Hello~ 沙丘研究所(Dunes Workshop)是一个独立的线上原创内容发布平台,内容有关于城市、建筑、文学、艺术以及留学生活,成员来自哈佛大学设计学院以及麻省理工大学设计学院。 同样,欢迎关注我们的微信公众号“沙丘研究所”,第一手的推送内容会发布在这里;以及 Instagram账号@dunes.workshop 第一手的图像/视频内容将会发布在这里。

The Dune Institute's Amateur Book List of the Year

Although there are many methods and mediums, books are still the fastest and most effective means of learning. The Dune Institute needs to be strongly involved in the production of Internet content and knowledge dissemination, but reading the original texts of thinkers and writers is still the most important way to improve itself.

As 2020 draws to a close, we've picked 7 of the most inspiring books to share with you. This recommendation method is "amateur" because we do not approach it through literary criticism or literary research, but through a very relaxed and everyday feeling. This list is not intended to summarize public events or major news in the intellectual/publishing world in 2020. The choice of the author does not matter whether the author is alive or not, domestic or foreign, or even Kafka and Dostoev in the seven books. Skye took two copies each. In general, it is very subjective.

Having said so many warnings, I still hope that everyone will enjoy this push, because the book is really good!

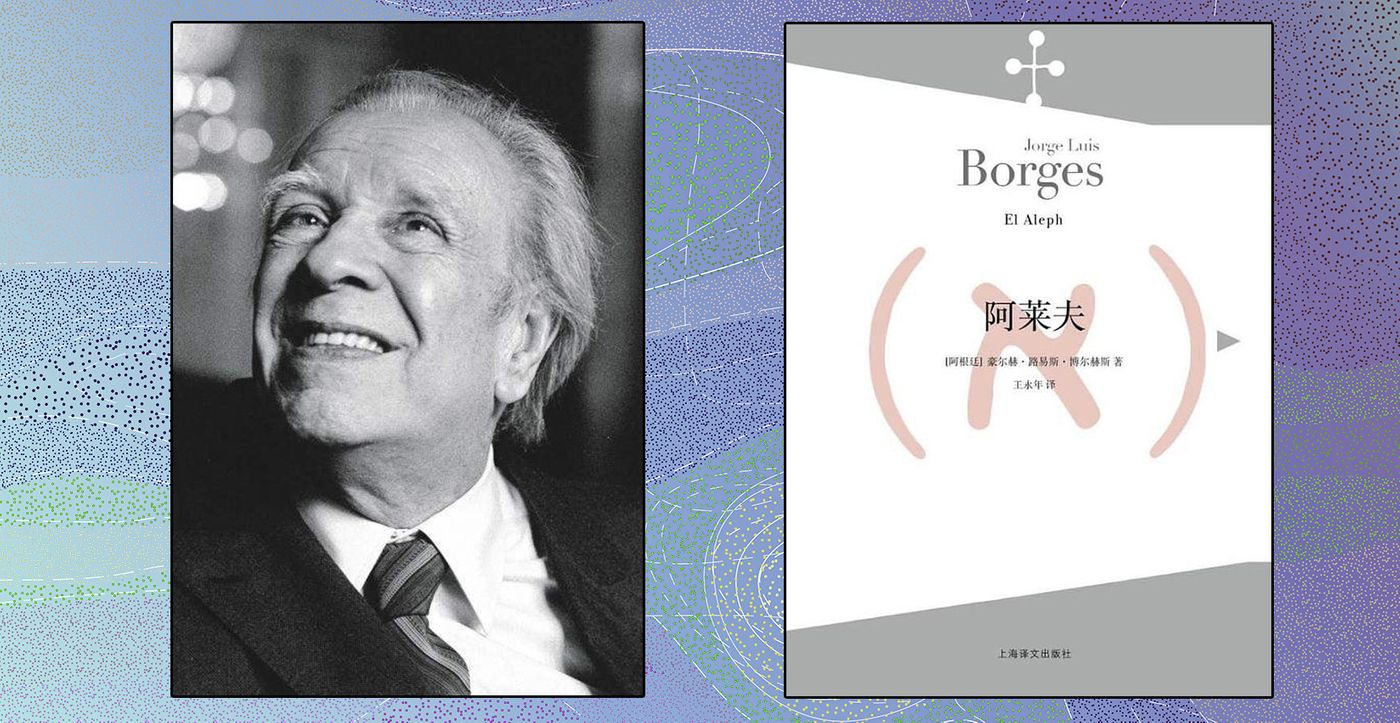

01 Borges, "Aleph"

(Recommender: Chen Feiyue)

The Dune Institute's name does not come from Frank Herbert's sci-fi "Dune", but is inspired by Borges' "The Book of Sand." In the creation of works, Borges is indeed a strong guiding force for us. Re-reading his short stories has always brought me solace in times of depression or self-doubt. To be honest, I often confuse the books "The Book of Sand", "Aleph", "The Garden of Forking Paths" and "The Collection of Fictions", and many times I can't remember the specific source of a short story that I suddenly want to revisit. which one of them. But this kind of confusion is probably appropriate.

I recommend "Aleph" over the other three, just because one of "Eternal Life" is included in this one. (Of course I know now because I just checked it.) After reading Borges continuously for a while, a few of them will slowly emerge like islands in the sea—maybe a sentence or two of them It may be a sense of game that is structurally worth playing and weighing, and it may be because a certain state of the story makes people imagine the state when Borges wrote it... For me, "Eternal Life" is definitely It is one of them, and many times this strong-smelling work tempts me to go through it again in my mind.

The first time I read this should have been at the beginning of the year, when I had a dinner date with a friend, I arrived early and read the e-book on my mobile phone. It was still cold, but I was just wandering outside. This article quickly became popular, because I was almost in a state of over-excitement because of the unsuspecting encounter with this kind of work. ——“It’s raining, it’s raining slowly and powerfully…” ——I remember reading a paragraph after reading a few pages, I had to finish reading a few pages, raise my head to take a breath, put my phone back in my pocket, and walk around to calm down Feel free to read on. In general, there seems to be a typical type in Borges' writings, in which he concocts a mysterious, infinite and repetitive microcosm . The piece "Eternal Life" must have been quite infectious to me. Of course, as far as I'm concerned, the same goes for The Ring of Ruins, The South, The Blue Tiger, The Babylonian Lottery, Emma Zonzi, and so on - after reading some of these images will gradually emerge and the previous to revisit. It's just that perhaps because of the special scene at that time, "Eternal Life" is particularly memorable to me. (Another friend of mine shared a similar experience. He was reading "Congress" on the plane going abroad. He read it for a while, then got up and read it for a while. Erges leads it to the door.)

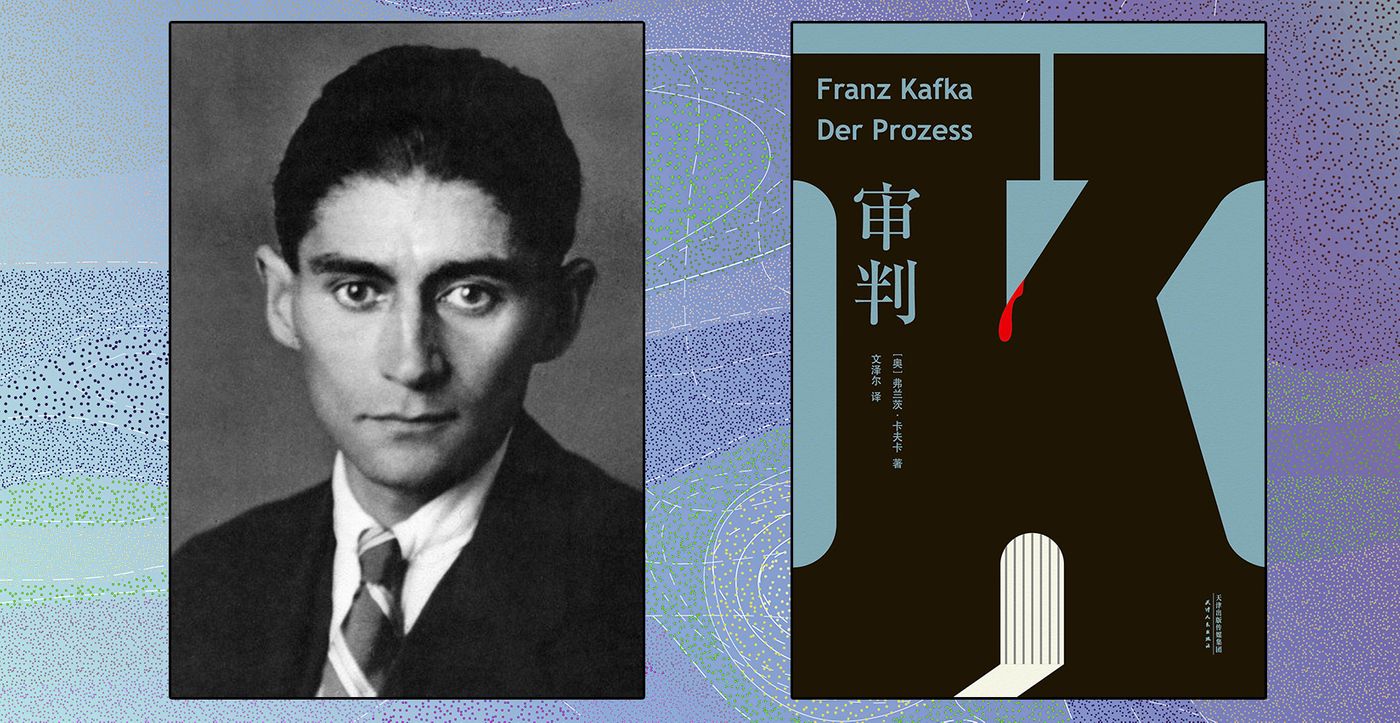

02 Kafka, The Trial

(Recommender: Li Yalun)

Reading Kafka's novels is one of the things I enjoy most this year. For me, the two novels, The Trial and The Castle, show the world and life at their most essential and true.

Neither novel may be a compelling story in the traditional sense, or even a plausible storyline or an evolving plot development in the traditional sense. In Kafka's stories, there is always a certain majestic and indifferent power that presents itself so clearly to the world, that one can never reach or enter it. All events unfold in this confrontational relationship, shrouded in a misty absurdity.

I think "The Trial" is actually a very arresting story: the protagonist "K" is arrested on his 30th birthday. There were no charges, no arrest procedures, and even freedoms were not affected. As I read this book, I could barely stop, I was gripped by this bewildering premise. Like the protagonist, I was so curious: why was he arrested? what court? What law was committed? How to punish? In order to find the answer, the protagonist enters an intricate and mysterious system, but a series of events does not push the story to an answer, but slowly reveals an inexplicable maze hidden in daily life .

The scenes, spaces and characters in this story have a wonderful illusion of abstraction of reality - a long, empty hallway, or a courtroom hidden in an apartment, and the narrow painter's bedroom at the end of the stairs leads to the oppressive courthouse . "Trial" seems to show a fragment of life, that is, "fate" befalls people absurdly, and we are so puzzled and reluctant to accept it, so we try to hide and try to find the reason. In the process, this running and hiding seems to have become the most important motivation in life.

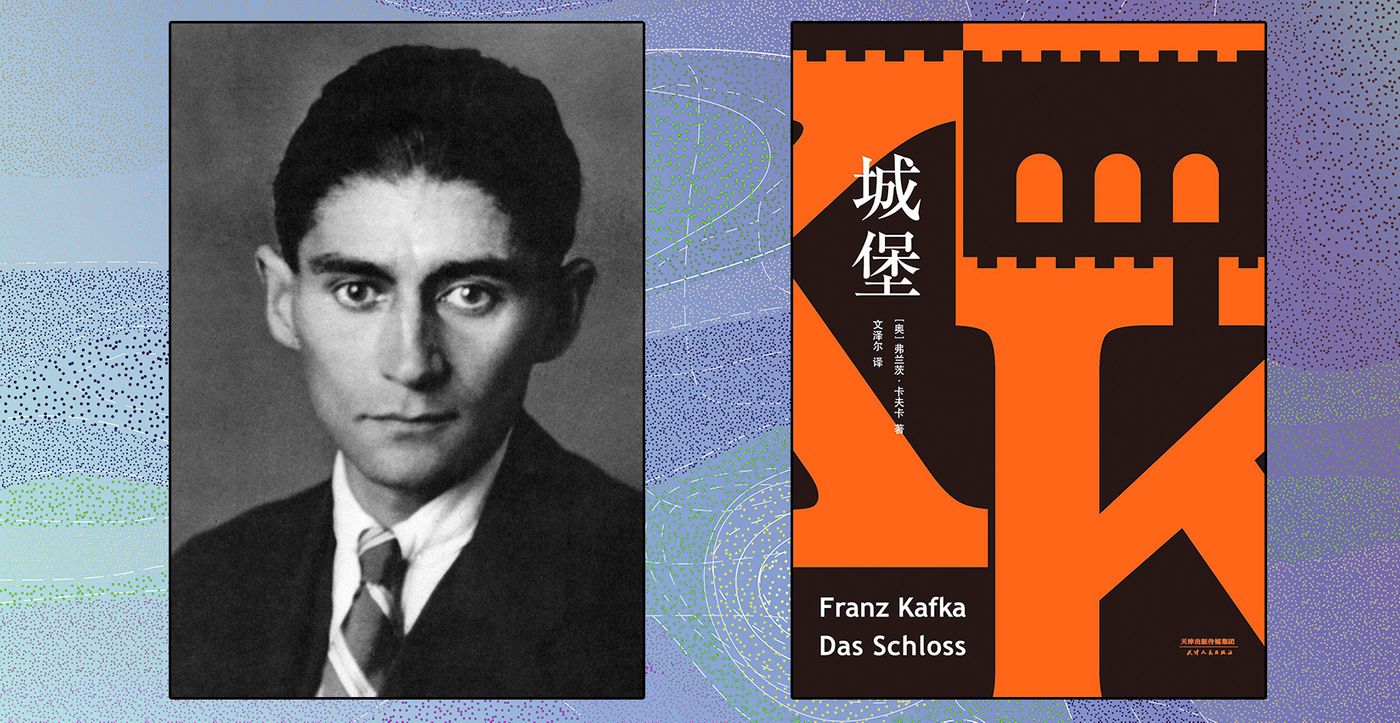

03 Kafka, The Castle

(Recommender: Li Yalun)

Both "The Castle" and "The Trial" have a "god"-like existence, and this invisible thing runs through and covers the lives of ordinary people. Whether it's a courtroom or a castle, it controls everything, but it's intricate and untouchable.

Although very similar, these two novels are two opposite stories, namely, the protagonist in "The Trial" is persecuted by a mysterious power and runs into hiding, while "The Castle" is about the protagonist in order to be accepted by the mysterious power. With futile efforts.

In comparison, the story of The Castle seems to be colder and more profound to me. In this story, the protagonist "K", who was appointed as a land surveyor, came to the city, and he kept trying to enter the castle in front of him and integrate into the life of this new city, but he kept finding that the city and this huge institution were so Confusing, elusive and elusive. If The Trial shows destiny at work, The Castle seems to me the process of life itself. We were all born like protagonists into a ridiculous world and a system that we may never understand and fit into, but we always forge ahead in such a cloudy environment , trying to achieve something beyond isolated life.

When I was still in middle school and high school, Camus' "The Outsider" deeply shocked me, it gave me a surprising realization that the world is cold and absurd, and people can embrace it. To this day, I am passionate about existential philosophy. "The Myth of Sisyphus" and "Fear and Tremor" are all my favorite works, but I think Kafka brought me a deeper resonance. Maybe my understanding of the story is not the author's original intention, but the nightmarish picture he painted also deeply moved me. A friend mentioned that he was surprised that Kafka was so well-known and popular, because his works may not be so easy to read or even difficult to understand. However, because of his fame, many critics interpret his work from various angles, such as a critique of the legal system or a denunciation of the bureaucracy. But I think Kafka is only depicting his own most real world, a world of absurd and mysterious majesty. Chen Feiyue and I also discussed that Kafka's writing is "not good" because there are almost no golden sentences full of "philosophy", but I hope that many people will be moved by his uniqueness and authenticity, and will resonate with him.

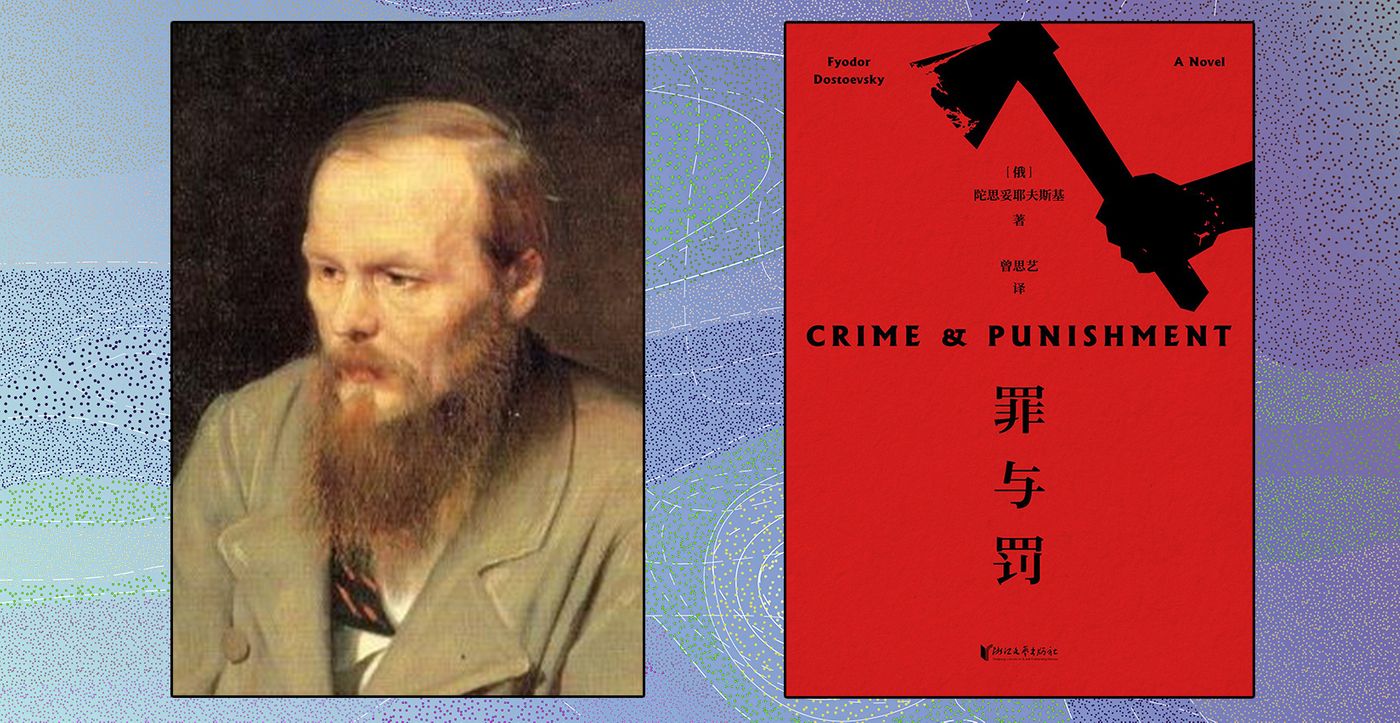

04 Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

(Recommender: Chen Feiyue)

The story of "Crime and Punishment" is very simple to summarize, but because the writer penetrates into the inner world of the protagonist, the book is very expansive in nature. The story carries very heavy and turbid thoughts, and it also constantly evokes the "darkness" in the readers' own hearts. During the peak of the epidemic, I seldom went out. I often stayed (trapped) in my room to read this book. After sitting for a long time, I got up and paced back and forth. This state seemed to match the protagonist Raskolnikov inexplicably.

In Crime and Punishment, you can feel the confluence of some of Dostoevsky's early short stories: the protagonist often talks to himself when he is alone, and his thoughts are full of pathological, delirium, and madness. Seeing lighter than dust, and often believing in a Nietzschean superhuman philosophy, placing himself at the top of the human pyramid. Here you can feel the shadow of the "basement man" as the prototype in "Notes from the Basement". And whenever Tuo writes about the river and bridge in Petersburg, I think of a similar space in White Night. In addition, after the death of the alcoholic Marmeladov, his sick wife's irrational running on the street reminds me of a similar scene in Tuo's earlier "Poor Man". As for the exile in Siberia at the end of the book, of course, you can refer to "Notes from the House of the Dead". It can be said that the book "Crime and Punishment" generally shows the topics and materials that Tuo was interested in in the early and middle stages. As for a later and more comprehensive collection, it is "The Brothers Karamazov".

When many people recommend Dostoevsky's works, they will emphasize his educational significance and enlightenment significance. I think this still seems to be at the level of discussing "what's the use of reading" a literary work. In addition, many people's recommendations may also emphasize what kind of problems "Crime and Punishment" can reflect in jurisprudence and psychology, but this is also a narrowing of literature, because a more overall "imitation" of the world has been into a "category" that can be explained. So let’s put it simply, as a creator, I have been deeply inspired by this work. For example, there is a secondary character in the novel named Svidrigailov who has a diabolical hunger for sex. (It can be said that he is also a mirror image of Raskolnikov.) This character is the most memorable to me, because both its setting and description are extremely well controlled, especially the paragraph before the suicide is written superbly.

When Borges wrote the preface to the Spanish edition of "The Demons", he opened: "The discovery of Dostoevsky, like the discovery of love and the discovery of the sea, is a memorable day in our lives. " I think it's fair.

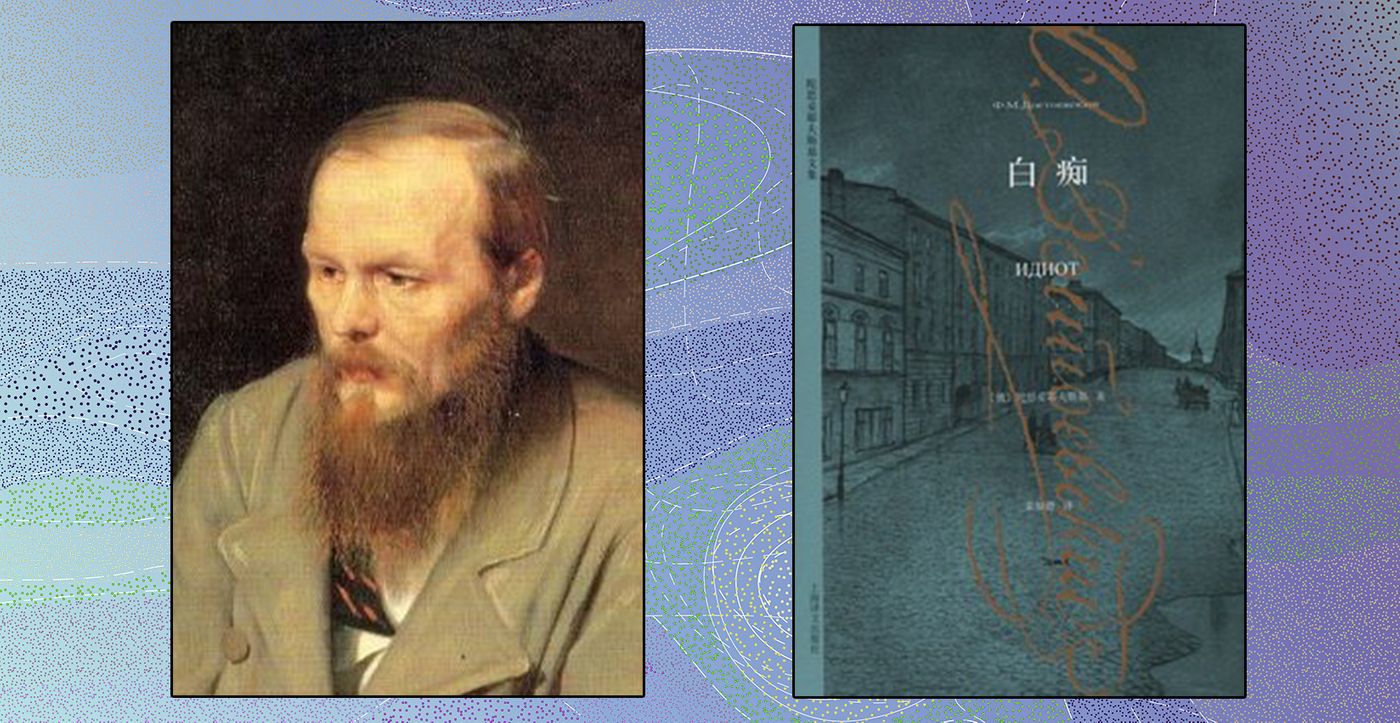

05 Dostoevsky, The Idiot

(Recommender: Chen Feiyue)

Fiction needs to create its own space. I wrote an article a while back that analyzed Crime and Punishment and The Idiot, trying to show Dostoevsky's unique approach to space and people. But obviously the treatment of space is only a small part of such a work, and even my overall impression of the book cannot be summarized.

Although Crime and Punishment is vast and complex, the whole can still fall on a single thread—the protagonist’s motives, murder, struggle, and confession. This main line is easy to identify, and readers with thicker lines can even skip or skim some of the branch lines that stick out from the center of the plot, and still be able to return to this clear story line later without getting lost. But Idiot is a little more challenging in this regard. Readers may first think that the triangular relationship between Duke Meshkin, Nastasya Filipovna and Luo Guoren is the basic story line, but later will find that this line becomes blurred, gradually hidden, and then jumps to another. above.

After a dizzy-prone midsection, the novel's ending rediscovers the track. Perhaps because I was relatively ignorant of the religious context, I didn't realize that the thread running through this novel was essentially the relationship between Christianity and people . Including the important romantic part in the story can also be said to reflect the irreconcilable relationship between a "neighbor's, carnal love" and a "Christian, saving love".

Interestingly, after I actually finished reading this book, I often re-read the middle section that was a little lost at first—one is the visit of the Duke of Meshkin to Luo Guoren’s house, and during the conversation between the two, the Duke of Meshkin mentioned. and "Four Stories" of Faith in Russian Land. One is the description of Hippolyte. These two places, together with Duke Meshkin's face that "there should be no hatred", have planted deep seeds in my heart, prompting me to reflect on the relationship between faith and nothingness, on the "abstract idea of love" and "the idea of love". love specific people" distinction.

06 Li Pen, "The Sheep Stuck"

(Recommender: Chen Feiyue)

In 2015, I first read "Out of Focus Horse" and felt like I had dug up a treasure. "Anyway, the horse is out of focus, and it can't find its own outline."

In 2020, I may be able to say that these hundreds of words metaphor and summarize a kind of "suspended" state of modern people and a certain quality of losing their spiritual hometown and identity. (But wouldn't say that either.) When I read it, I just thought the text was light-hearted and had an eerie and wondrous aura. It is not serious, nor does it aim at practical significance, but as a small fable-like story, it achieves a strong sense of picture and literary quality. At that time, there were a lot of very talented writers active on the Zhihu platform, such as Li Pen and Liang Bianyao, etc., and it seemed that they all had such characteristics.

There are many short stories such as "Out of Focus Horse" in the book "Sheep Dumb", all of which capture a small moment of drift or distraction in daily life. Many of these strange and accurate observation methods will make readers understand Heart smile. To a certain extent, the sharpness and lightness of Calvino's writing and The Sheep Bewildered, and Yukio Mishima's (for example, The Afternoon Drift)'s writing of the sublime representation of everyday life can all be related. Of course, this comparison is still a bit far off.

For friends who study architecture and cities, I strongly recommend "Urban Iconology" and "Rural Iconology". (The two are the longer of his writings.) Calvino mentioned in a March 1983 lecture at Columbia University's master's in writing: "From a friend who is an expert in urban planning, I listened to To say that this book [Invisible Cities] touches on a lot of their issues, and it's not a coincidence, because the context is the same."

If you can continue to tolerate me, I would like to say that these two articles by Li Pen also touch upon many issues in more academic language in architecture and urban studies. Of course, Mr. Li Pen still wrote these things down in a very Li Pen way - easy to feel but difficult to determine .

The turbulent 2020 has made everything pan-politicized, and frankly, my own way of thinking has been affected a lot. But I think this pan-politicization is unfortunate and alarming for writers, because it makes a lot of things taut, as if everyone is always ready for the next debate. In this case, we may still have courageous words, rational words, and insightful words, but less and less loose, humorous, or cunning words. "Sheep Dumb" belongs to the latter and is worthy of our cherishing.

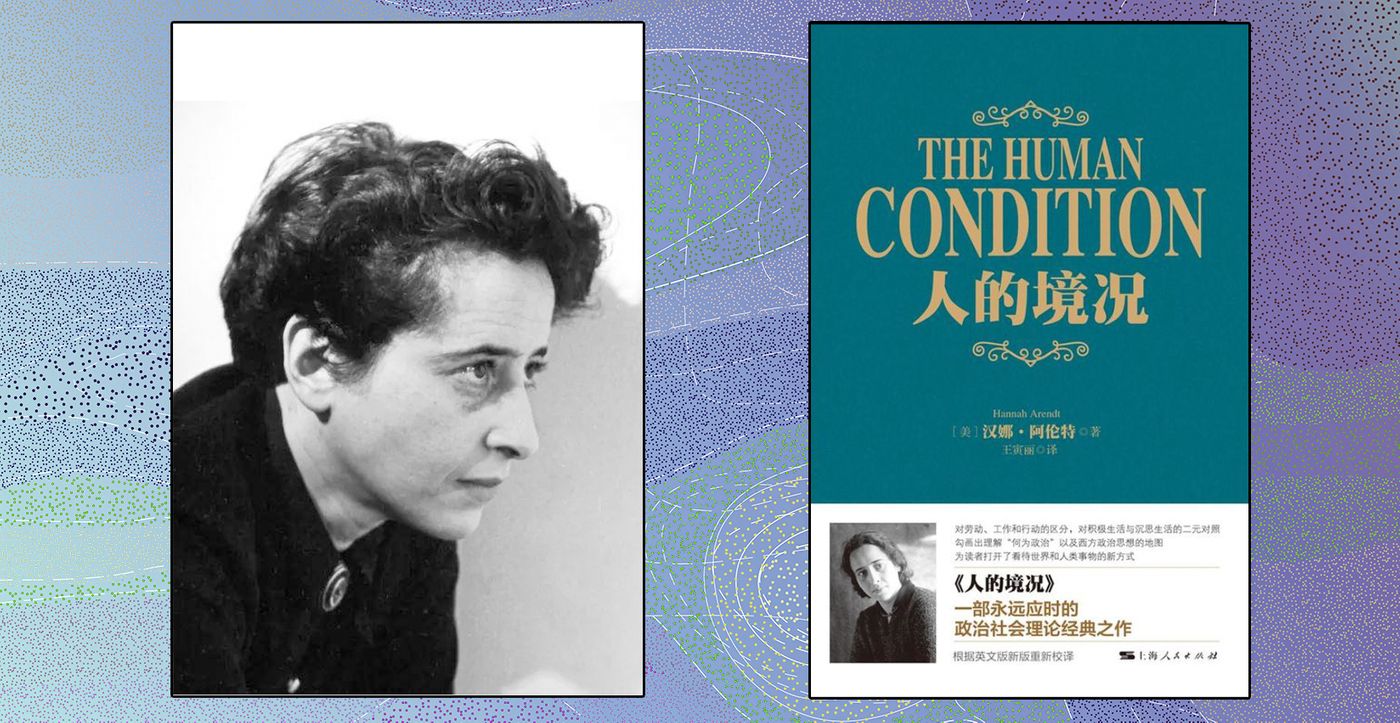

07 Arendt, The Human Condition

(Recommender: Chen Feiyue)

I became interested in political science and political philosophy because "public space" is always discussed in architectural urbanism. (Of course, the concepts of "public domain" and "public space" are not the same.) I agree with Li Yalun's sentiment: the more the word "public" is heard, the more confused it is. "public"? Aside from concepts and definitions, we lose our most intuitive sense of the word because of its high frequency.

Before you settle on a category and start throwing things into it, you need to figure out what the more fundamental thing is. For me, Arendt's The Human Condition does just that. I started reaching out to Habermas and Arendt over a year ago for schoolwork and other things, and I put a lot of their words into my projects as golden rules. I feel ashamed when I think about it now, because it is just citing for the sake of citing, and it is forcibly projecting the crystallization of other disciplines into the field of architecture.

Arendt stated clearly at the beginning of the book that she identified three fundamental human activities, "labor", "work" and "action". This triadic differentiation has very powerful explanatory power.

The Human Condition was written in the 1960s, a time when ideological movements were in full swing in countries around the world. In addition to this political realm, people have also experienced events such as astronauts landing on the moon, waves of automation sweeping production methods, and so on. In the foreword, Arendt writes: "What I'm going to do [in this book] is very simple, just think about what we're doing." She explains a general situation in the 1960s with a well-established frame of mind . In order to explore the state of this modern man, she mainly seeks answers from the ancient Greek period.

There are some buzzwords in 2020, such as "involution", "worker", "Versailles", and these concepts can still find their way of explanation in the book "The Human Condition". Combining Arendt's thoughts on key words such as "technology", "publicity", "speech", "automation", "labor society", we can have a more thorough understanding of the newly emerging words today.

Welcome to the discussion, and welcome to share your annual book list~

Welcome to the WeChat public account "Dune Research Institute". The first-hand content will be here.

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…