Orientalism, Multiple "Edges" and Aesthetic Liberation: A Review of the Chen Man Incident and Its Controversies

1. The Chen Man Incident and Oriental Aesthetics

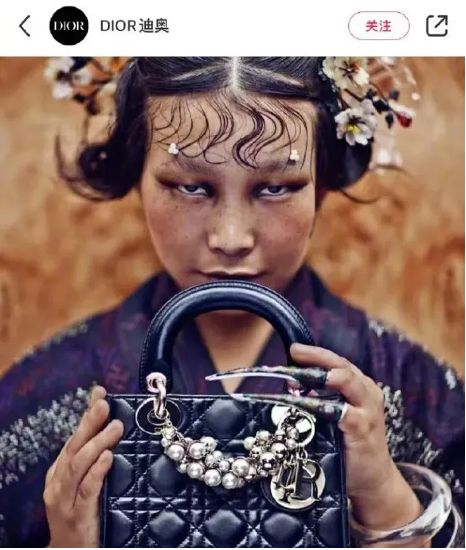

In late November, famous photographer Chen Man's series of "Arrogant Conservation" shots for the French fashion brand Dior's art exhibition in Shanghai caused controversy on social networks. The sombre look and highly stereotyped face of the female model in this set of exotic photos are considered by many netizens to be a smear of Asian/Chinese female images.

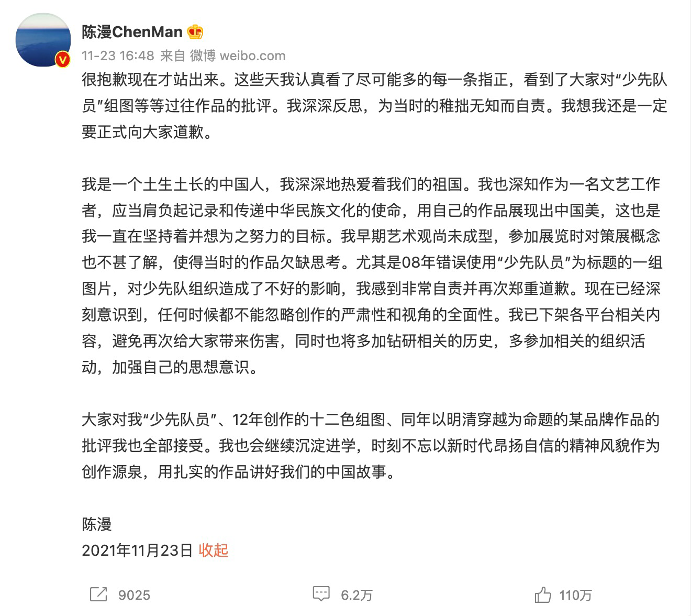

In this regard, the People's Daily Online commented: "Chen Man's creative freedom should be guaranteed, but she is accustomed to creating an artistic image that caters to Western aesthetics, which is unflattering."[1]November 23, Chen Man On his personal Weibo, he apologized for his photographic works, saying that when he created the pictures of "Young Pioneers" in his early years, "the artistic concept has not yet been formed" and "caused a bad influence on the organization of the Young Pioneers". Criticism of the two groups of photography and "Pride of Preservation" [2].

The term "catering to the West" here refers to a set of stereotypes about Asian/Chinese groups in Western society. For example, the recently released overseas Marvel movie "Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings" has been criticized in China for its actor image and its spectacle-like representation of oriental customs and society[3]. Historically, Fu Manchu, with a long slender beard, a sinister smile, and a sinister cunning, is a typical oriental image in Western popular culture.

In fact, the stereotyped treatment of Chinese women in the fashion industry is not uncommon in today's Chinese cultural ecology. For example, in June this year, the model for the graduation fashion show of the Tsinghua Academy of Fine Arts caused controversy. Fashion designers have generally used models with narrow eyes and extended eye makeup, which is considered to be an implicit pandering to the "slit-eyes" of Asians in Western prejudice.

This kind of specific imagination that has been maintained in the West for a long time, and even passed from the West to the consciousness of the East, is called Orientalism by cultural critic Edward Said. The so-called Orientalism, that is, some symbols and images identified as "Oriental", are generated and fixed based on the West's imagination of the East . This representation of the other in the East includes the power and gaze of the West towards the East, and occupies a certain dominant position through the dominant cultural system of Western society. If this stereotype is “transferred domestically” through Western culture and internalized by the East itself, it is a manifestation of “self-orientation”, that is, the East imagines and represents itself through the way the West imagines the East. The above-mentioned domestic fashion phenomenon can be understood as the result of some kind of self-orientation.

Controversy caused by a series of incidents surrounding Western stereotypes, including Chen Man's photography, is enough to show that Orientalism, a kind of Western intellectual hegemony, has become increasingly popular among Chinese people in this era of "cultural confidence". perceived and disgusted. However, as a concept of cultural criticism, Orientalism is not only substantially different from nationalist discourse, but the object it points to may also be in a more complex real power system . In the details of the Chen Man incident, we can also find multiple intertwined aspects of discourse and power. Based on the Orientalist critique of the series of photographs of Pride and Conservation, this article intends to delve into the details of this issue in order to explore and activate further thinking on power, aesthetics and otherness.

2. The Orient and Multiple Center-Edge Relationships in "The Twelve Colors of China"

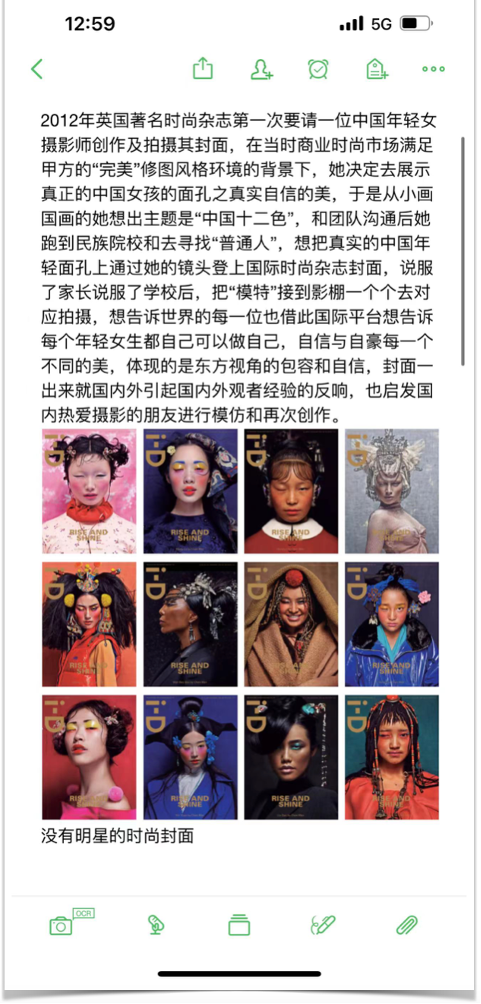

In the case of Chen Man, the criticism of her extended from the original "Pride of Conservation" for Dior to her other previous works, such as "The Twelve Colors of China" in 2012. However, if we carefully examine "China's Twelve Colors", we will find that not all the female models in it have "squinted eyes", leaving the viewer with the impression of "small eyes", which may be partly due to the fact that all the models are closed left eye. In fact, Chen Man once explained that the use of ordinary people and many ethnic minority models in the shooting was to show "real young Chinese faces" through the lens [4]:

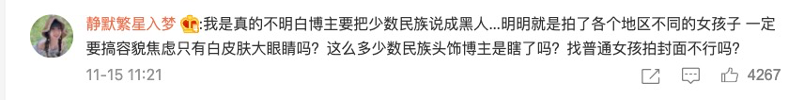

At the same time, a Weibo fashion blogger described the group of pictures like this: "Chen Man's early work "China Twelve Colors" is also her most famous work, Chinese women do not show China in her shots. The beauty of women, some are like black people, some are like Indians, in short, they are not like Chinese.”[5]

Some netizens expressed objections in the comment area, believing that the photos were only taken of "ordinary girls" and "girls from different regions", and should not only recognize "white skin and big eyes" in terms of aesthetic standards. However, the criticism from the media and netizens and the scope of Chen Man's apology all included "China's Twelve Colors".

The various controversies and tensions arising from the Chen Man incident in the field of cultural production and social public opinion have opened up a space for us to ask questions. These controversies essentially revolve around the issue of representation in China. That is, why can we say that it is legitimate (or inappropriate and problematic) to represent "China" in a certain way? Who is the subject behind "China" and who can represent "China"? Especially in the Chen Man incident, in what context should the representation of "China" be placed in order to generate a proper understanding and provide a basis for the establishment of a critical perspective?

We may start with the aesthetic evaluation of female images, that is, "good-looking". People think that the women depicted by Chen Man are not ideal women in the eyes of ordinary Chinese people, and this judgment seems to be based on public aesthetic preferences. However, the formation of such aesthetic preferences cannot actually be grasped only through the interrelationship between the West and the East, but is embedded in a broader, multi-level social power relationship.

What we call "the looks that Chinese people like" is not so much a reflection of some "authentic" Chinese beauty, but rather a female appearance feature that has been popular in the Chinese entertainment industry in the past ten years. Most of the most popular screen actresses have high nose bridges, double eyelids and chiseled faces, and these traits are more common in European and American looks than East Asians. Because of this, ethnic minority actresses such as Di Ali Gerba and Gulinaza are considered to have a "natural" advantage in appearance. However, only when the facial features of a specific group cater to the public's European aesthetics, will they be identified as a legitimate "exotic style" by the public. The ordinary people under the lens of "China's Twelve Colors" undoubtedly cannot be regarded as the exotic in the mainstream expression. Beauty is recognized.

When certain facial features are regarded as symbols of beauty in mainstream culture, they are becoming more and more popular in the cosmetic, medical and aesthetic industry, and even the so-called "Internet celebrity face" and "mixed-race face" are jokingly called. The transformation of the body certainly reflects the positive aspects of Chinese women's pursuit of beauty and body autonomy, but it is undeniable that the common goal of "transformation" also implies the operation of post-colonial cultural power in the field of body aesthetics.

The Europeanization of mainstream aesthetics has not received much criticism, while appearances and skin colors that undoubtedly belong to China are unexpectedly left out of the definition. why is that?

Shirley Anne Tate, a Jamaican sociologist who studies black women, points out: "Beauty is not merely a matter of the individual, nor is it something internal, nor is it 'race' neutral...Beauty, as 'race' It is socially constructed.”[6] Beauty is not a non-historical eternal thing, on the contrary, the concept and standard of beauty are formed in the social and historical process, and there is no authentic, prior to a specific social context aesthetic system.

From this, we can better locate the current controversy about several works of Chen Man. We do not oppose the critical perspective of Orientalism, but advocate further understanding of a series of disputes and their contexts in multiple center-periphery relationships. Among them, the gaze of the West to the East is an important dimension, which constitutes a set of relations with the West as the center and the East/China as the periphery.

But this multiple, intertwined center-periphery relationship also contains other multiple dimensions of power. As noted above, critics' misidentification and dissatisfaction with minority subjects and their representations mark a center-periphery relationship fixed on the basis of ethnicity/ethnicity/ethnicity and skin color.

And when some comments claim that Chen Man's photos of Fan Bingbing and other well-known actresses and himself are "normal aesthetics"[7], the demarcation between "normal" and "abnormal" and the "local" aesthetic norms they rely on , is also inseparable from a set of hegemonic social constructions. In commercial photography, as well as the representation of the wider mass media, the ideal image of women is urban, upper-middle class, developed region, main ethnic group, pale skinned, implying wealthy, not having to engage in manual labor, educated, and civilized and good quality.

Judgments based on "normal" essentially stem from a struggle over the definition of "normal." In "normal" aesthetic politics, China/Native is an empty signifier to be filled under the hijacking of sociocultural power. Although ordinary-looking women from different nationalities are undoubtedly part of the collection of Chinese images, this physical identity does not automatically translate into a legitimate occupation of the symbolic position of "China."

Ideal women are called "goddesses" in popular culture. However, the discourse of supporting goddesses contains multiple levels of social and cultural inequalities in regions, urban and rural areas, and ethnic groups. In Chen Man's photographic works and their controversies, there is not only the gaze and representation of the East from the West, but also the power hierarchy within the "Oriental" and the presence of various center-periphery relationships.

3. The Orient as Heterogeneity and as Aesthetic Object

In public opinion, there are also some people in the fashion and cultural circles who believe that the accusation against Chen Man is due to the Chinese public's inability to accept differences in aesthetics, or their failure to understand the "progressiveness" of the Western fashion industry's acceptance of Asian women's images. If the interior of the East is pluralistic, is it possible that there may be some kind of alternatives/alternatives within the West occupying the position of gaze? To what extent can the pursuit of difference and even progress in the fashion culture system justify the representation of the oriental image in Chen Man's works?

In the traditional mainstream Western aesthetic context, the facial features such as slender eyes that are more common in Asian groups are often attached to negative value judgments. A study in the 1990s found that Asian-American women were keen to change the shape of their eyelids and corners through cosmetic surgery so that they could break free from traditional Asian stereotypes such as "sluggish," "passive," and "narrow-minded" [8] ].

However, there is often a certain distance between the aesthetics of the western fashion industry and the mainstream aesthetics. Sociologist Georg Simmel believes that fashion, on the one hand, tries to provide some kind of universal rules, on the other hand, "satisfies the requirements for difference, change, and individuality", and the culture that shapes its own class and circle is justified. Sex [9]. Therefore, although the Western business fashion industry has always been accused of creating body shame and body anxiety, to a certain extent, the cultural appeal for novelty and difference has also prompted it to go beyond the existing aesthetic norms.

As a result, Western fashion image design sometimes goes against the mainstream in order to justify difference and the beauty of the fringe (as opposed to the mainstream/centre of the West) . Black, transgender, gay, female model Jari Jones's huge New York street ad for fashion brand Calvin Klein shows that even a person who belongs to a minority and has a voluptuous body can still Show off your beauty.

Presenting the image of the Other in the traditional mainstream society in a positive way is also reflected in some of Chen Man's works through the differentiation and choice of model images, showing a diverse China. However, we will find that in addition to this part of the expression of the relative diversity and heterogeneity of the East, works such as "Pride of Preservation" do not actually make an effort to get rid of Asian stereotypes.

The visual representation of the East as the marginal/other, but intentionally or unintentionally, engages with the existing Asian cognitive inertia, which is wrapped in great prejudice. It seems that it cannot be easily matched with Jerry Jones' bold expression. Apparently, fashion is not as "completely indifferent to the present standard of living" as Simmel put it. In recent years, stereotype accusations related to Western fashion brands have become common. The repeated appearance of these screened, shaped and "typical" images of Asian women means that the logic of cultural production in the fashion field does not break, but ultimately serves him. The fixation and structuring of user bias.

A critique of Orientalism in Western fashion quoted Andrew Bolton, chief curator of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in his essay Toward an Aesthetic of Surface: “Design. The teacher's intention is usually outside of rational cognition, and is less influenced by the logic of politics and more guided by the logic of fashion, pursuing a superficial aesthetics rather than cultural essence."[10] This is tantamount to claiming that, Cultural elements are just materials that can be used at will and can be collaged arbitrarily. In response, critics have sharply called it "a scribbled depoliticization rhetoric."

So, how to understand the political logic behind this "depoliticized argument"? In his article "The Utility of Aesthetics: After Oriental Studies", the Japanese thinker Kyoto Karatani offers a comparable case: when Westerners discovered ukiyo-e in the late 19th century, this Japanese Edo-period market culture shook France Impressionist painters, Ukiyo-e are also regarded as avant-garde works of art that surpassed Western painting. Kariya commented:

The French's praise of these arts is only aesthetic praise, they are nothing more than to absorb these things into their own art. This is only possible because the people who made them have been colonized and can be colonized at any time. Yet aestheticists often forget this, thinking that to bow down to the beauty of the other's art is to respect him as the equivalent of the other. [11]

Here, the culture/image of the East is presented as a dehistoricized and alien culture/image of the West. In both the Ukiyo-e example and Bolton's point of view, the East is nothing more than a "cultural exhibit" in the eyes of artists and designers (often from the West or serving Western employers), displayed in the grand museum sequence of the West, and used for Activate the creativity and vitality of the West itself.

Karatani further pointed out that the reason why the Orient can be transformed into a pure aesthetic object is precisely by suspending and placing the historical context on which this way of representation of the Orient depends, and putting it into “brackets”. In his view, the aestheticization of non-Western things, including Ukiyo-e, was a process that unfolded simultaneously with the expansion of the Western colonial system. And by putting in "brackets" some of the actual conditions of knowledge about the Orient—history, interests, power relations—an aestheticized, innocuous Orient can be praised.

Going back to Chen Man's creation, if we accept her interpretation of "China's Twelve Colors", especially her artistic commitment to expressing a diverse China and a China of ordinary people, then "Pride and Conservation" cannot be easily dismissed. Accepted as a footnote to the so-called difference in the aesthetic context of Western fashion. Only when the history and politics of the female images in the photos are taken out of the "brackets", and the colonial history, the yellow peril theory and the "squinting eye" are put into the eyes of the creators and the people being reproduced, can the photographer's lens really have the Potential for change.

4. Inside and outside the East, how is aesthetic liberation possible

By interpreting the sequence of Chen Man's works and their controversies, we try to connect with a larger social issue: How can the fairness and justice of cultural production be realized in the East and West and in the wider global and local contexts?

Structural inequalities between East and West in the cultural realm exacerbate a range of cultural landscapes, including Orientalism. Relying on the strong culture, art, and consumer goods industries, the West often enjoys hegemony over the recognition and representation of the East. This hegemony has led to the West's cognitive violence against the East, that is, imagining, piecing together, inventing the East with the West as the center, and even allowing the East to internalize this imagination, believing that the West can talk about the East more correctly and more qualifiedly than the East.

At the same time, as we have pointed out, this inequality does not exist only in the West-East set of center-periphery relations, it actually operates in a coordinate system composed of multiple powers. Just like our analysis of "Chinese people's aesthetic preferences" and Chen Man's related critical views, the aesthetic value of local society is also rooted in specific social and cultural structures, that is, social categories such as class, urban and rural areas, regions, and ethnic groups - these categories Both political-economic and culturally imaginary—constructing a multiple center-periphery system and, through their relative positions within this system, contribute unevenly to the aesthetic standards of “society”.

Therefore, aesthetic liberation means not only breaking the shackles of Orientalism, but also requiring reflection on the power relations behind various social constructions. It cannot be achieved through independence from other social fields, and cannot be achieved through isolation from the living history of the real world, because the establishment of aesthetic viewpoints and the senses and consciousness that people act on aesthetics take place in this world. On the contrary, only with the determination to remove all kinds of "brackets" and to be alert to any aesthetic stereotypes and exclusionary tendencies, can society - whether East or West - establish a truly autonomous and inclusive aesthetic form.

Perhaps we should expect to see richer images in the public sphere: women and men, plump and slender people, people of different ethnicities and sexual orientations, farmers and workers, people with disabilities. They can all be beautiful.

Welcome to subscribe to the WeChat public account "Mayfly Ghost" (ID: gh_ff416309254e).

References and Related Links

[1] People's Daily Online Review, "Dior's "Aesthetics" Rollover: Art Can Be Unpopular, But Not Evil, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzUyMTA5MDc1Mw==&mid=2247494720&idx=2&sn=e8173e7f793c150dbcdc184e3e79023f&scene =21#wechat_redirect [2] Weibo (ChenMan), https://weibo.com/1498522714/L2PijfFHO [3] Deep Focus DeepFocus, "Shangqi Rejected by Mainland China, Chinese Rejected by Chinese", https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/nC7UzC10rKHS9pGLat1iJw [4] RADII. November 18, 2021. Netizens Attack Photographer Chen Man Over Image in Dior Art Exhibit. https://radiichina.com/chen-man-dior/ [5] Weibo (FashionWeek), https://weibo.com/2481058012/L1zitlRLV?refer_flag=1001030103_ [6] Tate, SA, K. Fink (2019) Skin Colour Politics and the White Beauty Standard. In: Liebelt, C., S. Böllinger, U. Vierke (eds.) Beauty and the Norm. Palgrave Studies in Globalization and Embodiment. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. [7] Cultural Industry Review, "Chen Man's Works: Aesthetics can be Diversified, but Attitudes Can't Be Double-standard", https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/pleMnw-bka3XqhGfEEnIHA [8] Kaw, E. (1994) “Opening” faces: the politics of cosmetic surgery and Asian American women. In: Sault, N. (ed.) Many Mirrors: Body Image and Social Relations, pp. 241–65. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [9] Simmel, The Philosophy of Fashion, translated by Fei Yong and Wu Jing, Beijing: Beijing Culture and Art Publishing House, 2001. [10] Jiemian News, "From Dolce & Gabbana to Victoria's Secret Angel: How Does the West Imagine the East? ", https://www.jiemian.com/article/2643010.html [11] Pedestrian Karatani, The Utility of Aesthetics—After Oriental Studies, published in Ethnicity and Aesthetics, translated by Xue Yu, Xi’an: Northwest University Press, 2016.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!