Kazuo Ishiguro: What is the future doing to us?

Recently, Nobel Prize winner Kazuo Ishiguro released his latest novel, and he has once again observed profoundly the fragility of our human beings in this technological age.

On a bright Saturday in late October 1983, nearly 250,000 people took to the streets of central London as the possibility of a nuclear war between the world's two superpowers grew. Among the crowd was a young author named Kazuo Ishiguro, who had just published his first novel. Ishiguro's mother survived the atomic bombing of Nagasaki in 1945, so his participation in the parade felt more personal. Together with like-minded friends, he chanted slogans demanding that the West give up its nuclear weapons and hope that the East would follow. On the way from Big Ben to Hyde Park, they waved signs and banners, and the crowd swelled with excitement. At the same time, there were opponents all over Europe, and for a brief moment it seemed like they could really change something. But Ishiguro had a problem: He worried that the whole thing would be a huge mistake.

In theory, unilateral abandonment of weapons is good, but in practice it can lead to catastrophic consequences. Perhaps the Soviet Union would respond as one had expected, but Ishiguro also had in mind a less peaceful outcome. Even though he recognizes the good intentions of the march, he fears that people will succumb to popular sentiment and go off track. His parents and grandparents had experienced the ebb and flow of fascism, and grew up hearing terrifying stories about the power of the masses. While Britain in the 1980s was very different from Japan in the 1930s, he recognized some common traits: tribalism, impatience with the nuances of distinction, and pressure to choose sides for the common man. As a gentle and prudent person, Kazuo Ishiguro did not want to realize at the end of his life that he had chosen the wrong career.

These anxieties found an outlet in the novel "The Painter of the Floating World", which he wrote at the time. The novel's narrator, Masuji Ono, is a man who waited too long to ask himself if he was supporting the wrong cause. As an aging painter living in Japan in the late 1940s, Ono suffered a moral scourge: his plethora of paintings glorifying Japanese imperialism, a source of glory and fame, became disgraceful in the postwar era. Looking back on his life, he tries to reconcile with his choices. Nietzsche once explained psychological repression so succinctly: "Memory says, you did so; but self-esteem replies, no, I can't. In the end, memory gives in." In Kazuo Ishiguro's novel, behind Ono's strong argument, The uphill battle of self-esteem and memory involved what he had been careful to hide from himself.

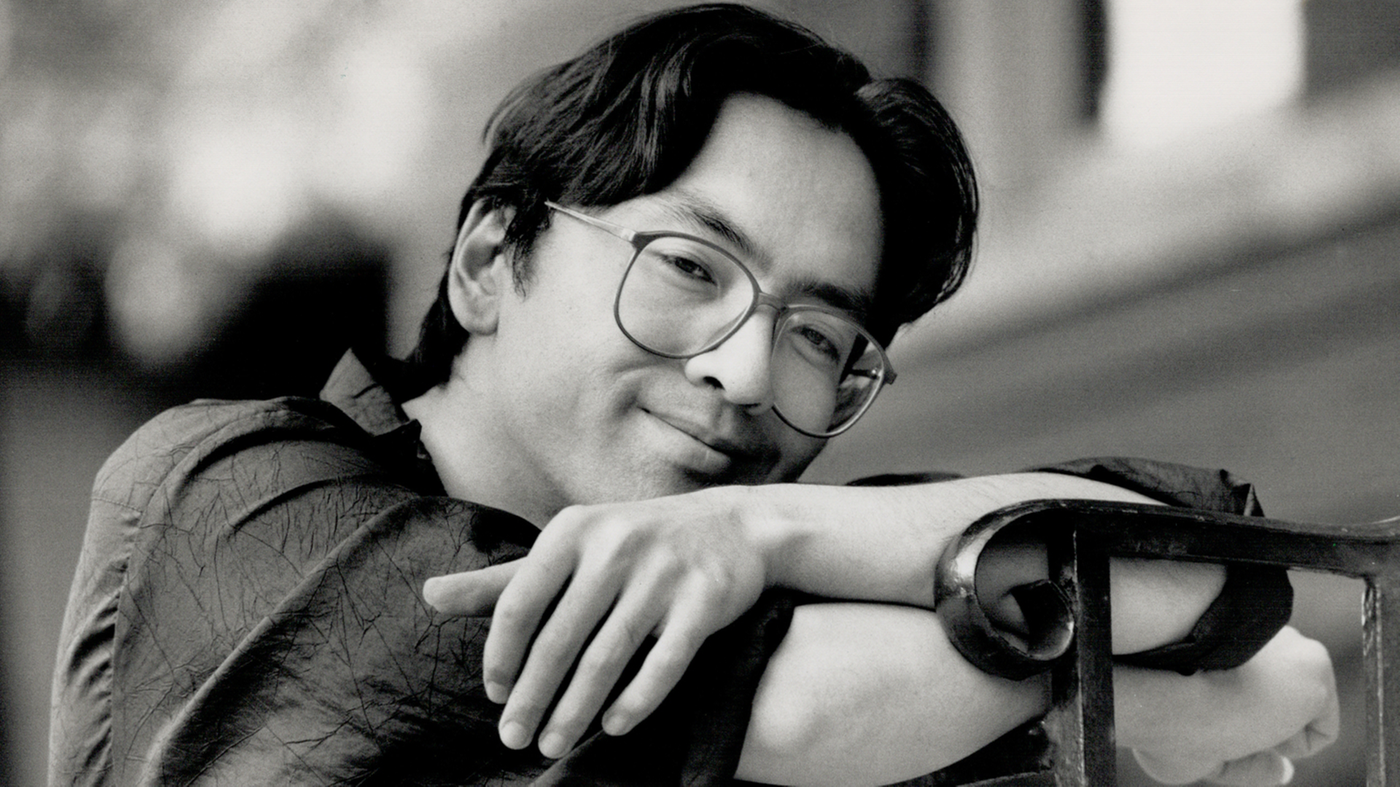

Now 66, Ishiguro is approaching the age of the shame-ridden protagonist he imagined in his youth. It would be an understatement to say he wasn't living the wrong life as he once feared - Kazuo Ishiguro, the master of subtlety, has been doing it for nearly 40 years. In 2017, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature — the highest recognition of its existence a writer can receive. In announcing the award, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences described: "Kazuo Ishiguro's novels, with their enormous emotional power, unearth the abyss hidden beneath our illusion of connection to the world". Whether it is Ono in "The Painter of the Floating World" or Stevens, the British housekeeper described in "Scar on the Long Day" (winning the Booker Prize in 1989), they are all people who have rarely known themselves. It wasn't until later in life that Stevens realized he had messed things up -- rejecting a beloved woman, wasting his best years, and serving a Nazi-sympathetic master between the two world wars.

Ishiguro had won numerous awards long before the Nobel Prize was announced, but the accolades never stopped him from asking the question that plagued him in 1983: "What if I'm wrong? What if I make a terrible mistake?" 2017 On the evening of December 7, 2009, he confessed to the audience of his award-winning speech that he began to wonder if he had built his novel's house on the beach. “I woke up lately and realized that I’ve been living in a bubble all these years,” he said from behind a gold-encrusted podium. “I realized that my world, with its humorous, liberal-minded people, is civilized and excited. The world of the human heart is actually much smaller than I imagined. The noise and dissatisfaction exposed by Brexit and Trump’s rise forced him to admit to a disturbing reality. “I grew up taking it for granted that liberal humanist values cannot be tolerated. Blocking," he said, "and that could be an illusion."

Kazuo Ishiguro's new book "Clara and the Sun" is his first work after winning the Nobel Prize, and more or less connects the questions he raised in his acceptance speech. The novel is set in a near-future America, where society is more divided than it is today, and the values of liberal humanism seem to be disappearing. And in the novel, our window to the world is no longer a human being, but a bionic robot powered by artificial intelligence. It's called Klara, or rather "her"—the choice of pronoun is key to the novel's morality. This book's shift in the categories of human self-perception raises a series of pressing but overlooked questions. If consciousness could one day be replicated in machines, would it still make sense to talk about a unique self, or would our own particularity, like a transistor radio, go the way of vanishing?

Unlike his awkward narrator, Ishiguro is a quirky, funny, self-deprecating man who feels comfortable using his talents. "If it weren't for the script I wrote, I think it would have been a pretty good movie," he told reporters recently, referring to "The Countess" (2005), a total failure by Photo by James Ivory and Ismail Merchant. The pair had better luck in the film adaptation of "Scars of the Day" (1994), which earned them an Oscar nomination for Best Picture. Maybe it's easier to be humble when everyone is talking about how amazing you are. Kazuo Ishiguro seems to get an average of one award a year, but there's something about him, a shimmering demeanor that makes you think he's going to be like this no matter what kind of sim you're in. Robert McCrum, his longtime friend and former editor, said: "There is no darkness in him. Or if there is, I haven't seen it."

His people were like this, so he wrote, and Kazuo Ishiguro's writing need not prove anything. The novels of his contemporaries, say Martin Amis or Salman Rushdie, can sometimes seem like a vehicle for brilliance, flamboyant prose and virtuosity It strikes the reader's face, but the beauty of the parts added together does not equal the beauty of the whole. Kazuo Ishiguro, on the other hand, is a self-effacing craftsman who takes the opposite of stunning. At first glance, his books will appear ordinary.

"It seems that the long-distance travel plan that has been lingering in my mind these days is more and more like it is really going to happen."

This is the first sentence of "Long Day Marks", and it's not amazing. The real work happens between the lines, or behind the lines, as Stevens defends his favorite sentimental romances: "They can strengthen one's mastery of the English language in a very effective way." As far as they can also provide fantasies for a distraught middle-aged bachelor, that's what the reader is left to infer. It is not without reason that Ishiguro lists Charlotte Bronte as his most influential novelist. From "Jane Eyre", he learned how to use the first person to write the story of a narrator who hides his feelings from himself, but can be seen by others. He reread "Jane Eyre" a few years ago, and when he saw some episodes, he would always think: oh my gosh, I'm just a parody of it!

Kazuo Ishiguro's new novel continues this salutary "stealing." The protagonist Clara is an AF (Artificial Friend), similar to a tutor, who is looking for a job. The first time we meet her (let's call her "her" for now) is in the window of a storefront, eagerly looking forward to meeting her future owner. Meanwhile, she had to adjust to street life. What's interesting about the novel's opening is seeing how Clara's new, synthetic consciousness gradually awakens. At first, she got to know things like space, color, light (AF uses solar power), but soon she started thinking about more esoteric realities, like the rigid caste system that shaped the society in which she was both The product of this and its witness.

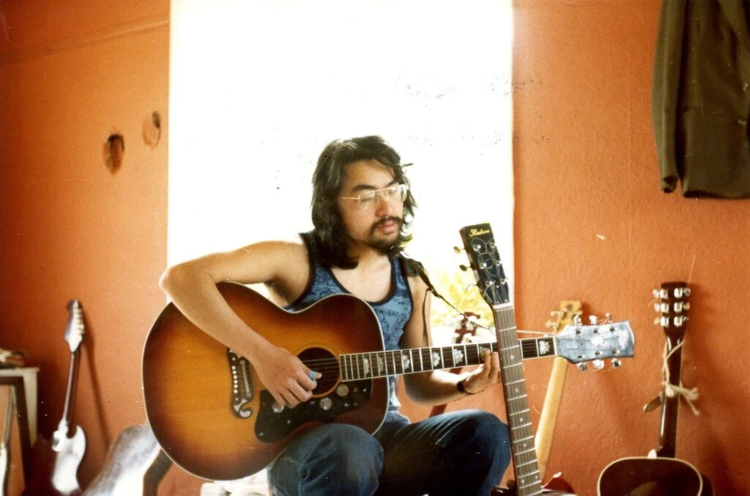

From a teenager to his early twenties, Kazuo Ishiguro also wanted to be a singer-songwriter. He had shoulder-length hair, a goatee, and was walking around in ripped jeans and colorful short sleeves. But now, the long hair and beard are gone, and he only wears black clothes (his daughter Naomi told reporters that he hates shopping, but wants to look good, so he bought a thousand black T-shirts directly) . He looked cool this interview night, dressed in black and rimless glasses, sitting in front of a monitor. There's a bookshelf to his right, full of Penguin Classics, and a bed of furry creatures crammed on his left (he's obliged because reporters want to see his room).

Ishiguro likes to compare their post-war generation to the character played by Buster Keaton in Captain II. In the film's classic scene, Buster Keaton is standing in front of a house whose exterior wall has been dumped on him, but an open window cuts right through him and saves him .

"We don't realize how lucky we are," Kazuo Ishiguro said in an appropriate, even tone. If we had been born earlier, we would have gone through wars and carnage -- all barbaric things." And they inherited a The incomparably comfortable material world, the culmination of the post-1960s sexual liberation movement, brought this world to maturity. "For my daughter's generation, it's not that safe," he said. "In the West, since the end of the Cold War, we have allowed massive inequality to grow, and as a result a considerable number of people think it may not be for us. "

Another theme of the story is technology that is always getting more complex. In "Clara and the Sun," the widespread use of artificial intelligence creates a permanently unemployed class, which in turn leads to mass revolt and top-down repression. Most contemporary stories about artificial intelligence, even well-written ones, such as Alex Garland's "Ex Machina" and Ian McEwan's "Machine Like Me", are about being a slave The cliché of the rise of robots to overthrow human domination. Kazuo Ishiguro's imagination was more realistic and more bleak. Clara and her ilk aren't fighting back, just letting governments and corporations control people more effectively.

On a philosophical level, AI also puts pressure on the traditional view that humans are special. As a character in the novel says, there is something unattainable within each of us that makes us what we are, however, this is just an illusion: human beings are just the sum of a series of biochemical processes. Kazuo Ishiguro said: "One of the assumptions of liberalism is that human beings have intrinsic value, and that value is not conditioned on a contribution to society, the economy, or some common cause. If we now, we can even be Reduced to a bunch of algorithms, then, it would seriously erode the idea that everyone is unique and therefore deserves respect and care, whether or not they can contribute to a common cause.”

Of course, Kazuo Ishiguro is a novelist, not a philosopher. The power of his book comes from bringing to light the dangers faced by people in this abstract proposition. The danger begins when Clara is picked out by a young man named Josie from a pile of AF in the store. Josie suffers from an unknown disease. At first, her family seemed like readers, not sure how to get along with Clara. To them, Clara is like something between an au pair and a home appliance. Ishiguro showed great sympathy in these contradictions. One second, Clara was delighted to see Josie confided in her like a sister, and the next, she rudely ordered her to leave the room. For a long time, Clara just stood in the corner with no regrets, waiting to serve everyone.

Great stylists such as Amis have rediscovered the physical world by defamiliarizing it, describing, for example, the steam rising from New York City's pavement fences as "a subway-smelling carnivore." But Kazuo Ishiguro is more complex and simpler: he will use fairly simple sentences to familiarize the human condition. The faces of the strange creatures distorted by pain that he saw time and time again in his works were originally a mirror. In "Forget Me to Go" (2005), which critic James Wood called "one of the central novels of our time," the narrator is a clone named Kathy H. At a young age, Kathy attended a prestigious British boarding school called Hailsham, where she and others like her received a solid liberal arts education while gradually realizing her true social role: serving as a non-clone organ donor. This involuntary affair begins shortly after graduation and does not end until the donor is "finished" (ie, dies), which is typically "finished" when they are in their early 30s.

Kathy knew what to expect, but she told her story and seemed to accept her fate without self-pity or panic. There’s an almost lingering sense of humor in the way she describes it all, as if state-sanctioned organ theft is just another little annoyance in life, like a tax return or a parking ticket. "Why don't they scream?" Readers wonder about these death camp prisoners. Their situation seems nightmarish, a sadistic abbreviated tragedy of life—until we realize that it differs from us only in the details, and sooner or later, we are all bound to our inevitable fate.

As a storyteller, Clara is much the same as Casey. As Josie becomes more and more emotionally invested in her new AF, it also reflects the emotional investment of readers. Over time in the book, the rift between "it" and "she" narrows. Whether this rift can, or should, disappear is a provocative open-ended question. However, Clara's experience with emotionally strenuous labor in an increasingly volatile job market has parallels with our own. Ishiguro says of his preference for narrators that seem outrageous: "You can put the reader down, and they'll suddenly realize that the person they've been reading is not so unfamiliar. I want them to realize: This is what We, this is me."

Like "Guernica" and "Chernobyl," the word "Nagasaki" is more a symbol of human destruction than an actual place name. For the young Ishiguro, however, it was just his hometown. When he was born in 1954, the city had been largely rebuilt, and no one was talking about war. He spent his early years in a three-generation home with tatami mats and shoji-mon, which is often featured in director Yasujiro Ozu's films, symbolizing a disappearing lifestyle. No washing machine, no TV. To watch his favorite show "The Lone Ranger," Kazuo Ishiguro had to stop by a friend's house next door.

Kazuo Ishiguro's father, Masao Ishiguro, was an oceanographer whose research on storm surges attracted the interest of the British government. In 1960, he moved his young family to the small market town of Guildford, an hour's drive from London, for short-term research work. Like Nagasaki, Guildford is a place with traditional customs. The narrow, winding paths are often clogged with cows, and milk is still delivered by horse-drawn carts. When the Ishiguro family arrived, it was Easter, and they were stunned by the horrific images they kept seeing around the town: a man crucified, blood spilling from his sides. Everyone there is white, even continental Europeans are a rarity. However, the newcomers were warmly received by the family. Ishiguro learned English quickly, and in school he learned to turn his foreignness to his advantage. For example, he said he was a judo expert. He also started going to church and became the head of the choir. His family believes it is important to respect local ways, no matter how outlandish they may seem.

The move to the UK was meant to be temporary, but Ishiguro's annual research funding has been extended, and his return to Japan has been delayed. Growing up between two cultures, Kazuo Ishiguro absorbs his surroundings with an almost ethnographic sense of alienation, while also constructing a mythical account of the distant homeland he left at age 5. image. From his mother Shizuko (a former teacher), he heard horrific scenes of life during the war: a man whose skin was completely burnt by an atomic bomb survived in a basin of water; from a moving train A bull's head was glimpsed in the window, but the rest of the bull's body was nowhere to be seen. The comics and books his grandparents sent regularly paint a more fascinating picture of Japan. For Ishiguro, being Japanese was a personal source of confidence, but the more deeply rooted he was in Britain, the harder it was to imagine how to go back. He was relieved in the late 1960s by his parents' decision to stay in the UK forever.

Unlike many future novelists, Ishiguro didn't inhale the classics heavily as a boy. He spends his time listening to and creating music. In 1968, he bought his first Bob Dylan album, "John Wesley Harding," and started backtracking from there. He and his friends would sit for hours, nodding to Dylan's obscure lyrics, as if they could understand every word. He told reporters that it was like a microcosm of adolescence, pretending to know but not knowing anything. Ishiguro isn't just bluffing, though. From Dylan, Leonard Cohen, and Joni Mitchell, he learned about the possibilities of the first person: how to conjure a character with just a few words.

Ishiguro's daughter Naomi is also about to publish her first novel, Common Ground. She told reporters that in all the characters written by her father, she did not recognize his shadow, and she later corrected her statement. Ono's playful grandson's obsession with "Popeye" and "Lone Ranger" in "The Painter of the Ukiyo" reveals a nascent American cultural hegemony, and it's likely that Ishiguro was like that at the time. Here, however, the similarity stops. Borrowing a concept from singer-songwriter Amanda Palmer, Naomi says: "Some people turn the mixer of art very low, so you can see where everything is coming from. Some people turn it very high, so you don't at all. I can't see it." Ishiguro's art mixer was on high. Like Colson Whitehead or Hilary Mantel, he's more likely to open up to people who are different from him.

Still, it’s tempting to draw a line between Ishiguro’s fragmented immigration experience and the outsider narrative angle he later pursued. Stevens in "The Long Mark" is the consummate English housekeeper, but as his new American boss points out, he's been imprisoned in a stately house for so long, with little chance of actually seeing England. On the advice of his employer, he travels to the western countryside, where he acts like a helpless foreign tourist, lost, out of gas, and completely incomprehensible to the locals. In fact, it is not the Brits that confuse Stevens, but ordinary humans. At the end of the book, Stevens watched the sunset on the pier by the sea, observing with interest a group of people gathered nearby:

"I first took it for granted that they were a bunch of friends going out on a good night. But after listening to their conversation for a while, it turned out that they were just a bunch of strangers who happened to meet in this place behind me. Apparently, They all stopped and watched for a while, waiting for the lanterns to come on, and then resumed their friendly chat. Now they were all laughing happily together under my watch. It's strange how people can interact with each other. A warm relationship is built up so quickly.”

Like Clara gazing out at the crowd from a storefront window, Stevens may be observing the aurora, always amazed by the commonplace.

Before studying English and philosophy at the University of Kent, Ishiguro hitchhiked around the United States, and upon his return he worked various jobs and even caught grouse for Queen Elizabeth at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. After about a mile of trenches, Queen Elizabeth and her guests sat and waited with shotguns, while grouse hunters would trudge through the heather trees in the moor, driving the birds within range. At the end of the season, Her Majesty will host a reception for the catchers. Kazuo Ishiguro was struck by her kindness, especially how she let them know it was time to leave: she didn't turn on the lights even though it was late, and as the sun began to set, she murmured: "Oh, It's getting dark" and then invites guests to see a series of paintings that happen to be placed in the corridor leading to the exit.

If the experience gave him a behind-the-scenes look at a grand old country house, his post-graduation job at an organisation helping the homeless find housing in west London gave him an insight into the other side of the social spectrum. one end of life. While working there, he met and married Lorna MacDougall, a social worker from Glasgow. MacDougall is Ishiguro's first and most important reader, and her comments are not stingy. After reading the first 80 pages of his last novel, "The Buried Giant" (2015), she told him that flashy dialogue simply didn't work and he needed to start over. Ishiguro did so.

He has always been open to feedback. In 1979, Kazuo Ishiguro applied to the University of East Anglia's creative writing course and was accepted. An old friend of his, Jim Green, who was doing an M.A. at the time, remembers Ishiguro's reaction to his weekly reading at a 19th-century fiction seminar. Green says: “I was impressed by the way he talked about Stendhal, Dickens, Eliot or Balzac as if they were like-minded. There was no sense of arrogance or exaggeration, but he treated them as creative writing Colleagues in class, they're showing him their work. Like, ah, well, that's how it happened, it's done that way, um, don't know if that's going to work."

Kazuo Ishiguro's first novel "The Shadow of the Far Mountains" started at the University of East Anglia. It is mainly based on the background of Japan in the mind. It is an imaginary story that he left at the age of 5 and never returned Home imitations. Like almost everything he's going to write later, it's an anxious self-justifying monologue, in which the narrator consistently says he doesn't feel the need to defend himself. Etsuko is a middle-aged Japanese woman living in the UK whose daughter recently committed suicide. From the beginning, readers expect some kind of awakening to tragedy in the characters, and instead, Etsuko goes on to talk about a woman she met in Nagasaki many years ago, and her mischievous daughter. Gradually, we begin to suspect that a narrative shift is taking place, in which Etsuko, numbed by grief, is transferring her uncontrollable feelings for her daughter to these characters from the past. Had it not been for the apparent success of this transfer experiment, the novel might have received the "experimental" label. The novel was published to universal acclaim in 1982, when Ishiguro was only 27 years old. The following spring, the literary magazine Granta placed him on a list of Britain's best young novelists, along with Salman Rushdie, Martin Amis and Ian McEwan. The magazine's recognition made him emboldened, and he decided to quit his job and devote himself to literary creation.

Ishiguro is not the kind of writer who listens to characters. He never sat at a desk improvising and suddenly started novels. He plans patiently and meticulously. Before he starts writing formally, he spends years in an open-ended dialogue with himself, noting the ins and outs of the tone, context, perspective, motivation, etc., of the world he wants to build. "Casey's self-deception is not about what happened in the past (like Ono, Stevens, etc.), but about what will happen," he wrote in a notebook for "Don't Let Me Go" in early 2001. Writing, clarifying the narrator's psychological profile, "Isn't it better not to let them live in a prison-like environment?" A few days later, he questions the clones: "Should they live in a wider community? Is there any other way for them to be controlled, to be labeled, to perform their duties? Maybe not: a prison they don’t know is a prison is the best.”

He didn't start writing detailed sentences and paragraphs until he had drawn a detailed blueprint for the entire novel. At this point, too, he follows a well-polished procedure. First, he writes very fast, and without having to stop and revise, he drafts a chapter in a desperate way. He would then read it through, breaking the text into numbered sections. Then, on a new piece of paper, he would make a sort of map of what he had just written, summarizing each numbered section of the draft in short bullet points. The purpose of this is to understand what the different parts are doing, how they relate to each other, and whether they need tweaking or more clarification. From this map, he would create a flowchart as the basis for a second, more laborious, careful draft. When the draft was completed to his satisfaction, he would finally put it in order. Then, he moves on to the next chapter and starts the process all over again.

Kazuo Ishiguro said that he is not obsessed with work at all. Some writers write with almost nothing else in mind, and he can write nothing for years without being bothered. "Clara and the Sun" is only his eighth novel. By comparison, his contemporaries Rushdie, Amis and McEwan on the Granta list have written 12, 15 and 16 books, respectively. When he's not writing, he enjoys having lunch with friends or playing his guitar to pass the day (he's been writing lyrics for famous American jazz singer Stacey Kent since the mid-2000s).

"You probably work harder than me," Ishiguro told reporters one evening in early December. He is sitting at his desk in his second home, a 17th-century limestone cottage in the Gloucestershire countryside, where he and his wife often spend weekends. During the epidemic, they had a post-package routine. Sitting at the kitchen table, MacDougall would read aloud the classic British crime tale "Serpents in Eden," while Ishiguro paced the dining area, as he put it, "like a cage. s cat". Wearing a black T-shirt over a black hoodie, Ishiguro said: "What sets the detectives apart is that they have this strange, mysterious perception of things like old English tapestries or Greek mythology. You know, that's often what makes them solve the puzzle."

Speaking of the lower number of works, Ishiguro said: "I have no regrets about that. I think, maybe I'm just not that dedicated to my career because writing wasn't my first career choice. It's almost a compromise. because I can't be a singer and a composer. Writing is not something I want to do every moment, it's something I'm allowed to do. So, when I write, I really want to write, and if I don't want to write Don't write anymore."

When he really wants to write, he can write directly. He sketched the first draft of "Long Day Marks" in four weeks, from morning to night, stopping only at mealtimes. At the time, the practice helped him as he and his wife needed a new advance. However, Ishiguro can't make it fast now. He was skeptical of the modern office and the need to always be on call. He said: “The way capitalist society is organized, the workplace is an alibi. If you want to avoid the difficult parts of your emotional life, you can just say, sorry, I have too much work to do right now. We are invited to disappear into professional commitments."

Kazuo Ishiguro started as a writer in the early 1980s, when market fundamentalism was sweeping across Britain and the West, a development that caught him completely by surprise. Speaking of his younger self, he said: "I never wanted revolution but did believe that we could move towards a more socialist world, a more generous welfare state. In my adult life , for a long time, believed that was the consensus. When I was 24, 25, I realised that Margaret Thatcher was starting to make a big difference in Britain.” Although his book never explicitly refers to Thatcher of neoliberalism, but reflects its frustrating consequences for people. For Ishiguro's characters, not working is not an option, or even a hobby. Stevens was so devoted to his duties as a housekeeper that he left his father's sick bed and went downstairs to serve guests. Clara is an upgraded version of Stevens. She doesn't need to sleep, she doesn't need to eat, and she doesn't even have any personal life.

When he told his audience in his Nobel lectures that he had been taking for granted the inexorable progress of humanist values, it was probably a part of humility. Indeed, the flaws of our current liberal order, and the selective blindness of its beneficiaries, are examined in his work. In "Don't Let Me Go," the clones hold up a mirror to the reader (like them, we're going to die one day), and while the same goes for the non-clone characters, these ordinary people calmly accept that mass slaughter of the same kind. How is this possible? We know that there was a public outcry following the horrific news about the conditions in which clones were raised, but no one wants to return to a world where the endless supply of organs has ceased, a world where cancer and heart disease remain incurable , so discussions of systemic change come to nothing. Instead, progressive boarding school Hailsham was established, a slightly progressive compromise that allows people to ease their guilt without substantially changing the status quo. The clones would still be bred to be Reaper, but some of them had the chance to read poetry and play art in a pleasant rural setting before getting the scalpel.

You don't need to be a Marxist revolutionary to see the parallels between Ishiguro's novel and the economic distribution of today's society. Over the past year, low-wage workers in retail, healthcare and other industries, many of whom depend on on-time paychecks, have faced a daily choice between going hungry or exposing themselves to the deadly virus middle. In "Don't Let Me Go," the clones are euphemistically referred to as "donors," a term that, for both clones and humans, belies the involuntary nature of their situation. In the US, the terms "essential worker" and "frontline hero" serve a similar purpose. Meanwhile, the nation's billionaires collectively saw their wealth rise by $1.1 trillion, up nearly 40 percent from the same period in March last year. Of course, the great plague did not reveal the inherent cruelty of the system, as some have claimed. Cruelty has always been apparent to those who choose to see it. It remains to be seen whether there will be transformative changes to the injustices that are visible today, or incremental compromises as always.

Perhaps the most chilling resonance of "Don't Let Me Go" is the lack of unity among the clones. Although their suffering is collective, they can only imagine individual forms of resistance. They don't strike, they don't resist, they don't even try to escape. They were simply pinning their hopes on a rumor that an "extension" might be granted to a few, the couples who could prove they were truly in love. In a powerful essay on the book, American philosopher Nancy Fraser argues that Ishiguro exposes the "double-edged sword" of individualism. The liberal arts-educated clones began to see themselves as unique, irreplaceable beings that Fraser called "a hallmark of personality and intrinsic worth." Outside of school, their only value is as body parts, but schooling has left them unprepared for this reality. Fraser believes that this process also exists in our society: "It is as individuals that we are exhorted to take responsibility for independent living, encouraged to satisfy our deepest desires through the purchase and possession of goods, and guided from the collective Action turns to personal solutions, the search for a precious, irreplaceable self.”

"Clara and the Sun" isn't Ishiguro's best novel (it has problems with Act III, and the image of Josie and her family is a bit odd and underwritten), but it offers a vision of what to do if we can't Beyond this restrictive view of freedom, where are we headed. What is most disturbing about the future it imagines is not that machines like Clara are becoming more and more human, but that humans are becoming more and more machines. We're slowly discovering (and friends hoping to avoid spoilers should now skip to the beginning of the next paragraph) that Josie's mysterious cause is a gene-editing operation to boost her IQ. The high-risk and potentially high-reward operation could make her a member of the professional super-elite. Those who gave up or simply couldn't afford surgery essentially made themselves financial serfs.

Human plasticity has been a pressing concern for novelists for hundreds of years. Ishiguro told reporters that he had always admired 19th-century writers like Dostoevsky. They were writing at a time when ancient religious beliefs were being called into question by the rise of the theory of evolution. At that moment, he said, it seemed natural to ask the question that in modern times was a harbinger: Does the human soul exist? If it doesn't exist, how will it affect our understanding of the meaning of human life?

"I grew up in a time when you didn't really ask questions like that, but in my opinion, huge breakthroughs in science and technology forced us to go back to these questions and ask, what is an individual?" Ishiguro said.

This is the question Ishiguro has been asking in his own way since he first started writing. Judging by the poor and docile people in his books, his vision of people seems vague. In "Don't Let Me Go," Kathy's friend Ruth says during a debate about "possibles" (referring to real people who may be clone models): "We're based on trash. If you want to find them , if you really find it, you should go to the people in the gutter. Go to the trash can, go to the toilet, and you will find out where we came from." Of course, this is where most of Ishiguro's characters go. , whether human or not. That's how they end up once society has taken from them everything that can be exploited.

But the strange thing is that when we come out of his book, we don't feel the cheapness and nothingness of life, on the contrary. In "Don't Let Me Go," Casey's job is as a "caretaker," where a clone starts to donate organs and will take care of their people. Her patients include her old classmates Ruth and Tommy, who were once a couple. Casey and Tommy have been attracted to each other since childhood, but reality always separates them. Later in the novel, they finally got together and had a short-lived happiness. Believing they were eligible for an extension, they tracked down one of their old teachers, only to be told the extension was just a myth. Soon, Tommy died, and Kathy got word that it was time for her to donate her organs.

While she cherishes the memories with old friends, Kathy says she doesn't dwell on the past: "The only time I've indulged in my life was driving to Norfolk a few weeks after hearing that Tommy had passed away. "This is where the three of them have been together. On a quiet country road, she noticed a barbed wire fence and a cluster of trees on the edge of a field, filled with rubbish. "It's like the trash you see on the beach, and the wind must have blown the trash for miles before it hit these trees, and these two rows of barbed wire." The sight recalls Ruth's words earlier in the book. "We made it out of trash models," but Kathy's reflections on what she saw offer a defiant contrast, like a light dirge for the neglected and outcast:

"That was the only time. I was standing there, looking at the strange garbage, feeling the wind blowing from the field, and started having a little fantasy...I was thinking about the garbage, on the branches Flying plastic, strange things on the coast caught in barbed wire, I half-closed my eyes, imagining this is where everything I lost as a child was washed ashore, I'm standing here now, if the wait is long enough, a The little figure would appear on the horizon across the field, and it would grow bigger until I could see it was Tommy, and then he waved and maybe called my name."

"I think it's an optimistic view of human nature," Kazuo Ishiguro said of "Don't Let Me Go" on a recent episode of BBC Radio 4's "Book Club". Love and friendship may not Escaping death, but they will grow stronger and deeper until the very end. In his view, this tenderness, not the exploitation of clones, is the moral center of the novel.

What exactly is an individual? First of all, we are all unfinished and make mistakes big and small. Technology holds the promise of human perfection, but in Kazuo Ishiguro's view, this is a promise we must resist. The mistakes we make are the keys to discovery.

Almost from the moment he started writing, Kazuo Ishiguro had only tasted success. The reporters last spoke to him in mid-January, wondering what the main disappointment of his remarkable career would be.

“They’re like parallel lives,” he says, separating his public self, who gives interviews and awards, from his private self, who spends his days in his study trying to bring an imaginary world to life: “Most of the time , After I finish writing a book, I always have a feeling that I haven't fully written down what I want to write. This may be the reason why I keep writing. I always feel a sense of urgency to go back to my desk, because I never I don't feel like I've written what I wanted to write."

When we discussed the topic of artistic failure and frustration, his line of thinking led him to an old memory. The summer after high school, he and a group of musician friends lived for a few weeks in a cabin near Loch Fyne on Scotland's west coast. With their instruments and a portable recorder, they recorded songs day and night. Ishiguro had an idea to re-arrange his all-time favorite song "By the Time I Get to Phoenix," written by Jimmy Webb and made famous by Glen Campbell. He recalls: "I literally tricked my friends into making myself miserable, asking them to be this and that, one of us, not me, of course, who happened to be a super good guitarist, and a The individual is a very talented singer, and it all happened." Later, the song was almost exactly what he envisioned.

"The thing that was in my head, the abstraction, became reality, right there," he continued, narrowing his eyes and lowering his voice, "it was very, very close to what I always wanted to achieve, remember there was a kind of Strange high emotions." Ishiguro chuckled to himself, recalling a long-lost summer: "At the time, I thought this kind of moment would come up often, but in retrospect, I never felt that way again. already."

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More