‘Strike Down Hard Resistance and Regulate Soft Resistance’ - The Securitisation of Civil Society in Hong Kong

(This article is first published on Made in China Journal on 8 March 2022)

It is difficult to capture a flying bullet on camera. And when the perpetrators of violence are firing numerous bullets with unpredictable trajectories, the cameraman may well end up a victim. This metaphor, unfortunately, aptly describes efforts to document the current crackdown on civil society in Hong Kong.

In May 2021, the Made in China Journal first invited me to contribute an essay. Back then, almost all opposition political figures in Hong Kong were already in custody for National Security Law (NSL) violations, but Apple Daily, the city’s largest prodemocracy newspaper, was intact, and many trade unions and many nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) were still operating. However, two months later, Apple Daily, the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union, as well as dozens of civil society groups founded after the 2014 Umbrella Movement were gone. My initial plan for the essay was to capture responses from civil society organisations (CSOs) to the strict and repressive regulatory regime. This subject became less and less relevant because the rights-based CSOs on my radar started to crumble, disband, and cease operation. Amnesty International Hong Kong, a human rights organisation with which I am deeply involved, announced the closure of its Hong Kong office in late October 2021, stating that ‘the national security law makes it impossible to know what activities might lead to criminal sanctions’. Stand News, a non-profit multimedia outlet in Hong Kong, documented that 58 groups had disbanded or ceased operating in 2021. On 29 December 2021, Stand News became the fifty-ninth group to shut down after police raided its newsroom and arrested its senior executives.

This shrinking of civil space in Hong Kong is unprecedented, and the conditions that CSOs must consider—such as changing regulatory frameworks, increasing political and legal risks, and new internal dynamics within the organisations—are highly volatile. Criminal liability under the NSL and penal code are not the only things CSOs worry about. There is also the backdrop of state securitisation of civil society. Chinese Liaison Office Director Luo Huining first introduced the concept of ‘soft resistance’ (软对抗) on National Security Education Day in April 2021, using the term to indicate indirect resistance via media publication, education, and cultural activities. On that occasion, Luo vowed that ‘hard resistance should be stricken down by law, soft resistance should be regulated by law’.

Subject as they are to increasingly strict regulation and surveillance by various government departments, ranging from tax and civil affairs to health and hygiene, CSOs are under constant threat of being ‘stricken down’. This essay will highlight how both criminal liabilities and the subtle securitisation of NGO regulations pose new barriers to the activities of CSOs, occasionally leading to self-censorship. This leads us to discussion of a topic about which no-one has a clear answer: the future. How will Hong Kong CSOs evolve to continue their work and achieve the changes for which they are striving?

Criminal Liability and Endless Risk Assessment

The largest deterrence to CSOs’ work remains the potential for criminal liability under a vague, ill-defined national security regime. Despite repeated official reassurances that the NSL adheres to international human rights provisions, few believe this to be true when it comes to the protection of freedom of speech and expression.

The four core criminal provisions in the NSL—secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign entities—are written in vague and overly broad language and can easily be used arbitrarily on political opponents of the regime. Officials have been giving obscure responses when they are asked what types of activities or behaviours would breach the law. For example, a few days before the latest annual commemoration of the Tiananmen Massacre of 4 June, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam refused to clarify whether the five operational goals of the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China (which include ‘ending the one-party dictatorship’) would constitute subversion. A few months later, organisers of the alliance were apprehended and charged with inciting subversion of state power. Likewise, three weeks before Stand News was raided and forced to shut, Hong Kong Security Chief Chris Tang vowed: ‘The authorities will relentlessly search for evidence to go after anyone threatening national security or violating the law in disguise of media and NGOs’—without clarifying which media and NGO activities would constitute a crime.

Amid such uncertainty, it is no surprise that ‘risk management’ has become the most important task for CSOs. In a nutshell, their risk assessment generally begins with a mapping of compliance risk—a process through which they identify high-risk areas of work and action. Next, CSOs must consider the likelihood of noncompliance and legal enforcement, and the severity of impact in the event of enforcement. Finally, CSOs need a mitigation plan, such as altering the corporate structure of the organisation, amending program output, and implementing internal due diligence and control measures. These steps have become very time-consuming and complicated because of the arbitrariness of the NSL regime. In my experience, before the NSL, the assessment of compliance risk was a one-off task in the planning phase of each one-to-three–year project cycle. Living in a society based on the rule of law meant people could easily assess the legality and possible consequences of their actions. The one-off risk assessment was often valid and reliable for the life of the project, but this is not the case under the NSL regime.

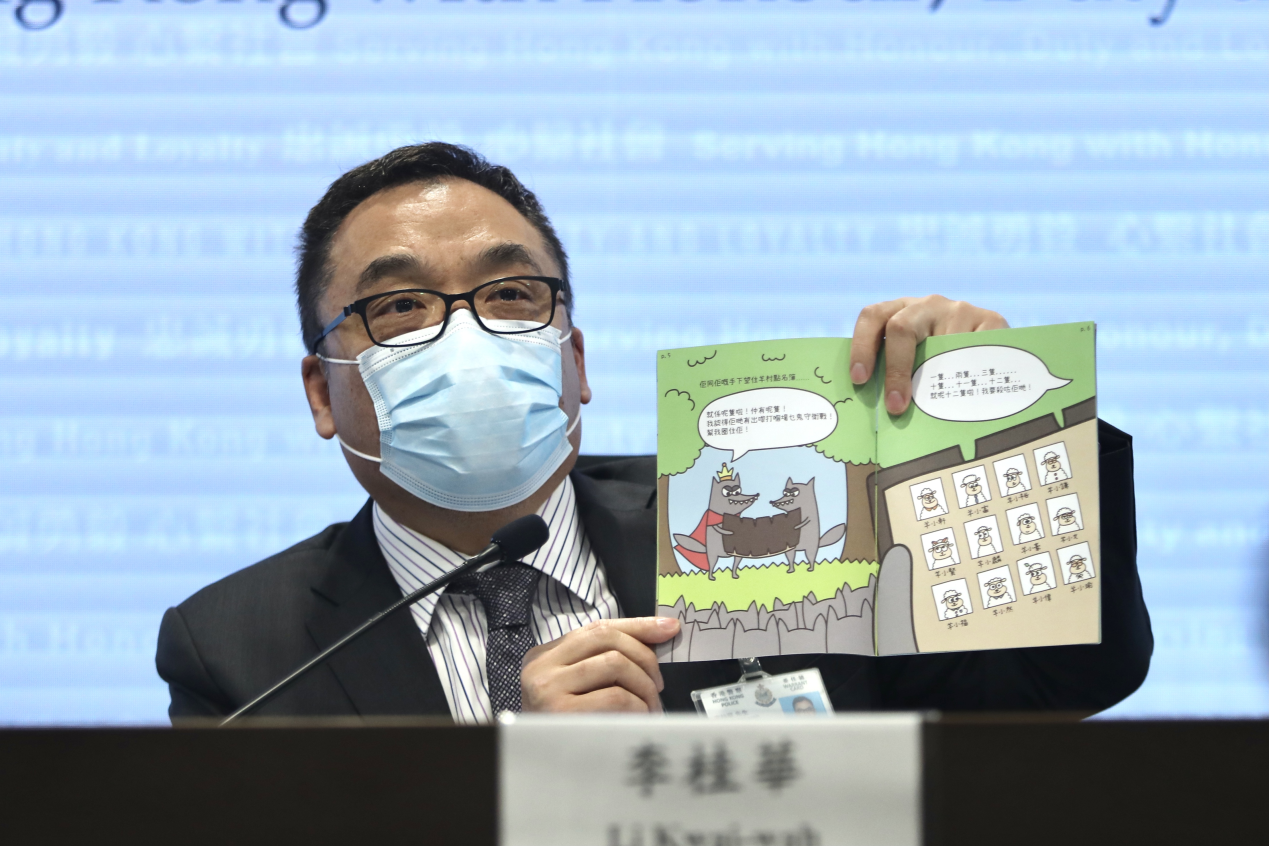

Selective legal enforcement is now frequent, and people must continuously speculate whether they are on the authorities’ hitlist. Politics has therefore become paramount in these assessments. Before the enactment of the NSL in July 2020, no-one would have expected participation in a primary election would constitute subversion of state power. Before November 2021, it was unimaginable that judges would indict someone who simply chanted protest slogans in public for inciting secession and sentence him to almost six years in prison. Before July 2021, no-one expected the authorities would revive a sedition law enacted by the British colonial government in the 1930s to use against a prodemocracy unionist who published children’s books.

‘In the past, we did risk assessment; now we do political assessment’, I was told by Ivy, an activist working for a local environmental NGO who agreed to share their organisation’s internal risk management process on condition of anonymity. ‘We used to know clearly the potential legal consequences of our actions. For instance, what maximum penalties we would receive for holding a banner. Now, risk assessment has become political assessment.’ How to locate the red line has become a popular topic among CSOs. The cold fact, however, is that there is no red line, but rather a ‘red web, red carpet, and red sea’—a metaphor used by Daisy Li, the founder of Hong Kong Citizen News, an independent news website that also ceased operations in early 2022 to avoid a likely crackdown.

One of the indicators used by CSOs in their political assessment is whether they are being targeted by pro-government media. For some CSO executives, one of their morning tasks is to check ‘Support.hkmedia.propaganda’, a volunteer-run Facebook page that aggregates the stories of the day from pro-government mouthpieces. Some will differentiate between the sources of information to assess the level of threat their organisation faces. For instance, they will consider whether the rhetoric is coming from a pro-government mouthpiece or from someone in the pro-establishment camp, whether the criticism is coming from mainland China’s propaganda machine—for instance, the Global Times—or from local news outlets. All this guesswork takes time, and time is one of the scarcest resources in CSOs as most donors and funders do not regard risk assessment and mitigation as part of their funding mandate, and CSO staff are already under pressure to meet the key performance indicators of their program.

Restraints on Funding

Even CSOs that have abundant funding are not free from worry, as all fundraising methods have been greatly disrupted by the new regulatory regime. A core criminal provision in the NSL concerns ‘collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security’, and we learnt from evidence tabled by prosecutors in court that even being followed by foreign politicians on Twitter is considered an act of collusion. Such an overly broad interpretation of the law has a chilling effect on both international and local NGOs in Hong Kong.

While Hong Kong was once a favourable location for many international NGOs (INGOs) for their regional hub, its attractiveness is rapidly diminishing. In 2013, there were 215 INGOs operating in Hong Kong. According to a 2015 survey, 18.5 per cent of the income of these INGOs came from overseas foundations and 16 per cent from overseas governments. UN experts have emphasised that CSOs have rights to seek funding without restriction, both domestically and internationally. The Chinese Government, however, has a long history of blaming foreign governments for sponsoring ‘colour revolutions’ and of accusing NGOs that receive overseas funding of being ‘foreign agents’. Using new powers under Article 43 of the NSL, the Hong Kong police have demanded that rights-based NGOs, such as the Hong Kong Alliance and the China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, provide details of their activities, financial information, and personal data. CSOs fear their overseas funding will be used as a justification for the government to acquire sensitive data about their staff, project partners, and beneficiaries. As a result, some have decided to break ties or reduce interaction with overseas donors and INGOs.

CSOs that rely on local resources have also found themselves navigating a minefield. Under national security obligations, many government branches—from the Education Bureau to the Commerce Bureau and even the Fire Department— have included national security elements in their policies. The Tax Bureau has tightened its control over the 9,400 charities in Hong Kong. Charitable organisations that take part in activities ‘contrary to the interests of national security’ will no longer be recognised as a charity and will no longer enjoy tax exemptions (IRD 2021). The Tax Bureau has been making inquiries among charitable organisations, requesting detailed information about their past advocacy and campaign activities. Some CSO executives worry that past acts of defiance—such as joining calls for social and political reform or joint campaigns with prodemocracy lawmakers—will be used against them. If the bureau determines that any of their activities fall outside charitable purposes, the organisation will need to pay compensation. Even worse, their tax-exempt status could be revoked. For many, tax-exempt status is the ticket to access funding from local charitable foundations and companies; losing it would severely undermine their financial sustainability.

Hong Kong has a robust set of regulations on public fundraising activities; the Social Welfare Department, Home Affairs Department, and even the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department all take part in licensing and scrutinising activities like flag days (that is, days of public fundraising for charity), charity sales, and the solicitation of donations in public. Without proper checks and balances, as well as complaint and accountability mechanisms, these fundraising regulations could be weaponised to pressure CSOs. For instance, a new permit mechanism for face-to-face solicitation of donations in public was enacted at the beginning of 2022. Under this new rule, only charitable organisations with a credible track record are eligible to conduct face-to-face solicitation. In addition, their permits are subject to review every six months, and quotas mean organisations must compete for permits.

The new regulations are a sword of Damocles suspended over the heads of Hong Kong CSOs; to survive, they must discipline themselves, self-censor, stop certain kinds of work, and/or restructure. To err on the side of caution, some CSOs have indeed begun to self-censor and impose robust gate-keeping systems on their public statements and comments on social media. These strategies include staying under the radar by reducing their media exposure, avoiding naming and shaming government officials, removing or altering old social media posts, or even deleting their social media pages entirely.

Many in the sector anticipate the rules on charities and non-profit organisations will tighten even further in the future. In 2011, the Hong Kong Government proposed the enactment of a charity law and, in a consultation paper published the same year, the Charities Sub-Committee of Hong Kong’s Law Reform Commission recommended excluding ‘human rights, conflict resolution or reconciliation’ from the definition of charitable purposes. The proposal was shelved, but in 2021, some pro-Beijing lawmakers began calling again for a charity law. One can only assume if such a law is introduced, rights-based groups or those that focus on legal reform and advocacy will be further marginalised.

Exodus of CSO Personnel and Mental Health Impacts

People who work for CSOs are in a precarious position. They are enduring intense psychological pressure, which has led not only to widespread feelings of resignation, but also to a wave of emigration from Hong Kong. In the previous four decades, Hong Kong’s civil society operated in a relatively vibrant, safe, and peaceful environment, so many CSO executives, including boards of directors, have a relatively low tolerance of risk. Now they face considerable stress, and there have been three waves of CSO disbandment in the past 12 months alone. Each wave occurred after a prominent prodemocracy group—respectively, Apple Daily, the Hong Kong Alliance, and the General Union of Hong Kong Speech Therapists—was forced to disband and its senior executives were arrested on sedition charges. Some CSOs decided to fold because they could not afford costly legal battles if their members were targeted; others felt they could no longer pursue their social mission under the changed conditions. On top of this, the authorities have resorted to extralegal tactics to intimidate civil society. Many labour and rights-based groups were attacked in pro-government media, and some were harassed over the phone, followed, or invited to ‘drink tea’ by law enforcers—a practice eerily reminiscent of strategies long used by state security on the mainland.

More than a dozen CSOs on my radar working on issues spanning poverty alleviation, the environment, labour, and human rights have lost staff and senior executives in the past six months. This internal reshuffling and brain drain have intensified the administrative burden, and negatively impacted the mental health of remaining staff. It is common for CSO workers—including me—to experience insomnia, anxiety, fatigue, disorientation, a sense of guilt, and loss of meaning in their work. Putting it into a larger context, the overall mental health of all Hong Kong people has deteriorated as a direct result of social unrest combined with the Covid-19 pandemic. Researchers have observed that an alarming 19 per cent of Hongkongers suffer from depression, and 14 per cent from anxiety. Every CSO employee I know has someone they know who is in detention for social movement–related offences; many are traumatised by the separation.

Thankfully, mental health and wellbeing are not taboo topics in CSOs’ cultures. There are grassroots initiatives that promote trauma transformation and mental wellness. Practices of wellbeing and nonviolent communication in the workplace have become increasingly popular in CSOs. Although local prisoner support networks like the 612 Humanitarian Fund and Wallfare shut in late 2021, there is a culture of mutual-aid networks to support detainees and their families.

What Next?

In liberal democracies, CSOs often influence policymaking through research and lobbying, and by mobilising public pressure. Although Hong Kong was never a full democracy, CSOs were largely operating in a liberal paradigm. With the rules of the game having changed so dramatically, CSOs will have to adapt their strategies. Ivy explained that in the past,

step one [of our work] was research, step two was media publication, step three was advocacy and lobbying … today it has become very challenging to take steps two and three. Government ignores [advocacy] from CSOs because they are less concerned about their legitimacy … as the media space is narrowed, dissemination [of our messages] has become less effective in reaching broad audiences.

Moreover, the mass disqualification and arrest of almost all opposition political figures have weakened the advocacy abilities of CSOs. Pan-democracy lawmakers and CSOs enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship in the past, with the former facilitating the latter’s access to government data and information and the latter contributing research and policy suggestions for the lawmakers. This equilibrium was broken when Beijing unliterally changed the electoral system of the Legislative Council, effectively barring any opposition from gaining a seat on the council.

Under these changes, CSOs must revise their strategies. To gain access to, recognition, and resources from the government, some organisations might focus on providing services and refrain from any organising and empowerment work—a shift we have also observed in mainland China over the past few years. To further marginalise rights-based, organising, and advocacy-oriented CSOs, the government is likely to impose greater oversight on private foundations and donors, cutting off funding to CSOs with a progressive agenda. This will also pose some challenges to the authorities, as the exclusion of such an important segment of civil society will see the government lose a source of information about citizens’ grievances.

It is evident that Hong Kong authorities will further securitise civil society by undermining its leverage, placing it under heavy surveillance, and curtailing the autonomous space in which citizens can connect and build power. We should not view this as the end of Hong Kong civil society, although we should acknowledge the contentiousness of this process of securitisation. Many activists who were affected by the disbandment of CSOs are experimenting with innovative ways to cultivate civic virtue and promote democratic values. The decentralised, fluid mass movement of the past few years has provided citizens with the experience and a toolkit to self-organise without institutional support. Although Hong Kong lost many CSOs in 2021, new citizen initiatives ranging from community-building to book clubs and cultural activities are blooming. Of course, the authorities will come after these spaces, too. However, as a friend said, once we taste freedom, we will never resign ourselves to being caged.

Featured Image: Pressure Gauge. PC: Shane Horan (CC).

喜欢我的作品吗?别忘了给予支持与赞赏,让我知道在创作的路上有你陪伴,一起延续这份热忱!

- 来自作者

- 相关推荐