IYP 不是过眼云烟的新闻网站,我们提供实战能力,这里是值得您反复回看的档案室:iyouport.org

Year-end gift: Draw the future on white paper (Episode 5) - Smash the closed loop

Whatever the immediate outcome of the demonstrations, ordinary people in China are being radicalized by the experience, and many have organized themselves. This greatly raises the consciousness of the masses and the experience of fighting for justice will stay with them no matter the outcome. This bodes well for the future.

… Indeed, our popular solidarity across national borders is the best way to reduce tensions [of great power competition] and build a common international struggle for justice, equality and democracy, all of which are threatened by rulers around the world.

—— internationalviewpoint

欢迎回来!这里是第5集。

If you missed it, you can see it below:

- " Year-End Rites: Drawing the Future on White Paper (Episode 1) - Are we "Iranian"? 》

- " Year-End Ceremony: Drawing the Future on White Paper (Episode 2) - The torch has been lit, what next? 》

- " Year-End Ceremony: Draw the Future on White Paper (Episode 3) - Compete for IQ with the rulers, not with the public "

- " Year-End Rites: Drawing the Future on a Blank Paper (Episode 4) — Yes, there is an uprising that is hard to suppress "

[The following post was published on June 9th ]

"Policy Zero" is an exhibition of the modern state's capacity to oppress and the violence of its domination -

Shanghai has lifted its blockade. Over the course of two months, residents were locked in their apartments, with many reports of food shortages, COVID-positive young children being forcibly separated from their parents, and blatant authoritarianism that many young Chinese were experiencing for the first time.

It is doubtful whether the Chinese government could have anticipated how these younger generations might be inclined to react. The Wall Street Journal said the tough restrictions have "prompted young people to rethink their life plans," recounting stories of young adults in China who decided not to have children, gave up on their career plans, moved back in with their parents and gave up on finding love. According to the report, "accelerate (rot)" has joined the ranks of "lie down" and become the mantra of young people in their twenties and thirties. In a video banned by censorship, when a young Chinese man was threatened by authorities with generational consequences, he simply shrugged and said: We are the last generation.

These lockdowns are one thing, not two, from China’s mass surveillance, and they are both a wake-up call about the modern “state ’s” capacity to oppress and rule over violence.

Because without monitoring, this kind of violent blockade would not have happened. The Shanghai-style lockdown relied in part on brute force: neighborhood walls, home quarantines and police in hazmat suits snatching people off the streets.

But it relies above all on intelligence: where people went, who they met, what they said. Intelligence comes from long-term intrusive mass surveillance . The Chinese government has invested heavily in surveillance cameras and thermal imaging technology (for body temperature and other purposes) during the pandemic, expanding an already widespread spy network surveillance regime.

Shanghai’s COVID lockdown, while seemingly temporary, is unsurprisingly strikingly similar to Xinjiang’s social controls. As we have reminded many times - Xinjiang is just a testing ground for large-scale surveillance facilities, and the madness in Xinjiang will be a publicity stunt for these surveillance technologies, used to promote these violent methods of rule across the country and even the world.

Mass surveillance is inherently targeted at its own citizens, but expansion is a natural mode of protection for any state apparatus. Without solid legal limits, this is how things go: a "safety measure" quickly turns into social control; a fundamental right turns into a means of regulation. When there is a pandemic, all nightmares come together .

Don't let your thinking be limited to particularities such as ethnicity/race, region, class, gender, etc. Domination violence is always committed to targeting everyone, and may manifest in different forms, but there are no exceptions. The ruling class has been desperately trying to narrow your understanding of the disaster in order to protect the stability of its system - this one is only for Muslims , that one is only for "migrants ", that one is just a special phenomenon in Xuzhou ... No, not at all. No.

Domination violence is always a war against "people". They don't care about viruses, just like they don't care about so-called terrorism . What they pursue is total control. As you begin to reflect on Policy Zero, remember its roots; only if more people are aware of the roots can we hope to achieve strategically aligned, real solutions.

#China #ZeroCovidPolicy

Q: After Operation White Paper, I even saw some purge faction condemning the rebels. That was enough for me to feel what you mean by the superficial anger towards the media. The blank slate is not a matter of simply being cleared, but too many people are reducing their resistance actions to the level of the epidemic... What kind of direct action do you mean? Is it more effective than protesting? … China’s zero-clearance policy is unique, so how to analyze China’s white paper operation in a global context? …

iyp : Direct action is simply about cutting out the middleman and solving problems yourself rather than petitioning the authorities or relying on outside agencies. That is, don’t be represented. Many Chinese friends are familiar with the classic popular satire "wearing three watches," which assumes that many people are wary of government agencies.

For example, in the popular video, this 95-year-old Shanghai woman resisted Fangcang and fought against Dabai while waving a broom. It's just basic direct action. Although like all actions, winning requires strategy. Just a broom is not enough.

There have been many noteworthy direct actions in Chinese society. Although they were small in scale and may not have been fully interpreted, they were definitely not "just petitions" as described on the Internet; the white paper resistance was not entirely about epidemic prevention policies. Controversial, it's about fighting against oppression and restriction. That is, counter-domination. Although epidemic prevention policies are a starting point, they are not the starting point.

The water horses and iron fences deployed in cities under the zero-clearance policy only visualized the “domestic borders” that had always been relatively invisible.

Pandemic or not, China maintains a greater ability than any other country in the world to control the movement of its population within the country—through its infamous household registration policy, which links the provision of social services to regions. While Deng Xiaoping promoted a national labor market that allowed citizens a modicum of narrow market freedoms to seek employment across the country, social citizenship rights, including the right to state-subsidized health care, education, pensions, and housing, It's all done at the city level.

In recent years, the central government has promoted a technocratic biopolitics aimed at “distributing” populations with just the right quality and quantity within complex socio-spatial hierarchies of cities and regions, accelerating the deepening of the nightmare described above. This kind of "just-in-time urbanization" is the fantasy of pulling elite talents into elite cities and pushing the so-called "low-end population" to low-end places.

Although human mobility can never be controlled with such precision, the actual impact for labor migrants within China is the separation of living space and work space. Nearly 300 million people have moved to cities in search of work but are denied access to life-sustaining infrastructure such as housing and health services.

In other words, although capital and labor can move freely within China, there are still a large number of internal borders that restrict social reproduction.

These invisible boundaries sometimes manifest themselves physically. Despite a ban on deporting non-locals from the city following the police murder of refugee Sun Zhigang in 2003, cities still take coercive measures to deport people deemed "unsuitable." This includes bulldozing informal schools for refugee children and even razing entire refugee communities.

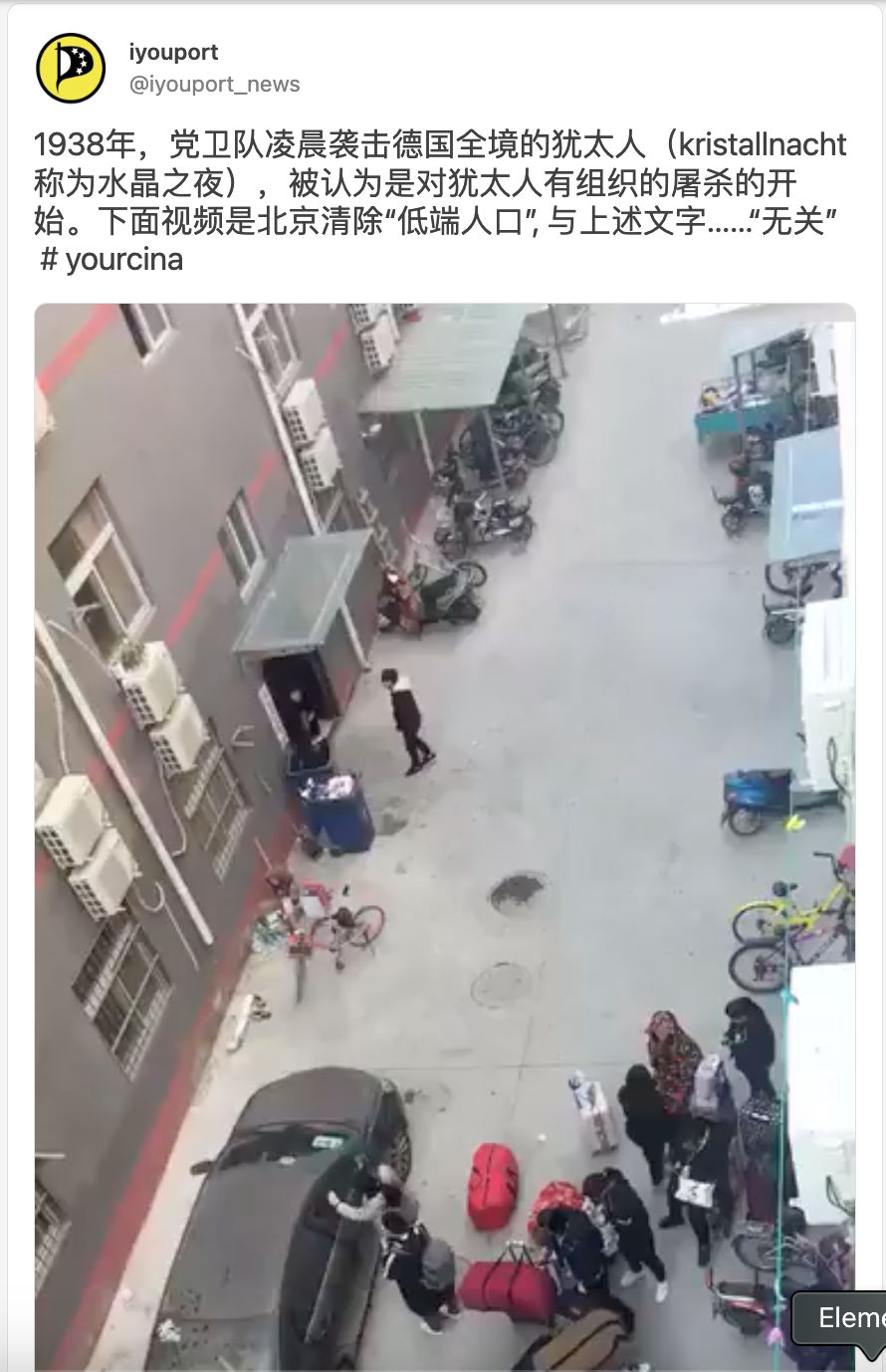

The most high-profile recent example of forced evictions of migrant workers came in 2017, when the Beijing government used a tragic fire as an excuse to carry out large-scale evictions and rebuilding of working-class neighborhoods, killing as many as 1,000 people in the process. 100,000 people have been displaced. It is called the Chinese version of Kristallnacht.

This coercive intervention arises from the disharmony between the national labor market and regional social welfare organizations, a dynamic that has been motivating sporadic social resistance.

There has been direct action throughout this long struggle. For example, in the 1990s, a small group of parents pooled their limited resources to open informal schools to provide low-cost education for children who could not enter the public system. Some of these mutual aid initiatives continue to develop among city agencies. While these efforts have not reversed the trend of educational and economic inequality in China, they have at least enabled millions of migrant workers to live in the same cities as their children.

The repression never stopped. In Beijing, at least 76 schools for refugee children were demolished between 2010 and 2018. School demolitions often trigger confrontational collective actions, including petitions to government officials, road blockades in demonstrations, and even more radical actions such as self-immolation. These struggles are often successful, defeating demolition plans and winning public school admissions for children, even as exclusivity continues in China's wealthy megacities.

The fall of 2017 marked a landmark moment when refugee communities (the so-called “low-end population”) fought against informal housing demolitions in Beijing. The rebellion not only aroused widespread sympathy among the city's citizens but also generated substantial cross-class solidarity. Beijingers from all walks of life organized through mutual aid networks to provide temporary housing, clothing and food to tens of thousands of displaced people. Prominent academics signed an open letter condemning the demolition. In a context where academic freedom has been drastically reduced under Xi Jinping, the stakes and symbolism of the letter are high. Some companies that rely on migrant workers are rushing to organize temporary housing, which is important if not altruistic. A broad coalition formed almost overnight to resist a city-state equipped with biopolitical machinery to reorganize life as the people saw fit.

Over the next few years, refugees' struggles to bring work and life closer together began to escalate.

The start of the lockdown on Wuhan has revealed much about the country's population management system. The success of the lockdown as an "anti-epidemic" measure cannot be attributed to an omnipotent centralized state . On the contrary, it was the state's incompetence and irrationality that allowed the virus to spread in the first place. Instead, dense mutual aid networks came into play early in the outbreak, facilitating the movement of essential supplies throughout cities and regions, allowing most people to stay home. Although the country ultimately committed to eliminating the virus, the key to success in Wuhan was the combination of the country's coordination capabilities and bottom-up initiatives.

At the most general level, the pandemic has widened mobility gaps between capital and goods, labor and people. While global migration and international travel have significantly declined due to the pandemic, global trade hit a new record of $28.5 trillion in 2021. In 2021, trade between China and the United States increased by 25%, and the global trade surplus reached a record high of $676.6 billion. At the same time, China has imposed aggressive new controls on the movement of people internationally and domestically.

A key difference between Wuhan and Shanghai is that during the latest lockdown, the state insisted on keeping people working. Trying to keep capital flowing while essentially shedding labor is challenging, but Shanghai authorities are willing to try. Their approach is that of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics , where the strategy is to make facilities as close to airtight as possible, allowing only essential items such as food and medicine to enter while preventing almost everyone from leaving the containment zone. This strategy, known as closed loop, allows capital to circulate while reducing human mobility to an absolute minimum.

When Shanghai's lockdown began later that spring, it became clear that the logic of closed loops had seeped out of the Olympic Village and into the broader polity. On April 11, the Shanghai government released a "whitelist" of 666 companies that could reopen amid the wider lockdown (a further 342 companies were added in May). These include the Tesla Gigafactory and Quanta, one of Apple's most important assemblers . So-called closed-loop management requires workers to enter the factory and stay there—eating, sleeping and working only within the confines of the factory. When workers are brought into a closed loop, they have no way of knowing when they will be allowed to leave.

Meanwhile, the work-from-home system endured by white-collar workers is essentially a closed loop organized at the household level . Starting in March, different communities experienced varying degrees of lockdown, with people barricaded in apartments in the most extreme cases. Food comes in through government channels, so-called "group buying" or online delivery services. Leaving home-based closed loops is strictly controlled and requires official permission. Some proactive officials also built literal walls in front of apartment exits to block residents' movement. City residents, many of whom are wealthy, face food shortages and anxiety as they are told to continue working, caring for children and other forms of labor while living under virtual house arrest.

Living at work and working at home superimpose spaces of production and social reproduction, with deleterious effects. Even many of Shanghai's poor and working-class residents don't fit into this closed loop. They live mainly in informal housing and work informally. Many people live in "group rentals," often exceeding the legal number of residents, as a way of obtaining shelter in Shanghai's expensive real estate market. Others live in self-built houses without legal status. These people, who live outside national jurisdiction, often did not receive adequate food distribution during the lockdown, leaving them to buy their own food and face price gouging. The challenge of buying food at market prices is compounded by the fact that these people’s occupations – construction workers, cooks and waiters, domestic workers and sex workers – often mean they have little income during lockdown. Most of these workers are also migrants from rural areas to the city, who have been prevented from leaving Shanghai to return to their hometowns during the lockdown. As a result, the survival crisis of the vast number of people at the bottom of this big city is imminent.

The people understand that these measures are no longer for the public good, even as they are required to continue working for capital in a closed loop at home, in the office or in the factory.

The heroic resistance of Shanghainese began in May, breaking out at Quanta Computer Company, an Apple supplier. People barricaded in their apartments shouted and sang from their balconies to comfort each other and promote emotional solidarity. " Voice of April", a video reflecting the tragic situation of people under lockdown, has exceeded 400 million views . Countless people continued to repost and copy it, breaking through China's powerful censorship blockade. Once again, anger unites people.

Resistance and direct action also occur outside so-called "closed loops," such as the food riots in Shanghai's suburbs, as many migrant workers living in informal housing have been without income or government supplies for weeks. In at least one case, people looted a vegetable cart and threw the contents haphazardly to the assembled crowd.

The media’s Overton Window focuses all the focus on the controversy over anti-epidemic policies, while ignoring the overall context of the struggle—thus helping to weaken the impact of the resistance on the system.

On the surface these struggles appear to be about lockdown, but they are closely linked to the violence of rule that marginalized displaced people for many years before the pandemic. Before COVID-19, rural migrants came to cities seeking wage labor as a means of survival because the countryside could no longer meet their needs. But given China's household registration system, efforts to move social reproduction to cities face constant obstacles and expulsions. As a result, refugee communities have been trying to build their own little world, including schools and housing, relatively close to their workplaces. The Shanghai blockade represents a spatial reversal while expressing the same political logic. The so-called closed loop does not cut off the space of work and life, but superimposes the two, so that all reproduction processes should occur in the workplace. The relative proximity of work and life means that the two should not be within the same boundaries. The closed loop cuts workers off from any meaningful social life, reducing them to naked labor. But workers resisted this effort to exert authoritarian control over body movement. People don't live just as labor for their bosses.

After that comes Zhengzhou. The Henan provincial capital is home to the world's largest iPhone assembly plant, with more than 200,000 workers at the Foxconn-owned factory. This factory is extremely important to the regional economy, and its products account for an astonishing 60% of the province's exports. After outbreaks broke out in the city and at the factory itself, Foxconn implemented closed-loop management, with workers prohibited from leaving the factory. As in Shanghai, the government and employers cannot allow problems at key nodes in the production network of the world's most valuable company, even as the entire city moves toward lockdown.

News emerged that on-site quarantine was being managed so poorly that sick people were said to be receiving inadequate care and not even enough food to eat. Anxious and angry, like Shanghai Quanta in the spring, the workers rushed toward the blocked exits. Hundreds, if not thousands, of workers jumped over the wall and fled toward their hometowns. Amid the regional lockdown, with no buses or other transportation options, Foxconn escapees had to trek long distances along roads and fields. The mass defections forced Foxconn to relent and allow workers to leave, in some cases with bus transportation arranged by local officials in the workers' hometowns.

This once again highlights the dystopian impulse of workers to resist shutting down human activity amid the accelerating circulation of capital. Although widespread poverty may await them when they return to the countryside, these escapees at least guarantee their own dignity and bodily autonomy.

China's system of population management was unique, both in the strength of the household registration system and in the fact that much of the conquered population was composed of state citizens of the dominant ethnic group. As we have emphasized , the Chinese state used more racialized colonial environments such as Xinjiang and Tibet as testing grounds to hone many of its social control practices—and these repressive tactics, mass surveillance technologies, and biopolitical control strategies are increasingly being used in Deployed in mainland metropolitan areas. Even in all cases, however, we see irresistible demands for the right to physical movement, to build lasting communities and fundamental processes of social reproduction, and to exist as not just a worker or consumer, but as a citizen Require.

The Chinese's strenuous struggle to make life and work relatively smooth should be seen in the context of the broader global resistance to capitalist border systems . A growing number of activists and scholars have shown how borders serve as a technology of spatial control that upholds racialized systems of exploitation and oppression. Controlling the movement of certain people is to maintain global relations of dominance. The United States and the European Union export mobility controls by delegating border patrols to countries in the Global South, while also internalizing borders through various forms of policing, surveillance, incarceration , and formal guest worker programs . At its best, growing demands for the abolition of borders are based on the belief that human beings should be able to move freely and have political and social rights that enable them to thrive in whatever space they may occupy. The aspirations and struggles of Chinese rebels are closely linked to the struggles of migrant workers and disenfranchised people around the world to demand the abolition of borders and escape the closed loops of capital.

Q: Peng Lifa of Sitongqiao is also appealing for votes, but you always talk about "direct action". Are you saying that Peng is wrong? Can direct action really be more effective than votes?

iyp : When it comes to political issues, when it comes to having a say in how things unfold, voting is the only strategy one can think of - to express one's opinion through voting, and to influence the votes of others. Mr. Peng is not wrong, most people will think so. Ballots give people a sense of being "involved in the political process" and seem to have an impact on the situation.

In fact, voting for someone else to represent your interests is the least efficient and least effective way to use political power. Broadly speaking, another approach is to take direct action and represent your own interests yourself.

Direct action is sometimes misunderstood as another form of campaigning, i.e. exerting influence/pressure on officials through tactical lobbying by political activists, such as making officials aware that the costs will be huge if they do not do so; but "direct action" Action” really means direct democracy.

Concrete examples of direct action abound. When you start to set up your own organization to find and rescue trafficked women and children , instead of lining up to petition or complain to the police, and shouting at the top of your lungs, "Let the central government take control of it," that's direct action. Direct action occurs when a person creates and distributes leaflets addressing an issue that concerns him, rather than expecting the regime-controlled news media to report or publish his letter to the editor. When people download color-coded front-end animations that use disguises and dismantle water horses to "unblock" themselves, that's direct action. Or a group of people who are knowledgeable enough to organize and provide homeschooling for kids in their community instead of just ranting on social media about how stupid schooling is and then sending their own kids to school, all of that All are direct actions. That is, do it yourself, without any scruples. autonomy and mutual aid,

In many ways, direct action is a more effective means for people to have a say in society than voting. First, voting is a lottery—if a candidate is not elected, all the energy his voters put into supporting him is wasted because the power they hoped he would exercise for them is taken away by someone else. In contrast, with direct action, you yourself can be sure that your work will deliver some kind of result; and the resources you develop in the process, whether it's experience, connections and recognition in the community, or your organization's infrastructure, It cannot be taken away from you.

Voting consolidates power over society in the hands of a few politicians; through sheer force of habit, let alone other methods of enforcement, everyone else is left dependent. And through direct action you become familiar with your own resources, your own abilities and your own initiative, discovering what the full reality is and how much you can accomplish.

The vote forces everyone in the movement to try to agree on a platform; alliances squabble over what compromises to make, with each faction insisting they know the best way and others not cooperating with their plans. And messed everything up. A lot of energy is wasted in these arguments and accusations. In direct action, on the other hand, there is no need for a huge consensus: different groups can apply different methods depending on what they believe in and feel comfortable with, and the methods can still interact to form a mutually beneficial whole. There is no need for people involved in different direct actions to quarrel unless they are really pursuing completely conflicting goals (or years of voting habits have made them subconsciously quarrelsome with anyone who disagrees). Conflicts over voting tend to distract from the real issues at hand, as people get caught up in the drama of one party versus another, one candidate versus another, one agenda versus another. With direct action, on the other hand, the problem itself is raised, targeted, and often solved.

Voting is only possible when election time comes. And direct action can be carried out at any time people see fit. Voting only works to address any issue on a candidate's political agenda, whereas direct action can be applied to every aspect of your life, in every part of the world you live in.

Voting is extolled as “freedom” in action. That’s not freedom—freedom is deciding what a choice is in the first place, not choosing between Pepsi and Coca-Cola. Direct action is true freedom. You make plans, you create choices, anything is possible.

Ultimately, there is no reason why the strategies of voting and direct action cannot be applied simultaneously. One does not cancel out the effect of the other. The problem is that many people view voting as their primary way of exercising political and social power, so much so that everyone spends too much time and energy on deliberation and debate, while other opportunities for change are squandered. In the months leading up to each election, everyone debates voting, what candidate to vote for or whether to vote at all, and the voting itself takes less than an hour. It doesn't matter whether you vote or not, but remember there are other ways to make your voice heard.

What is needed is a movement that emphasizes more direct forms of action and the possibilities offered by community involvement. These need not be seen as contradictory to voting. We can devote one hour a year to voting and the other three hundred and sixty-four days and twenty-three hours to direct action.

Those who are completely disillusioned with representative democracy, those who dream of a world without presidents and politicians, can rest assured that if we all learn how to proactively use the power that each of us has, the question of which politician can be elected to office will become a meaningless question. They only have this power because we entrust it to them. The direct action movement puts power back where it belongs, in the hands of the people from whom it originated.

Q: Translations of the works of Gene Sharp, the godfather of non-violence, began to circulate on the Internet when the paper was first released. I don’t know how to describe it. If you know who the suppressor you are facing is, you should hurry up now. Wear a bulletproof vest and a helmet instead of reading about nonviolence. I am not saying that non-violence is useless, and I am definitely not a fan of violence. I know that violence alone may be difficult to solve the problem, but the current situation is that everyone involved in this debate is trying to drag the topic into the so-called From a moral perspective, all kinds of Tolstoyans, this is wrong no matter what. I don’t understand the theory, but I know that morality cannot determine victory or defeat in the process of fighting bandits. Half are Tolstoyans and the other half are Zhang Xianzhongists. Does anarchism advocate violence or nonviolence? Is the "strategic consideration" you mentioned a conclusion? How to convince Tuo and Zhang?

iyp : The state is fundamentally a form of violence - violence is the mother tongue of the state. Once the debate shifts to violence vs. non-violence, the ruling class is back on their home turf, where it is always they who can best justify themselves and carry out their actions, not you.

For actors, there are some principles you must understand before deploying tactics…

📱 Preview of the next episode’s topics:

Tolstoy or Zhang Xianzhong?

🏴️

——To be continued——

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…