副業是在香港中文大學教書,主業是玩貓。

"Hong Kong Lesson 1" 15. Does Hong Kong really implement the separation of powers?

One of the paradoxes of Hong Kong politics is that officials who are also extremely influential in Hong Kong can have extremely different understandings of Hong Kong's political system, so that political debates often do not even have the most basic consensus. In 2015, Zhang Xiaoming, the former director of the Liaison Office of the Central People's Republic of China, claimed that the system of separation of powers in Hong Kong was not implemented, and that the chief executive had a legal status detached from the executive, legislative and judicial, which aroused heated public debate for a while. Some media have dug up the past remarks of the two Chief Justices of Hong Kong's Court of Final Appeal, Li Guoneng and Ma Daoli, who have clearly stated that the separation of powers is an important foundation of Hong Kong's political system. When a media interviewed Legislator Ma Dao about Zhang Xiao's remarks, he responded by citing the provisions of the Basic Law on judicial independence and equality for all.

Before explaining why their understandings differ, it is necessary to clarify the meaning of the separation of powers. Separation of power in political science refers to the dispersal of public power among different agencies in order to produce checks and balances. The separation of three powers divided by executive power, legislative power and judicial power is a common system of separation of powers. Among them, the degree of separation of executive power and legislative power varies in different political systems. For example, in the presidential system of the United States, the executive power and the legislative power are completely divided. The voters elect the president and the Congress respectively. In a system of separation of powers, the executive power implements policies and manages the daily operations of the government; the Legislative Council supervises the executive power and regulates it through legislation and financial approval; the judicial power plays an arbitration role, such as deciding whether the executive authority has Illegal laws and whether bills passed by Parliament are unconstitutional. Such a design comes from the French Enlightenment thinker Montesquieu, who believes that through the mutual restraint of power and the avoidance of any party's arbitrary actions, it will bring disaster to the people.

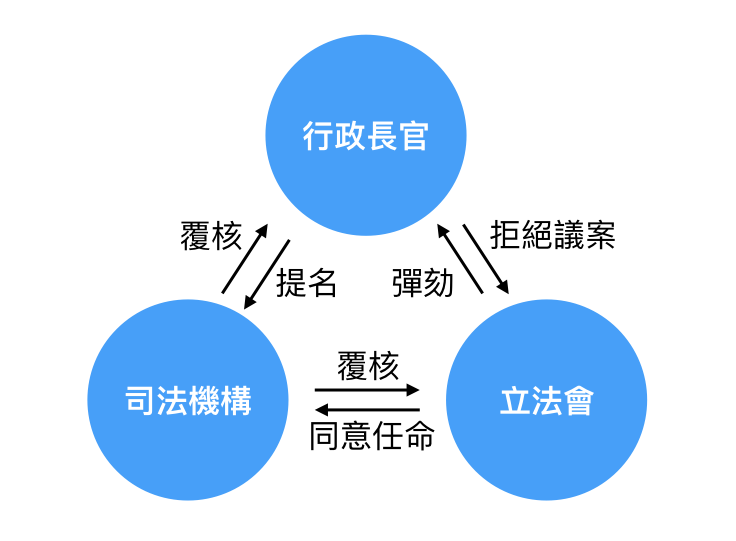

The design of Hong Kong's political system is similar to the presidential system of the United States. It is also divided into executive power, legislative power and judicial power. The Chief Executive and the Legislative Council are elected separately. The Chief Executive leads the executive body, that is, the SAR government. The Basic Law stipulates that the Chief Executive and the executive organs are under the supervision of the Legislative Council and the Judiciary, and the Legislative Council itself is also under the supervision of the Judiciary. The appointment or removal of judges of the Court of Final Appeal and the Chief Justice of the High Court in the judiciary also requires the consent of the Chief Executive and the Legislative Council.

Although the word "separation of powers" does not appear in the provisions of the Basic Law, the separation of powers can be seen everywhere. The functions and powers of the Chief Executive and the Legislative Council mentioned in Articles 48, 49, 50, 52 and 76 of the Basic Law can be seen to be mutually restricted. Bills proposed by the government must be submitted to the Legislative Council for deliberation and approval, and bills passed by the Legislative Council must be signed by the Chief Executive before they become law. If the Chief Executive refuses to sign a bill passed by the Legislative Council, he can send the bill back for reconsideration within three months; but if the bill is passed by a majority of not less than two-thirds of all members of the Legislative Council, the Chief Executive can only choose Sign or dissolve the Legislative Council. However, if the bill is still passed by a majority of not less than two-thirds of all members of the Legislative Council after the re-election, the Chief Executive must resign. The above-mentioned situation has not occurred since the establishment of the SAR, and the possibility of it actually happening is very low, but the existence of these provisions is enough to show that the Basic Law recognizes that powers should be mutually restrained.

In political practice, since the establishment of the SAR, there have been many cases where major motions have not been passed by the Legislative Council. For example, the political reform proposals in 2005 and 2015 were rejected. Cases where citizens try to overturn decisions of the government or the Legislative Council through judicial review are rare. As for the statement that "the chief executive has a detached status", it is easy for people to think that it means that the chief executive is completely unchecked, which does not comply with the stipulation in Article 25 of the Basic Law that "Hong Kong residents are all equal before the law". After resigning from office, Chief Tsang Yam-kuen was also sentenced to prison for violating "misconduct in public office" during his term of office. All these cases give Hong Kong citizens reason to believe that there is a certain degree of separation of powers in Hong Kong.

Having said that, the separation of powers in Hong Kong has many obvious flaws.

First of all, compared with other political systems with the separation of powers, the Basic Law gives the executive power significantly more power than the legislative power, so Hong Kong's political system is often referred to as "executive-led". For example, in the United States, the power to draft and approve the budget rests with Congress, and the president can only refuse to sign it for reconsideration; in Hong Kong, on the contrary, the power to draft the budget rests with the government, and the Legislative Council can only choose Pass or reject. Therefore, the ability of Hong Kong legislators to use the budget to change government policies is far lower than that of US congressmen. In addition, Article 74 of the Basic Law stipulates that when the Legislative Council proposes a bill, it must not "involve public expenditure or the political system or government operations", and "anything that involves government policy must obtain the written consent of the Chief Executive before it is proposed." . This alone determines that the power of policy setting is entirely inclined towards the executive power. Legislators want to propose some policies that the government did not intend to propose, not even the door.

Second, Hong Kong is not an independent polity. The Basic Law reserves many powers for the central government to intervene in Hong Kong's politics:

- According to Article 17 of the Basic Law, if the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress considers that a law passed by the Legislative Council "does not conform to the provisions of this Law concerning matters managed by the central government and the relationship between the central government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region", the relevant law may be returned. The law ceases to be effective in Hong Kong.

- According to Article 45 of the Basic Law, the Chief Executive is elected or negotiated in Hong Kong and then appointed by the Central People's Government. The general understanding is that the Central Government has the right not to appoint.

- According to Article 79, Paragraph 9 of the Basic Law, although the Legislative Council has the power to impeach the Chief Executive, even if the motion is passed by the Legislative Council with a two-thirds majority of all members, it must still be reported to the Central People's Government for decision, that is, the Central Government Power to overturn impeachment passed by the Legislative Council.

- According to Article 158 of the Basic Law, the right to interpret the Basic Law belongs to the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. Since the establishment of the SAR, the understanding of this provision has become that the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress can interpret the Basic Law at any time, and the judiciary in Hong Kong will implement this interpretation.

It can be seen that Hong Kong politics is not just a mutual check between the three powers. The central government can significantly or even completely cut some executive, legislative or judicial powers if necessary. Among them, the appointment and impeachment of the Chief Executive should be decided by the Central Government, which is exactly the basis for the so-called "Chief Executive's detachment", which means that the status of the Chief Executive is not completely restricted by the Legislative Council and the judiciary in Hong Kong, and the normal three powers Separate regimes are different.

Finally, from a practical point of view, the power restraint assumes a decentralized source of power, which is obviously flawed in Hong Kong. Since the establishment of the SAR, due to the limitations of the political system and practical operation, regardless of the mainstream public opinion in Hong Kong, the political stance of both the Chief Executive and the majority of the Legislative Council has been pro-Beijing. Since both the executive and the legislature are in the same camp and there is no fear of stepping down, effective mutual checks cannot take place. And for the judiciary, even if they try to remain independent, they must act within the existing political and legal system. If the system itself is flawed, there are very few things the judiciary can do. Under the above-mentioned difficulties, the separation of powers in Hong Kong can easily become tangible and intangible.

Further reading:

Gittings D (2016) System of Government, Introduction to the Hong Kong Basic Law (2nd Edition) . Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Lo PY (2014) The Background of Concepts, The Judicial Construction of Hong Kong's Basic Law: Courts, Politics and Society after 1997 . Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…