【推文】James Lindsay - "To fix climate anxiety, we first have to fix individualism." –LA Times

這是 James Lindsay 最近寫的推文,只有幾段字再加幾張圖再加文章原文及翻譯

文章本身就是「氣候正義」宣傳文,Intersectionality / (歧視的)交叉性內容像是順便提到的(也可能不加入一些這種內容不過癮)

連結

原推文 - x.com/conceptualjame...

Gettr版本 - gettr.com/post/p3bi0...

原文及個人翻譯

James Lindsay推文

Are you paying attention yet?

"To fix climate anxiety (and also climate change), we first have to fix individualism." –LA Times

To fix their mental illness about the climate, we have to let the mentally ill people control us. That's what that literally means.

你有注意到嗎?

「為了解決氣候焦慮(以及氣候變遷),我們首先必須解決個人主義。」 ——洛杉磯時報

為了解決他們對氣候的精神疾病,我們必須讓精神疾病患者控制我們,這就是字面意思。

被引用推文(整串)

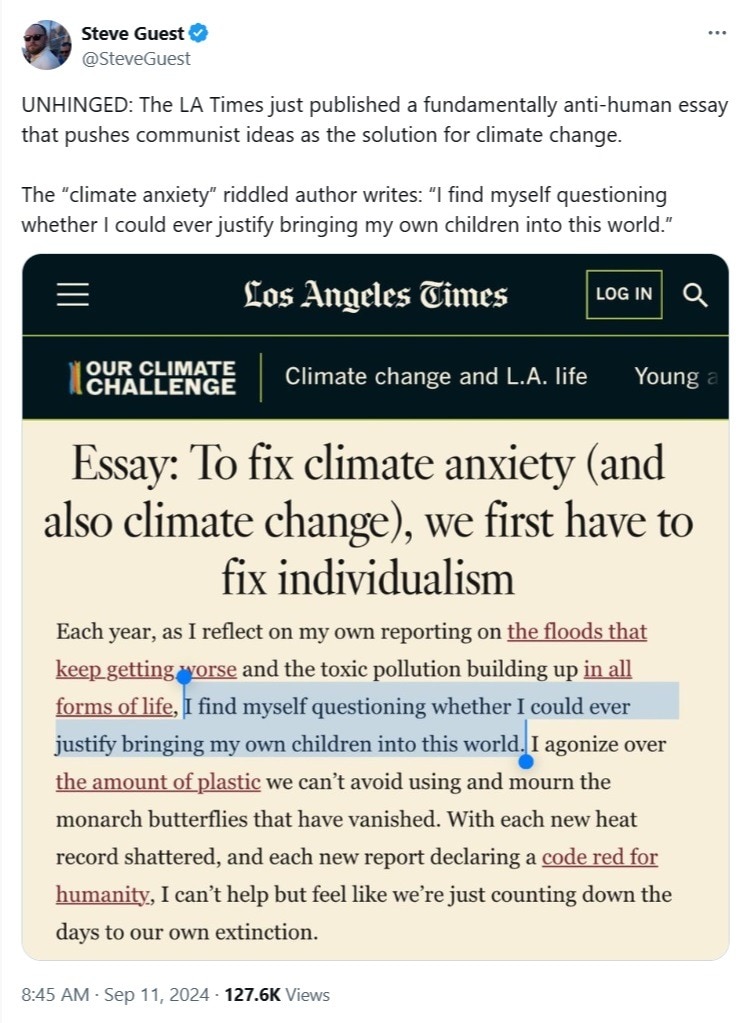

UNHINGED: The LA Times just published a fundamentally anti-human essay that pushes communist ideas as the solution for climate change.

The “climate anxiety” riddled author writes: “I find myself questioning whether I could ever justify bringing my own children into this world.”

精神錯亂:《洛杉磯時報》剛剛發表了一篇從根本上反人類的文章,推動共產主義思想作為氣候變遷的解決方案。

這位飽受「氣候焦慮」困擾的作家寫道:「我發現自己在質疑自己是否有理由將自己的孩子帶到這個世界上。」

Here is another unhinged aspect of that paragraph: “I can’t help but feel like we’re just counting down the days to our own extinction.”

https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2024-09-11/climate-anxiety-essay

這是段落的另一個精神錯亂的方面:“我情不自禁地覺得我們只是在倒數計時我們自己的滅絕。”

(後面只有截圖我還不如整篇抄過來翻譯)

LA Times文章

(以下機翻不作太多編輯,太長)

How do you cope? I feel the sorrow, the quiet plea for guidance every time someone asks me this question. As an environmental reporter dedicated to helping people make sense of climate change, I know I should have answers. But the truth is, it took me until now to face my own grief.

你如何應對?每當有人問我這個問題時,我都會感到悲傷和安靜的尋求指導。作為一名致力於幫助人們了解氣候變遷的環境記者,我知道我應該有答案。但事實是,我直到現在才面對自己的悲傷。

My heart keeps breaking whenever I meet yet another child struggling with asthma amid orange, smoke-filled skies. I, too, am reeling from the whiplash of extreme drought and extreme rain, and I’m still haunted by the thought of a mother having to call each of her daughters to say goodbye as the homes around her cave to fire.

每當我在橘色煙霧繚繞的天空中遇到另一個患有氣喘病的孩子時,我的心就碎了。我也正遭受極端乾旱和極端降雨的折磨,一想到當洞穴周圍的房屋著火時,一位母親必須打電話給她的每一個女兒來告別,這種想法仍然困擾著我。

Each year, as I reflect on my own reporting on the floods that keep getting worse and the toxic pollution building up in all forms of life, I find myself questioning whether I could ever justify bringing my own children into this world. I agonize over the amount of plastic we can’t avoid using and mourn the monarch butterflies that have vanished. With each new heat record shattered, and each new report declaring a code red for humanity, I can’t help but feel like we’re just counting down the days to our own extinction.

每年,當我反思自己對日益嚴重的洪水和各種生命形式中不斷累積的有毒污染的報道時,我發現自己在質疑自己是否有理由將自己的孩子帶到這個世界上。我對我們無法避免使用的塑膠數量感到痛苦,並對消失的帝王蝶表示哀悼。隨著每一個新的高溫記錄被打破,每一份新的報告都宣佈人類的紅色代碼,我不禁覺得我們只是在倒數計時我們自己的滅絕。

“Climate anxiety” is the term we now use to describe these feelings, but I must confess, I was perplexed when I first heard these words a few years ago. Anger, frustration, helplessness, exhaustion — these are the emotions I come across more often when getting to know the communities bracing for, or recovering from, the devastation of what they’ve long considered home.

「氣候焦慮」是我們現在用來描述這些感受的術語,但我必須承認,幾年前我第一次聽到這些話時我很困惑。憤怒、沮喪、無助、疲憊——這些是我在了解那些正在為他們長期以來視為家園的家園遭受破壞而準備或恢復的社區時經常遇到的情緒。

Then a college student asked me about climate anxiety. It came up again on social media, and again in personal essays and polls. This paralyzing dread was suddenly the talk of the town — but it has also, very noticeably, remained absent in some circles.

然後一位大學生問我有關氣候焦慮的問題。它再次出現在社交媒體上,並再次出現在個人文章和民意調查中。這種令人癱瘓的恐懼突然成為全城的話題——但值得注意的是,它在某些圈子裡仍然缺席。

All this has led me to wonder: What, exactly, is climate anxiety? And how should we cope? At first blush, this anxiety seems rooted in a fear that we’ll never go back to normal, that the future we were once promised is now gone. But who this “normal” is even for (and what we’re actually afraid of losing) speaks to a much more complicated question:

這一切讓我想知道:氣候焦慮到底是什麼?而我們又該如何應對呢?乍一看,這種焦慮似乎源於一種恐懼,即我們永遠無法恢復正常,我們曾經承諾的未來現在已經消失了。但這個「正常」到底是為誰而存在(以及我們實際上害怕失去什麼),這說明了一個更複雜的問題:

Is this anxiety pointing to a deeper responsibility that we all must face — and ultimately, is this anxiety something we can transcend?

這種焦慮是否指向我們所有人都必須面對的更深層的責任——最終,這種焦慮是我們可以超越的嗎?

For Jade Sasser, whose research on climate emotions has been grounded by her own experiences as a Black woman, these questions sharpened into focus during a research-methods seminar that she was teaching early last year at UC Riverside.

對於傑德·震蕩波來說,她對氣候情緒的研究是以她作為黑人女性的親身經歷為基礎的,這些問題在她去年年初在加州大學河濱分校教授的一個研究方法研討會上成為焦點。

The class — all female, many from low-income immigrant communities — had been a fairly quiet group all quarter, so Sasser was surprised when the room completely erupted after she broached what she thought would be an academic, somewhat dispassionate discussion about climate change and the future.

這個班級——全是女性,許多來自低收入移民社區——整個季度都是一個相當安靜的群體,所以當她提出了她認為是學術性的、有點冷靜的關於氣候變遷和氣候變遷的討論後,房間裡完全爆發了,震盪波感到很驚訝。

Every student was suddenly talking, even yelling, over one another. Thought after thought tumbled out as they shared that not only does the future feel bleak when it comes to the job market, the housing crisis and whether their generation will ever be able to “settle down with kids” — but all this is many times worse when you’re not white, not documented and not born into a college-educated family.

每個學生突然都開始互相交談,甚至大喊大叫。當他們分享意見時,他們的想法不斷湧現,不僅在就業市場、住房危機以及他們這一代是否能夠“與孩子安定下來”方面,未來感到黯淡,而且所有這一切都更糟糕當你不是白人、沒有證件、也沒有出生在受過大學教育的家庭時。

How can they feel hopeful about the future, they asked, when, on top of everything already stacked against them, they also have to worry about wildfires, extreme heat and air pollution getting out of control?

他們問道,除了已經對他們不利的一切之外,他們還必須擔心野火、酷熱和空氣污染失控,他們怎麼能對未來充滿希望?

“It was literally a collective meltdown unlike anything I had ever experienced,” said Sasser, whose podcast and book, “Climate Anxiety and the Kid Question,” were largely inspired by her students that day. “I understood in that moment that you cannot assume someone does not also experience anxiety simply because their way of talking about it may not be the same as yours.”

震盪波說:「這實際上是一次集體崩潰,與我經歷過的任何事情都不一樣。」她的播客和書籍《氣候焦慮和兒童問題》很大程度上受到了那天她的學生的啟發。 “那一刻我明白,你不能僅僅因為某人談論焦慮的方式可能與你不同,就認為他們沒有經歷過焦慮。”

It doesn’t help, she added, that many people don’t realize what they’re feeling is climate anxiety because the way we talk about it tends to center the experiences of white and more privileged people — people who have been insulated from oppression and have rarely (until now) had to worry about the safety of their own future.

她補充說,許多人沒有意識到他們的感受是氣候焦慮,這並沒有幫助,因為我們談論它的方式往往集中於白人和更有特權的人的經歷——那些免受壓迫的人並且(直到現在)很少需要擔心自己未來的安全。

“For a lot of people, climate anxiety looks a certain way: It looks very scared, it looks very sad, and it looks like a person who is ready, willing and able to talk about it,” Sasser said. “But for those who are experiencing many compounding forms of vulnerability at the same time, you can’t just pick out one part of it and say, ‘Oh, this is what’s causing me to feel this way.’”

「對很多人來說,氣候焦慮看起來是這樣的:看起來非常害怕,看起來非常悲傷,而且看起來像是一個已經準備好、願意並且能夠談論它的人,」Sasser 說。 “但對於那些同時經歷多種複合形式的脆弱性的人來說,你不能只挑出其中的一部分並說,’哦,這就是讓我有這種感覺的原因。’”

A brave first step is to acknowledge privilege — and to support, and perhaps even learn, from those who have had to be resilient long before climate change became so overwhelming.

勇敢的第一步是承認特權,並支持那些早在氣候變遷變得如此勢不可擋之前就必須保持韌性的人,甚至可能向他們學習。

(特權,Intersectionality / (歧視的)交叉性的中心,去看【推文】Yuri Bezmenov's Ghost - [______] think they have a special insight into the way the world works)

“For me, this work is a matter of survival,” said Kevin J. Patel, who grew up in South L.A. and has been fighting for climate justice since he was 11. He was contemplative, nodding, when I shared what I learned from Sasser, and he gently added that one privilege many communities don’t have is the ability to turn it off. Not everyone can go on a vacation or take a day to recharge, he said. Even having the time to talk about your sadness can be a luxury.

「對我來說,這項工作關係到生存,」凱文·J·帕特爾(Kevin J. Patel) 說。當我分享我從中學到的東西時,他若有所思,點點頭。他說,並不是每個人都可以去度假或抽出一天的時間來充電。即使有時間談論你的悲傷也是一種奢侈。

Patel learned at a young age that not all communities get the same level of care. Growing up with hazy air, in a neighborhood hemmed in by the 10 and 110 freeways, Patel almost collapsed one day in front of his sixth-grade class when his heart suddenly started pounding at more than 300 beats per minute.

帕特爾年輕時就了解到,並非所有社區都能得到同等程度的照護。帕特爾在空氣霧霾中長大,周圍環繞著10 號和110 號高速公路,有一天,他在六年級班級面前差點崩潰,當時他的心臟突然開始以每分鐘300 多次的速度狂跳。

His parents, farmers from Gujarat, India, rushed Patel to the emergency room and held his hand while everyone around him thought he was dying. After months of hospital visits and procedures, doctors determined that he had developed a severe heart condition in large part due to the smog.

他的父母是來自印度古吉拉特邦的農民,他們將帕特爾送往急診室,並握住他的手,而周圍的人都認為他快要死了。經過幾個月的醫院就診和手術後,醫生確定他患有嚴重的心臟疾病,很大程度上是由於煙霧造成的。

As he learned to live with an irregular heartbeat, he found joy in his family’s tiny garden and marveled at all the ladybugs that gathered on the tulsi, a special type of basil. He taught his classmates that food came from the ground, not the grocery store, and together, they went on to form an environmental club.

當他學會如何適應不規則的心跳時,他在家裡的小花園裡找到了樂趣,並對聚集在圖爾西(一種特殊的羅勒)上的瓢蟲感到驚訝。他告訴同學們,食物來自地下,而不是雜貨店,他們一起組成了一個環保俱樂部。

Today, Patel speaks with the hardened wisdom of someone who has experienced much more than the typical 23-year-old. He’s constantly doing something — whether it’s supporting a neighbor, getting water bottle refill stations installed at his school, or turning the idea of a Los Angeles County Youth Climate Commission into reality. For years, he has guided other marginalized youth through OneUpAction, a grassroots environmental group that he built from the ground up.

如今,帕特爾的演講充滿了堅定的智慧,他的經歷比一般 23 歲的年輕人要豐富得多。他不斷地做一些事情——無論是支持鄰居、在學校安裝水瓶補充站,還是將洛杉磯縣青年氣候委員會的想法變成現實。多年來,他透過他白手起家建立的草根環保組織 OneUpAction 指導其他邊緣化青年。

Even if he doesn’t call it anxiety, he admits he sometimes has trouble focusing, and there’s a tenseness in his body that can be hard to shake off. But he’s usually able to turn it around by talking to his friends or elders, or by reciting his favorite proverb:

即使他不稱之為焦慮,他也承認自己有時難以集中註意力,而且身體裡有一種難以擺脫的緊張感。但他通常能夠透過與朋友或長輩交談,或背誦他最喜歡的諺語來扭轉局面:

They tried to bury us, but they didn’t know we were seeds.

他們試圖埋葬我們,但他們不知道我們是種子。

“It’s not about what I need, it’s about what my community needs,” he said. “There is joy in caring for one another. There is joy in coming together to fight for a future that we believe in.”

「這不是關於我需要什麼,而是關於我的社區需要什麼,」他說。 「互相照顧是一種快樂。聚集在一起為我們所相信的未來而奮鬥是一種快樂。

When talking about climate anxiety, it’s important to differentiate whether you’re assessing these emotions as a mental health condition, or as a cultural phenomenon.

在談論氣候焦慮時,重要的是要區分您是將這些情緒視為一種心理健康狀況還是一種文化現象。

Let’s start with mental health: Polls show climate anxiety is on the rise and that people all around the world are losing sleep over climate change. Organizations like the Climate-Aware Therapist Directory and the American Psychiatric Assn. have put together an increasing number of guides and resources to help more people understand how climate change has affected our emotional well-being.

讓我們從心理健康開始:民意調查顯示,氣候焦慮正在加劇,世界各地的人們都因氣候變遷而失眠。氣候意識治療師名錄和美國精神醫學會等組織。匯集了越來越多的指南和資源,幫助更多的人了解氣候變遷如何影響我們的情緒健康。

Just knowing that climate change is getting worse can trigger serious psychological responses. And the shock and trauma are all the more great if you’ve already had to live through the kinds of disasters that keep the rest of us up at night.

只要知道氣候變遷正在惡化就會引發嚴重的心理反應。如果你已經經歷了讓我們其他人徹夜難眠的各種災難,那麼震驚和創傷就會更加嚴重。

It’s also important to note that social media has magnified our sense of doom. What you see on social media tends to be a particularly intense and cherry-picked version of reality, but studies show that’s exactly how the vast majority of young people are getting their information about climate change: online rather than in school.

同樣重要的是要注意社交媒體放大了我們的厄運感。你在社群媒體上看到的往往是現實的一個特別強烈和精挑細選的版本,但研究表明,這正是絕大多數年輕人獲取有關氣候變遷資訊的方式:在網路上而不是在學校。

But you can’t treat climate anxiety like other forms of anxiety, and here’s where the cultural politics come in: The only way to make climate anxiety go away is to make climate change go away, and given the fraught and deeply systemic underpinnings of climate change, we must also consider this context when it comes to our climate emotions. How we feel is just as much a product of the narratives that have shaped the way we perceive and respond to the world.

但你不能像對待其他形式的焦慮一樣對待氣候焦慮,這就是文化政治的用武之地:消除氣候焦慮的唯一方法就是消除氣候變化,並且考慮到氣候問題令人擔憂且深刻的系統性基礎變化,當涉及到我們的氣候情緒時,我們也必須考慮這個背景。我們的感受同樣是敘事的產物,這些敘事塑造了我們感知和回應世界的方式。

“Climate anxiety can’t be limited to just a clinical setting — we have to take it out of the therapy room and look at it through a lens of privilege, and power, and the economic, historical and social structures that are at the root of the problem,” said Sarah Jaquette Ray, whose book “A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety” is a call to arms to think more expansively about our despair. “Treating a person’s climate anxiety without challenging these systems only addresses the symptoms, not the causes... and if white or more privileged emotions get the most airtime, and if we don’t see how climate is intersecting with all these other problems, that can result in a greater silencing of the people most impacted.”

「氣候焦慮不能只限於臨床環境——我們必須將其帶出治療室,並透過特權、權力以及其根源的經濟、歷史和社會結構的視角來看待它莎拉·雅奎特·雷(Sarah Jaquette Ray) 說,她的書《氣候焦慮實地指南》呼籲人們更廣泛地思考我們的絕望。 「在不挑戰這些系統的情況下治療一個人的氣候焦慮只能解決症狀,而不是原因......如果白人或更特權的情緒得到最多的關注,如果我們沒有看到氣候與所有這些其他問題的交叉,這可能會導致受影響最嚴重的人更加沉默。

(關鍵詞:白人、特權、交叉)

Ray, an environmental humanist who chairs the environmental studies program at Cal Poly Humboldt, also emphasized that our distress can actually be a catalyst for much-needed change. These emotions are meant to shake us out of complacency, to sound the alarm to the very real crisis before us. But if we don’t openly talk about climate anxiety as something that is not only normal but also expected, we run the risk of further individualizing the problem. We already have a tendency to shut down and feel alone in our sorrows, which traps us into thinking only about ourselves.

擔任加州州立大學洪堡分校環境研究計畫主席的環境人文主義者雷也強調,我們的痛苦其實可以成為急需的改變的催化劑。這些情緒是為了讓我們擺脫自滿情緒,為眼前真正的危機敲響警鐘。但如果我們不公開談論氣候焦慮,認為它不僅是正常現象,而是意料之中的事情,我們就有可能進一步將問題個體化。我們已經有一種封閉的傾向,在悲傷中感到孤獨,這使我們陷入只考慮自己的境地。

“One huge reason why climate anxiety feels so awful is this feeling of not being able to do anything about it,” Ray said. “But if you actually saw yourself as part of a collective, as interconnected with all these other movements doing meaningful things, you wouldn’t be feeling this despair and loneliness.”

「氣候焦慮讓人感覺如此糟糕的一個重要原因是這種無能為力的感覺,」雷說。 「但如果你真的將自己視為集體的一部分,與所有其他做有意義的事情的運動相互聯繫,你就不會感到這種絕望和孤獨。”

The trick to fixing climate anxiety is to fix individualism, she said. Start small, tap into what you’re already good at, join something bigger than yourself.

她說,解決氣候焦慮的秘訣是解決個人主義。從小事做起,挖掘你已經擅長的事情,加入比你自己更大的事情。

And by fixing individualism, as many young activists like Patel have already figured out, we just might have a better shot at fixing climate change.

正如帕特爾這樣的許多年輕活動家已經認識到的那樣,透過解決個人主義問題,我們可能更有機會解決氣候變遷問題。

Let us consider, for a moment, how the words that we use can also limit the way we think about our vulnerability and despair.

讓我們考慮一下,我們使用的字詞也能限制我們思考我們的脆弱和絕望的方式。

Something as simple as the “climate” in “climate anxiety” and how we define “environment” can unintentionally reinforce who we center in the conversation.

像「氣候焦慮」中的「氣候」這樣簡單的事情以及我們如何定義「環境」可以無意中強化我們在對話中的中心地位。

“In Nigeria, what we call our environment — it’s not just trees and mountains — it’s also about our food, our jobs, the biodiversity that gives us the life support that we need to thrive every day. That’s what we call our environment; it’s about our people,” said Jennifer Uchendu, who founded SustyVibes, a youth-led sustainability group based in her home country, as well as the Eco-Anxiety in Africa Project, which seeks to validate the emotions and experiences of communities often overlooked in climate conversations. “So if people are being oppressed by the system, it is still linked to our idea of the environment.”

「在尼日利亞,我們所說的環境——不僅僅是樹木和山脈——還關係到我們的食物、我們的工作、為我們提供每天蓬勃發展所需的生命支持的生物多樣性。這就是我們所說的環境; Jennifer Uchendu 說道,她創立了 SustyVibes(一個在她的祖國由青年領導的可持續發展組織)以及非洲生態焦慮項目,該項目旨在驗證在非洲國家中經常被忽視的社區的情緒和經歷。 。 “因此,如果人們受到制度的壓迫,它仍然與我們的環境觀念有關。”

Many of Uchendu’s elders have expressed a lifetime of feeling frustrated and powerless, for example, but she said they didn’t immediately connect these feelings to climate change because “climate anxiety” sounded to them like a new and elite phenomenon.

例如,烏成杜的許多長輩都表示一生都感到沮喪和無能為力,但她說,他們並沒有立即將這些感覺與氣候變遷聯繫起來,因為「氣候焦慮」對他們來說聽起來像是一種新的精英現象。

We hear so often today that climate change is the existential crisis of our time, but that dismisses the trauma and violence to all the people who have been fighting to survive for centuries. Colonization, greed and exploitation are inseparable from climate change, Uchendu said, but we miss these connections when we consider our emotions only through a Western lens.

今天我們經常聽到氣候變遷是我們這個時代的生存危機,但這卻忽視了幾個世紀以來為生存而奮鬥的所有人所遭受的創傷和暴力。烏琴杜說,殖民、貪婪和剝削與氣候變遷密不可分,但當我們僅透過西方視角來考慮我們的情緒時,我們就會錯過這些連結。

(「殖民、貪婪和剝削與氣候變遷密不可分」實際上是「氣候正義」,引用【長片系列 - Changing Tides Ep. 1】Climate Justice | James Lindsay & Michael O'Fallon)

我們應先從「正義」開始,它指makes things fair(令事物變得公平),氣候正義是指(1)對於有關氣候的公平性及(2)氣候如何變化及其影響,但相關學術文獻沒有清楚定義氣候正義,所以在此只能提供一些例子

例如某些國家在工業化過程中造成相當污染,這些國家因工業化而富裕起來,得到取得很多Power(權力?)、資源及財富,而較貧窮國家並沒有得到那些資源財富等又同時地沒製造那麼多污染,但氣候變化影響所有國家,氣候變化對較貧窮國家的影響是「不正義的」因為他們沒製造那麼多污染卻沒得到工業化後的好處,所以應該把工業化國家的資源、機會重新分配到較貧窮國家,例如以金錢、救濟物資、開放移民等方式

For Jessa Calderon, a Chumash and Tongva songwriter, these disconnects are ever-present in the concrete-hardened rivers snaking through Los Angeles, and the sour taste of industrialization often singeing the air. In her darkest moments, her heart hurts wondering if her son, Honor, will grow up to know clean water.

對於 Chumash 和 Tongva 歌曲作家 Jessa Calderon 來說,這些脫節在蜿蜒穿過洛杉磯的混凝土硬化河流中始終存在,工業化的酸味常常燒焦空氣。在她最黑暗的時刻,她的心很痛,想知道她的兒子奧諾長大後是否會懂得乾淨的水。

Her voice cracked as she recalled a brown bear that had been struck dead on the freeway near the Cajon Pass. As she watched strangers gawk at the limp body and share videos online, she wished she had been able to put the bear to rest and sing him into the spirit world.

當她想起一隻在卡洪山口附近的高速公路上被撞死的棕熊時,她的聲音沙啞了。當她看到陌生人呆呆地看著這隻熊癱軟的身體並在網路上分享影片時,她希望自己能讓這隻熊安息,並用歌聲讓他進入精神世界。

“If we don’t see them as our people, then we have no hope for ourselves as a people, because we’re showing that we care about nothing more than ourselves,” she said. “And if we care about nothing more than ourselves, then we’re going to continue to devastate each other and the land.”

「如果我們不把他們視為我們的人民,那麼我們作為一個人民就沒有希望,因為我們表明我們只關心自己,」她說。 “如果我們只關心自己,那麼我們將繼續摧毀彼此和土地。”

It is not too late to turn your climate anxiety into climate empathy. Acknowledging the emotional toll on people beyond yourself can be an opportunity to listen and support one another. Embracing our feelings — and then finding others who also want to turn their fear into action — can be the missing spark to much-needed social and environmental healing.

現在將氣候焦慮轉化為氣候同理心還為時不晚。承認自己以外的人所遭受的情感損失可能是一個相互傾聽和支持的機會。擁抱我們的感受——然後找到其他也想將恐懼轉化為行動的人——可能是急需的社會和環境療癒所缺少的火花。

There is also wisdom to be learned in the songs and traditions of past movements, when people banded together — for civil rights, for women’s suffrage — and found ways to keep hope alive against all odds. And the more we look to the young people still caring for their elders in Nigeria, and to our Indigenous neighbors who continue to sing and love and tend to every living being, the better we might also comprehend the resilience required of all of us in the warming years ahead.

當人們為了民權、為了婦女選舉權而團結起來,並找到克服一切困難保持希望的方法時,從過去運動的歌曲和傳統中也可以學到智慧。我們越多關注尼日利亞仍在照顧長輩的年輕人,以及繼續唱歌、關愛和照顧每一個生命的原住民鄰居,我們就越能理解我們所有人在這個國家接下來繼續暖化日子所需要的韌性。

So how should we cope? For Patel, living with his irregular but unwavering heartbeat, he finds strength in the words of adrienne maree brown, who famously wrote in “Emergent Strategy” that in the same way our lives are shaped today by our ancestors, we ourselves are future ancestors. Calderon, who similarly taught her son to leave this Earth better with every passing generation, confided to me that on the days when the sorrow feels too great, she sneaks off to plant native manzanita seeds in neighborhoods stripped of plants and trees.

那我們該如何應對呢?對帕特爾來說,他的心跳不規則但堅定不移,他從艾德麗安·瑪麗·布朗的話中找到了力量,她在《緊急戰略》中寫道,就像我們今天的生活是由我們的祖先塑造的一樣,我們自己也是未來的祖先。卡爾德隆也同樣教導她的兒子在每一代人中都要更好地離開這個地球,她向我透露,在悲傷感太強烈的日子裡,她會偷偷地去那些沒有植物和樹木的社區種植當地的曼薩尼塔種子。

As I’m reminded of all the love we can still sow for the future, I think of Phoenix Armenta, a longtime climate justice organizer in Oakland who has inspired numerous people, including myself, to take heart in all the times we actually got it right. (Remember acid rain? It was a huge problem, but collective action inspired multiple countries to join forces in the 1980s, and we did what needed to be done.)

當我想起我們仍然可以為未來播下的所有愛時,我想到了菲尼克斯·阿門塔(Phoenix Armenta),他是奧克蘭的一位長期氣候正義組織者,他激勵了包括我在內的無數人,在我們真正得到它的時候振作起來。 (還記得酸雨嗎?這是一個巨大的問題,但集體行動激勵多個國家在 20 世紀 80 年代聯合起來,我們做了需要做的事情。)

(我都不用說服人們這是「氣候正義」了,它本身就直接寫出來…)

“Imagine what kind of world you actually want to live in and start working to make that happen,” said Armenta, who recently made the switch to government planning to help more communities find their voice and determine their own visions for the future.

「想像你真正想要生活在什麼樣的世界,並開始努力實現這一目標,」阿門塔說。

To grieve the world as we know it is to miss out on opportunities to transform our world for the better. To believe we have nothing left to hope for is a self-fulfilling void. We must find the courage to care, to change, to reimagine the systems that got us into such a devastating crisis in the first place — and we must allow ourselves to dream.

讓我們所知道的世界感到悲傷,就等於錯過了讓我們的世界變得更美好的機會。相信我們已經沒有什麼希望了,這就是一種自我實現的空虛。我們必須找到勇氣去關心、去改變、去重新構想那些原本讓我們陷入如此毀滅性危機的體系──而且我們必須允許自己去夢想。

“But it can’t just be my dream, or your dream. It has to be our collective dream,” Armenta said. “I’ve known for a very long time that I can’t save the world, but we can save the world together.”

「但這不僅僅是我的夢想,也不僅僅是你的夢想。這必須是我們的共同夢想,」阿門塔說。 “我很早就知道我無法拯救世界,但我們可以一起拯救世界。”

喜欢我的作品吗?别忘了给予支持与赞赏,让我知道在创作的路上有你陪伴,一起延续这份热忱!

- 来自作者

- 相关推荐