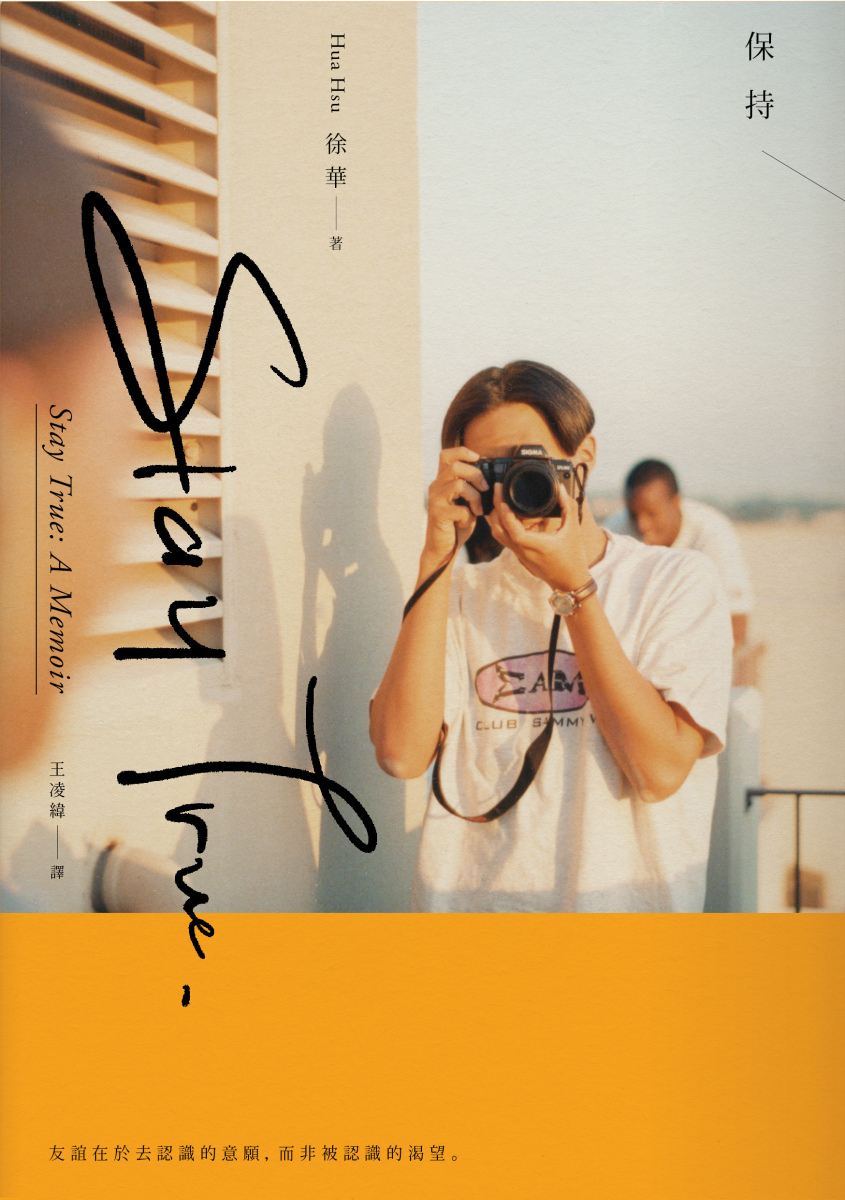

People" Memories, Youth and Friendship of Taiwanese Americans in the 1990s: An Exclusive Interview with Xu Hua, Author of "Stay True"

Text | Liu Wen (Assistant Researcher at the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica)

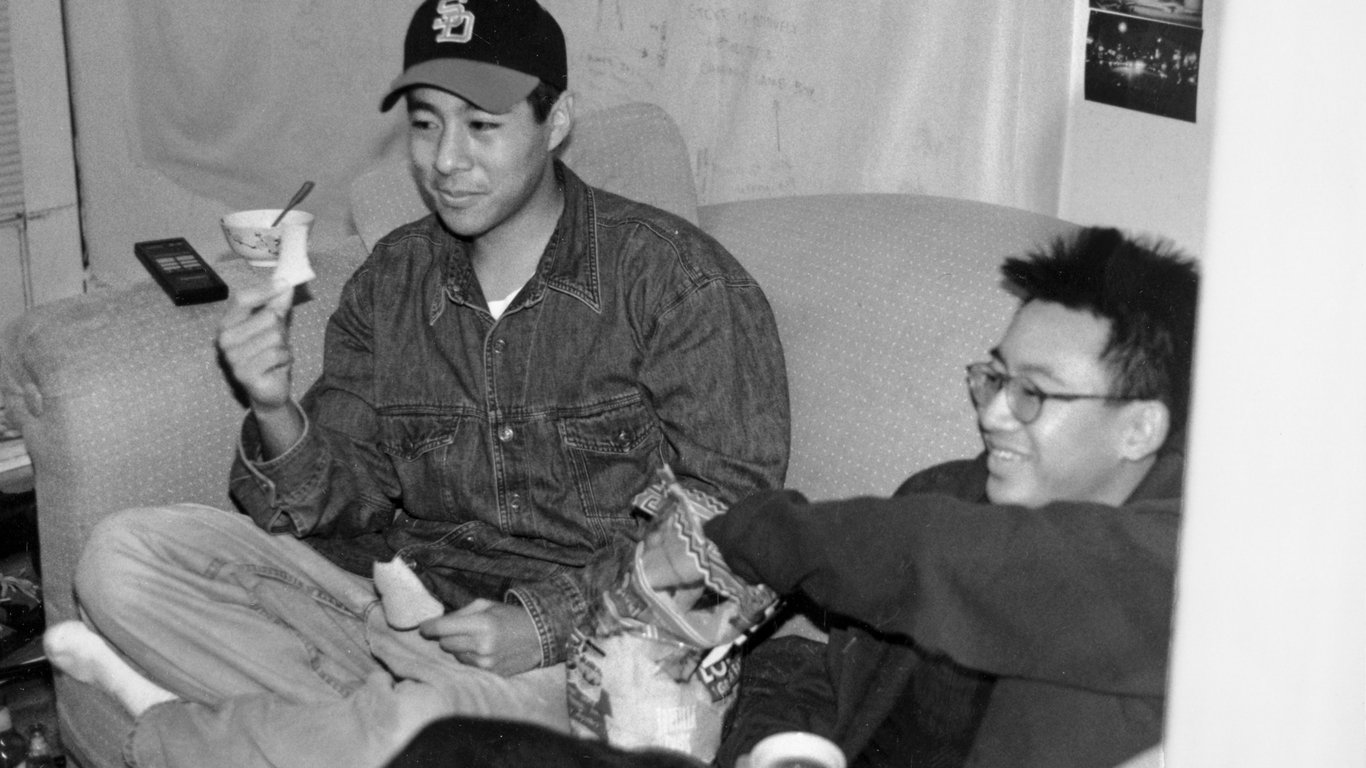

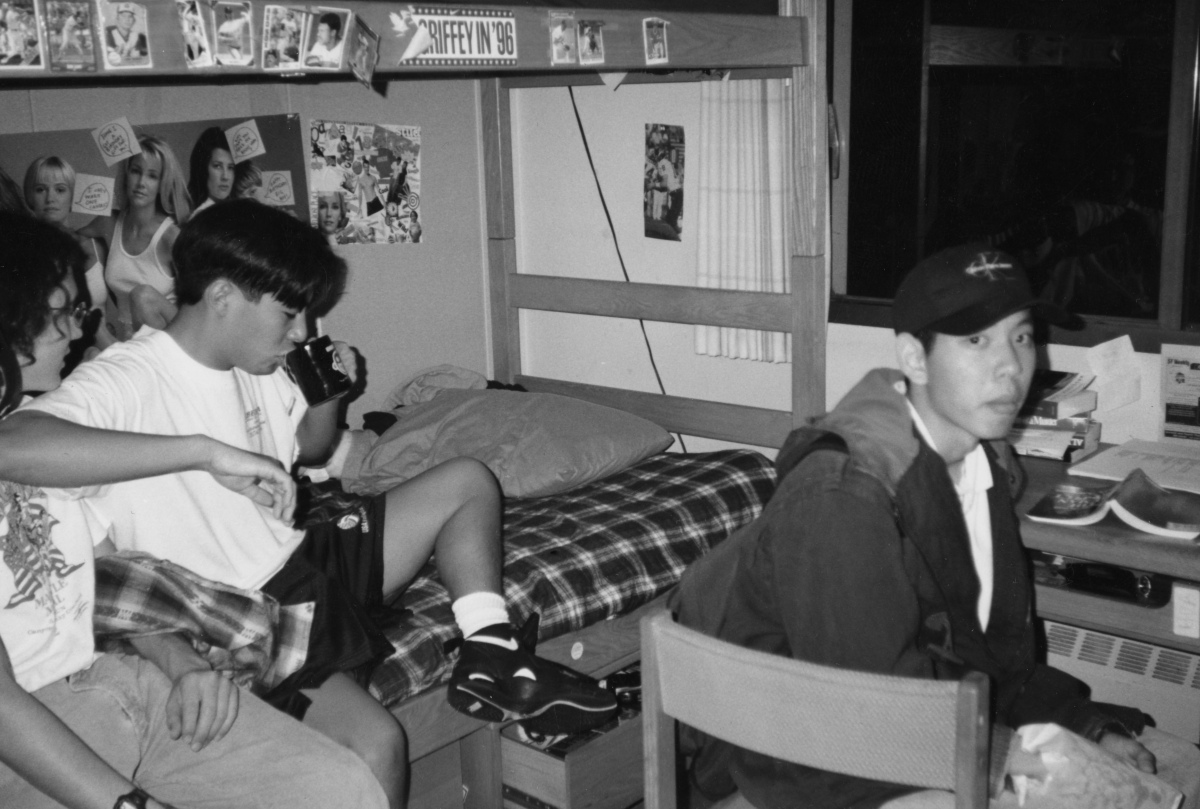

Xu Hua, a writer living in Brooklyn, New York, is a second-generation Taiwanese-American immigrant. During the interview, he was wearing a casual T-shirt, a denim cardigan, and black-rimmed glasses. There were posters of various independent bands hanging on the background of the screen. Born in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois in 1977, he grew up in Cupertino, California. This technology city, famous for Apple, also has surroundings familiar to countless Asians: bubble milk tea, beef noodles, and Chinese bookstores. Just like the Hsinchu Science Park where his father later stayed, it seems to be a mirror image of cross-border comparison.

Therefore, unlike most second-generation Asian Americans, Xu Hua is no stranger to Asian culture. Although he is already a university professor, married and has children, he still retains a youthful atmosphere, just like his writing tone, which is brisk and straightforward. His first autobiography, "Stay True," revolves around the story of his college experience at the Berkeley campus in California, outlining the unique liberal atmosphere, rapidly changing communities, and increasingly complex races on the West Coast of the United States in the 1990s. Politics, and the desire for community and friendship.

Because you are empty, and my empty past can never be forgotten

Sidewalk Band, "Gold Soundz" - opening lyrics of "Stay True"

➤About immigrants: "The first generation of immigrants only think about survival, and those who come later are responsible for telling stories."

Xu Hua's parents left Taiwan in the 1960s to study in the United States for graduate school. Like most young Taiwanese at that time, they would choose to immigrate if they had the ability. Xu Hua said that his parents had no special imagination about the United States. Immigration seemed to be just a natural path, which was completely different from his growth experience when he had more time to think about self-identity and existential issues. He said:

"They just wanted to further their education, and there was no such opportunity in Taiwan at that time. My grandparents were very curious people. They would subscribe to Life magazine and teach all the children English. Not because they thought all the children would go to the United States, but Because my grandparents are the kind of cosmopolitans. So my mother knows some things about the United States. I often ask her, are you excited to come to the United States? Are you scared? How does it feel? But they only say: This is part of my life, I will Just keep living, that's what our generation is doing."

In fact, for Taiwanese Americans of Xu Hua's generation, the differences between Taiwan and the United States are not as dramatic as the previous generation. When he was growing up, his father left the United States and returned to the Hsinchu Science Park to work in semiconductors, so he often spent summer vacations in Taiwan. He remembers that there were many foreigners in Bamboo Branch, especially those from the United States. He often goes to the science park library to look for Sports Illustrated. Even in the summer, he often just wants to ride his bike with friends or watch a baseball game. For him, Taiwan is a place with many beautiful memories and a country where he can see another side of his parents.

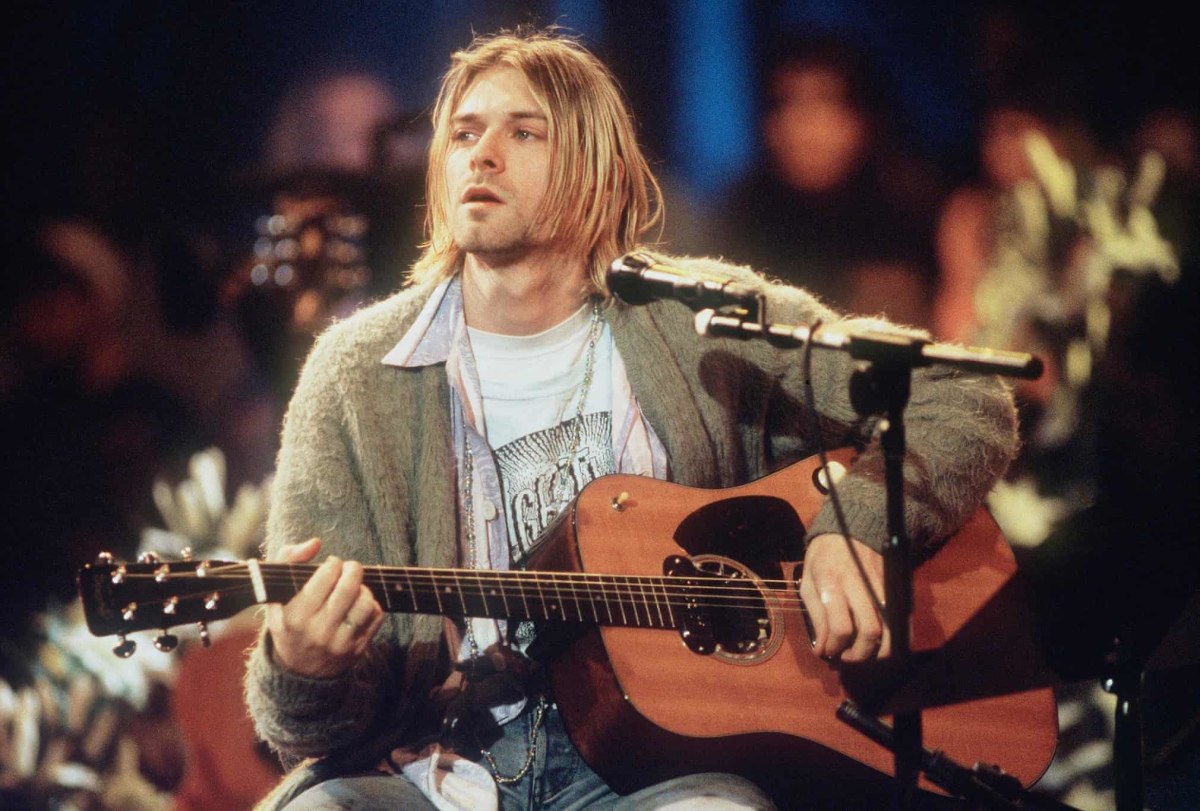

In the book "Stay True", Xu Hua recorded many conversations and letters with his father. I'm amazed that this generation of parents would write fax letters to their children about Kurt Cobain's suicide. Xu Hua's father said that the artist's death may be because he felt that the meaning of life has disappeared, and sometimes "normal people" can compromise real life. He wrote: "There is a dilemma in life: you must find meaning, but at the same time We have to accept reality again. How to deal with this conflict is a challenge for each of us. What do you think?"

Xu Hua's father often ended many of his letters with "What do you think?", which was very different from the authoritarian image of a typical Taiwanese father who only gave answers but did not ask questions. Xu Hua read the fax letters left behind when he was a child. In addition to the mathematical formulas his father taught him, there were also many philosophical speculations. He always felt magical and was grateful to his father for trying hard to establish a connection with him at that time. He said:

"He is a very curious person, so every time he asks me a question, he always asks why: Why did these two things happen? Why is this happening? After I had a child, he saw that my child collected Games or cards will also ask some philosophical questions, such as what is the meaning of Pokémon? I think my parents are more curious about things than many of my friends, maybe because they are more interested in young people in the United States. Their understanding is limited, so they like to ask me these things, accompany me to record stores or comic shops, and listen to me introduce new bands that I like.”

When Xu Hua was admitted to the University of California, Berkeley, he and his parents thought it was a good school worth attending. But Xu Hua's focus is not on Berkeley's ranking, but on its surroundings - the greasy and huge posa slices, the dimly lit leftist bookstores, the activists who don't have taboos speaking out for abortion and freedom of speech in the square, countless Qing’s used bookstores, antique shops and record stores - "Stay True" writes: "I am an American kid, I am bored, and I am looking for my kind."

➤About sincerity: “What does it mean to be sincerely yourself?”

The title of the book "Stay True" shows Xu Hua's persistence in "truth". For those who admire the philosophy of Jacques Derrida, the master of French deconstruction, reality itself is something worthy of doubt and dialectics. In the 1990s, the dazzling trend of critical thoughts such as postmodernism, postcolonialism, feminism, queer studies, critical race theory, etc., caused the old traditional "truth" to be questioned. People think that they will be placed on a clear path after birth, with a stable identity, socially regulated economies and roles, which no longer applies to the rapidly changing world under globalization. As a second-generation immigrant, Xu Hua is particularly sensitive to this issue.

In the book, he felt the difference between the two and his own uniqueness from his college friend Ajian. Ken is a Japanese-American. Even if they are both Asian-Americans, they are essentially different. Xu Hua, a slender and sensitive "non-mainstream" literary youth who likes independent music, wears vintage clothes, did not like Jian when he first met him because he was too "mainstream". He wrote in the book: "Jian is blatantly handsome, and his voice does not reveal any insecurity." Ajian's athletic figure wrapped in A&F casual clothes looks too sunny and confident. His girlfriend is A fair-skinned, "old-fashioned" beauty, he even likes to listen to Pearl Jam. Xu Hua wrote: "Ajian feels that he is part of American culture, which is something I can't imagine."

Aware of the gap between himself and mainstream American culture, Xu Hua has been trying to distance himself from such Americanness while growing up. Unlike most Asian Americans who are eager to be recognized by the mainstream, Xu Hua seems to have established a system of viewing American society from the margins very early, as well as a survival strategy of repeatedly traveling through various spaces. I asked him why authenticity was important to him. He asked, "Does this word exist in Chinese? How would you translate this word?"

Liu Wen: "Some, 'authentic', close to 'original' and 'real'."

Xu Hua: "Is this something that people are generally concerned about?"

Liu: "I don't think Americans care as much."

Xu: "I think caring about authenticity or authenticity is a very strange, very American phenomenon. I think it's because America is so amorphous. Its stories are full of 'old white men.' If you're African-American Man, if you're an Asian American immigrant, you can indeed be one of them, but there's a paradox there because it's not been that way for most of its history.

I think it just creates this desire in a lot of people growing up to figure out where they stand and who they really are in the culture. Because the so-called "America" has no nation or race. In other words, compared to most other countries in the world, the history of the United States is too short, which makes young people ask: Who am I? Who am I related to? Rather than just judging by yourself and your identity as an “American.”

But I think it's like a plane through which a lot of young people understand themselves, like where they are, where their community is. I think in the '90s, a lot of young people started thinking about this because pop culture was changing. This is a cliché, but the college students I teach now, they are still thinking about these questions: What kind of person am I? Is authenticity innate? Or is it something that you build around yourself over time? "

American pluralism advocates the co-prosperity of different ethnic groups and cultures, but looking at its history, the United States is a narrative dominated by white Christian values. This creates a crisis in "authenticity," especially for immigrants and people of color. Integrating into this society requires a considerable price - you have to give up some part of yourself.

Xu Hua's Jian conforms to the role of assimilation with mainstream America, but in the process of getting along with Jian, he gradually loosens his original binary classification: mainstream/marginal, immigrant/American , falsehood/authenticity.

Apparently, not all young Americans share the same concerns about authenticity. Being an immigrant, especially an Asian who is rarely represented in mainstream culture, must present another layer of difficulty. I asked Xu Hua how he faced the mostly extremely negative and lingering stereotypes of Asians in mainstream American culture when he was growing up. He said that when he was young, he had a lot of insecurities, but now he doesn't care so much.

He believes that some people will convert these senses of security into political mobilization or anger against the mainstream, while others choose to build their own communities, while he "doesn't mind staying on the edge." He said:

"I guess I like being different. Being in this marginalized group doesn't bother me, just having a community is enough. But like my students, young Americans today grew up listening to K-pop and watching Japanese anime. , these things have become mainstream in the United States. I think if there was a young Asian growing up in the United States, there would now be more role models and probably more confidence in their place in the culture.

But even though I grew up in the 1990s and didn't have these representative Asians, I didn't care that much, because it was impossible to fully integrate into the American mainstream. Also, because I spent a lot of time in Taiwan, I realized that I didn't need an Asian person to appear in an American TV series, because I would watch a lot of great movies and TV shows in Taiwan, all made in Taiwan or Hong Kong, This is enough. So I thought, oh, that's cool, there's this other world thing, and I like that better than the American thing. "

Because he can travel between different worlds, Xu Hua has another possibility of separation, or a route of escape, than other Asian Americans. For him, many problems do not require clear definitions, but a continuous dialectical process. He talked about the reason why the new book was named "Stay True", which was also a coincidence:

"The title of the book was a joke between me and my friends. It was not what I originally expected. My agent said: 'This book should be called 'Stay True'.' At first I refused because it sounded too much like a slogan. But now I can understand the title better because "Stay True" is a lesson and a concept in the book: there is no inherent truth to who you are, it is just a process of constant reinvention. You are always learning and reflecting on yourself. Therefore, being loyal to your own ideas is actually being loyal to the process of life, loyal to the people you meet, and loyal to change.

When I was younger, I imagined that there was a real me somewhere and that I would be complete when I got there, but now I am more accepting of things that are constantly changing. I feel that the only truth that every human being is born with is our values or hopes. While we may never fully realize our own hopes, or the moral standards we set for ourselves, our truth is what moves us in that direction. Just like when you were young, you looked at your parents and thought that one day you would become an adult, but it does not mean that you will suddenly become an adult at a certain time. In the United States, you can enter a bar at the age of 21 and rent a car at the age of 25. Society says you are an adult. But I am 46 years old, but I don’t necessarily feel that I have grown up. We are always in a state of unfinished business. "

阿健曾經開車繞遍整個聖地牙哥。就為了找一張珍珠果醬樂團的《傑瑞米》單曲CD,因為裡面有首叫〈黃色信封〉的歌。徐華盡其所能翻白眼,因為他認為那首歌顯然在抄襲吉米.罕醉克斯的〈小翅膀〉,但最終他們達成妥協,他們會坐在立體音響前恭敬地聆賞〈黃色信封〉。➤About youth: "The present is a burden, we live in the future. It is this small immortality that young people are pursuing."

The core of "Stay True" is a story of friendship. After Xu Hua and Ah Jian attended a party, Ah Jian was unfortunately killed and separated forever. Writing became a way of mourning and Xu Hua's way of allowing herself to move on. The world continued to go on, and Xu Hua also entered the doctoral program, left Berkeley, and moved to New York, the place he yearned for. In this big city full of new experiences and excitement, he wrote himself into the past.

Those records and smoking rituals could no longer carry his memory and longing for Ajian. He had to create his own narrative. Xu Hua said that even though this book is a memoir, he is not writing about himself. This book is about Ajian:

"The day after Jian was murdered in 1998, we discovered that everyone was coping and mourning in their own way. I started writing everything down. I wanted to record all of our jokes and daily conversations because never again There was no one with whom I could exchange memories, so I wrote everything down. I kept recording for many years, and I didn’t regard it as my own story. What I wanted to write was the story of a period and a group of people. It’s also a story about grief, loneliness, college, and how to escape from those things.”

"Towards the end, someone asked me about my family. They asked: How does your family express emotions? Because that's where we learn how to process emotions, how we learn how to deal with difficulty or trauma. I think , in order to make this book more meaningful, readers must understand my family, know who I am, etc. So I started to write about my family and myself."

"I find it easy to write about my family, but it's very difficult to write about Ken and that period of life because my relationship to it keeps changing. It feels like I'm trying to get back to something that's gone, that moment, that period The time and his loss were so painful that it was very difficult and very sad to write about it again. That was also the challenge of this book. I never had a goal, I just thought, let's see what's here. But when I look back, my goal was just to spend a little more time in the past, I just wanted to write myself back in time.”

Fearing that these memories would fade over time, Xu Hua found himself spending a lot of time searching for Ajian's name, evidence of his existence, and about the three strangers who hijacked cars with guns. The absurdity of this incident makes it even more difficult to digest and accept. In the book, he did not place Jian's murder in the context of American society's violence against Asians. Instead, he regarded it as the transience of life ("It's not a [hate crime]... it's just some... Fucking shit happens.”).

This way of writing also makes "Stay True" different from other second-generation Asian-American writings. There are no stereotyped immigrant parents with a sense of distance in the book, there is no cultural gap between generations, there is no homeland that cannot be returned, and there is no suffering as a racial minority, but it is full of a more universal nostalgia for the 1990s and friendship. mourning and yearning.

Xu Hua said that he wrote this memory in the form of a memoir because he wanted to experience that world again. Its sadness also included the happiness it once brought him. This may be Xu Hua's way of "keeping it sincere" to himself:

"I'm not a very creative writer. I've read some novelists say they created a world that they couldn't control, a world where everything happened for a reason. I've always felt that way of writing It's crazy, I can't imagine it.

But when I finally figured out how to write about what it was like to be a college student in 1996, I felt like I could write about this world and then walk around in it. That's what I want, I just want to walk around in the past and not just feel sad. I want to take a walk in the past and appreciate it one last time knowing what will happen in the future. "

Xu Hua quotes historian Edward Hallett Carr’s “What is History” at the beginning of the book: “Only the future can give us the key to interpreting the past; and only in this sense can we talk about a This is the ultimate historical objectivity. Historical justification and interpretation simultaneously enable the future to be understood through the past and the past through the future.”

Xu Hua wanted to write not just about the past, but about the future. But in order to find clues about how to move forward in the future, it is necessary to reinterpret the past and find a place in the heart where these unsolved mysteries can be placed. Just as the entire book continues to circle between the past and the present, his dialogue with his parents allowed him to discover the source of his curiosity about the world, and his disregard for his marginal position also allowed him to write broadly about the experiences he encountered in the 1990s.

➤About history: Have you seen yourself in history?

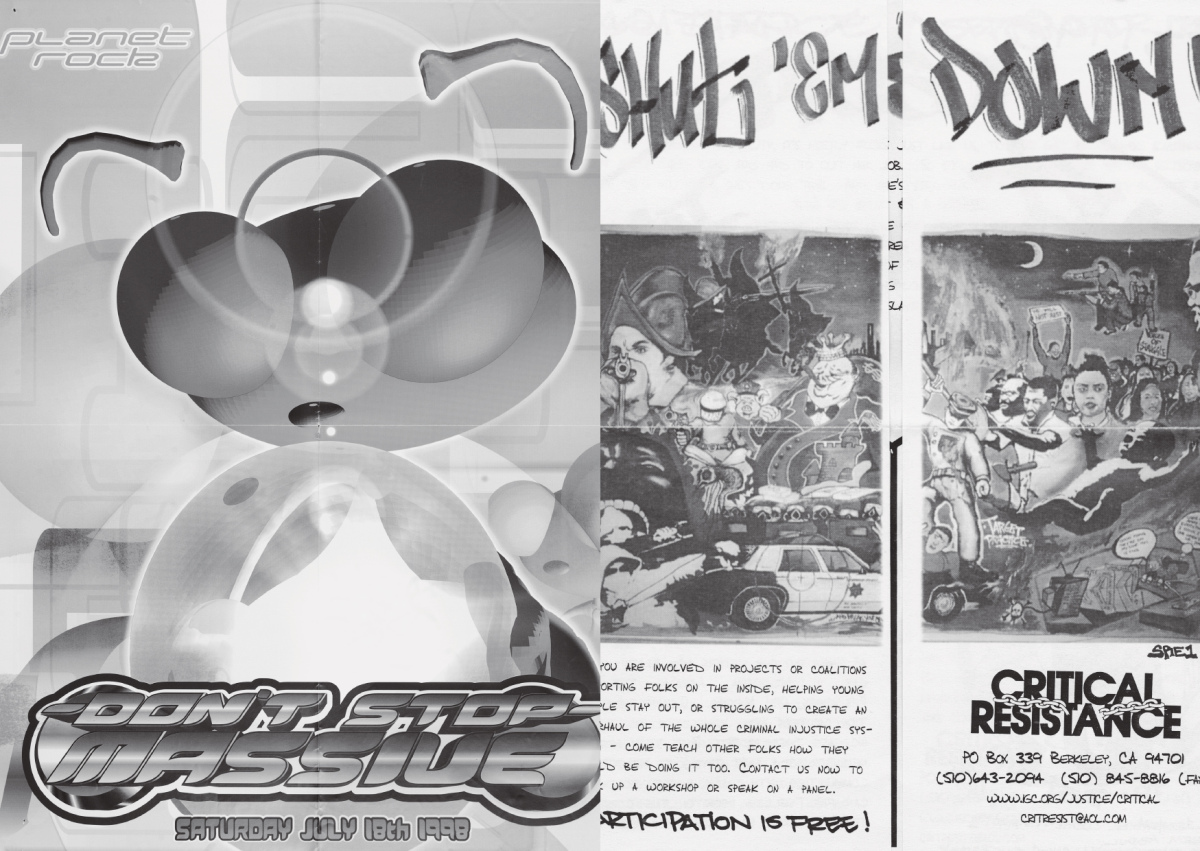

"Stay True" does not shy away from politics. The world that Xu Hua weaves through memories also includes the racial justice initiative on the Berkeley campus at that time - Yuri Kawauchi, a social activist who skipped class to join the social movement. Kochiyama and Grace Lee Boggs, and his own participation in the tiny revolution that began with editing Asian American zines.

He said that in the mid-1990s, many important issues revolved around affirmative action, bilingual education, and anti-police violence. As the immigrant population increases, language becomes politicized and people become aware of the problems in prisons in more countries. This kind of thinking about racial justice also made Xu Hua start to self-examine "whether he still opposes the death penalty" after learning that Ajian was killed by others.

But for Asian Americans at the time, their place in the racial debate was not necessarily clear. Just like the issue of bilingual education, it has a greater impact on Spanish-speaking people in California. In the ongoing affirmative action debate, even Asians have become representatives against affirmative action in admissions. In summary, whether it was in the 1990s or now 30 years later, the position of Asian Americans in the American environment continues to confuse many people.

Because campus political activities emphasize "affiliation" and "unity," Asian Americans on the margins also have a voice and a position of solidarity. Xu Hua said:

“Berkeley was a place where a lot of students would be drawn into political debates, so that was a really important time for me. I started to see the broader historical connections and how the black movement inspired Asian Americans. How the movement, the term Asian American, coalesced out of political struggle. It's not all about culture, it's not all about shared history, it's about the political choices we made.

I never knew where the term (Asian American) came from, it must have been invented and purely for political reasons. It was helpful for me growing up, going to marches about police brutality or prison industry complicity and seeing how it affects all communities. It's clear that incarceration numbers are increasing among Asian immigrants, just like African Americans. "

Even though Xu Hua's father often called himself an "oriental guy", he had no sense of connection with the new identity of Asian Americans. However, after Xu Hua participated in the Asian American social movement, he discovered that his father, who majored in science and engineering, had also He is a "leftist". He wrote in the book that his parents were concerned about the issue of Diaoyutai sovereignty when they were young, and often drove long distances to have meals with "activist" friends. They were even banned from returning to Taiwan for about 20 years because of their criticism of the Taiwan government's stance. During the interview, he picked up a yellowed magazine and said:

"There was an Asian-American magazine called "Bridge" that appeared in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, and the editors were all Chinese-Americans. One day my dad and I were talking about this, and he actually said, oh, these are what we I had them all, but I gave them away. I was like, why do you have this? These were for Asian leftists in the 1970s. He said, we have also participated in this wave of cultural movements, but what we focus on It’s not anti-Asian racism, but other issues within the larger international framework of being Asian Americans or Asians in the United States, such as anti-war, anti-imperialism, and other more transnational issues.

After I was born, these social issues turned towards domestic racism, state violence and other aspects. This realization is why I wrote about my parents in the book, because their experiences are part of Asian American history. When I was in college, I did not place my parents in this macro-political context. Then I thought, ah, they are actually a central part of it. "

The intersection of times gave Xu Hua and his parents different understandings of Asian politics, but through writing, the historical ruptures were reconnected. Different from the "depoliticization" narrative of the immigrant generation, Xu Hua's writing enriches our imagination of Asian Americans before the term appeared in the 1970s. The core of this book is the same. From an emotional perspective, Xu Hua and his parents may have the same curiosity about the world, even though they were born in very different eras.

I am very interested in Xu Hua’s teaching experience at Bard College in New York. It was a very radical, progressive place, so what are the trends in contemporary Asian American movements?

He believes that in the United States, because people still draw boundaries based on skin color and understand race in black and white, racial politics is still at the core of contemporary times. Of course, we can complicate racial class as we please, but in the United States, “anti-blackness” is the clearest and single form of oppression and dominates mainstream discourse. Xu Hua mentioned:

"For other minority groups who are not African American, it has always been difficult to solve this problem. For example, for Latinos or Asians, many times our experience cannot be fully integrated into the framework of 'anti-blackness,' but It is almost impossible to transcend this discourse. In the United States, many social movements still revolve around speculation on race relations.

I think the most interesting thing in recent years is the transnational dialogue, such as what "Breaking Earth" (Taiwan's left-wing online bilingual magazine) is doing. Whenever I read this, I think about these conversations that didn’t exist 20 years ago. But now, people have more awareness that Asians have a dominant role in global capital. No experience in this era is homogeneous, and different domination techniques will play their role in different environments. I think this is what really excites me.

I have been teaching Asian American literature for almost 20 years, and almost all of the students in my class are not born in the United States. They are no longer interested in racial issues in books, and they are more concerned about issues of displacement or transnational communities. Diaspora is no longer just an academic gimmick, but these networks and contexts can actually be seen through the Internet. "

Xu Hua's answer also reflected his experience of growing up transnationally, because having different worlds prevented him from locking himself into a single identity framework. What he is looking for is not the standard answer or "truth", but as he writes in the book, just a small group of people who can analyze movies with him, smoke cigarettes, and drive a long car just to eat sweets. Circle, discuss philosophy. What he is looking for is actually friendship itself.

《貝瑞.戈第之龍拳小子》是一部功夫喜劇,主要由黑人演員演出,主角叫李羅伊.葛林(Leroy Green),亦稱李羅伊小龍(Bruce LeeRoy)。徐華跟阿健都非常喜歡《龍拳小子》,他們甚至有翻拍自己版本的計畫。阿健先注意到巴斯達韻的歌曲〈危險〉(Dangerous) MV玩了《龍拳小子》的梗。➤About friendship: “Friendship consists in the willingness to know, not the desire to be known.”

The Beach Boys' "God Only Knows" hints that there's more to love than love. I can't find these emotions in the song itself. Could that be in the lyrics, the sad lyrics about two people growing apart and rediscovering their purpose in life?

——"Stay True"

In 1994, Derrida published a book about friendship, "The Politics of Friendship" (The Politics of Friendship). He believed that "friends" are an indispensable conceptual figure in philosophical speculation. Philosophers are not sages who meditate alone in the mountains, but because they have a group of friends and form a small society, philosophical thinking can take place.

The modern atomized society makes such opportunities increasingly rare, and the chemical reactions of relationships easily become the background of other grand narratives. Derrida mentioned that the intimacy of friendship comes from people seeing themselves in each other's eyes. Xu Hua’s profound thoughts on friendship also led him to place friendship at the core of his memoirs:

"The reason why I wrote this book, and the reason why I was drawn to the theme of friendship, is because when I think about the things we learn when we're young, it seems like we're learning how economics works, or how politics works, or how literature works, but we're really just learning how Spend time with other people. That's the nature of college, you learn some skills and how to think, but you also learn how to find community or form community, and that's what I was looking for.

Many young people are looking for a community, some join social movements, some start bands, and we are always curious about what people who share my interests are doing. For me, I just felt like I was really, really sad that Ken was gone. I'm not sure why I haven't been able to get out. Of course it would be hard if something terrible like this happened to someone close to you, but I found that it lingered and affected every new person I interacted with.

I often wonder, am I a good friend? One of the reasons why Jian can't let go is that I worry that I am not as good to him as I thought. Maybe we are not as close as I thought, maybe I did not give him the return and response he deserved. I worry that I've never been a good friend because I'm suspicious by nature or because I'm stuck in the past.

There are many songs about love in the world, and there are many books about love, but friendship is not like this. This isn't a well-explored subject, so I wanted to explore it. I remember I would listen to the music and think, ah, I feel this way about him, but I wasn't in love with him the way the song describes it. I suddenly discovered that there are not many songs about friendship, but most of the songs are based on friendship. Like the Beatles, they were all friends, but they couldn't sing about friendship.

I thought a lot about what happens when a person has friends? How does friendship change a person? How are your friends affected by you? How does friendship reorient your sense of time? Being bored with friends is a completely different feeling than being bored alone. I guess that's why I wanted to put friendship first in this book.

Of course, this book is about a lot more: what it's like to be Asian American, to be American, to be a young person. I always thought this was just a book about tragedy and grief. When I realized that it was actually a book about friendship and youth, I realized that this book helped me a lot and gave me the opportunity to explore other themes. "

Xu Hua's guilt for Ajian's death made him unable to let go of the past. Perhaps this was also a kind of survivor's guilt - why wasn't I the one who left? Although his narrative is full of confusion and uncertainty, his writing is full of compassion, nostalgia and tenderness. His writing is not pretentious and is as sincere as the title of the book. With detailed memories full of various sensory experiences, he lays out the huge background of the times, allowing people to immerse themselves in the world of the book even if they have not experienced it.

The background of "Stay True" is a unique story. However, it deals with the privacy of human emotions, but it is highly universal and can arouse empathy. It reminds us how the people we met in our confused youth allowed us to see our truer and more vulnerable sides; it reminds us that loss is sometimes unpredictable and unreasonable. However, if you carefully recall the painful past, you will be rich in surprises. Those moments of youth, full of dreams and curiosity about the world, have never left us. ●( The original article was first published on the Openbook official website on 2024-03-07)

Stay True

Stay True: A Memoir

Author: Xu Hua Translator: Wang Lingwei Publisher: Twenty Zhang Publishing [ Content Introduction➤ ]

About the author: Hua Hsu

Born in Illinois, USA, in 1977. He is currently a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine, a professor of English at Bard College, and an executive committee member of the Asian American Writers' Workshop. He has served as a fellow at the New America Foundation and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, and has written for Artforum, The Atlantic, Grantland, Slate, and The Wire. .

Xu Hua's parents are both from Taiwan. In the era when Taiwan's semiconductor industry was taking off, his engineer father chose to separate his family from Taipei and the Bay Area of California for better career opportunities. He took advantage of the summer vacation to visit Taiwan and put down roots in both places. As a second-generation Taiwanese, he wrote down his thoughts and confessions about immigrant culture, American values, and identity in writing. This book is his first but blockbuster attempt. The true and sincere account has made it one of the major publications in the United States in 2022. Media Book of the Year, and won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2023 and the first Pulitzer Prize for Autobiography.

He is also the author of the academic monograph "A Floating Chinaman: Fantasy and Failure across the Pacific". Currently lives in Brooklyn, New York with his family.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More