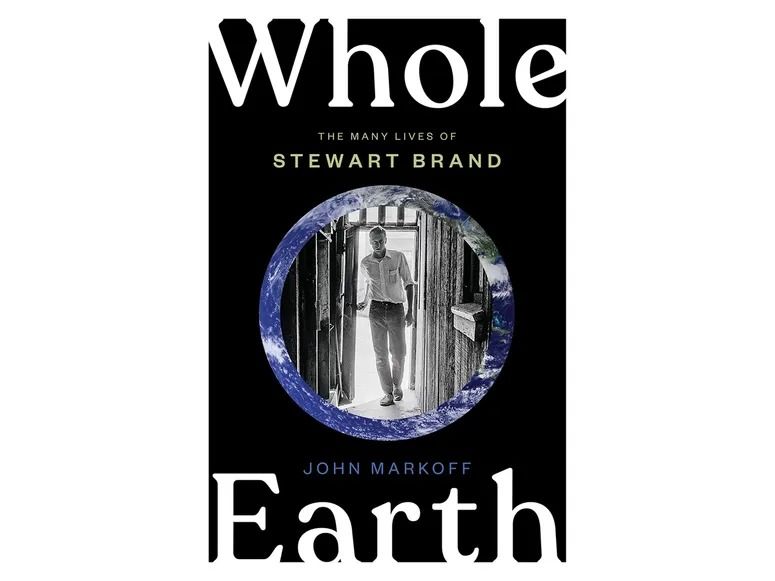

Biography Whole Earth: A Look Back at Stewart Brand's Planetary Impact

John Markoff, a Pulitzer Prize winner who has covered Silicon Valley since 1977, knew Stewart Brand in the early 1980s. He chronicles Brand's life story in his recently published book Whole Earth: the Many Lives of Stewart Brand. This biography is the result of John Markoff's years of going through Brand's personal diaries and letters, many of which are in the special collections of the Stanford University Libraries at Brand's alma mater, as well as in Brand's alma mater. Lots of interviews with him in the Bay Area office.

Recently, http://slowdown.tv interviewed John Markoff about Stewart Brand's trajectory and guiding principles, as well as his early days on emerging trends and social movements The uncanny ability to get into it, sometimes even of his own making.

http://slowdown.tv : Articulating Stewart Brand's philosophy and work can seem like a daunting task. What do you think is his greatest achievement? What is the impact of these achievements on society and the planet?

John Markoff: In the 1960s and 1970s, Brand was an inspiring role model for a generation trying to break down the social boundaries of middle-class America. The Whole Earth Catalog is not only a guide to creating your own life, but its spirit was captured by Steve Jobs in 2005, when he told Stanford graduates: , "Stay hungry. Stay foolish" (Stay hungry. Stay foolish). He was quoting Brand. The Whole Earth Catalog is an engine of serendipity — as you read it, you discover interesting ideas, and your whole life moves toward an orthogonality based on what you stumble upon direction of development. This idea, this set of ideas, comes from the same force that created Silicon Valley.

Brand's latest organization is the Long Now Foundation, which aims to advance our culture in a long-term direction. It is too early to tell whether the effort will have a significant impact. But they are building a clock that can run for 10,000 years, a time span they call "the long now" to make their point.

http://slowdown.tv : Stewart Brand's efforts revolve around seemingly disparate themes - environmentalism and technology. Can you elaborate, for him, how they relate to each other?

John Markoff: The subtitle of the Whole Earth Catalog is "Access to Tools," which is important. The opening line in the introduction to the first issue of the Whole Earth Catalog is also legendary: "We are as gods and might as well get good at it" . If you asked Stewart Brand today how that quote came about, he would tell you that the inspiration came from Buckminster Fuller. His takeaway from Fuller was that if you give a person a tool and teach them how to use it, they can use it to change the world, and the introduction in the catalog captures that vision.

The PC fits this, it's a universal tool. Stewart Brand was also influenced by [engineer and internet pioneer] Douglas Engelbart, who introduced him to the idea that computers would be tools that humans could use to guide society.

http://slowdown.tv : Do you think it was these core focuses that helped him predict the future so accurately?

John Markoff: Stewart Brand always had ideas early on. He often hears about something that will be a significant force, and in many cases he is actually a factor in its creation. He was a member of a group called "Merry Pranksters" around writer Ken Kesey. He also participated in a series of parties known as "Acid Tests", culminating in one of the largest Acid Tests organized in January 1966.

After his discharge from the military in 1962, Stewart Brand wanted to be a photojournalist at one point. His first paid job came from the architects who founded the Stanford Student Union, who gave him the assignment to photograph buildings. When he was on campus, he was shown the computer center, which at the time had a big central computer with a graphics display. He saw two young people playing a video game - which was actually the first video game - "Spacewar!" and was impressed that both were out of their bodies while playing experience. What he saw was what we now call cyberspace, or the metaverse. He didn't write about the experience for the next decade, but when he wrote an article for Rolling Stone in 1972 ( SPACEWAR - by Stewart Brand ), it was a truly groundbreaking one . He came up with all the ideas that would be the way we use computers now, long before the personal computer industry. In fact, Stewart Brand coined the term "personal computing" in a book he later wrote [II Cybernetic Frontiers].

Another example is when he started thinking about why there are no pictures of the whole Earth. Stewart Brand started a movement: he ended up wearing billboards and selling badges on four college campuses [that read "Why haven't we seen an image of the entire Earth?" 't we seen an image of the whole Earth yet?)]. He sent badges to all members of the U.S. Congress, even to those in the Kremlin. After that, NASA released a photo, which had a huge cultural impact. The iconic image of the 50s was the (nuclear) mushroom cloud. It was a very dark vision of the future, but it changed. NASA images were used by Earth Day and the environmental movement that formed in the early 1970s. Stewart Brand really played a role in this.

http://slowdown.tv : What makes Stewart Brand's ideas so influential and timeless? What inspired the way he thought about the world?

John Markoff: To understand the threads that drove Stewart Brand's activities, you have to understand that at age 8, he accepted Outdoor Life magazine's commitment to conservation : "As an American, I pledge to save and faithfully defend our nation's natural resources—soils, minerals, forests, waters, and wildlife—from waste." (I give my pledge as an American to save and faithfully to defend from waste the natural resources of my country—its soil and minerals, its forests, waters, and wildlife.) He can still recite this phrase today, which is the basis of all his planning, thinking, and writing.

http://slowdown.tv : What was the most surprising thing you learned about Stewart Brand while writing the book? Or, what aspects of him might the reader be surprised by?

John Markoff: While researching his biography, the biggest surprise for me was a "disappearance" diary he made during 1967, 18 years after he donated it to Stanford University , which he gave me in 2018. The diary chronicles a failed project he worked on that year (1967) to try to create an "Education Fair" at the San Mateo County Fairgrounds. The project failed because he failed to raise funds for it.

In his diaries, however, I found something that made me rethink his role in Silicon Valley. He came to Menlo Park to "let his technology happen," he wrote in August 1967. That's special in itself. Many of his friends were leaving the city, "back to the land", to establish communes. Brand went in the opposite direction and somehow ended up in the heart of Silicon Valley, which was becoming the high-tech hub it is today.

I also discovered that he was much more influenced than I realized by computer scientist Douglas Engelbart, whom I mentioned earlier. Engelbart invented the computer mouse, hypertext, and many of the ideas that underlie modern computing. The conclusion is that it is wrong to view the Whole Earth Catalog in the context of the Back to the Land movement. Rather, it grew out of the same forces that shaped Silicon Valley, and it represents Silicon Valley’s early influence on American culture — an independent and entrepreneurial sensibility that would later become a hallmark of the region.

http://slowdown.tv : In the book, you notice that Stewart Brand has always had a strong commitment to science, but some of his views have changed considerably over time, Such as those driving the Whole Earth Catalog. How do you feel about these shifts, and how did these shifts affect his thinking?

John Markoff: You can't easily categorize him. Stewart Brand, who calls himself a conservative, refuses to read The Wall Street Journal because he hates their opinion pages. What kind of conservative is this? He wrote a book in 2009 called Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto, in which he broke with the environmental movement. He changed his mind on several technologies opposed by the environmental movement, notably genetically modified food and nuclear power.

He did change his mind about things over time. However, there are a few things that remain constant about Brand. Human responsibility for the environment has been a primary point of view throughout his life. (The responsibility humans have for their environment has been an overarching viewpoint of his throughout his entire life.)

Original: A New Biography Looks Back on Stewart Brand's Planetary Impact

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!