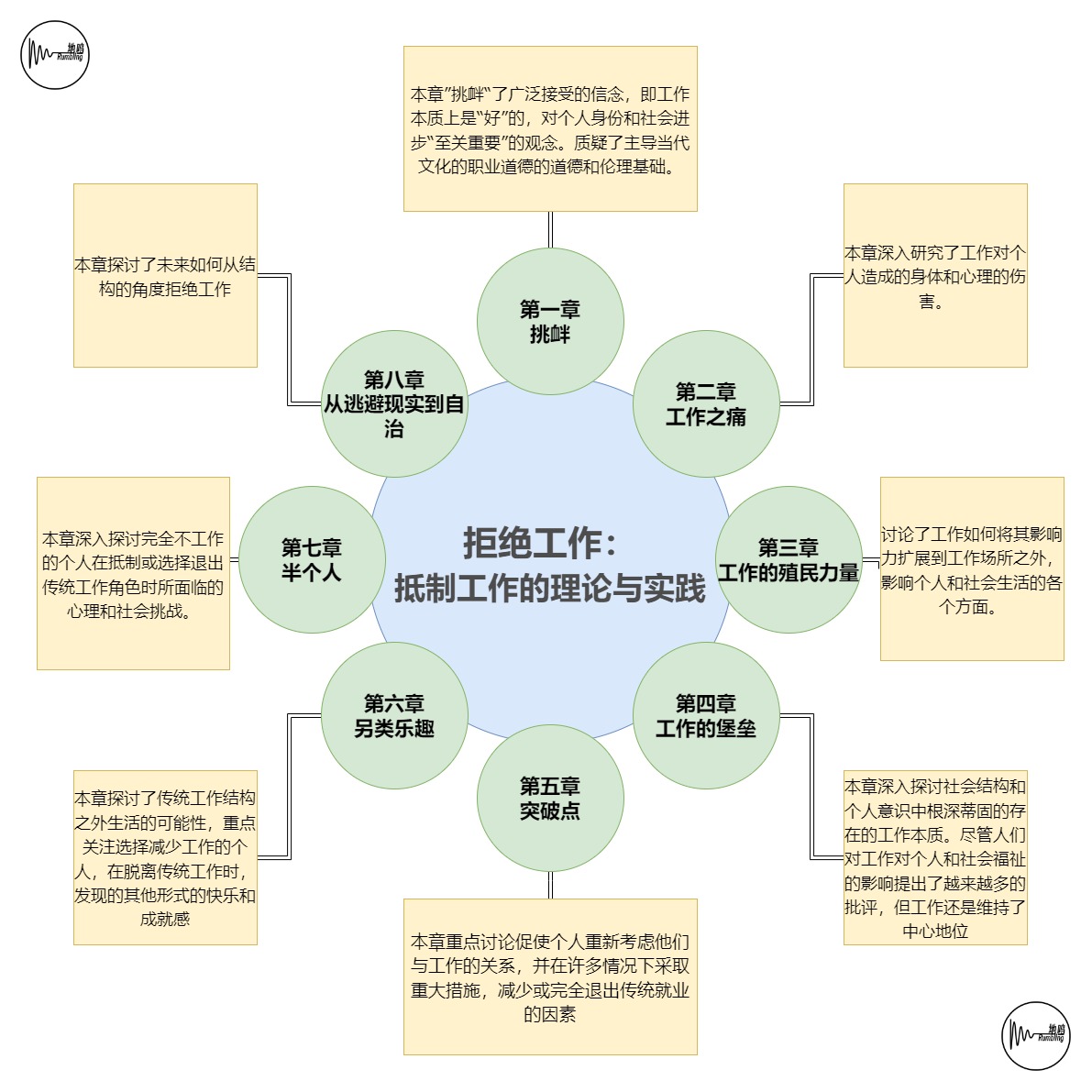

Refusing to Work: Theory and Practice of Work Resistance丨Labor Day

Compiled by: Mustard seeds, shrimp

Comparison: mustard seeds, shrimp

David Frayn points out that "as long as economic rationality continues to dictate the goals and methods of production, existing attempts to humanize working conditions are very limited in what they hope to achieve" (p46).

David Frayn reviews a series of theoretical studies on the alienated nature of industrial labor by scholars after Marx, which expand the external details of the alienation brought about by work in history.

“We hated the place and despised everything it stood for, but we feared being ‘released’ into an economic vacuum where we would struggle to find work and would have to appear equally welcoming, compliant and flexible to other potential employers. I often arrived at the warehouse in the mornings with a mixture of relief that I still had a job and disappointment that the place had not been washed away in some way during the night.”

—Ivor Southwood – Unbroken Inertia (2011)

Due to the development of technology, many people once believed that the transformation to a new knowledge-based economy would make the future brighter - these emerging forms of employment would provide opportunities for humanized work. However, in our current world, David Frayn said that alienated forms of mechanical labor still have a strong "continuity" in terms of the organization and experience of the labor process itself - in the computer age, Taylorism continues to exist because workers continue to be timed, micro-managed, and forced to perform small, repetitive tasks by profit-driven production systems.

Compared to the obvious physical alienation brought by work, another kind of emotional work alienation is more hidden. With the rise of service work, attempts to micromanage employees' emotional behavior have also increased. Some more implicit cultural management strategies also try to encourage workers to fully identify with their work roles - trying to "dress up" alienated labor with a fun and free language. In each case, work seems to offer the promise of becoming more "free" or "human" - providing people with the opportunity to use their communication skills; feel a sense of belonging in the organization; be themselves; and have fun at work. David Frayn refuted these emerging phenomena one by one.

The first is "values". In the pursuit of profit, companies often invest a lot of money to shape the values and identity of employees, align them with the company's expectations, and make them believe that they are doing something valuable and strive for it. In fact, David Frayn said that the "valuable" jobs provided by capitalist companies are not determined by human needs for an environment to do interesting work, but by whether these jobs are profitable for the company.

The second is the promotion of "family" or "team". By promoting identification with work through organizational rhetoric around concepts such as "team" and "family", companies aim to encourage employees to inspire dedication. Casey suggests that the role of concepts such as "team" and "family" is to redefine the workplace as a moral realm rather than an economic realm, thus linking employees more closely to organizational goals (p57). David Frayn quotes Gorz, who points out the fact that "workers are not part of the corporate family, but disposable tools to create private interests" (p63).

There is also a promotion of “individualisation” . The author of a popular management guide writes that “people are more productive and give more when they are happy and free to be themselves” (p59), and David Frayn gives several examples, such as the inclusion of perches in modern London offices, which include various leisure facilities and living rooms, designed to make employees feel like “working from home” while staying in the office. David Frayn suggests that what is telling is the extent to which workers are allowed to “be themselves”, and it is certain that this right to “be themselves” does not extend to the right to be passive or unhappy (p59). Even if the work is enjoyable, working full-time still usually means: on the one hand, a person may find temporary comfort in calling himself a teacher, a bar manager or a policeman, but none of these identities can describe who the self really is - no matter how hard a person tries to achieve self-realisation by adopting a work role, he will always fail; on the other hand, the narrow focus of our skills and abilities on one activity, to the exclusion of others, will usually still restrict us to a prescribed and defined role in the economic system , silencing the parts of ourselves that cannot serve our assigned position in the capitalist production process.

David Frayn concludes by identifying these new alienated forms of work. He argues that “paid work” is less an exercise of productive and creative capacities than an obstacle to the development of these capacities. If creative, meaningful work is no longer synonymous with what people do in paid work, then it makes sense from a humanistic or liberationist perspective to begin exploring the possibility of reducing work and expanding leisure time. Working less might allow people’s talents to be more developed elsewhere—in informal production networks outside the narrow confines of the job roles provided by the capitalist economy (p66).

Why do we have so little leisure time, and why is the leisure time we do have often filled with a sense of responsibility and anxiety? (p69) David Frayn further asks, when unemployment has become "job hunting" - itself a form of work - how much time can we confidently call our own? When, exactly, will we be truly free from the need to produce or consume economic wealth and truly free to experience the world and its cultures?

What's the problem?

The first is the fragmentation of time brought about by the standard work system. David Frayn starts with the simple question: When does the work day really end? Although our jobs may require us to work a certain number of hours each day, it is clear that we do not simply walk out of the workplace and enter a free world . Adorno was one of the first scholars to study the colonization of daily life by work. As Adorno shows, free time is not truly free at all as long as it is still guided by the forces that people are trying to escape. In this degraded free time, self-defined activities outside of work are often limited to "hobbies": trivial activities to kill our own meager time. Adorno strongly opposes the word "hobby" , arguing that it devalues unpaid activities (p71).

David Frayn suggests that the standard eight-hour workday breaks free time into fragments (p71). Full-time workers experience time as a series of rapid discrete pockets: a constant cycle of work and free time, with free time limited to even days, weekends, and holidays. The extreme victim of this situation is today's typical hurried worker, who commutes home in the dark, with unanswered emails, exhausted, unable to connect emotionally with family, and unwilling to do much except drink and watch TV before bed (the point here is not that drinking or watching TV are "low-level" activities, but that workers are deprived of the time and energy to choose other means). As Graber shows, technologies such as email or instant messaging, whose best design feature is to allow asynchronous communication, ultimately have the opposite effect on today's busy employees, who feel pressured to be "always present, responsive, and available" both in and out of the office (p72).

On the other hand, it comes from the myth of employability. Under this myth, each individual has the responsibility to improve his or her prospects through training, obtaining educational credentials, building interpersonal networks, learning how to show the right personality, and gaining life experience that matches the values sought by employers. David Frayn says that the concept of employability has risen to a remarkable prominence in the early 21st century and it constitutes the key to neoliberal political philosophy (p73). Sennett, Beck, and Bauman popularized the view that capitalist society is moving towards insecurity (p73). Employment insecurity affects almost anyone. The most insecure people include undocumented immigrant workers who are illegally employed and paid meager wages, to single parents who worry about losing their welfare rights. It also extends to creative or academic workers who may face a future full of short-term difficulties.

Thus, in order to protect ourselves from the vortex of unemployment and low-quality, low-paying jobs, for many people, the development of employability becomes a lifelong “career” in itself – when the development of employability becomes a practical necessity and a primary mental concern, we become increasingly committed to doing what needs to be done rather than doing it because the activity has intrinsic value, while at the same time, as Bogdan Costea argues, the discourse of employability can engender in workers an uneasy sense of “endless potential”; every worker is taught that he or she can always do more; on the other hand, irrelevant traits must be smoothed over , as Hadar Elraz argues, personal traits that are inconsistent with the image of a model worker – shyness, moodiness, emotional sensitivity – must all be smoothed over in order to present a marketable self that is non-aggressive, responsible, graspable, and, most importantly, “hireable” (p77).

David Frayn suggests that “employability” embodies a novel power dynamic because, in a sense, individual sacrifice for one’s own benefit is self-imposed. Unlike traditional exploitation, which is limited to punching a clock and controlled externally through the boss’s coercive discipline and technology, the discipline required by “employability” is continuous and requires constant self-regulation. Employability represents a “decentralized” form of exploitation, where people are forced to submit in an almost voluntary manner, as the spatial and temporal boundaries that previously limited exploitation to the time spent on the work clock are dissolved (p78).

Next, the author further spent a lot of space to sort out and analyze theories such as consumerism. David Frayn showed that all this means that consumer demand is exaggerated, and the market's encirclement of individuals and the exaggeration of consumer demand are one of the main mechanisms for capitalism to continue to mobilize against the possibility of reduction (p92). Strong consumer demand increases people's dependence on income obtained through work. Capitalism has taken us on a path - the utopian dream of everyone enjoying comfort and leisure is buried under mountains of goods.

David Frayn concludes this colonization of life by work : when most of our time is spent working, recovering from work, compensating for work, or doing the many things necessary to find, prepare for, and stick to work, it becomes increasingly difficult to tell how much of our time is truly our own; many of our current activities seem to be designed to ensure our survival now and in the future, rather than because the activities themselves are valuable; the agents of capitalism force us to accept the dividends of productivity growth in the form of more consumption rather than more leisure time. If the development of production technology has theoretically created the possibility of reducing working hours, the practical possibility of reducing work continues to be hindered by the principle of sustained economic growth and by capitalism's constant efforts to press our leisure time into the hands of consumption (p94).

In Chapter 4, David Frayn examines the ideology of the sanctity of “hard work” combined with a virulent demonization of non-workers and others who resist professional work . As David Frayn will show, the power of these ideas lies not only in their ubiquity in the media but also in their placement in a range of social policies that significantly reduce the freedom to resist work.

David Frayne first discusses the "stigma" against the unemployed. He points out that today, keeping a job is still widely seen as a sign of independence, maturity and good character, and hard work still represents an appropriate lifestyle and proves one's commitment to national prosperity (p98). David Frayne uses the UK as an example: Cameron often describes welfare applicants as wasters who "sit on the sofa waiting for their benefits to arrive", "We are building a country for those who work and want to keep moving forward. We say to every hard-working person in our country: We are on your side." David Frayne suggests that these governments' repeated references to hard work (always defined as paid employment) have constructed a rigid "dichotomy" in the public imagination - one side of this dichotomy is those upright, hard-working citizens who help ensure the future of the country, and the other side is those morally questionable unemployed people who do nothing. Which one are you? A layabout or an employee, a shirker or a worker? Do you do something, or do nothing? This technique of splitting the population into binary oppositions has long been used as a method of social discipline , whether we are talking about crazy and sane, normal and abnormal, or dangerous and harmless. David Frayn further argues that the tendency is for recognition of the structural causes of unemployment to fade away, and poverty to be seen as the inevitable result of poor self-management . Even in areas where the number of unemployed people greatly exceeds the number of available jobs, people still believe that if a person behaves a little better, puts in a little more effort, or simply believes in himself, he or she can find a job and escape poverty (p100).

He further cites many examples of biased media coverage of workers’ strikes, suggesting that the moral barriers around work are very strong. Any worker who crosses the line is quickly treated as a dangerous outsider and deprived of a political voice. The political significance of the act of resistance is weakened by portraying the rebels as “sick” and shifting public attention from the political cause to the alleged psychology of the rebels .

In this case, resistance is not about the inequality of the capitalist labor process, but rather about personal issues within the worker—a negative attitude, an inability to be a team player, or a tendency to shirk responsibility. In other words, the temporary pathology of work is pushed onto the worker and internalized as a personal trait.

—Fleming and Spicer, 2003

A series of personal, social and environmental crises has given us a powerful opportunity to question the role and importance of work in modern society, but the relentless “moralization” of work confines us to consistent thinking circuits.

David Frayn criticizes the simplicity of the deprivation model , which has a wide influence on the study of unemployment. In this model, unemployment is reduced to a flawed state of existence, contrary to the normal and ideal state of employment . David Frayn argues that the suffering of the unemployed in the model is seen as evidence that paid employment must be a remedy, but the benefits of employment are only invoked in the abstract, without being complicated by the actual situation of good and bad jobs (p109). On the other hand, it treats the unemployed as a single type, suggesting that unemployment is inherently miserable, and thus strongly implies that humans should work because it is normal and natural to do so (p109). David Frayn criticizes this attempt to generalize the types of unemployed.

Next, David Frayn gives an example of a thought experiment:

In seminars, I try to get students to think about the reasons why we work today by asking them if they would still work if they won the lottery. Perhaps surprisingly, almost all students usually say they would. It is easy to get upset with them because of this apparent lack of imagination.

(p111)

David Frayn goes on to cite Weber and Russell, saying: In many ways, students’ attachment to the idea of work is entirely justified – in contemporary capitalism, the idea of public life has become so synonymous with paid work that it is difficult to imagine any other way in which one could transcend the isolation of a purely private life (p111).

It seems most likely that the reason why people continue to show such a strong willingness to participate in the labor process stems directly from the fact that they have no practical alternatives.

——(Ransome, 1995)

David Frayn concludes that the felt need for work is strongly influenced by sociopolitical, economic, and moral choices. There is nothing in a human being 's innate psychological makeup that makes it necessary for him or her to be a paid employee. In today's work-centered society, unemployment is undoubtedly a terrible experience for most people, but this does not tell us much about a hypothetical future society in which work is no longer the only source of income, power, and belonging . David Frayn asks: What if income could be decoupled from work, allowing everyone to benefit from a higher level of financial security? What if there were multiple ways to earn the respect of citizens besides through paid work? What if the increasing abundance of free time gave rise to a thriving infrastructure of informal social networks and self-organized production? Would my old students still feel so dependent on work? (p112)

Next, David Frayn reviews the history of resistance to work, including the workers' movements in Britain and France in the 19th century, the activities of hippies and punks in recent decades, and the activities of second-wave feminism in the 20th century - all in the name of mass "refusal to work" (p115) - this also includes the May Day movement in Europe - a collective of flexible workers, temporary workers and migrant workers across Western Europe - is such a movement, which gathers once a year to promote an alternative vision of development . The latest part comes from Gorz's research. David Frayn cites Gorz's concept of a "new proletariat" - a demographically diverse "non-working class" who realize that their time and abilities are wasted in employment and decide to seek satisfaction in other areas of life (p115). Gorz believes that the growing anti-work sentiment only constitutes a revolution in people's hearts and minds, but he believes that whether it will be transformed into a real social alternative remains to be seen (p116).

Beginning in Chapter 5, David Frayn introduces many of the work resisters he has met , explores their reasons for resisting work, and outlines how they use their time. In Chapters 6 and 7, he continues by exploring some of the joys and difficulties they encountered in trying to resist work. David Frayn seeks to understand one question: Why do participants feel the need to resist work? Or, perhaps more accurately, why do they choose to act on the need to resist work?

As an idler, I promise to…try not to work, especially not for corporate idiots; to let stress get to me as little as possible; to eat slowly; to drink real ale often; to sing more; to smile more; to get off the 9-to-5 merry-go-round before I get sick of it; to entertain myself in public and in private; to please others as well as myself; to know that work is only to pay the bills; to always remember that friends are a source of strength; to enjoy the simple things; to spend precious time in nature; to spend less on big business and corporations; to make lots of beautiful things; to go against the grain; to make a difference, no matter how small, in the world and in those around you.

——The selected commitment list of the Idle Alliance

Of the group I interviewed, four participants were associated with a group called the Idlers’ League (Jack, Mike, Annie, and Ellen). The group never tried to “do anything political” and was loosely defined and demographically diverse. Some of these people had reduced their work hours, some reduced them a lot, and some tried not to work at all . In addition to the four idlers, I met fifteen other people, each with different backgrounds, situations, and aspirations.

In Adam ’s case, he gave up a high-paying job as a computer programmer in favor of teaching English part-time in Japan and doing a small amount of freelance programming work;

In Samantha ’s case, she gave up her high-paying job as a patent attorney (much to her mother’s horror) for a more leisurely lifestyle as a part-time waitress and private tutor;

Of all the people, perhaps Larry displayed the most “humble” act of resistance. He was a social worker who had the courage to ask his managers to reduce his workweek by one hour (from 8 to 7)—a proposal to which they agreed. Larry’s modest goal was simply to feel less rushed and stressed in his daily life (p120).

David Frayn works hard to show the complexity of this group : while some say they live quite comfortably on part-time wages, previous earnings or their partners’ income, many make significant sacrifices to resist work – sustaining themselves through meager savings, odd jobs, community reciprocity, loans and state benefits. There is also a great deal of variation in the level of convictions of each individual.

David Frayn interviewed members of the Idlers' League, some of whom were setting up stalls at a local market in southeast England. Jack, a modest man in his thirties, initially seemed reluctant to participate. He didn't seem to believe that his view of the world was worth traveling halfway across the country.

Jack explained that he had switched his librarian job to part-time hours to gain more free time:

I thought 'wait a minute', there's more to life than just a 9-to-5 job and commuting and stuff like that, there's got to be more to it'. So I was drawn to the idea of 'doing less', a model where I would work half the day and be alone the rest of the time.

Jack expressed a strong desire to engage in creative work, but believed that this desire was stifled in his previous full-time job. He outlined his belief that creativity is developed through a leisurely lifestyle, a life filled with conversation and reading, but regrettably his previous job prohibited him from doing these things regularly. The purpose of switching to part-time work was to reduce exhaustion and hopefully rediscover his desire for creative activity. He particularly enjoys writing and is pleased to announce that he is finding time to write again.

The trouble is, once it happens, you can't really look at things any other way because it's almost like you've seen something - it's like actually seeing through disguise. It's a bit like adults realizing there is no Santa Claus.

Another idler, Mike, talked about how, in his thirties, he “saw through” the work ethic that had been instilled in him by his teachers at school. Participant Eleanor came to believe that “we’re really just socially constructed to think that we’re supposed to work all the time, make a lot of money, and do all these things.”

For whatever reason, to these people the need for employment seems to be a social construct rather than a fact of life.

Rachel , a woman in her early fifties, described her decision to switch from full-time to part-time work (as a human resources officer) as an attempt to “ take life off autopilot” ; Anne, who quit her high-commitment job in television to become a freelance photographer, described her decision as the product of “waking up from a long sleep” .

In a lengthy analysis of the content of the interviews, David Frayn suggests that whether people are reducing their working hours or giving up work altogether, they are not doing so based on some crude, anti-work ethic, but rather on a deep desire to do more. The stories people tell about their work suggest that the lack of meaning and autonomy in employment fuels a desire to resist. Functional social roles, such as paid work, can never be identical to the complex, well-rounded people forced to inhabit them. There is always a self that transcends social roles, wanting to break out . When the people David Frayn met were all working full-time, the work role always left certain desires unfulfilled, ambitions unsatisfied, skills dormant, and important parts of the self deprived of expression and recognition (p143).

David Frayn also suggests that for a minority, resistance to work seems closer to a necessity, or an act of self-preservation (p147).

Bruce provides the most poignant illustration of this. When we met, Bruce had given up on work altogether and could not imagine himself being well enough to hold down a job in the near future. Bruce had previously worked in a care home supporting people with severe mental health problems, but since quitting his job he has been claiming Employment Support Allowance to get by.

I was literally done. That's how I thought, a switch inside of me just went off and I was literally broken. Almost overnight I started having all these aches and cramps and twitches. I couldn't sleep. I started having joint pains, inflammation in my body, gut issues, vision issues, hearing issues. It was like my whole body was saying to me "enough". I now think that in the way I perceive mental illness, my body was yelling at me in the kindest way - I wasn't listening, so it yelled, it was saying "you really need to take a break and re-evaluate life and the way you are with yourself".

Similar situations arise in other cases. Anne says that her decision to become a freelancer and adopt a flexible work schedule was partly a desire to manage her fatigue and food allergies (as well as to have more free time to care for her sick father); in Lucy 's case, giving up work was explained as an attempt to live a calmer, less anxious life; and in Gerald 's family, his early retirement was partly an attempt to relieve anger and tension in his marriage (p151).

In a society where there is such a strong moral emphasis on being a working and economically active citizen, perhaps a more traditional response to physical and psychological distress is to ignore or suppress symptoms rather than interpret them as signals of social and environmental disharmony. David Frayn adds that this is often an act of self-protection , and that escaping the stress and routine of work is essential to their well-being (p154).

After analyzing the interviewees' voluntary choice and self-protection, David Frayn then conducts a detailed theoretical critique of the interviewees' concepts and consumerism in Chapter 6. Finally, David Frayn states: They resist capitalism's constant demands to feel shame and dissatisfaction with their property, and they are proud of their ability to develop their own concepts of happiness, beauty, sufficiency, and happiness. They are reflecting on the relationship between well-being and commodity consumption and discovering a new sense of control and rootedness in the world as they develop hitherto undiscovered self-reliance (p188).

In Chapter 7, David Frayn details more extreme cases of people who have attempted to live without work altogether . Married couple Matthew and Lucy (who have both given up work entirely) appear to struggle with feelings of inferiority as a result of being unemployed. Matthew argues that in the culture of affluent societies, people often compare not having a job to being an incomplete person:

I think a lot of people think that if you don't have a job, you're missing out on your shadow. It's like half a person, and it's a strong thing, but it's like the whole thing - like when we introduced ourselves to people last year. They'd ask "What do you do?" If you were unemployed, they'd ask "brrrrrr." People would kind of shudder and think, oh, so you really don't do anything.

Matthew was engaged in writing, but here was the problem: with no apparent social utility and no income, the time Matthew spent writing represented a potential source of embarrassment. In interviews, he did not think people would accept that his identity and daily life could be constructed around an unpaid activity.

A similar dilemma was faced for Samantha . Working as a lawyer had always been a source of pride for her parents, but from Samantha’s perspective, this pride was little more than a source of irritation . This was because Samantha did not truly identify with her work as a lawyer. While she engaged in practices associated with her work role, she had always refused to embody that role, that is, when she practiced as a lawyer, she hated being identified as a lawyer, with lawyer’s views, lawyer’s tastes, and lawyer’s behavior . Samantha rebelled against her parents and refused to accept that her decision to leave the world of professional employment was a sign of regression or immaturity . Instead, she developed her own notion of maturity based on assertions of autonomy and diversity rather than on the attainment and embodiment of work roles.

Living according to her values and staying in mainstream society was very difficult for Eleanor : “I feel like I’m always trying to defend my lifestyle, and I just don’t want to do that. I hate doing that.” Her solution was to live in an autonomous rural community, where she enjoyed being around people who shared her critical views on work and consumerism. She enjoyed belonging to a social circle where she wasn’t forced to constantly apologize and explain her actions and choices.

In every case David Frayn investigated, the subjects were judged negatively for their resistance to professional work. The people he met were judged by society to have failed the moral test of work in a more fundamental sense . Their unemployment was indicative of a deeper weakness of character. In a society where work is our primary means of acquiring a public identity, these people have a hard time convincing others that their choices and activities are meaningful and worthwhile (p199).

In the course of a lengthy analysis, the authors have shown us some of the ways in which resistance to work can be made tenable. We have seen ways in which dependence on income can be reduced in a pleasant way, and we have seen some of the strategies people use to insulate themselves from the stigma and isolation that comes with resistance to work in a work-centered society.

At the end of his investigation, David Frayn faces the question of whether and how individual cases of resistance to work observed in the interstices of society can be translated into meaningful and desirable social change for all (p209).

David Frayn steps beyond the stagnant work-life balance discussion to challenge the work-centric nature of modern society and question the traditional view that work is inherently beneficial or necessary for individual and social well-being.

In his final chapter, he suggests that the stories of the people he interviewed who resisted work demonstrate the power of individual agency . However, while the author acknowledges this, he ultimately insists that attempts to resist work on an individual basis are very limited (p217). David Frayn emphasizes the refusal of work from a structural perspective, arguing that everyone should work less and that everyone can benefit from increased free time . He argues that the "refusal" of work must be fought in collective and political conditions rather than on an individual basis; he also says that what he proposes is "a critique of the moral, material and political pressures on workers, rather than a series of judgments about the attitudes of the workers themselves" (p22).

Finally, he points out that the long-term goal is to rebuild society so that work is no longer an inviolable source of income, power, and belonging . He makes a beautiful vision: as free time is extended, people will use it to carry out a variety of productive and unproductive activities, each according to their own autonomous standards of beauty and practicality (p221). To do this, David Frayn believes that the long-term work is to open the door to discussion, actively pay attention to outsiders in society, join the debate, and finally defend the importance of imagination.

Where to go next is not an individual choice, but a social choice.

—David Frayn

*Di Ming is a co-creation group. If you want to join us and try to focus on some topics and expand the space for writing, please send us a private message.

We look forward to your joining us.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More