Year-end gift: Drawing the future on white paper (Episode 6) - Tolstoy or Zhang Xianzhong? No…

欢迎回来!这里是第6集。

If you missed it, you can see it below:

- " Year-End Rites: Drawing the Future on White Paper (Episode 1) - Are we "Iranian"? 》

- " Year-End Ceremony: Drawing the Future on White Paper (Episode 2) - The torch has been lit, what next? 》

- " Year-End Ceremony: Draw the Future on White Paper (Episode 3) - Compete for IQ with the rulers, not with the public "

- " Year-End Rites: Drawing the Future on a Blank Paper (Episode 4) - Yes, there is an uprising that is hard to suppress "

- " Year-End Gift: Drawing the Future on White Paper (Episode 5) - Smashing the Closed Loop "

Q: Translations of the works of Gene Sharp, the godfather of non-violence, began to circulate on the Internet when the paper was first released. I don’t know how to describe it. If you know who the suppressor you are facing is, you should hurry up now. Wear a bulletproof vest and a helmet instead of reading about nonviolence. I am not saying that non-violence is useless, and I am definitely not a fan of violence. I know that violence alone may be difficult to solve the problem, but the current situation is that everyone involved in this debate is trying to drag the topic into the so-called From a moral perspective, all kinds of Tolstoyans, this is wrong no matter what. I don’t understand the theory, but I know that morality cannot determine victory or defeat in the process of fighting bandits. Half are Tolstoyans and the other half are Zhang Xianzhongists. Does anarchism advocate violence or nonviolence? Is the "strategic consideration" you mentioned a conclusion? How to convince Tuo and Zhang?

iyp : Tolstoyists and Zhang Xianzhongists are just two sides of the same coin. While I don't think there's much need to "convince" others (the emphasis here is on the activist's own perceptions, not on arguing with the audience), this article will try to list some research materials that you can use to refute others. , can also be further studied.

The very distinction between violence and non-violence is wrong . But the debate is not surprising. Activists around the world have long debated which strategy is better suited to promoting resistance—destructive or peaceful. You are right, ethics is a bit off topic here, but the topic is important and worth including, and we can turn to the sociology of sports for evaluation.

There have been many research papers showing the effectiveness of disruptive protest tactics in recent decades (just to name a few: McAdam's classic 1983 , Biggs and Andrews 2015 , Shattuck's 2013 study , etc. wait).

On the other hand, there is also a growing body of research demonstrating the benefits of nonviolent protest strategies (e.g., Chenoweth and Stephan 2008 ).

This may seem like a contradiction, but only at first glance.

There are actually three categories of tactics

There are not two tactics, "violent" and "non-violent", but three.

Here you should know:

1. "Destructive tactics" - the concept itself includes both violent and non-violent methods, although many times people often do not distinguish between them. This includes any tactic that disrupts the normal functioning of an institution or disrupts the daily routine of society. For example, even without the use of violence, blocking streets with roadblocks can disrupt the daily routine of an institution or even a region (such as Spanish truckers blocking highways to protest rising gas prices , etc.).

2. Violent tactics can be considered an extreme form of destructive tactics.

3. Non-violent destructive tactics can be considered a mild form of destructive tactics.

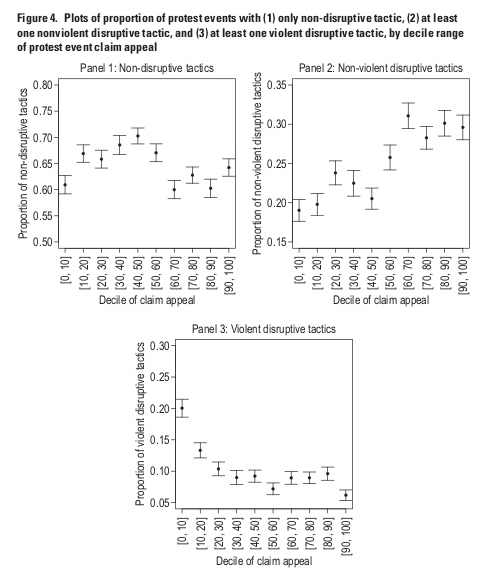

“The Use of Disruptive Tactics in Protest as a Trade-Off: The Role of Social Movement Claims ” by Wang and Piazza The study identified three categories of tactics: non-disruptive, non-violent disruptive and violently disruptive.

It is the result of a trade-off

Destructive tactics are more likely to attract the attention of the media, the public, and the government ( Amenta 2009 ; Snyder and Kelly 1977 ; Mueller and McClurg 1997 ; Tarrow 2011; Gamson 1975), more easily demonstrate the movement's determination (can influence the opponent's decision-making), and are able to Disrupting the functioning of certain parts of society to trigger associated transformations in customary social structures and routine practices ( Koopmans 2007 ; Sewell 1996 ).

But by using disruptive tactics, protesters may alienate grassroots support ( Feinberg, Willer and Kovacheff 2017 ; Haines 1984 ; Haines 1988; Elsbach and Sutton 1 992; Johnson, Dowd, and Ridgeway 2006 ), which is more likely to grow chances of movement success ( Ohlemacher 1996 ; Chenoweth and Stephan 2008 ; Meyer and Whittier 1994; Van Dyke and McCammon 2010; Heaney and Rojas 2014).

This means that when choosing tactics, protesters need to compromise on two fronts: on the one hand, taking advantage of the "political effectiveness rewards" provided by disruptive methods; on the other hand, trying not to lose support as much as possible.

Some papers show how this “tactical trade-off” emerges (eg Wang and Piazza 2016 ; Feinberg, Willer and Kovacheff 2017 ).

activist choice

The trade-offs between these tactics may depend on the following parameters:

1. The object of the protest - the government, enterprises, or non-state institutions. When protests target government institutions, the likelihood of using disruptive tactics becomes less overall, but the likelihood increases with the size of the protest ( Wang and Piazza 2016 ; Walker, Martin, and McCarthy 2008 ; Martin, McPhail, and McCarthy 2009 ).

2. When professional formal organizations join protests ( Wang and Piazza 2016 ; Kriesi et al. 1995; Meyer and Whittier 1994; McCammon 2003; Staggenborg 1988). When professional organizations enter a movement, they open access to greater resources, which makes publicly disruptive tactics such as marches and demonstrations less likely to be used (at least in countries with relatively open political opportunity structures) and instead Tend to negotiate.

3. The presence of police and counter-demonstrators at protests (different studies have mixed results).

4. The breadth of the protest agenda’s reach to different audiences ( Wang and Piazza 2016 ; Piven and Cloward 1977; Scott 1985; Van Dyke, Soule, and Taylor 2004; Tarrow 2011; Heaney and Rojas 2014; Jung, King, and Soule 2014 ; Grant and Wallace 1991; Jenkins and Eckert 1986)

Now let's just look at the last point above. Note that we do not now examine the ability of an agenda to mobilize support, but rather the process of broadening protest claims to a larger audience .

The following are the main conclusions of the study (summary only):

1. The more marginalized a protest group’s agenda is, the more likely it is to adopt destructive and violent tactics.

2. The broader a protest group’s agenda, the more likely it is to employ destructive, nonviolent tactics.

3. Non-destructive tactics are used at most protests and are almost independent of the scope of the agenda.

4. The anti-government focus of the protest or the presence of formal organizations at the protest moderates the positive relationship between the breadth of the protest agenda and the likelihood of using disruptive nonviolent tactics by increasing the likelihood of using nonviolent tactics. relation. The possibility of using destructive violent tactics remains associated with narrow protest demands.

5. During anti-government protests, the likelihood of using various types of disruptive nonviolent tactics drops sharply, while violent tactics are more likely to be used.

6. The most marginalized groups are most likely to resort to violence, but even a small increase in the breadth of the protest agenda they use will significantly reduce the likelihood of violence.

It appears that protest groups using agendas with the greatest reach will tend to use non-violent disruptive tactics (such as public marches to block roads) to increase the effectiveness of their protests, but avoid violent disruptive tactics (such as the occupation of key buildings by force ), as this could alienate existing and potential public support.

The article cites a very famous example. Employees at the Bay Area Metro system went on strike in July 2013 for pay increases. Four hundred thousand passengers lost the opportunity to use the service. However, the local community did not support the strike after it was discovered that workers' average wages were over $80,000 - much higher than the average wage in the area. It was felt that the inconvenience caused by the protests was too great for such a demand. Therefore, if the strategic goals of the protest do not justify the level of disruption required, then disruptive forms of protest will alienate potential support.

Nonviolence requires a balance

But the data above does not directly test the effectiveness of these solutions, it only shows which solutions are adopted more often. It can be assumed that when a protest agenda is widely accepted, the use of destructive nonviolent tactics will generally be the most effective solution. There are actually many studies that support this.

Nonviolent campaigns are better at attracting support ( Chenoweth and Stephan, 2008 ; Orazani and Leidner, 2019 ), are more likely to induce loyalty shifts among power brokers, officials, and businesses, and generally win more times than violent campaigns About twice as much ( Chenoweth and Stephan, 2008 ).

But that's not to say that nonviolent, destructive tactics are the universal answer. This trade-off is always determined by the specific strategic context and depends on the political environment and the capabilities of the protesters themselves. The choice between tactics is always flexible; it's more a matter of levels of destruction and violence than jumping between three options. Key words to remember: Protesters find a balance between pros and cons on different parameters to reach a strategic compromise.

If the value of one parameter is rigidly fixed (that is, the movement never gains or loses support no matter what we do) or redundant (say, nearly the entire population supports the movement), then the value of the other parameter Choice will be freer (i.e. more destructive tactics can be used without being "punished").

complex system

The above is a minimalist framework. Now let's add some details that may complicate the overall picture.

1. Expansion of protests and scale of protests

Research by Martin, McPhail, and McCarthy 2009 shows that the probability of violence increases with the size of the protest event; however, if we distinguish between the goals of the violence (violence against authorities, against civilians, against public or private property destruction) , you will find that while the probability of some types of violence increases, the probability of other types decreases. This may happen differently for different types of events and different collectives.

Here, it is interesting to point out the relationship between the size of the event and the likelihood of violence—one can see a contradiction with Wang and Piazza's findings. If the results of the above studies were allowed to be compared (to do so seriously and not in a conjectural way would require a large paper of its own), one might think that there might be differences between different types of tactics in sports Relatively complex trade-off dynamics: When protests expand their agenda, they tend to employ less disruptive tactics; large protests are more likely to involve some more disruptive tactics; but moderately disruptive (but not violent) movements do Attract more participants.

Perhaps a movement requires less disruptive tactics to gain and maintain support, but once a movement gains more support, it either allows for more disruptive tactics or may incentivize the use of these tactics. This in turn narrows the scope of support.

This suggestion echoes research on social relay, namely that a group that manages to create a more moderate image gains more support from the local community and is in fact able to use more extreme tactics ( Ohlemacher 1996 ).

Another study related to this hypothesis is also worthy of attention. Taking the anti-nuclear movement in the United States as an example, Jasper's 2004 study showed that when protesters expand their demands by forming strategic alliances , it brings more organizational resources to the protest movement, ultimately increasing the ability to use destructive protest tactics.

2. Dynamics of authoritarian countries

Paul Almeida provides a theoretical framework for understanding the dynamics of protest in authoritarian contexts. The liberalization of states stimulates the emergence and development of formal organizations within social movements that push movements toward less destructive forms of protest (“liberalization-stimulated mobilization”). But when the state tightens the screws again, civil society turns to more extreme forms of protest (“repression-inspired mobilization”), drawing on the organizational capital accumulated during the liberalization period.

3. Radical flanking effect

Researchers describe the radical flank effect: In some cases, groups that use extreme tactics and spread more extreme demands can contribute to the success of more moderate protests.

4. Fragmentation of the concept of violence: type, target, degree

Within the overall dynamics of the use of violence in protests, it is important to distinguish between strategic violence (violent tactics selected by activists based on strategic goals) and spontaneous violence (such as passive violent counterattacks—responses to repressors and counter-demonstrators). ). Different types may be more related to different aspects of the dynamics. Additionally, researchers distinguish between the target of violence (authorities, citizens, private property, public property) and the degree of violence (e.g., “nonviolent” tends to refer to relatively less violent movements).

5. Violence tendency

Violence does not always prevent public support. What matters is the nature of the violence. While violence by protesters can reduce public support, any violence against protesters can attract public support .

Some studies have shown that retaliatory violence by protesters, or violent backlash from repression ( Earl, Soule, and McCarthy 2003 ), may garner more support than violence initiated by protesters.

To theoretically interpret the new detailed data, more flexible concepts with greater "degrees of freedom" will be needed. To capture the mechanisms behind these subtle phenomena, Martin, McPhail, and McCarthy's 2009 study identified two parameters that can influence external audiences' perceptions of protest scale: disruptive potential and legitimacy. It can be understood as "moral capital".

Prejudice against violence

To sum up, the tendency towards violence has nothing to do with anarchist thought. It only reflects the status of a marginalized subculture. This is a classic situation: Frustration, social isolation, and lack of resources force a small group or individual to resort to tactics that produce noticeable "effects" without much investment in the short term, even though these tactics are likely to make things worse. No significant progress could be made.

Both the Tolstoyans and the Zhang Xianzhongs are just adding to the chaos. One misunderstanding of a situation becomes stronger when contrasted with another misunderstanding.

In a certain naive mind, the extreme, the eye-catching, the fast, seem more 'real'; the brief heuristics suggest the effectiveness of armed struggle.

But if we could start looking at "violence" strategically, we would get a very different picture.

Q: Can you recommend some introductory materials to people who know nothing about the resistance movement?

iyp : You can read this paper " Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment ". Framing processes should be seen as central dynamics in understanding the nature and processes of social movements, along with resource mobilization and political opportunity processes, the latter two of which have been much discussed in the case of China.

Framing can be seen as a struggle to produce ideas and meanings that mobilize and counter-mobilize.

Actors are not just bearers of meaning, but also create and sustain these meanings together with the media and authorities – a politics of symbols.

Just like a blank sheet of paper.

Q: I’m very lucky to have a blank slate. Such a simple tactic can quickly attract attention. Is it because there are too few large-scale protests in China? If so, you may not be so lucky next time. There seems to be a paradox. The more protests there are, the harder it is to attract people (commonly known as useless), and mobilization capabilities and effectiveness will decrease. How can I be more attractive? Are there any rules? Conversations are so difficult. To a certain extent, there is also a competitive relationship between dissent. They either refuse to comment to avoid quarrels, or they comment blindly just to quarrel. The value of communication is low. The moral rules established in some circles were originally designed to avoid quarrels, but the results were worse than nothing. I remember you wrote that "dissent does not understand love". To "love" on this issue is to be polite, which means that in-depth communication cannot be carried out. Is this contradictory?

iyp : There is definitely a pattern when it comes to attraction. But a blank piece of paper can’t be said to be “lucky”…

📱 Preview of the next episode’s topics:

The “Law of Attraction” of Movement and the “New Etiquette” of Opposition

🏴️

——To be continued——

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More