308|What does a rock gym that supports bouldering for people with disabilities look like?

In "Mountains: A Political History from the Enlightenment to the Present", two French writers review how "mountains" as an image have been woven into people's social and political actions in different ways and intertwined with the larger process of modernization. It is a natural barrier, but it is also an excellent measure of the limits of human flesh. The image of climbers is embedded with key virtues of modern nation-state identity, such as strength, independence and tenacity. The conquering climbing aesthetics usually emphasizes the danger, challenge and terror of the mountain, and uses this to highlight the will of man to conquer nature.

–

Initially, artificial rock walls were just a product of mountaineering enthusiasts (usually white European men) who wanted to increase their training opportunities in the cold season. However, in the past decade or so, indoor rock climbing has gradually formed its own ecosystem. Artificial rock points of different materials, textures and sizes can be combined in strange ways to create climbing routes that do not exist naturally. In a completely artificial environment, the rhythm and style of the rock gym have become somewhat experimental, and the rock gym operation team, rock climbing route designers, rock climbing communities and larger spatial order structures (schools, shopping malls or community streets) have formed a new interactive relationship: Who is allowed to enter? Who can enjoy it? Since the 1990s, commercial indoor rock gyms have sprung up in the West, and more and more teams in China have entered the urban rock climbing industry to explore the above issues.

–

Based on his experience in indoor rock gyms, Luke Maxwell, the author of this initiative, emphasizes the neglected elements of conquering rock climbing: community support, non-competitive joy, and inclusion and celebration of diverse physical conditions. As a leg brace wearer and bouldering fan, he reflects on the unconscious "able-centrism" in the planning and design process of American rock gyms, and based on conversations with a large number of physically and mentally disabled climbers, he describes his ideal barrier-free rock gym.

Original author / Luke Maxwell

Original title / Design Proposal for an Accessible Bouldering Gym

Translation/ Xi'an, Shuyun

Proofreading/ Lin Zihao

01.Why is rock climbing full of obstacles?

Bouldering is a form of free climbing characterized by the ascent of low rock formations or artificial walls without the use of ropes or harnesses. By definition, people with physical disabilities who require physical support to climb are excluded. Bouldering was once less popular than sport climbing, but over the past few decades its popularity has been rising around the world.

Including in Chicago, all climbing gyms today have bouldering walls, and more than half are bouldering-only gyms. None of the gyms in Chicago have been designed specifically to make the facilities accessible to people with disabilities as well as those without disabilities. Disability exclusion is evident in nearly every aspect of the gym’s built environment : front desks are often higher than the heads of wheelchair users; mats on the floor used for climbing require footwork; there is almost no representation of people with disabilities among staff or community members; and bouldering is done without ropes by default are just a few examples of how these gyms are not inclusive. As a result, options for disabled climbers in Chicago are very limited. Specific programs designed to create climbing opportunities for people with disabilities are only allowed during certain times of the week or month (3-4 hours) in gyms that have ropes.

In the effort to achieve accessible bouldering, we need to rethink how we define bouldering and climbing. In line with Titchkosky’s (2011, p. 6) call for “denaturalizing seemingly ‘natural’ exclusions,” this accessible gym initiative questions the fundamental components of climbing—the sport, the gym space, the climber, and the categorization systems that define them . I have developed some suggestions through observing the barriers that exist in current climbing spaces and climbing and interacting with climbers with disabilities. Despite the exclusion, climbers with disabilities still find joy in the sport and form close communities.

In a typical Chicago climbing gym, we see a narrow, yet culturally influential definition of climbing—a sport in which mostly white, able-bodied climbers ascend or traverse walls designed for “normates” with the aid of their climbing shoes, chalk, and sometimes a safety rope (Hamraie, 2013). Several aspects of this definition are clearly limiting from the outset. The American climbing community has recently woken up to its lack of racial, gender, and sexual diversity and is pushing for new understandings of climbing that seek to change this (“The State of Climbing,” 2019). Yet, within the climbing industry and community, there is little that welcomes or takes into account the rich variety of physical and mental conditions of current and potential climbers. In turn, today’s typical indoor climber—white, millennial, and non-disabled—may have a hard time thinking about how accessibility issues relate to their sport (“The State of Climbing,” 2019).

In modern indoor climbing gyms, able-bodied climbers can experience physical challenge, trust, and creativity through their movements on artificial rock walls. However, the gamification of climbing and the able-centrism behind the design of gyms, walls, and routes make these experiences out of reach for climbers with disabilities. The climbing difficulty rating system was initially created by Austrian climber Fritz Benesch in 1894, and after many iterations, these guidelines became a complex system for classifying climbing sports based on able-bodied norms by the end of the 20th century (Mountaineering Guide, 2021). This system, and subsequent mountaineering, traditional, sport, and bouldering rating systems, not only correspond the difficulty of a route to the ability of some imagined able-bodied climber, but also come with judgments about “strong” and “weak,” “good” and “bad,” and “correct” and “incorrect” movements. In modern climbing gyms, there are routes set by a team of able-bodied “route setters,” each with a clear rating based on assumptions about who will climb and their ability level. Not surprisingly, routes designed for able-bodied people force disabled people to perform movements that are not necessarily possible or natural, so potential disabled climbers are excluded from climbing in gyms and are considered unsuitable for the sport.

Hierarchies established by able-bodied people also distinguish climbing with artificial aids from other climbing. For example, aid climbing, which uses mechanical devices to move upward, has a different hierarchy than free climbing, which emphasizes unencumbered physical climbing (although protected by ropes). Although there are no official hierarchies for specific climbing methods, free climbing is praised as "pure" and "unencumbered" because of its emphasis on the body of solo climbing. Free climbers like Alex Honnold (who climb freely without ropes) are praised as representatives of freedom and individualism, in stark contrast to aid climbers who rely on artificial equipment and are often the subject of climbing jokes.

A meme about aid climbing. In the picture, a young woman with the tag "aid climbing" angrily says "you always pretend to be better than me", while on the other side, three middle-aged men and women in tuxedos sit upright and look arrogant. They are respectively labeled "free climbing", "free climbing" and "bouldering". Source: Reddit

Climbers with disabilities who don artificial climbing gear, complex harnesses, multiple ropes, and are assisted by side-climbers or callers are automatically relegated to the bottom of climbing society (if they are not completely ignored). Their climbing is deemed worthless because it cannot be placed into traditional grading schemes, and they are seen as weak because they cannot climb seemingly "easy" routes. Many times, their unconventional, impersonal climbing methods are not even considered climbing in the first place.

02. Accessible rock climbing: What is rock climbing?

However, some disabled climbers have established disability-friendly spaces. Kareemah Batts is one such climber. An amputee, she created the first adaptive climbing workshop in New York City in partnership with Brooklyn Boulders, which eventually led to the formation of the Adaptive Climbing Group (ACG) (“Our Mission,” 2021). The Adaptive Climbing Group has since established partnerships with gyms in the greater New York area, Massachusetts, and Chicago. I have been climbing with the Chicago Adaptive Climbing Group for almost a year now, volunteering at their Wednesday night classes and being an adaptive climber myself. The climbers who attend these classes have a variety of disabilities, and the group tries to help them get up the climbing walls designed for “normal people” with specialized equipment. I use a calf brace to help me position myself on the wall and maintain control of my right foot. My own climbing experiences and those of other disabled climbers have allowed me to see not only more flaws in the able-centric definition of climbing, but also the potential that some participants have to redefine climbing style and sport.

In the adaptive climbing group, we like to rotate climbers and volunteers into pairs, and I use this opportunity to observe climbers with different disabilities in action and have some conversations with them about the meaning of climbing. My initial plan was to conduct some semi-formal interviews with the adaptive climbers in the group. This interview method allowed me to record their thoughts and helped me draw more empirical evidence-based conclusions. But later I gave up this path because I was not comfortable with the role of an interviewer to start a conversation with climbers. I turned to trying to observe their climbing and embed more abstract questions about climbing into our daily chats. This allowed me to avoid asking more intellectual questions like "How do you define or describe climbing" and instead use more everyday terms like "Do you like/dislike climbing?" or "What is your favorite part of climbing?"

The climbers' responses were illuminating and touched on many fundamental elements of climbing action and practice. As one climber described it (a woman I've helped climb with several times), her favorite part about climbing is the physical challenge it provokes. She described how climbing allows her to use her whole body, muscles, and other parts of her body, which is often overlooked in targeted therapeutic exercises.

Speaking of "whole body muscle involvement," I've noticed this myself a lot in climbing, as new movements force me to tighten certain parts of my body that I wouldn't normally notice. New muscle involvement is also very noticeable when I'm assisting. The main task of an assist climber is to coordinate movements with the lead climber, placing hands and feet, or providing back support and lifting support. This requires a certain level of mental acuity, physical coordination, effective communication, and pushing movements that are not involved in solo climbing. I've talked to other disabled climbers about this experience, and everyone's response is the same.

I further explored the nuances of this experience in a conversation I had with another climber during a break from climbing. He told me that, in fact, his progress in climbing was about “learning how to trust and use his prosthesis.” He described how certain movements forced him to use his prosthesis, and his initial distrust of it led him to overcompensate with other muscles, which quickly led to exhaustion. These climbers described climbing as an engagement and trust in their disabled bodies , which subverted the able-centered norm of what is “useful” or “effective.” Here, over-reliance on the able body is limiting.

My own experience as a co-climber and member of a team belaying seated climbers has also further challenged the stereotype that climbing is a purely individual endeavor. As I mentioned above, climbing with others as a co-climber requires precise communication and coordination, which reflects the collective nature of this style of climbing.

Of course, the job of a top rope belayer has similar characteristics, though they are less obvious due to their location on the ground. However, for a team of ground belayers, especially when working with a seated climber who needs help ascending, pulling down a handgrip, etc., it is imperative that they coordinate with each other and the climber to precisely control the amount of force required to pull on the rope. The physical focus required to balance the challenge with the level of assistance to the climber means that the climber and the belayer team work together as a collective unit to climb. These different forms of climbing are rooted in community, allowing for a continuity between community and climbing that many healthy-centric commercial gyms aspire to but often fail to achieve. In fact, “community” appears in the mission statement of nearly every gym I have encountered, yet I (and many other members I have spoken to) often feel a disconnect between the fierce individualism of these gyms and the “community spirit” they claim to foster.

My observations of adaptive climbing group members on the wall confirmed these conversations about challenge and community. They were also redefining what most climbers consider “good” or “strong” technique. These climbers taught me that shaking, shaking, fumbling, calling for support, twitching, resting, screaming in joy or fear, and conversation are all ways of trying to control the body on the wall that are powerful, useful, and beneficial. For these climbers, climbing is about more than narrow definitions; it’s about challenge, risk, trust, fun, community, creativity, novelty, and change.

Finally, a point that was repeatedly expressed to me by group members was that bouldering was out of their reach due to an unwillingness to accept a fall that their body might not be able to control or withstand. Many adaptive climbers were automatically excluded from bouldering due to the lack of rope support.

03. Create an accessible bouldering gym

Bouldering was my first introduction to climbing and it is my primary and favorite form of climbing. And, as I mentioned above, it is one of the forms of climbing that most excludes disabled people from climbing in gyms. Based on my analysis of the able-centrism of climbing grades and routes, as well as conversations with disabled climbers, I seek to reframe the current able-centrism of gyms to make climbing walls and climbing more accessible, either through tools or interpersonal support. I seek to focus on the built environment of the gym to show the most important aspects of climbing from the perspective of disabled climbers. Such a gym would acknowledge and celebrate collective forms of climbing and eliminate the hierarchical system that privileges non-disabled climbers.

Still, my proposal is only a starting point—it is rooted in real conversations and experiences with people with disabilities, and in exploring a fundamental understanding of climbing itself. My design approach is closest to the idea of universal design, which seeks to provide access to as many bodies and minds as possible (Hamraie, 2013). Of course, I am inevitably "biased"—I sincerely believe that everyone can have a great climbing experience, whether it is a high wall or a low wall, given the right opportunity. (In fact, many of the ideas proposed here can also be applied to top rope rock gyms.) This design proposal is a start in the long and iterative process of realizing this one person's dream.

Although the climbing experience begins before a climber enters the gym door, I will focus the scope of my design proposal on the sport environment that is most specific to the act of climbing itself. Therefore, this article will not discuss accessible pathways, tables, lighting, music, seating, parking, bathroom/restroom facilities, and other facilities such as weight rooms or yoga rooms. These elements of the gym environment are important points of contact for creating a sense of comfort and “dwelling” when designing for people with disabilities and have been well discussed in disability studies texts focused on accessibility (Bauman, 2014, p. 390). The relatively niche topic of climbing walls has not been covered in current texts on accessibility, so I will attempt to explore this.

The most notable features of the accessible climbing gym I advocate for are replacing defined or "set" routes with multi-angle free climbing walls (spray walls); eliminating the so-called "route setters" and establishing a "Climbing Staff" composed of climbers with and without disabilities to provide interactive support to climbers and assist them in using the facilities; and installing optional rope supports on all climbing walls.

I imagine a gym with “climbing staff” climbing alongside climbers, offering assistance, and ensuring the safety of all climbers in the gym. Scattered throughout the gym and wearing easily recognizable uniforms, climbing staff will assist in setting up rope protection systems and helping climbers design their own climbs based on the mechanisms I outline below. Crucially, the staff will be made up of experienced climbing individuals of all shapes, sizes, colors, abilities, and personalities. They will also observe, document, and have the authority to initiate redesigns of any part of the gym that is inaccessible to climbers. Experience with climbers on the ground and on the walls will make staff intimate and familiar with climbing spaces, fully understanding the entry points for improvement. I hope this will allow for ongoing design, and continuous improvement of the gym environment.

By engaging closely with climbers, Climbers will also serve as the glue that holds the climbing community together—the familiar faces, sounds, smells, and vibes that climbers can return to regularly and feel like they belong. This role will facilitate their efforts to foster connections between climbers, initiate more conversations, and build climbing relationships. Climbers will build a supportive atmosphere that celebrates diversity in the sport.

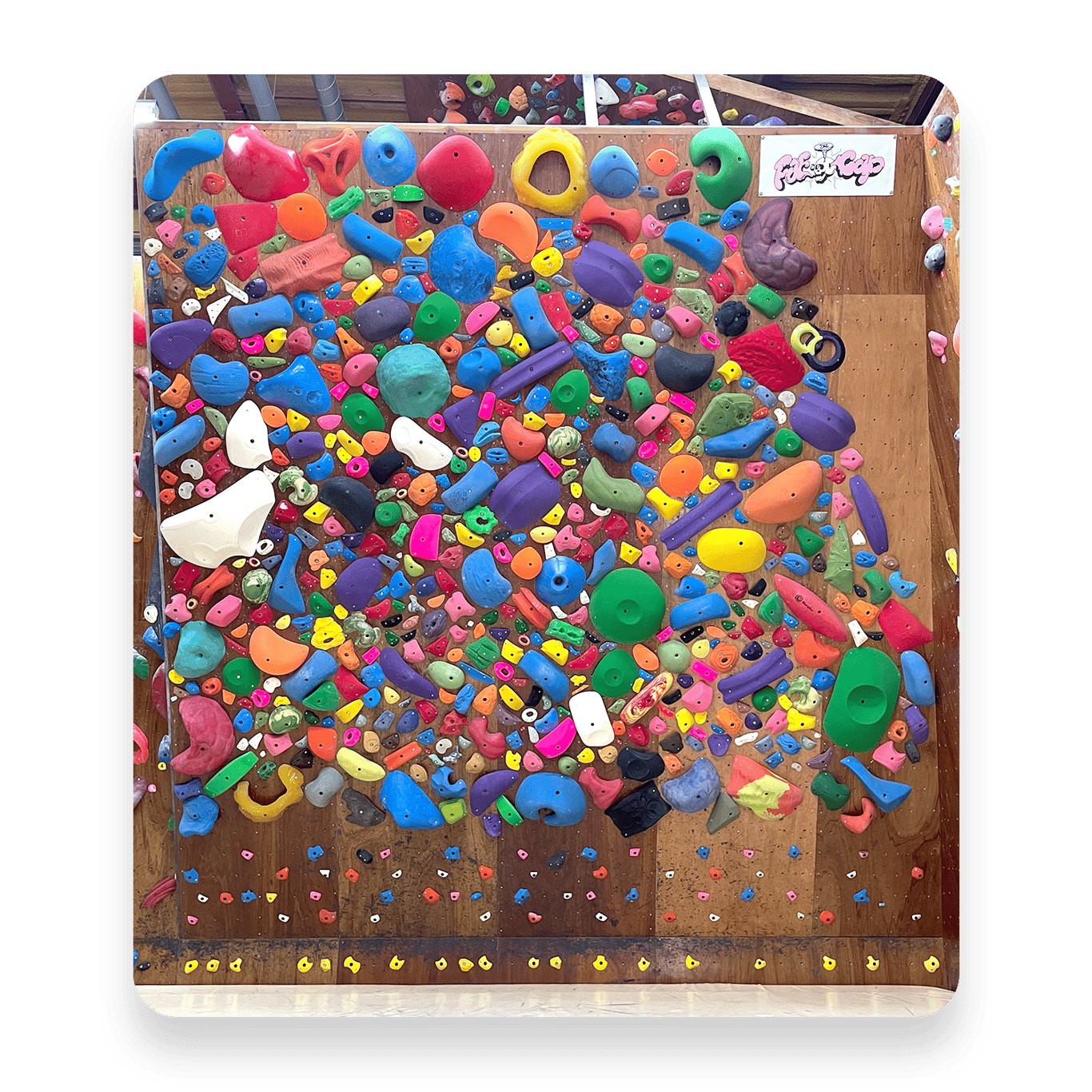

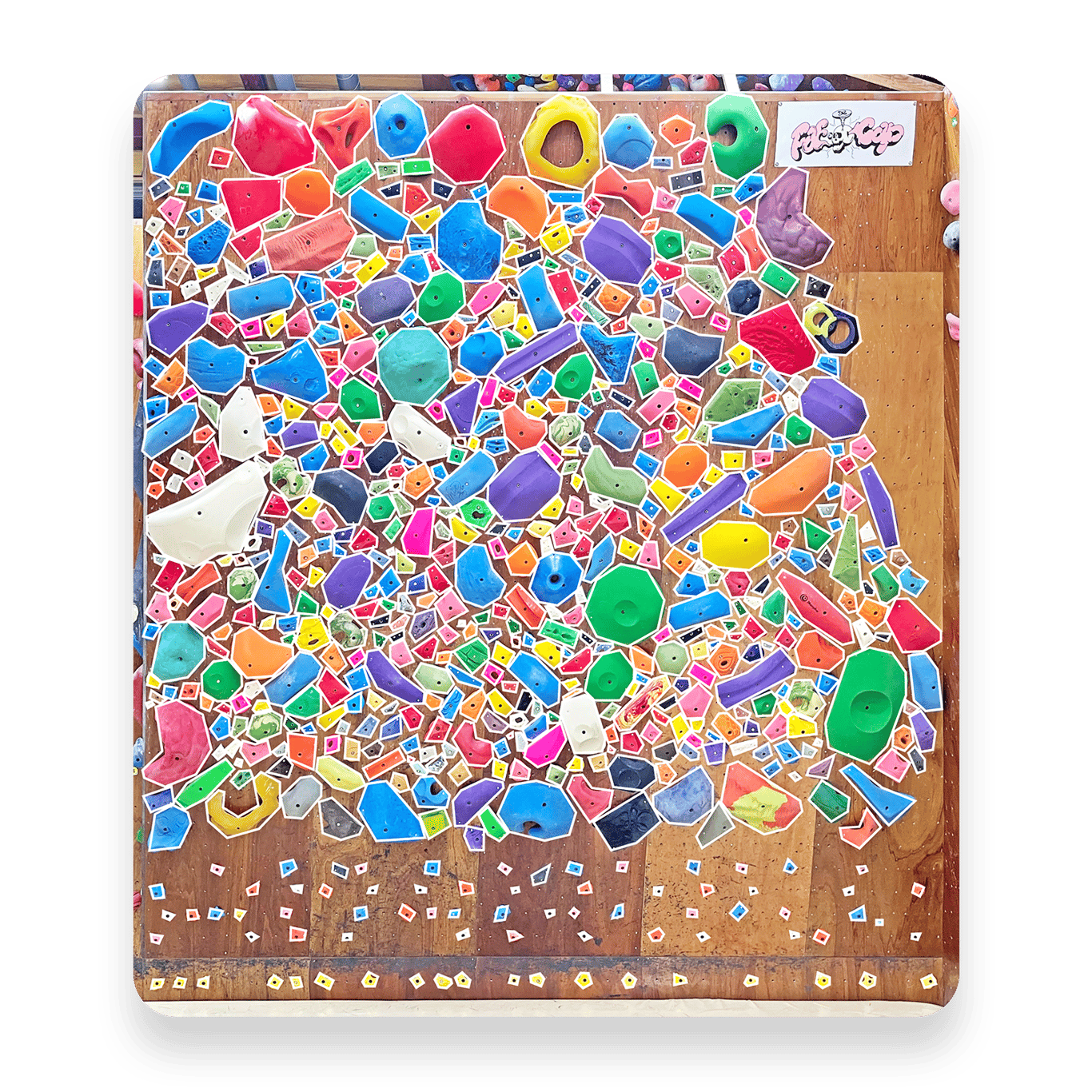

Another important component of accessible climbing gyms is replacing pre-set routes or boulder lines with spray walls. A spray wall is essentially a blank wall filled with moves that are curated based on variations rather than pre-set routes.

Free climbing walls allow climbers to become the ones who design their own routes, and determine the difficulty based on their own strengths and limitations. This therefore removes the need for a route-setting team and the assumptions about normative body movements and grading systems that go with it. In my opinion, as long as these walls can be experienced and climbed (which I will discuss next), disabled climbers must be able to set and share climbs that they feel appropriately challenge their bodies. The process of creating a climb is fun, while also adding a mental challenge to the act of climbing. Climbers can publicly post their climbs on dedicated mobile apps such as "Stōkt", "Eat Spray Love" or "Retro Flash" for others to try, and a sense of community can be fostered through the sharing of ideas and physical exercises ("Retro Flash", 2022; "Stōkt For Gyms", 2021). Another approach that is more in line with the traditional gym setting is to form a route-setting team with a variety of body types, but this will inevitably not be inclusive of all potential climbers' bodies. Why not just let disabled climbers design their own climbs?

For disabled climbers to design their own climbing routes, this means they need to be able to see, touch or hear the rock wall itself from the ground or on a mat, and the designed route needs to be recorded so that it can be climbed later. For visual climbers, this can be done by looking at the wall, imagining, testing and recording the route in a notebook or on an app like Stōkt (“Stōkt For Gyms”, 2021). Blind climber Matthew Shifrin has proposed a tactile method of planning a route with LEGO bricks before climbing (“Lego System”, 2020). As he describes it, “There is an order to touch. When you build with LEGO bricks, the scale is so small and so convenient that you can easily hold an entire building, an entire urban landscape in your hands.” (“A new system”, 2020, 00:02:41). The Lego brick mapping was done by Matthew’s tracker – the person who communicated with Matthew and guided his hands to the appropriate positions while he was on the wall – a role that could be trained to be filled by a rock climber. Although Matthew pre-mapped the route using randomly selected Lego bricks, it would be helpful to copy this approach and plan a set of Lego bricks for all the major hold types (crimps, pinches, pockets, jugs) and sizes. I recommend that gym rock climbers work with visually impaired climbers to design routes using Lego bricks and then record them on an app like Stōkt for easy review. I imagine all free climbing walls in a gym being equipped with large boxes of Lego brick pieces and boards for visually impaired climbers to design their own routes.

Free climbing walls can also use auditory cues to help visually impaired climbers locate holds during a climb when there are no climbers to act as callers. One possible approach is to design a climbing wall that links to an app that triggers specific holds in a climbing sequence to emit audible cues. When a climber grabs a hold, it will cause subsequent holds in the sequence to emit sounds, allowing the climber to determine their relationship to the next hold and prepare for the connection accordingly. Although no climbing wall I know of currently has this feature, I believe the technology is feasible - there are already many climbing walls that use apps to light up holds corresponding to user-set routes, such as the very popular moon board, "Kilter Board" and "T Board (tension board)". The configuration of auditory and tactile guidance will allow non-visual climbers to conceive, map and design climbing routes before they even get on the wall.

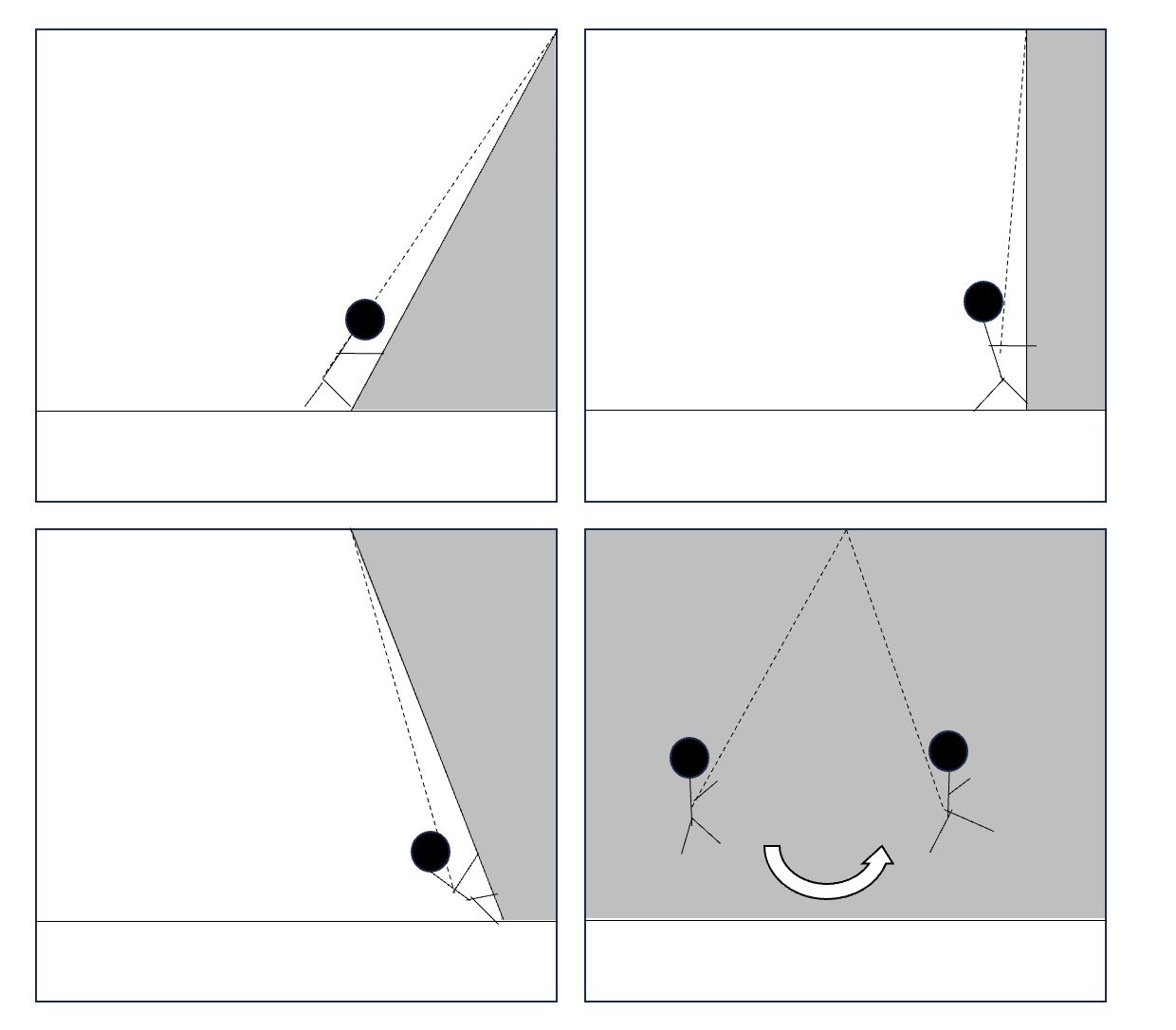

However, once a climber has designed a route, they must be able to attempt it themselves, and the gym should provide safety assistance, both in the form of physical and human support. First, the base of a bouldering wall is usually thickly matted, with wheelchair-accessible ramps between them that do not impede movement. Second, the wall must be high enough (ideally 15 feet, the maximum height allowed for indoor bouldering) so that a climber who prefers to use only his arms can start in the middle of the wall and still have enough room to perform 5-10 moves before reaching the top. Finally, each wall needs to be equipped with multiple ropes fixed to the top of the climbing wall to allow for multiple people to belay if needed.

The introduction of ropes to bouldering gyms may have completely redefined the bouldering experience, but it also brought with it a fair share of logistical challenges. Creative bouldering sequences often involve both vertical and lateral movements, overlap with other climbing routes, and extend through walls at different angles. For example, in a rope-free bouldering gym, it is impossible to have steep caves with walls parallel to the ground. However, slab walls (walls that form an obtuse angle with the ground), straight walls (perpendicular to the ground), and walls with angles as steep as 70 degrees (angles less than 90 degrees to the ground) allow climbers to start climbing from a seated position while still being protected by ropes in the event of a fall. The 70-degree angle is based on the fact that the climber's starting position needs to be far enough along the length of the wall (the hypotenuse) that the distance from the top of the wall can be less than the height of the wall - imagine a wall that forms a right triangle with the ground, with the wall being the hypotenuse and the height of the wall being the vertical distance from the top of the wall to the ground. On a 4.5m high, 70-degree inclination wall, the climber only needs to pull himself or herself to a starting position 30cm above the ground for the rope to catch him or her in space. This is not a problem for vertical and inclination walls: the distance from the climber to the top of the wall and the length of the rope are always equal, which means that any starting position above zero metres can be used for an alley-oop. Of course, falling from an inclination wall will swing the climber back and forth, but the belayer will be there to help cushion the force so that he or she does not then swing back to the wall with a large amplitude.

Additionally, an accessible climbing gym will also restrict rope-assisted traversal of a route to the left or right too much, as any fall will cause excessive lateral swinging, possibly resulting in injury. However, if climbers are properly informed of this limitation, I believe their own designs will reflect this concern for their own safety.

For climbers who prefer not to use ropes, the constant presence of ropes becomes a potential hindrance if hands or feet come into contact with them during the climb. To address this issue on angled walls, the ropes can be firmly secured to the outer edge of the climbing mat away from the wall. As the climber ascends the wall, they never come into contact with the ropes. On angled or straight walls, I envision the ropes being pulled tight against the wall and secured to the bottom edge of the wall to prevent movement, thus preventing the smaller risk of impeding the climber's movement. However, the rope's presence is minimized, and I imagine that since accessible climbing gyms foster a spirit of innovation, members will probably not be too resistant to incorporating ropes into their own climbs.

Climbers who need or prefer to use a rod-type ascender to climb walls in a seated harness may not benefit from the shorter durations of bouldering. The time it takes to get on and off the harness may be longer than the time it takes to get to the top of the wall. For this reason, I think gyms could use a separate rope system that is attached to the gym ceiling, rather than to any particular wall, so that climbers can climb for longer periods of time. The best location for this would be right in the middle of the gym. When a seated climber reaches the gym ceiling, they can look down at the gym and watch everyone climbing, while others can celebrate their climb.

Finally, in my opinion, accessible climbing gyms should offer rental options for wrist, knee, shoulder, elbow, hand, and ankle braces (even if they are crude) for those who need them. These types of body supports are no different than renting climbing shoes or chalk, and they help climbers maneuver along the wall. Therefore, they should all be available in the space, presented to new climbers as effective and necessary supports.

My design proposals only provide a few of the main ways that gyms can change or redesign the climbing experience. I believe that these changes, if they successfully evoke a sense of challenge, fun, risk, trust, creativity, and community among disabled climbers, will soon reshape the definition of climbing itself. When more bouldering gyms recognize disabled sports, group climbing forms, and the corresponding material support, ideological changes will also come - the meaning of climbing will no longer be limited to the scope of able-bodied centers.

Related Reading

Overcoming "disability"? Rethinking the toxic chicken soup in adaptive rock climbing

Make kendo an Olympic sport? — No, thank you.

Why athletes get political: Activism on and off the field

“Please look at my body” | An (un)usual viewing exercise

Reading about football: An anthropological guide to watching football games (Part 2)

Translator and editor

Xi'an, a neurodiverse social science researcher, is good at climbing walls for ten minutes and resting for an hour.

Shuyun, independent editor. Physical and mental awareness, care and courage, friendship and feminism, all converge in rock climbing.

Zihao is a man who is confused and growing wildly in the barrier-free urban field.

This article is translated and published with the author’s permission.

Use the literature

Bauman, H. (2014). DeafSpace: An Architecture toward a More Livable and Sustainable World. In 1758679713 1242171759 HL Bauman & 1758679714 1242171759 JJ Murray (Authors), Deaf gain: Raising the stakes for human diversity (pp. 375-401). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dawson, D. (2021). A Guide to the Different Mountaineering Grading Systems and What They Mean. Expedreview. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.expedreview.com/blog/2021/09/mountaineering-climbing-grades-part-1

Hamraie, A. (2013). Designing Collective Access: A Feminist Disability Theory of Universal Design. Disability Studies Quarterly. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3871/3411

How to Add Your Wall on Stōkt. Stōkt. (2021). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.getstokt.com/how-does-it-work-add-my-wall

Jacobson, D. (2020, February 28). Lego System Helps People Who Are Visually Impaired Reach New Heights at Rock Climbing Gym. The Carroll Center for the Blind. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://carroll.org/news/lego-system-helps-people-who-are-visually-impaired-reach-new-heights-at-rock-climbing-gym/

A new system could help blind people learn to rock climb. (2020). YouTube. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from A new system could help blind people learn to rock climb.

Our Mission. Adaptive Climbing Group. (2021). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.adaptiveclimbinggroup.org/about

Outdoor Industry Association. (2019). The State of Climbing Report. American Alpine Club. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://aac-publications.s3.amazonaws.com/articles/State_of_Climbing_Report_2019_Web.pdf

Titchkosky, T. (2011). The Question of Access: Disability, Space, Meaning. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Triangle Creation eTool. Desmos. (nd). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.desmos.com/calculator/1hg0vdgcf4

Latest articles (continuously updated)

Tron: Poverty and insecurity are the concrete and tangible reality for boys from the lower classes

Endless suspicion has a heavy impact on the daily lives of residents in low-income neighborhoods

France has never addressed discrimination against post-colonial immigrants

Baquet: Urban policy bureaucratization, community organizations exhausted

Misplaced floods: Pakistan floods and climate disasters in the global South

Anthropologist of the Week: Saul Tucker and the Anthropology of Action

What does a gym that supports disabled bouldering look like?

Welcome to keep in touch with us in various ways

Independent website: tyingknots.net

WeChat public account ID: tying_knots

【Highly recommended】Subscribe to the newsletter

Become tyingknots’ WeChat friend: tyingknots2020

Our contact address for letters, submissions and cooperation is: tyingknots2020@gmail.com

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More