poppies, Wa State has vigorously promoted cash crops such as tea, tobacco and rubber for two decades, and has focused on attracting investment, especially from China. Therefore, the Wa state is also dependent on China's support politically, militarily and economically.

The Wa state in Myanmar wants to be seen entirely as a by-product of Chinese modernization. And there is no doubt that it is indeed perceived as such in both China and Myanmar, even if it is a copycat version of China. But this mountainous region on the China-Myanmar border can show us more of the region's diverse and alternative modernity.

The West often judges China by itself. What worries the "West" most about China is that China does not copy Western concepts of liberalism, democracy, and human rights. The western modernization imitated by China in more than two hundred years of contact is also the blueprint for other societies to learn from, especially the third world.

For China's neighbor, "learning from China" also always means "getting along with China". Like other peripheral areas under Chinese influence, the modernization of the Wa State developed in parallel with and intertwined with China's. Starting from the metaphor of "Shanzhai China", this article will analyze several such parallel and intertwined cases in depth.

Wa State wants to be a miniature version of China, which is actually a cheap imitation of China, but in fact the residents here have never just passively accepted China's influence. As a relatively autonomous regime, the Wa state has borrowed creatively from China. From studying Mao Zedong's military strategy in the second half of the last century to imitating China's authoritarian capitalism in the past two decades, both Mao Zedong Thought and capitalism have found their respective soils in the Wa region. Both are not only related to the corresponding social organization methods, but naturally more due to the inevitable close relationship with China. Therefore, the situation in Wa State is both a case and a comparison. That is, starting from specific cases in local history, we re-examine them under another comparative framework.

Copycats of the first kind: autonomy in the past

In fact, Shanzhai existed in many communities in southern and marginal China until the twentieth century. In places where the central government cannot reach or is weak, such stockades have a defensive function. In many areas, such villages protect residents from the intrusion of neighboring tribes or warlords, and at the same time provide shelter for rebel forces or uprising troops and strongholds to attack the surrounding countryside or plains[3].

The inhabitants of the hinterland of the Awa Mountains lived until the second half of the twentieth century in villages surrounded by fences and ditches (Fiskesjö 2001). Several tribes live in the same stockade, and sometimes several villages are surrounded to form a large stockade. These stockades provided protection during frequent armed conflicts with neighboring stockades, as well as a rear of retreat. When the Kuomintang and Communist armies came to this area in the 1940s and 1950s, these villages gradually lost their war function.

Until then the Wa people were a "stateless" society. American political scientist Scott (2009) described these societies in the mountainous regions of South Asia as "escape groups" who retreated to the highlands to escape state power in the valleys. And actually what is surprising is the opposition of Zhaizi and Bazi (valley and plain) in this area: the state or kingship confines itself to the valley area, where farmers irrigate the rice fields, the world religions and their sacred scriptures spread widely, A stable transport network allows bureaucracy and taxation to function. On the contrary, in mountainous areas, ethnic minorities live in migrating tribes, cultivate slash-and-burn farming, believe in animistic religions, and maintain relative autonomy and equality.

The relationship between mountains and valleys has thus become a central topic in the anthropological and historical studies of this Southeast Asian society, from the highlands of Assam to Laos and Vietnam.

But even though the Wa are clearly typical mountain dwellers, traditional Wa society cannot be called a "fleeing group." The reason is that the Wa people did not hide from the surrounding countries, they did not go into the mountains to escape the rule of the country. On the contrary, they often raided the nearby Shan State and sometimes captured slaves. Using the cottage as their base, they will also take revenge on the surrounding villages. Sweeps and reprisals are also used for headhunting - the skulls of enemy corpses are required for the yearly ritual of prayer before planting the seeds. Therefore, until around 1950, the Wa people were still a relatively autonomous society, sometimes plundering surrounding communities.

The autonomy of Wa society is also reflected in the independence of each individual.

Every man, and basically every woman, is seen as independent and autonomous. It is a spirit of equality (Ethos), founded on a code of honor and ethics. (Fiskesj? 2010: 244)

The struggle between clans and villages was for vengeance, and the ultimate goal was always to preserve individual and regional autonomy. Shanzhai is thus a unit of revenge politics, and such an organization ultimately ensures a relative political balance. [4]

Under the British colonial regime, the Wa mountainous areas have maintained their autonomy. Colonial officials did conduct several expeditions to the Wa mountains (as early as 1891), but concluded that there was no need to be hostile to the Wa. They were considered neither a threat (since they only hunted heads in their own region) nor value for colonial control (since they never exported anything but opium and horns and imported nothing but salt). (Harvey 1933:32)

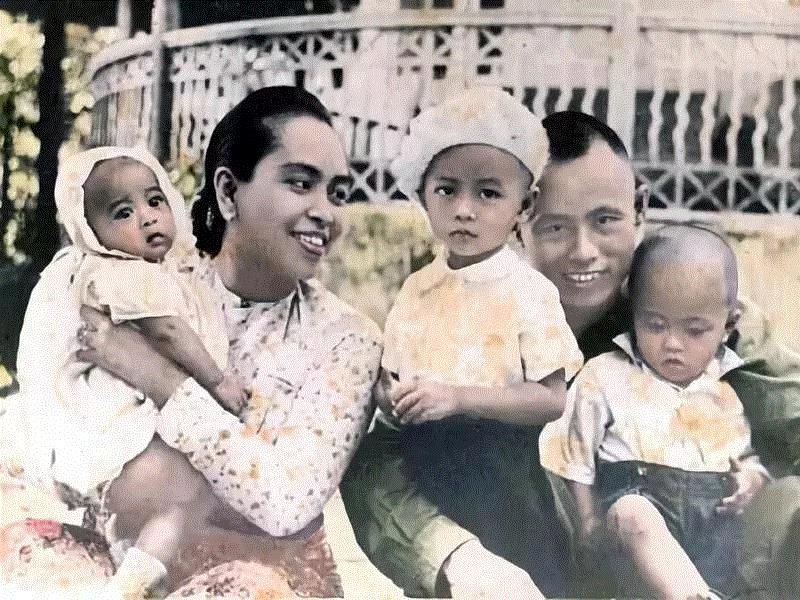

In the Second World War, the Wa people were still exempted from being involved in the war. Shortly after the end of World War II, the British colonial government started negotiations on Burmese independence with a group of young Burmese intellectuals. In February 1947, Aung San (the father of Aung San Suu Kyi) and others promised the right of self-determination to the representatives of ethnic minorities in northern Myanmar, while the Wa and several other ethnic groups were not in the negotiation.

Therefore, another mission (Frontier Areas Committee of Inquiry) was called to negotiate with representatives of these ethnic groups. Four Wa representatives attended the meeting with the committee, but apparently had little to say. Asked by the committee whether the Wa were prepared to form an alliance with other ethnic groups such as the Shan, a Wa leader said: The Wa would rather continue to live as before, independent of others.

Later Burmese Prime Minister Khin Nyunt was also on the committee. He asked a Wa representative if he would not accept schools, clothes, good food, housing and hospitals. Wa leader Hkun Sai replied:

We are very wild people, we don't care about these things.

The committee concluded that there was no need to invite the Wa to participate in the discussions because "none of them could do anything for the constitution of Burma." By the same token, the Wa mountainous areas should continue to be governed as part of Shan State.

This governance began to exist only on paper due to a lack of resources in both the newly independent Burma and Shan states. However, the Border Commission has already begun planning the infiltration of modern military forces into the Wa mountainous areas and the end of Wa autonomy. But until then Wa villages and clans lived in autonomy among themselves and with respect to neighboring ethnic groups (Shan, Lahu, Han, Burmese). The Wa want to appear reclusive in their negotiations with the committee, but they are also feared headhunters. In fact, the revenge actions among the villages and the sweeping of the valleys are the necessary conditions for the Wa people to achieve self-government.

The Second Type of Copycats: Mao Zedong Thought

The progressive modernization of the army in this region since the 1950s marked the end of the Wa's old cottages and political autonomy. As early as during the Myanmar independence negotiations, Mao Zedong-style guerrillas began to appear in various parts of Myanmar up to the mountains of Shan State. The colonial and later Burmese governments confronted them by systematically training rural military organizations.

Also in the Northeast Mountains are the Chinese Kuomintang troops who were defeated and retreated here in the civil war. In China, Communist forces began to unify the borders. In 1950 and 1951, Communist forces came to the Wa Mountains, established military camps, and set out to appease the Chinese portion of the Wa Mountains. The national border in the Wa mountainous area has long been open, and the barracks of the Communist and Kuomintang troops often face each other within visible distance. China and Myanmar completed the demarcation of the border in 1960, and this border has been maintained to this day. Much of today's Wa State was occupied by Chinese Communist forces until 1960, and Wa leaders had frequent contact with Chinese soldiers.

Many Wa chiefs who are now on the Burmese side of the Wa Mountains still maintain ties to the Communist army. After the demarcation of the border in 1960, Chinese border guards began to train the Wa people in guerrilla tactics. Communist forces supported the local Wa in their war against rival clans, Nationalist forces, and their allies. In the later 1960s, guerrilla groups developed in many Wa areas, most of which were supported by the Chinese Communist Party.

A few settlements on the fringes of the Wa mountains also received support from the Burmese army, which eventually infiltrated the Wa mountains. The Burmese Army, led by military dictator General Ne Win in 1968 and 1969, drove Communist Party guerrillas into the mountains. The Communist Party of Burma soon forged alliances with local groups, especially the Wa guerrillas. The alliance was supported and supervised by China, which at this time had begun to directly support the Communist Party of Burma.

In the next two years, the Wa guerrillas became an important part of the armed forces of the Burmese Communist Party, fighting against the Burmese army and the remnants of the Chinese Kuomintang. At the bottom of the army, they often clashed with the Burmese elite at the top of the Communist Party of Burma. Mao's methods were highly effective in organizing the Wa people and bridging the divide between Wa soldiers and the Bamar elite.

In some ways this opposition between the revolutionary elite and the soldiers below was the central issue of the Maoist revolution from which the core of Mao's thinking on war and organization developed. For example, the "mass line" means that every party cadre must stand on the "line" of the masses, and only from there can the revolution continue through constant interaction with the masses.

The Chinese Communist Party itself learned during the Long March and Yan'an that it is practical to avoid conflicts with local forces and "old forces" (secret societies, clan organizations, warlords, etc.). This pragmatism played a decisive role in Mao's mass movement and cannot be seen as a betrayal of revolutionary ideals. [6] In addition to abstract political propaganda, Mao Zedong's ideas were realized in military organization and warfare. Therefore, the war guided by Mao Zedong Thought played a vital role in the formation of the modern state of the Wa mountainous area.

In the Wa mountainous area, 1989 was also a year that crossed eras. A few months before the Iron Curtain fell in Europe, Wa military officers launched an uprising against the Burmese Communist-led leadership, and a new independent armed forces and government were installed shortly thereafter. The basis for this coup was already evident in the eighties.

After Mao Zedong's death, high-level Chinese support for Maoist guerrillas abroad cooled rapidly. Under Deng Xiaoping's leadership, relations between China and the Burmese military government began to improve, and the Communist Party of Burma has thus far been left to fend for itself. At the same time, the conflict between the Myanmar Communist Party's Burmese elite and the lower Wa soldiers intensified. While the Burmese officers were giving orders at the headquarters, the Wa mission was fighting brutally with the Burmese army. Wa soldiers have been building resentment against the Bamar leadership in the party and their arrogant attitude towards the masses.

One point of contention has been local poppy cultivation. Many ministries of the Burmese Communist Party have long relied on opium production to provide economic income. After China's aid was cut off, taxes collected from drug trade and drug production became the main source of income for the Burmese army. Bamar leaders have also tried hard-line measures to regulate the drug trade, but these measures have exacerbated their conflicts with non-Bamar lower-level soldiers.

In March 1989, Peng Jiasheng led the Han troops in the Communist Party of Burma to revolt in the neighboring Kokang area. The Wa troops led by the Communist Party of Burma were then dispatched to suppress it. Wa troops disobeyed and instead occupied the CPB headquarters in Bangsang. They burned all the documents and intelligence in the headquarters, and expelled those Bamar leaders from the Myanmar-China border. On the same day they changed their name to the "United Wa State Army", and Bao Youxiang was elected as the commander of this force and the general secretary of the "United Wa State Party".

Initially Wa junta leaders were concerned about a possible Chinese response to their coup, while China took over the former Communist Party cadres they expelled — most of whom now live peacefully in China. Relations between the Wa and China were quickly normalized based on the past connections of Wa officials (many of whom were fluent in Chinese) with China.

The third copycat: authoritarian capitalism

The Wa Army banned poppy cultivation in the late 1990s. An important reason for this change in attitude was the relationship with China, where drug production was considered a serious threat to border security. On the other hand, after the end of the "socialist fraternity", the Wa State still relies on economic and military cooperation, and drug control is for the Wa State's reputation in the process of striving for recognition and legitimacy, mainly China's recognition.

Bao Youxiang, the commander of the Wa Army, publicly stated that opium cultivation in the Wa State would be completely stopped before 2005 with the guarantee of human heads. (The head guarantee is also alluding to the past headhunting customs of the Wa people.) In fact, the Wa army's campaign against poppies was also quite successful. The Wa army has taken a series of measures, including forcing farmers to give up collecting poppy seeds, and the poppy in the fields is often completely cut off.

For farmers, the end of poppy cultivation has brought much pain. While the Wa Army helped with alternative plantations—including rubber, tobacco, and tea—many farmers lost their main source of income for a while. Because rubber, tobacco and tea take at least a year to harvest. Alternative cropping is often planned on a large scale, whereby local farmers lose their land. Either the land was given to the military who developed these plans, or the title was sold to investors.

At the same time, the military has granted more mining rights to (mainly Chinese) investors. Many small mountain mines began mining coal, bauxite and tin. Including a huge tin mine, there are also several large mines controlled by the Wa army. Most of the ore is shipped to China. According to recent reports, the tin production in Wa State has increased rapidly within a few years, which has affected the price of tin in the whole region. (Martov 2016)

In recent years, Chinese businessmen have opened more and more hotels, casinos, dance halls and shops in the few small towns in Wa State. Local hawkers and shops sell the same "Made in China" goods as stores in Yunnan. The largest casino in Wa State is located in the center of its capital, Bangsang, with 500 employees. It has multiple game halls and karaoke halls, where you can play poker, mahjong, blackjack, slot machines, etc., and two restaurants. Some Wa people, mainly relatives of Wa state leaders, also participate in these companies, or run their own hotels and restaurants.

The largest investment to date came from a Chinese investment group in 2015. In the summer of 2015, the group signed a multi-faceted agreement with the Wa State government, the core of which is to establish a "special economic zone" in Yancheng (located in Mengmao County, Wa State, main note) on the China-Myanmar border. Under difficult conditions, in July 2015 the construction of a small town with a residential area, a hospital and a square began.

Because there is not enough flat land here, many entire hills have to be leveled. For several months, various construction companies brought countless machines and workers. In September 2015, there were frequent traffic jams at the border between Wa State and China. Hundreds of trucks and tractors had to wait at the border for several days before entering Wa State.

These construction sites also employ hundreds of local workers, often recruited by Wa officials directly in their villages. Many Wa workers are not used to the strict regulations and work schedules of Chinese companies, nor do they understand the instructions given to them by the Chinese foreman. Therefore, conflicts occurred from time to time, and the Wa State Army had to mediate in them. As a guest of the local dignitaries, I had to refrain from investigating the matter directly, but I heard that in the summer of 2015 large-scale clashes broke out on the construction site, and local workers fought in groups before walking back to their villages.

This group is a good representative of the story of "big ups and downs" in China today: behind this group is the president of the company "eZuBao"; "eZuBao" became China's largest network in just one year (2014-2015) "Peer-to-peer" (P2P) credit trading market. It provides a transaction platform for individual borrowers and lenders, charging only low transfer fees. The company's single-day online turnover reached 5 billion yuan in May 2015. Basically, the company just provides an online platform for borrowers and lenders to trade directly without going through a bank. However, most of the company's transactions were found to have not been executed in December 2015. Soon the company president and a series of directors and managers were arrested. This has caused countless Chinese small and medium investors who invested in "ezubao" to lose their money (Wu Hongyuran 2015). Construction projects in Wa stopped immediately, and mechanics, foremen and managers quickly disappeared. [7] The TV station in Bangsang and the "special economic zone" in Yancheng can only commemorate the short stay of that huge investment with unfinished buildings.

Such cash crop plantations, small investments in trade and infrastructure, and planned special economic zones represent various forms of China's capital economy. For the development of local authoritarian capitalism in the Wa State, China is still the benchmark - of course, a huge neighbor has an important influence in itself. It's hard to prove, but I think the social impact of an authoritarian capitalist economy here should be similar to that in China.

In other words, relative social inequality has risen sharply, but most people's living standards have also improved compared to the past. The upper echelons of society in the government and military are like employers of Chinese businessmen, providing them with convenience. The hierarchy of the Wa State is established above that of the military, and the administrative system has only slowly begun to take shape in the last ten or twenty years. Economic investment and sound from China may not necessarily help the development of the civilian government, but may increase the centralization of the military government.

The fourth kind of cottage: the "authenticity" of the modern state

“We are China’s Africa,” a Wa official told me in the summer of 2015. In fact, the Wa state is similar to China's "new colonies" in many ways. As in the case of the colonies: the system of the colonial center was not fully adopted in the colonies. The basic characteristics of the Maoist state and current authoritarian capitalism are also evident in this region, but they are not completely copied from China, but imprinted with local colors. The Wa should not be viewed as a "failed" state without sovereignty and state institutions.

What is clear so far is that Wa residents have been pragmatic. In an environment rife with war and violence, some have figured out how to make a difference, whether it be their position between China and Myanmar, their policies on local poppy cultivation, or their business with Chinese businessmen. Classes and huge inequalities have developed in local society, but it's not just the party elite who have learned to be pragmatic. At the same time, due to the new national identity they face together, any opposition in the local society becomes moderate and acceptable.

Many young Wa people have participated in the construction of this Wa identity. "Wa Culture" and "Wa Tradition" have become important issues for Wa bureaucrats, cultural people, and even young people. Wa songs are widely popular on the Internet and social networks, and discussions are held in Wa.

One of the core topics is "what is the Wa nationality". The topic also has ideological importance, as it can justify the Wa's (relative) sovereignty. The Wa army is also actively involved in cultural work: there are propaganda teams in every area of Wa State, and several local TV stations (broadcasting in Wa, Dai, Chinese, and Burmese languages) have been set up in Wa State. built a website. There are countless videos of handsome Wa soldiers and handsome Wa girls online. These things that represent "the country and the people" provide the basis for the sovereignty and legitimacy of the Wa state, and the Wa state is considered to be the official representative of the Wa ethnic group. The impossibility of the Wa people to establish an independent state and the fragility of the Wa state regime make this anxiety about sovereignty and legitimacy even more urgent.

Such an effort is in many respects very similar to other thoroughly elusive nationalist movements. The historian Duara has described the nationalism of "Manchukuo" from a very novel angle. In some respects, the puppet regime that Japan installed in northeast China in the 1930s was deemed a failure by the Manchu aristocracy. Yet Duara emphasized that these "nationalisms" that were so impossible to achieve still reflected several universal core principles of modern nationalism (Duara 2004). Duara first emphasized the relationship between "nationality"[8] and sovereignty: the more in places where there is no hope of obtaining national sovereignty, this kind of "true" representation of "the country and the people" is the basis for the legitimacy of modern rule. demands become more urgent.

This is especially true of the Wa state today: Wa has no hope of international recognition, and its status in the Union of Myanmar is in doubt. In addition, it is relatively dependent on China. And many people are indeed discussing what is "authentic Wa culture".

They share videos of Wa soldiers singing songs or traditional dances on social networks. At this time, "ethnicity" and sovereignty are often associated. That is to say, the “really” ordinary Wa people— that is, the abjectly impoverished Wa people in the Wa state, China, and elsewhere —are the people who actually make up the Wa state and are the core source of the Wa state’s legitimacy. This legitimation has been dismissed by some observers as cynical propaganda: Western and Chinese media have often portrayed the Wa as the personal power of a group of warlords. Such a description directly denies the above-mentioned "representatives of real Wa culture", and the term "representatives" is also supported by the dispersed Wa people living in China, Thailand, and Myanmar.

Wengding Wa Tribe in Cangyuan, Yunnan (Source: Daily Headlines)

summary

The first impression of Wa State is that it is a cheap copy of Chinese modernization. However, the meaning of the word "shanzhai" can be reinterpreted in many ways. Just like saying "shanzhai products" on the Internet in China today, saying that Wa State is "shanzhai China" also has imitation contradictory meanings.

On the one hand, it's uncomfortable to say it's just an inferior knockoff. But on the other hand, sometimes this inferior position can also be exploited - at least this situation must be faced. In this context, China's copycat culture has a tinge of self-deprecation, while the Wa State, which is in a similarly inferior position, has been imitating China creatively since the 1950s, when its autonomy ended.

Before the 1950s, the Wa people did live in cottages. Under the influence of Burma and China, their strategy transitioned through military organizations and guerrillas in the 1960s and 1970s to a modern military government. A characteristic of this military state is that for decades it has relied on Chinese support and income from the opium trade.

In the last decade, poppy cultivation has been replaced by cash crops (tobacco, rubber, coffee). A large part of alternative cultivation is invested by China, as are mines, shopping malls, retail and hotels. The authoritarian capitalism of China's "party-state" is borrowed here by a military state.

While the Wa’s military-dictatorial leadership takes advantage of its geopolitical position on the China-Myanmar buffer zone as much as possible, the Wa’s system cannot be reduced to the result of war, drugs, and Chinese influence. Wa intellectuals, no matter in Wa State, China, Myanmar, or Thailand, widely disseminate the "authentic" culture and image of Wa people. On the one hand, this "authenticity" is to defend the relative sovereignty of the Wa state.

The history of imitating Mao and capitalism in China's fringes must not be viewed in isolation from their inescapable ties to China, and such imitation has always had multiple meanings—the Wa never directly embraced Maoism or capitalism. In fact, China's own situation is similar. Mao Zedong Thought itself is also regarded as a "copycat Marxism", and its capitalism and democracy in modern China also have Chinese imprints. It cannot be said that these practices in China are simply plagiarism—it cannot be said that China is accustomed to plagiarism, and "nationality" does not play any role. [9] Instead they are creative imitations, which have been going on in the political sphere. The same is true of the cottages in old China, the epitome of the empire, but sometimes they also resist the empire.

references

Chen, Yung-fa

1986 Making Revolution: The Communist Movement in Eastern and Central China, 1937-1945. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

1995 The Blooming Poppy under the Red Sun: The Yan'an Wa and the Opium Trade. In New Perspectives on the Chinese Communist Revolution. Tony Saich and Hans van deVen, eds. Pp. 263–298. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Duara, Prasenjit

2004 Sovereignty and Authenticity: Manchukuo and the East Asian Modern. Rowman & Littlefield.

Evans-Pritchard, EE

1940 The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Fiskesj?, Magnus

2001 The Question of the Farmer Fortress: On the Ethnoarcheology of Fortified Settlements in the Northern Part of Mainland Southeast Asia. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association Bulletin 21 (Melaka Papers, Volume 5): 124–131.

2010 Mining, History, and the Anti-State Wa: The Politics of Autonomy between Burma and China. Journal of Global History 5(02): 241–264.

Han, Byung-Chul

2011 Shanzhai.Dekonstruktion Auf Chinesisch. Berlin: Merve Verlag.

Harvey, GE (Godfrey Eric)

1933 1932Wa Precis: A Precis Made in the Burma Secretariat of All Traceable Records Relating to the Wa States. Rangoon: Office of the Supdt., Govt. Printing and Stationary, Burma

Kramer, Tom

2007 The United Wa State Party: Narco-Army or Ethnic Nationalist Party? Singapore; Washington, DC: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies; East-West Center Washington.

Martov, Seamus

2016 Have the Wa Cornered the Global Tin Trade_. The Irrawaddy, February 25.

Rutherford, Danieln

2008 Why Papua Wants Freedom: The Third Person in Contemporary Nationalism. Public Culture 20(2): 345–373.

Scott, James C.

2009 The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. NewHaven: Yale University Press.

ter Haar, Barend J.

1998 Ritual and Mythology of the Chinese Triads: Creating an Identity. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

Wu, Xiujie

2010 Verf?lschenals Zeichensetzen: die Shanzhai-Bewegung (in China). In Mareile Flitsch, AndreasIsler, Lena Henningsen und Wu, Xiujie (Eds.), Die Kunst des Verf?lschens:ethnologische überlegungen zum Thema Authentizit?tell; Supplement ung zur Aus “Die Kunst des F?lschens - untersucht und aufgedeckt” des Museums für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 29.1.-30.5.2010 im V?lkerkundemuseum der Universit?t Zürich, pp. 36-45. Öt Zürich.

footnotes in the original text

[1] In 2010, Mareile Flitsch and her colleagues curated the exhibition "The Art of Counterfeiting" at the Völkerkundemuseum in Zurich, which also highlighted many interesting examples of fake art, see Wu 2010.

[2] There is no reliable evidence to confirm that China has indeed provided military assistance to the Wa Army. The Wa Army also denied that China was supplying armed helicopters.

[3] There are countless cases of peasant uprisings and resistance in China, most of which are messianic movements based on cottages. For example, ten Haar (1998:236ff) studied the peasant uprising in the Dabie Mountains from 1750 to 1752.

[4] Therefore, the traditional feudal politics produces an "anarchic order", such as the description of the "fission lineage system" of the Sudanese Nuer by the British anthropologist Evans-Pritchard (1940).

[5] See Kramer (2007:9-10)

[6] In his book on the Chinese revolution, Chen Yongfa emphasized the "limited discrimination" of the Communist army and the "local mobilization" of the masses. These two concepts refer to the pragmatism in the movement: we should treat friends and enemies differently, but the distinction is limited and must be within a certain framework; we must give interests and personal relationships to mobilize the masses and organizations. Chen Yongfa explained in an article (1995) that although the Communist Party itself rejected opium, the Communist Party's economy in Yan'an was largely supported by taxes on opium cultivation. Pragmatism thus does not mean abandoning revolutionary ideals. Specifically, the Communist Party, at least within its own ranks, completely banned opium smoking. In this regard, the revolution led by Mao Zedong became a model for the Communist Party of Burma and the Wa Army.

[7] As elsewhere, the investor group owed wages to workers here. Some bloggers say she still owes 170 million yuan to Wa workers.

[8] The "nationality" mentioned here is generally translated as "authenticity", and the English is "authenticity", which is translated as "nationality" here for the convenience of understanding. ","practical thinker.

[9] This is also the central thesis of Byung-Chul Han's "Shanzhai" (2011).

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…