Happy Birthday|Professor Reyila Dawuti, a Uyghur scholar

A few days late, this past Thursday (5/20), it was the birthday of Uyghur anthropologist Professor Rahile Dawut (راھىلە داۋۇت, Rahile Dawut), on December 12, 2017, I received a call asking her After the phone call to Beijing, she hurriedly went out to Urumqi Diwopu Airport. Since then, relatives and friends have lost contact with her, and there is no news of her. As the first batch of Uyghur women to receive doctorate degrees, Professor Reyila Dawuti worked at Xinjiang University. His work for many years has been recognized by the Chinese academic system. He has been a member of the Communist Party of China for more than 30 years. He is careful not to involve any political issues. , she is still not immune to the calamity that befell her compatriots.

On this special day, Reira's daughter Akida Pulat made a short video for her mother to express her thoughts and retweeted an article published by the magazine "ELLE" on the same day. Feature article .

And what I still remember is that on this day last year, Akda wrote a letter to her mother who had been missing for several years . One of the paragraphs read:

Many people comfort me by saying 'Your mother is a strong woman. She can endure the hardships'. But I can't comfort myself. You are human. Humans need freedom, the warmth of the family and friends, and home. No matter how strong you are, day after day, the loss of freedom and hope will make you weak…I need to take the risk. I need to see you coming out of that place as soon as possible.

That night, I was on the night bus returning home. I was wearing a mask. The environment in the back half of the bus was shaking and claustrophobic. With the dim light of my mobile phone, this text was very touching and emotional. It reminded me of my academic career. In the book, I read a discussion about Professor Jeira Dawuti.

Khätmä

Rachel Harris, an anthropologist at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, has been a long-time friend of Professor Reyla. In a journal article, she profiled the conversation between Duan and Reyla, about how researchers should What posture should the discussion take (should it be contextualized and fully empathetic to people's emotions? Or should I maintain a certain emotional distance, keep calm and focus on recording?).

Their discussion focused on Khätmä, a female ritual practiced in the Uyghur countryside.

Khätmä can be succinctly interpreted as a collective ritual where women gather to recite the entire Koran one after the other during Ramadan, and the whole Koran is divided into 30 parts for Khätmä, one segment each night; however, such occasions, like other similar Uyghur traditional practices, The process of Khätmä is very Central Asian Sufi: the chanting process will be interspersed with various Sufi overlapping prayers (dhikr). Fall into a trance, or sob in a low voice, or cry aloud. The participants believed that this was a concrete manifestation of their longing for God Himself—bringing the oppression and pain of the world to God, gradually losing self because of their focus on Him, and at the same time feeling deeply trapped in the world. Suffering, separated from God's love and mourning.

In the rural areas of southern Xinjiang, Uyghur women often have no open, institutional way to learn and practice Islam due to gender segregation and state repression. As a result, they would meet regularly in the living room of certain households in the village to learn all about the Islamic faith, usually led by the female ceremonial elder (Büwi) of the village. And Khätmä was part of this hours-long gathering.

Harris recounts his first Khätmä involvement: one summer day, more than 50 women huddled together on a large kang in the same living room for more than three hours of partying. "I was almost completely unprepared for the baptism of such an extremely hot environment and a wave of strong emotional shocks." She described the shock she suffered. Interestingly, after the meeting, the Uyghur women who attended the meeting repeatedly asked the British scholar curiously: "Did you sob along?"

But in fact, Harris was still in the mood of "I participated in an important ritual with profound anthropological significance! I must grasp it! But am I in the best state now? Is there something missing?" A complex mental state, both excited and anxious. She thought that this was the most important ritual moment, and she did not make the corresponding and careful psychological preparations, so she was "unworthy" to cry with the women, so she endured the high emotional tension in the crowded and stuffy space. Stop the tears and do the duties of an anthropologist: try "while holding the camera firmly, trying to sort out and record the rhythm of the Khätmä and the repeated chants in the complex vocals".

Afterwards, Harris shared the incident with Reira, and also took the opportunity to ask Reira, who is experienced in the field, how to deal with it. Reira said with a smile that the Khätmä scenes she participated in are very similar, hot, crowded and full of emotions, but her method is very different from the former. She adjusts her mentality comfortably, allowing herself to fully feel the people on the scene and follow the flow emotions, let yourself cry. Seeing Reira who was crying along with her during the meeting, the women in the meeting were very happy and proudly pointed at her after the meeting and said, "Look, she is a true Muslim!"

"The hot oil in the pot is sizzling! You have no choice." The leading female Sufi described the emotional emptiness and the spiritual emptiness of people's longing for God - if people suffer intensely during the ceremony It's just as unreasonable not to put meat and vegetables into cooking in the face of a sizzling oil pan. Compared with Reira's soft figure, Harris remorsefully commented on himself afterwards: "I should have let the tears dominate everything."

It is really a dialogue that is hard not to be reminiscent of Geertz's "cockfighting moment" (those who have been exposed to anthropology will know what I'm talking about), and also echoes Professor Reyla Dawuti's ten years in southern Xinjiang. The familiar attitude of several years of fieldwork: respect and respect for local grass-roots figures, hospitality and generosity to foreign scholars, and always friendly and easy-going .

Mazar

In fact, both scholars have made outstanding contributions to contemporary Uyghur research: Harris specializes in ethnomusicology, Islamic practice, and soundscape construction, and is one of the few who have had the opportunity to study ethnic groups in rural southern Xinjiang. Western Scholars of Music and Female Sufis.

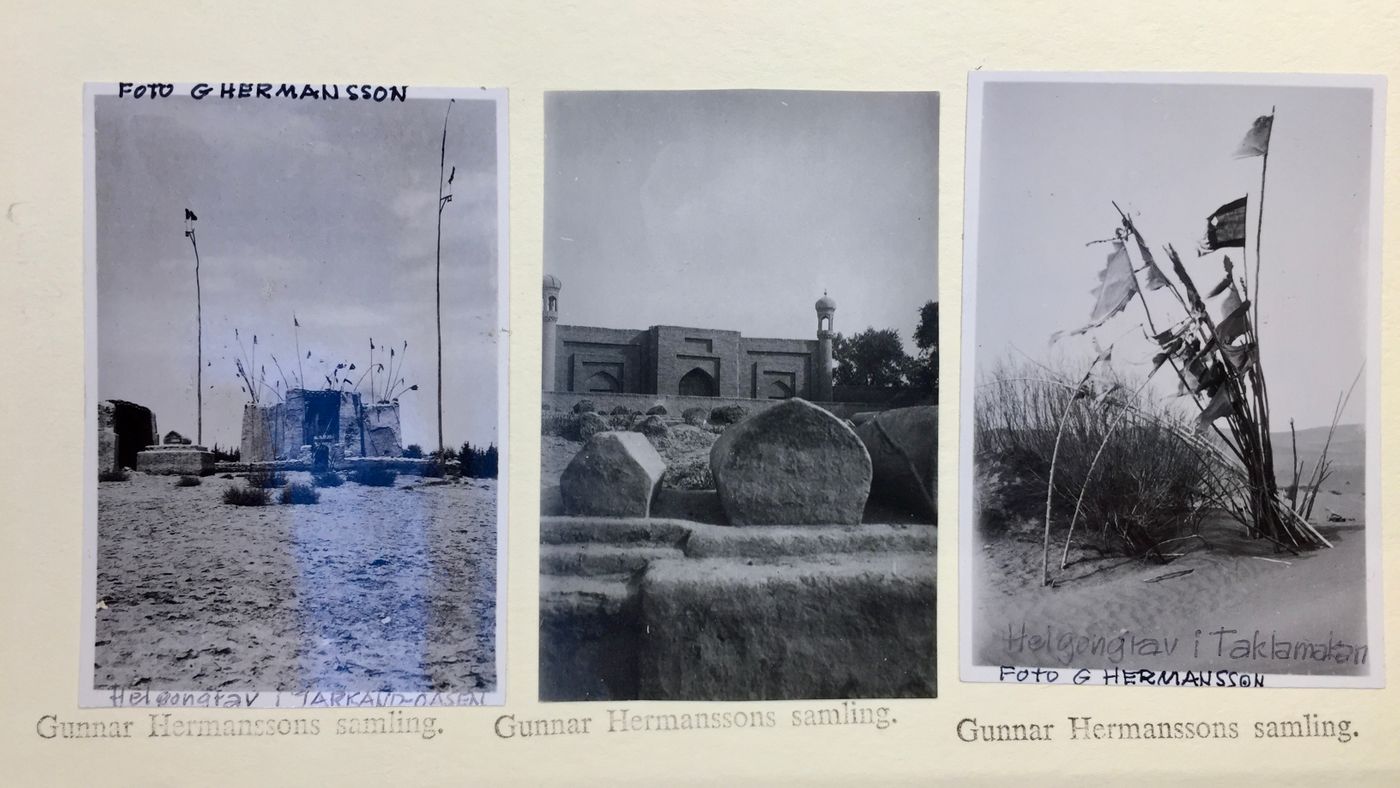

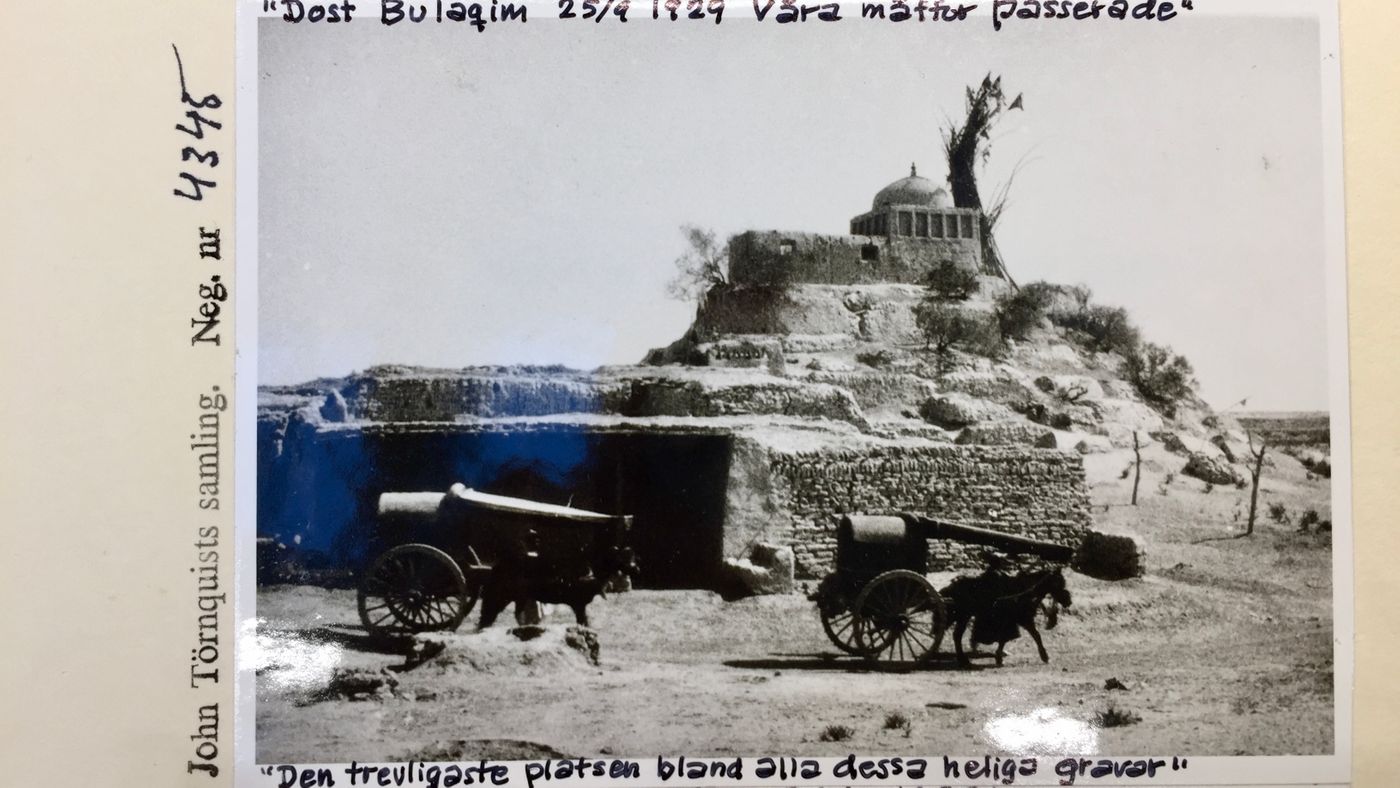

Professor Reyila Dawuti has devoted himself to the study of Uyghur Mazar culture since he obtained his doctorate degree from Beijing Normal University (Mazar is the Chinese transliteration of Uyghur "grave" مازار, the etymology comes from Arabic) .

For hundreds of years, Mazha has not only been a tomb for the residents of the Tarim Basin, but also a special space with a distinct social and religious nature: people will go into the desert in pairs at certain times, and walk to the heights of colorful cloth and towering buildings. The Islamic saint of the branches, Maza, holds small sacrifices with livestock as offerings, and activities with local colors such as vigils and prayers. In addition, as a specific space where the local society is intertwined, reorganized, and re-embedded, the cemetery is also an extremely important social field for Uyghur villages. Cooking and sharing food, taking a sand bath, meeting the opposite sex, even gambling, cockfighting.

Before the government's strong intervention, Reyila interviewed countless villagers, participated in various ceremonies, recorded various practices around the Mazha Holy Land with words and images, and tried to understand the impact of this special space on the spirituality and society of the Uyghurs. meaning. However, in the past ten years, traditional gatherings such as those held around the Holy Sepulchre, as well as various Uyghur cultural practices mentioned above, have been banned by the government.

The edge of the desert is never barren. They have their own social significance unique to Uyghur culture, marking the centuries-long practice and historical identity of the Uyghurs and the Taklimakan oasis along the coast. As a scholar, she is well aware of this. road. However, Reira's own fate seems to be closely linked to her decades-long Uighur cultural practice, and in late 2017 she disappeared into a large government-imposed detention system.

As Rian Thum, a historian of modern Uyghur history, said in an interview :

To in any way valorize elements of Uyghur culture–to valorize it simply by deeming it worthy of study–seems to have been turned into a sign of disloyalty in the eyes of the government [...] The government retroactively made activities that it had approved of before, illegal, and it punished people for those, sometimes going back over a decade.

Nameless, this has nothing to do with loyalty, and it has nothing to do with being in or out of the system. As long as it involves the uniqueness of Uyghur culture and its connection with the land, this country can arbitrarily withdraw its recognition of you and treat you with mercy. Punishment with no explanation at all.

Freedom

On the birthday of Professor Reira Dawuti, I pondered over the discussion of field experience and Akda's text, about the so-called freedom:

You are human. Humans need freedom, the warmth of the family and friends, and home. No matter how strong you are, day after day, the loss of freedom and hope will make you weak.

It seems that this cry is also in line with the situation that various Turkic groups in Xinjiang have encountered in recent years. What exactly is freedom?

I think freedom can take many forms, but mixed with the words I read about Uyghur culture, the freedom I can imagine is that one can naturally trust another person, can invite relatives and friends to be guests at home, and No need to worry about surveillance or uninvited "relatives". Freedom is that people can practice Islam the way they are used to, they can observe Ramadan, they can do Khätmä, they can gather to recite the Koran aloud. Even more so, because of the power of metaphysical belief, you can sob lowly without worrying that you will be imprisoned. Freedom is that people from cities and foreign countries can also enter the village, and they can feel the profoundness of Islamic belief and the diversity and tolerance of Uyghur culture.

Freedom may be an abstract concept, but it also comes from the presence of relatives and friends. Freedom is the continuation of daily life without interruption, and the warmth of home. Freedom makes man strong and man. Freedom is that people can openly claim to be a Muslim without suffering. Freedom is that the anthropologist can no longer be detained by the government for her Uyghur/Islamic studies. Freedom is a way for Prof. Reira Dawut to reunite with her family and to resume her research and her dreams.

Freedom is the most basic thing, freedom from fear and uninterrupted by violence.

At the end of the letter, Akda concludes with excerpts from the diary of Anne Frank, a Holocaust victim of World War II:

Where there's hope, there's life.

It fills us with fresh courage and makes us strong again.

Happy birthday, Professor Reira Dawuti, thank you for the profound inspiration your research has brought me. Although it has been many years, I sincerely hope that you will be released soon and reunite with your family smoothly.

This article is adapted from a short article shared only privately on the same day last year.

Regarding Professor Reira Dawuti's contribution to the study of Uyghur culture, the whole story of her disappearance, and the support of the international academic circle, you can refer to the earliest reported article in The New York Times, or my own writing on the outside station . For the video of the Uyghur women's ceremony mentioned in this article, please refer to the research project website Sounding Islam in China . If you want to continue to follow the follow-up situation of Professor Reila Dawut, please follow the website Free Rahile Dawut operated by Akda.

Ref.

Harris, Rachel. 2014. "The Oil is Sizzling in the Pot": Sound and Emotion in Uyghur Qur'anic Recitation. Ethnomusicology Forum , 23 (3), 331-359.

Harris, Rachel., & Dawut, Rahilä. 2002. Mazar Festivals of the Uyghurs: Music, Islam and the Chinese State. British Journal of Ethnomusicology , 11(1), 101-118.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More