Memoirs of a Loser 17: The Tragedy of Uncle Li

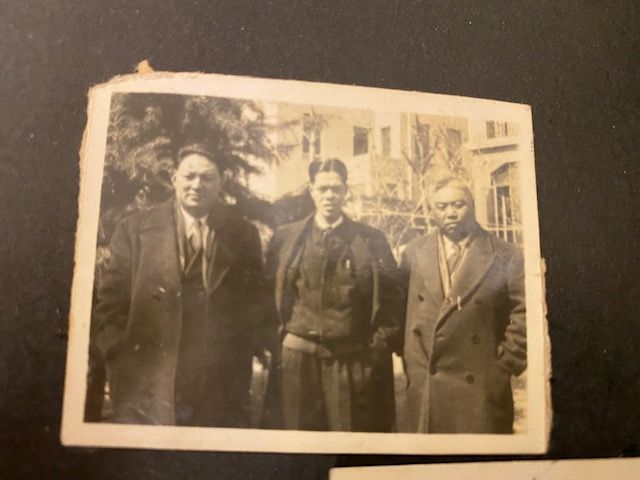

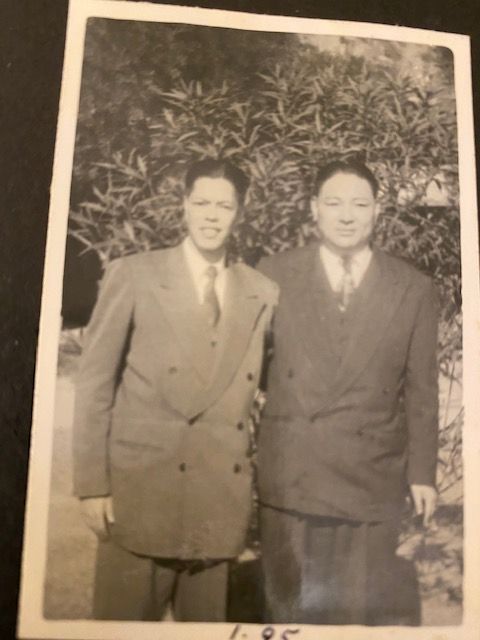

Qiu Kunliang's essay mentioned that Li Liuyao, who was very active in the drama movement in the occupied area, but "unaccounted for" after the war, reminded me from deep memory that my father and Uncle Li were excitedly talking in the living room at that time (I was seven years old). When I arrived at the limericks in the newspaper, I couldn't remember the first sentence, but the last three words were "Li Liuyao", and then I roughly remembered: "He is taller than the tip of a lamp, usually likes to sing Zhang Gongdao, and directs drama critics." I don't know what "Zhang Gongdao" is. He is active in drama activities and writes drama reviews, which was mentioned by Qiu Wen. Uncle Li is tall and fat, and he always likes to talk and comment on current affairs when he comes to my house. After the war, my family moved to Peiping, and he also brought his family with him at that time. He was still a frequent visitor to my family, but his name was no longer Li Liuyao. In 1948, my father and his family moved to Hong Kong from Peiping, and Uncle Li also came, but his family stayed in the mainland. Li Liuyao changed his name to Li Shutang and participated in the promotion, screenwriting and actor work of the Great Wall Company under the stage name of Zhao Song. His career in Hong Kong has not been a happy one. In 1960, his daughter Zhongzong came to Hong Kong from Beijing, both to seek refuge and to accompany her father. From then on, the two fathers and daughters often come and go together. After studying in Hong Kong for a year or two, Zhongzong was admitted to Shaw Brothers' actor training class, changed his stage name to Li Ting, signed a contract with Shaw Brothers, and filmed films such as "Folk Song Love". At that time, I was an editor at the Shanghai Book Company, and I invited Li Shutang to write a set of "Little History Books". His writing style was smooth, his writing was good, and he sold well. The fee also allowed him to barely make ends meet. Later, I started the magazine "Literary Companion" and invited him to write a novel, which was also quite wonderful. In 1966, when the Cultural Revolution broke out in the mainland, the leftist publishing industry in Hong Kong stopped publishing history books that were criticized by the mainland as "feudalism", and his small series died without a hitch.

Li Ting was half-red or not at Shaw Brothers, and she didn't know what grievances and losses she suffered. On August 28, 1966, she hanged herself in Shaw Brothers' dormitory, leaving a last word: "Dear father, you to live". Uncle Li did not attend his daughter's funeral. I went to see him and he was lying on the bed sighing. During the Cultural Revolution in mainland China, he was unable to communicate with his family in Beijing. Without a job and income, without Li Ting's salary, his livelihood has become a problem. Four months later, in January 1967, Li Shutang was also suspended with his daughter. I took care of Wu Ma's father, Uncle Feng Chengbi, for his funeral and buried him. I received his vast library of unwanted books.

At Li Ting's funeral, writer Chen Dieyi used the titles of several films she starred to strung together an elegiac couplet: "A song of love in a folk song, the original Jifang has flowed through the ages, and since then, the flowers are beautiful and dark green; Breaking the third watch will actually ruin the joy of youth?” At the funeral of Li Shutang, a friend Lou Zichun wrote an elegiac couplet, and it was gone: “Father and daughter are in the same order, some people kill without blood; friends and relatives are grieved, and the sign of heaven must eventually be returned.” Uncle Lou Guard this elegiac couplet in the mourning hall to prevent it from being taken down. And this elegiac couplet was finally not published in the newspapers. Lou Zichun wrote this elegiac couplet without any basis. But since there are no newspapers, let's leave suspense here.

Li Shutang is full of poetry and books, is keen on drama, understands the past and the present, and pays attention to current affairs. He often surprises four people in the living room. He is most proud of the era of "directing drama critics" under the Wang regime under the name of Li Liuyao. However, after the war, he not only failed to continue his career, but even concealed his own history. Did he really do something wrong during the fall? I don't think he thinks so. However, the general trend, how can individuals resist? He was also unhappy with filming and writing in Hong Kong, and the Cultural Revolution cut him off from his family and the land he cared about. A person with knowledge and talent, who ended up with such a tragic end, is certainly not the only one in the big era. Just because of the relationship with my family, this is just a note.

As for the drama activists who participated in important performances during the Wang regime, were they secretly connected with the anti-Japanese government in Chongqing? What kind of self-protection measures have the literary and art circles under the leadership of the CCP's underground party taken? I don't know for sure, but the family mutation that followed when I was nine years old made me feel a little bit of the complexity of the political situation of people in the occupied areas.

(Article published on May 31, 2021)

"Memoirs of a Loser" serial catalog (continuously updated)

- Inscription

- break through

- Inside the circle outside the circle

- murderous

- torment

- hurt

- turbulent times

- choice

- that age

- twisted history

- prophet

- Liberal final blow

- my family

- Occupied area life

- Paradise under the Wang regime

- Art and Literature in Occupied Areas

- Father and Occupied Area Drama

- Uncle Li's Tragedy

("Memoirs of a Loser" was previously serialized in "Apple Daily" and is now being continuously updated by Matters)

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More