Breaking the cycle of triumph and despair -- David Graeber: The Shock of Victory

David Graber's unexpected death surprised everyone. Just days before, anarchist groups were communicating with him about Facebook's decision to ban anarchist pages to appease the Trump administration. David Graeber, one of the first to issue a statement, charged: "As you can imagine, there is nothing like telling us - especially our young people - that we are forbidden to dream of a peaceful, caring world. more violent behavior."

This fits David's character. He wasn't just an intellectual, he was always eager to take a stand and put himself at the forefront of things . He participated in the Direct Action Network in New York City, which sparked the massive demonstrations against the Ministerial Conference of the Free Trade Area of the Americas in Quebec City in April 2001, the culmination of the "anti-globalization" movement; he was also the founder of "" A key player in the Occupy Wall Street movement, and involved in the ensuing debate on "violence," faced the same self-righteous pedants as other anarchists. When Rojava's revolutionary experiment was threatened by the Islamic State, he was one of the first to direct international attention to the experiment and joined the anarchist group in calling for solidarity when Turkey invaded a year earlier.

- In case you missed Those of Us 99%: Thinking About New Political Identities on the 10th Anniversary of Occupy Wall Street

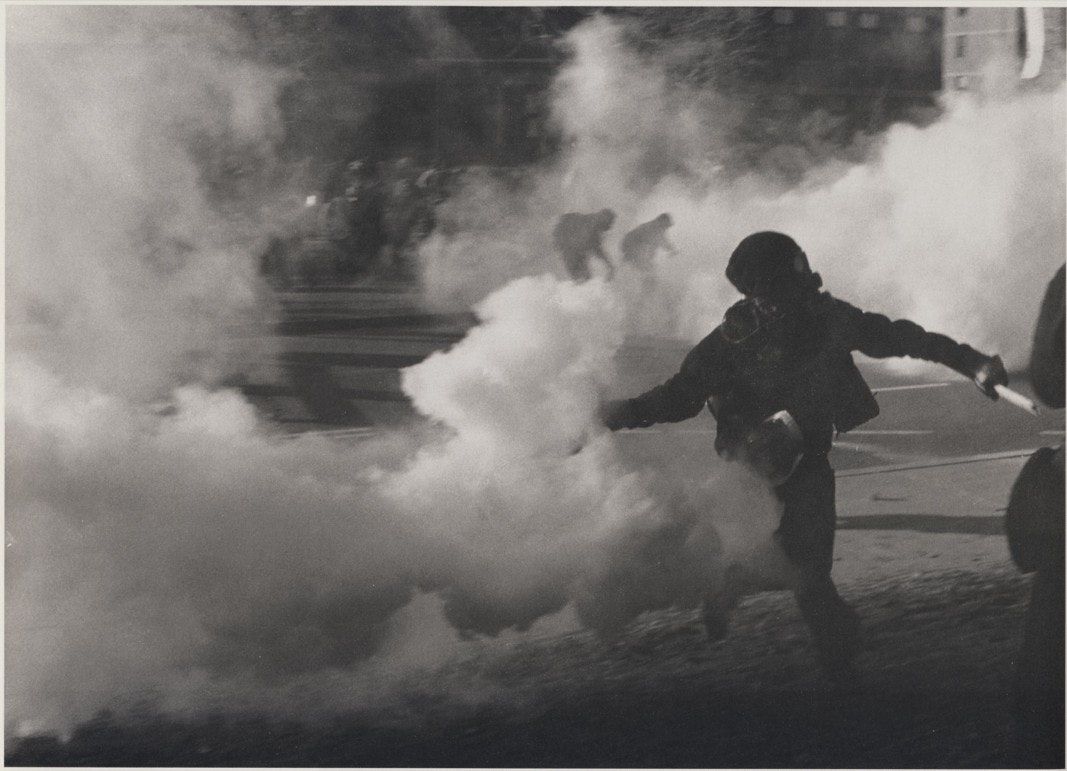

He put his body and his reputation on the front lines of the battle, risking tear gas and academic reprisals. After Yale forced him to leave because of his political beliefs, David was forced to move overseas to find a university position commensurate with his abilities. He got a corporate publishing contract, yes, but he got it by refusing to compromise, not by downplaying his political beliefs.

David wrote, thought, said, and did so much more than we can summarize here. Hopefully others will be able to write a proper eulogy for him as well, documenting all his activities and contributions in various fields. Even in our disagreements, we can all always learn from him. He was a staunch friend and a worthy opponent.

Among Graeber's most detached works, such as " If we can't have fun, what's the point?" , where he grapples with fundamental ontological questions about freedom and the universe. Such is our impression of him, weaving together disparate threads to come up with a vision of self-determination that extends from subatomic particles to whole societies and ecosystems.

He died at the age of 59. We sincerely thank everyone who remembers him. We mourn his passing and grieve for all that David has yet to share with us.

The article to be shared below comes from a discussion of the legacy of the turn-of-the-century anti-capitalist struggle, emerging amid protests against the World Trade Organization, the World Bank, and proposed “free” trade initiatives such as the Free Trade Area of the Americas. Anarchists and other anti-capitalist protesters played a major role in delegitimizing the WTO and the World Bank, and even succeeded in blocking the passage of the Free Trade Area of the Americas agreement—yet after the fact, many participants in the movement Frustrated that we have not succeeded in completely abolishing capitalism.

Following this discussion, David expanded on his ideas in the Rolling Thunder article, which resulted in the following article, The Shock of Victory.

David's argument that anarchists are often unprepared for victory is more timely today than it was in early 2008. Over the past few years, anarchists and other proponents of abolishing the police, prisons and the existing criminal justice system have succeeded in popularizing the notion that all of these are unjust institutions that do not govern our lives legality. Unsurprisingly, authoritarians and the police have attacked this with great violence.

In a war of attrition involving nighttime clashes, it's easy for demonstrators to feel "we're losing" -- and on a historical level, we've achieved goals that seemed unimaginable just a few years ago. Whether it's 2008 or today, the question is the same - how do we strategize on a long enough time horizon to make the most of our victories, rather than collapse in the face of the desperate blow of a counterattack.

Fix your eyes forward on what you can do, not back on what you cannot change. - Tom Clancy

Below is the article.

The biggest problem with the direct action movement is that we don't know what to do with victory.

This may seem like an odd thing, since many of us haven't felt particularly victorious lately. Today, most anarchists view the global justice movement as a blip: certainly inspiring while it lasts, but not a movement that has succeeded in laying lasting organizational roots or changing the contours of power in the world. The anti-war movement was even more frustrating because anarchists and anarchist tactics were largely marginalized. Sure, wars end, but only because wars always have a beginning and an end. No one felt that they contributed much to the end of the war.

I would like to propose another explanation. Three preliminary points are made here:

1. As strange as it may seem, the ruling class does live in fear of us. They still seem to be haunted by the possibility that if ordinary people really knew what the ruling class was doing, those in power might all be hanged from trees. I know this seems unbelievable, but it's hard to think of other explanations as to why, as soon as there is any sign of massive mobilization, especially direct action on a massive scale, the ruling class goes into panic mode and usually tries to start some kind of war to divert public attention.

2. To a certain extent, however, this panic of the ruling class is justified. Mass direct action - especially when organized along democratic lines - can be very effective. There have only been two such large-scale actions in the United States in the past three decades: the anti-nuclear movement in the late 1970s, and the so-called "anti-globalization" movement from 1999 to 2001. In each case, the movement's main political goals were achieved far faster than nearly all participants imagined.

3. The real problem with this type of movement is that participants are always taken aback by the speed at which they initially succeed. We were never ready for victory. It throws us into chaos. We started fighting each other. With some new mobilization for war, the intensification of repression, and the agitation for nationalism, inevitably fell into the hands of dictators on every side of the political spectrum. As a result, when the full impact of our initial victory becomes clear, we are often so busy feeling as losers that we don't even notice that victory is coming.

Let me introduce the two most prominent examples one by one.

I: Anti-Nuclear Movement

The anti-nuclear movement of the late 1970s marked the first appearance in North America of what we now consider standard anarchist tactics and organizational forms: mass action , intimate groups , voice committees, consensus processes, prison solidarity, decentralized principles of direct democracy… Compared to now, it's all a bit primitive and there are major differences - especially the stricter Gandhi-esque concept of non-violence , but all the elements are there, and this is the first time they've come together as a whole.

For two years, the movement has grown at breakneck speed and is showing signs of becoming a national phenomenon. Then, almost as quickly, it disintegrated.

It all started in 1974, when some veteran pacifists in New England successfully blocked the construction of a proposed nuclear power plant in Montague, Massachusetts. In 1976, they joined other New England activists to form the Clamshell Coalition , inspired by Germany's year-long factory occupation.

The immediate goal of the Clamshell Alliance is to block the construction of a proposed nuclear power plant in Seabrook, New Hampshire. While the coalition ultimately did not carry out the occupation, and instead endured a series of dramatic mass arrests , coupled with prison solidarity, their operation — with tens of thousands at its peak organized along lines of direct democracy — led to The idea of nuclear power has been successfully challenged in unprecedented ways .

Since then, similar alliances have sprung up across the country: Palmetto Alliance in South Carolina, Oystershell in Maryland, Sunflower in Kansas, and most famously, the Abalone Alliance in California (Abalone Alliance); The Abalone Alliance initially opposed the utterly insane plan to build a nuclear power plant on Diablo Canyon - which is almost exactly on a major geographic fault line.

The Clamshell Alliance achieved great success with its first three large-scale operations in 1976 and 1977. But it quickly plunged into crisis over democratic process problems.

In May 1978, the newly formed Coordination Committee violated procedure by accepting a last-minute proposal by the government to hold a three-day legal rally in Seabrook instead of a planned fourth occupation (with the excuse of unwillingness). distance from surrounding communities). Debates about consensus and community relations started and then expanded to issues of the role of nonviolence (even cutting fences, or defensive measures such as gas masks, were initially banned), gender bias, and so on.

By 1979, the coalition had split into two contentious factions, and with increasing inefficiency , the Seabrook nuclear plant (or half of it) became operational after many delays.

The Abalone Coalition lasted longer until 1985, in part because of its strong anarchist-feminist core, but eventually the Abloh Canyon project they resisted was also licensed and became operational in December 1988.

On the surface, that doesn't sound too exciting. But what is this movement really trying to achieve? Here, it might be helpful to paint a picture of what it's all about:

1. Short-term goal : Prevent the construction of specific nuclear power plants (Seabrook, Diablo Canyon…).

2. Mid-term goals : To stop the construction of all new nuclear power plants, to delegitimize the concept of nuclear power, and to begin a shift towards environmentally friendly and green energy sources, and to legitimize new forms of direct democracy inspired by nonviolent resistance and feminism.

3. Long-term goals : (at least for more activists) to overthrow the state and destroy capitalism .

If so, the results are clear. Short-term goals are almost never met. Despite many tactical victories (delays, utility bankruptcies, legal injunctions), the factories that became the focus of mass action eventually came online. The government simply does not allow itself to be seen as having lost such a battle.

Long-term goals are clearly not achieved either. But one reason it wasn't achieved was that the mid-term goals were almost immediately achieved. These actions did delegitimize the idea of nuclear power -- raising public awareness so much that the industry was forever doomed when the Three Mile Island meltdown occurred in 1979.

[Note: Snowden's whistleblower uses the same strategic model and also achieves mid-term goals, see " 6 Years, What's Changed?" ”; but the barriers to long-term goals must be understood and reflected upon, see Beyond the Transparency Revolution . 】

While the Seabrook and Diablo Canyon plans may not have been canceled, nearly all other nuclear reactor construction plans that were pending at the time were, and no new plans have been proposed for a quarter of a century. There is indeed a process towards the legitimacy of eco-friendly, green electricity and new democratic organizing technologies. All of this happened much faster than anyone could really expect.

Looking back, it's easy to see that most of the subsequent problems arose directly from the movement's rapid success. Activists had hoped to connect the nuclear industry to the nature of the capitalist system that created it. It turns out that when the nuclear industry becomes a burden, the capitalist system is more willing to abandon it. Once giant utilities start claiming that they too want to promote green energy, effectively inviting what we now call NGOs to sit down at the negotiating table, there is a huge temptation to drop the fight. Especially since many of them are simply allying with more radical groups in order to earn a place for themselves in the first place.

The inevitable result is a series of heated strategic debates. But it is impossible to understand this without first understanding that strategic debates rarely take place in direct democracy movements—they almost always take the form of diversionary debates. Take the problem of capitalism, for example. Anti-capitalists are generally more than happy to discuss their position on the issue; on the other hand, liberals really don't like to say "actually, I'm in favor of maintaining capitalism", so whenever possible, liberals Will try to change the subject.

So the debate about whether to challenge capitalism directly usually ends up being red-faced, as if it were a short-term debate about tactics and nonviolence. Authoritarian socialists or others who are skeptical of democracy itself also don't like to make this an issue, preferring to discuss the need for the broadest possible coalition. Those who do like democracy, but feel that a group is taking the wrong strategic direction, often find it far more effective to challenge its decision-making process than to question its actual decision-making.

There's another factor that's less mentioned here, but I think it's just as important. Everyone knows that in the face of a broad, potentially revolutionary coalition, the first move of any government is to try to divide it — making small concessions to appease moderates while selectively criminalizing radicals. This is the Art of Governance 101.

In addition, the US government has a global empire that is constantly being mobilized for war, giving it another option that most governments don't have. Those running the U.S. government can at any time increase the level of violence abroad ; this has proven to be a very effective way to defuse social movements built around domestic issues. The civil rights movement was followed by major political concessions and the rapid escalation of the Vietnam War, the anti-nuclear movement was followed by the abandonment of nuclear power and the intensification of the Cold War, and global war plans and proxy wars in Afghanistan and Central America, the global justice movement was followed by the Washington Consensus Disintegration and the war on terror, it seems no coincidence. As a result, the early SDS had to put aside its early emphasis on participatory democracy and become a mere anti-war movement; the anti-nuclear movement evolved into a nuclear freeze movement; the horizontal joint structure of DAN and PGA gave way to ANSWER and UFPJ Such a top-down mass organization.

From a government perspective, a military solution does have its risks. As in Vietnam, the whole thing could blow up in front of people (hence, at least since the first Gulf War, the ruling class was obsessed with designing a war that would effectively prevent domestic protests). There is also a small risk that some miscalculation could accidentally trigger a nuclear armageddon that would destroy the planet. But these are risks that politicians in the face of civil unrest seem to be more willing to take—as the direct democracy movement does frighten the ruling class, and the anti-war movement is their preferred opponent.

After all, the state is fundamentally a form of violence - violence is the mother tongue of the state. Once the debate shifts to violence versus nonviolence, the ruling class returns to its home ground, where they can best justify and enforce their actions.

Organizations, whether designed for waging war or against war, tend to be more hierarchical than those designed for almost anything else. This is of course also the case with the anti-nuclear movement.

While the anti-war mobilizations of the 1980s far outnumbered those of the Clamshell Coalition or the Abalone Coalition, they also meant a return to banner-carrying marches, permitted rallies, and abandonment of experiments in new forms of direct democracy .

II: Global Justice Movement

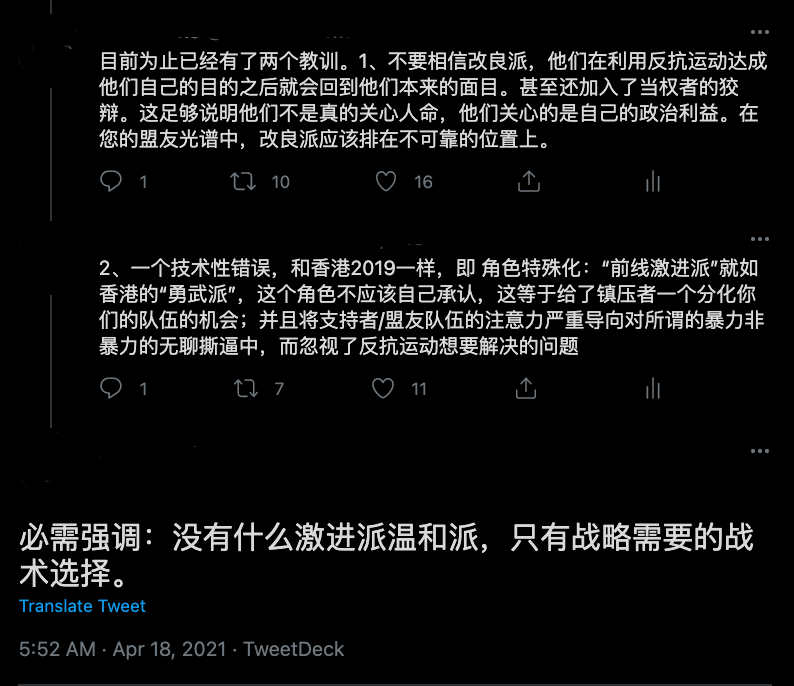

I think our moderate readers are generally familiar with the actions at the World Trade Organization meeting in Seattle, and events like the April 16 IMF and World Bank blockade that erupted in Washington six months later, and so on.

In the United States, the movement has exploded so quickly and so dramatically that not even the media can deny it entirely. However, it also quickly began to dissolve itself. Direct Action Networks are established in nearly every major city in the United States, and while some (notably Seattle and Los Angeles DAN) are reformers, anti-corporate, and enthusiasts of strict nonviolent norms, most (such as New York) and Chicago DAN) are largely anarchist and anti-capitalist and committed to tactical diversity. Other cities (Montreal, Washington D.C.) created more explicitly anarchist anti-capitalist aggregates. Anti-corporate direct action networks disbanded almost immediately, rarely lasting more than a few years. There are endless heated debates: about violence and non-violence, about shifting fronts, about issues of racism and privilege, about the viability of an online model.

Then came 9/11, followed by a massive increase in repression and the paranoia that followed, and the panic flight of almost all of our former allies in trade unions and NGOs. By Miami in 2003, we seemed to be overwhelmed, a paralysis that engulfed the movement, and we had only recently begun to recover.

9/11 was such a bizarre event, such a disaster, that it made it almost impossible for us to perceive anything else around us. In the aftermath of the event, almost all the structures established in the globalization movement collapsed. But one reason they collapse so easily—and not just because the question of war is so imminent—is that, again, most of our immediate goals have been achieved unexpectedly.

In my case, I joined the NYC Direct Action Network around A16. At the time, the Direct Action Network as a whole saw itself as a group with two main strategic goals: One was to help coordinate the North American part of the vast global movement against neoliberalism and what was then called the Washington Consensus, to destroy neoliberal ideas. Hegemony, blocking all new big trade agreements (WTO, FTAA), discrediting and eventually destroying organizations like the IMF; another is replacing the old fashioned way of organizing activists and their steering committees and ideological squabbles, spreading a (very much) Anarchism-inspired) Direct Democracy Model - Decentralized, Intimate Team Structured, Consensus Process.

At the time we occasionally called it "contaminationism," arguing that people just needed to be exposed to the experience of direct action and direct democracy, and they would want to start imitating it themselves.

It is widely believed that we are not trying to create a permanent structure; the direct action network is just a means to that end. Several founding members explained to me that when it served its purpose, it was no longer needed. On the other hand, these are pretty ambitious goals, so we also think that even if we do achieve them, it will probably take at least a decade.

As a result, it only took about a year and a half.

Clearly, we have failed to spark a social revolution. But one of the reasons we never got to the point where we inspired hundreds of thousands of people to revolt is because we achieved other goals so quickly. Take organizational problems, for example. While the Anti-War Coalition still operates as a top-down popular front group, as the Anti-War Coalition has always done, almost every small militant group not dominated by some sort of Marxist sect (this includes Syrian immigrants from Montreal Organizations like Community Gardens in Detroit) are now largely operating on anarchist principles, though they may not know it themselves. Infectionism works. Also, take the field of ideas as an example. The Washington Consensus is in ruins. So much so that it's hard to remember what the country's public discourse looked like before Seattle.

The media and the political class rarely agree on anything so completely - "free trade", "free markets" and unrestricted hypercapitalism are the only possible direction of human history; the only possible solution to all problems The plan is so thoroughly presupposed that anyone who doubts the proposition is dismissed as a lunatic. Global justice activists, when they first forced themselves into the sights of CNN or Newsweek, were immediately described as reactionary lunatics. And a year or two later, both CNN and Newsweek said we won the debate.

Usually, when I raise this point in person with a group of anarchists, someone immediately retorts: "Yes, the rhetoric has changed, but the policy remains the same". In a sense it does. In other words, we did not destroy capitalism. But we ("we" here refers to a group of people who insist on horizontalism and direct action in the global anti-neoliberal movement) have, in just two years, given it a greater weight than any other action since the Russian Revolution. blow.

- If You Missed This Thing Without 'Revolutionary Government': Why You Can't Use the State to Abolish Class

Let me explain point by point.

1. Free Trade Agreements - Since 1998, all ambitious free trade agreements have failed. The Multilateral Investment Agreement (MAI) has collapsed; the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (FTTA), the focus of movements in Quebec City and Miami, has stalled. And most of us only remember that the 2003 Free Trade Area of the Americas summit introduced the “Miami model” of extreme police repression of apparently nonviolent civil resistance .

That's true, but we forget that this kind of measure is first and foremost the struggle of a group of furious losers - the Miami meeting was where the AAFTA finally fell. No one even talks about such a broad and ambitious treaty anymore. The United States can only strive for smaller state-to-state trade agreements with traditional allies such as South Korea and Peru, or use the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) to unite the rest of its Central American dependents, and it is not even clear whether it will succeed .

2. The World Trade Organization - their organizers moved their next meeting to Doha in the Persian Gulf after the disaster in Seattle, apparently deciding they would rather risk being blown up by bin Laden than go through it again A blockade of a direct action network. For six years, they have insisted on the "Doha round".

But the problem is that, fueled by the protest movement, governments in the Global South have begun to refuse to open up imports of agricultural products from rich countries, unless those rich countries at least stop spending billions of dollars in subsidies for their own agriculture, so that farmers in the Global South can’t may compete with it. The U.S. in particular was not going to make any of the sacrifices it asked other countries to make, so all deals fell through. In July 2006, WTO President Pierre Lamy announced that the Doha Round negotiations would no longer be held, and no one would mention the next WTO negotiations for at least two years after that. Most likely no longer exists.

3. On the IMF and World Bank side - this story is the most amazing. The International Monetary Fund is rapidly heading for bankruptcy as a direct result of the worldwide mobilization against it. To put it bluntly: we destroyed it. The World Bank is no better there. But when we feel the full effect of the mobilization campaign, we don't even notice it.

The last story deserves to be told in detail.

The International Monetary Fund has been the main adversary in this fight. It is the most powerful, arrogant, and ruthless tool that has been used for the past 25 years to impose neoliberal policies on the poorer countries of the Global South (by manipulating debt).

In exchange for emergency refinancing, the IMF has asked these countries to adopt “structural adjustment programs” that force massive cuts in health and education spending, food price maintenance, and endless private ownership schemes that allow foreign capitalists to buy local resources cheaply. ization plan.

For some reason, these structural adjustments never recovered those countries' economies, which meant they were still in crisis, and the solution always insisted on another round of structural adjustment.

The IMF has another, less well-known identity: the global enforcer. Their job is to ensure that no country (no matter how poor) can default on loans to Western bankers (no matter how stupid). Even if a banker made a $1 billion loan to a corrupt dictator who deposited the loan directly into his own Swiss bank account and fled his country, the IMF would have to ensure that $1 billion (plus lucrative interest) from his former victims.

If a country defaults on its debt for any reason, the International Monetary Fund imposes a credit boycott with an economic impact roughly equivalent to a nuclear bomb. This all runs counter to basic economic theory, according to which lenders should take a certain level of risk; but in the world of international politics, economic law is used only to restrain the poor.

This role of global enforcer led to their downfall.

What happened next was that Argentina defaulted on its debt and got away with it. In the 1990s, Argentina was the IMF's top student in Latin America - they privatized almost all public facilities except customs. In 2002, the Spanish economy collapsed. We all know the immediate consequences of the collapse: street fights, mass rallies, the overthrow of three governments in a month, road blockades, occupation of factories. Lateralism—essentially the principle of anarchism—is at the heart of popular resistance. The political elite is so untrustworthy that politicians have to wear wigs and fake beards to eat at restaurants without being physically attacked. When the moderate Social Democrat Nestor Kirchner came to power in 2003, he knew he had to do something dramatic to get most people to accept even the idea of a government, let alone a government Accept his government. So he did. In fact, he did something no president of any country was supposed to do—he defaulted on Argentina's foreign debt.

Kirchner is actually quite clever in this regard. He did not default on the loan to the International Monetary Fund. He defaulted on Argentina's private debt, announcing that he would pay only 25 cents for every dollar of all outstanding loans. Citibank and Chase Bank, of course, went to the IMF, and they habitually acted as enforcers, demanding that Argentina be punished. But for the first time ever, the IMF backed off.

First, because Argentina's economy is already in ruins, dropping an economic nuclear bomb will only throw a few rubble. Second, almost everyone knows that it was the disastrous IMF recommendations that set the stage for Argentina's collapse in the first place. Finally, and most decisively, is the enormous influence of the global justice movement: the International Monetary Fund is already the most hated institution on the planet, and wantonly destroying what little remains of the Argentine middle class will Push things too far.

So Argentina was let go. After that everything changed. Brazil and Argentina have jointly arranged to repay outstanding debts to the IMF. With a little help from Chavez, the rest of South America has followed suit.

In 2003, Latin America's debt to the International Monetary Fund was $49 billion; now it is $694 million, a drop of 98.6 percent. For every thousand dollars owed in Latin America four years ago, only fourteen dollars are now owed. Asia followed suit. Neither China nor India is now indebted to the International Monetary Fund and has refused to accept new loans. The boycott of the IMF now includes South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and almost every other important regional economy, as well as Russia. The group has fallen to the point of commanding only African economies, and perhaps parts of the Middle East and the former Soviet Union (basically oil-free). As a result, its revenue plummeted 80% in four years.

The irony is that the IMF is increasingly likely to go bankrupt if it can't find anyone willing to bail it out, and no one seems particularly keen to bail it out. With the IMF's reputation as a fiscal enforcer discredited, it no longer serves any obvious goals, even those of capitalists. At the recent G8 meeting, there were proposals to create a new mission for the organization — perhaps similar to the International Bankruptcy Court — but for a variety of reasons, all failed. Even if the IMF survives, it's just an empty shell.

The World Bank, which was a good cop in the beginning, is in slightly better shape now, but only "slightly" better. Its revenue, for example, fell by only 60% instead of 80%, and there was little actual resistance. On the other hand, the organization is still alive today mainly because some countries are still willing to deal with it, and both sides are aware of this, so the World Bank can no longer call the shots.

Obviously, all this does not mean that all the monsters have been killed. In Latin America, neoliberalism may still be at work, Europe's social protection systems are under attack, and much of Africa - despite the rather hypocritical representations of Bonos and the world's wealthy nations - remains deeply in debt among. America's economic power is in decline in much of the world, and it is desperately trying to tighten its grip on Mexico and Central America.

We do not live in a utopia. We already know this. But the question is why we never notice our victories.

Olivier de Marcellus, an activist for People's Global Action from Switzerland, points to one reason: whenever an element of the capitalist system, be it the nuclear industry or the International Monetary Fund, is Shock, and some left-wing magazines will start explaining to us why, saying it's all part of their plan - or maybe the result of the inexorable workings of internal contradictions in capital, but certainly not at all of our own making. Perhaps more importantly, we don't even want to use the word "us." Isn't Argentina's default on its debts planned by Nestor Kirchner? What does he have to do with the globalization movement? I mean, his hand was not forced by the thousands of citizens who rose up in rebellion, smashed banks, and replaced the government with popular rallies coordinated by the Independent Media Centre (IMC). Or, well, maybe it is. But even so, the citizens who resisted are people of color in the Global South, and how can "we" claim responsibility for their actions? Although most of them think they belong to the same global justice movement as we do, believe in similar ideas, wear similar clothes, use similar tactics, and in many cases even belong to the same alliance or organization as we do. Here, claiming "we" implies the original sin of speaking for others.

Personally, I think it is reasonable for a global movement to look at its achievements from a global perspective. These achievements are not insignificant. However, like the anti-nuclear movement, they are almost all focused on medium-term goals. Let me outline a hierarchy of similar goals:

1) Short-term goals: Block and shut down specific summits (IMF, WTO, G8, etc.).

2) Mid-term goals: destroy the "Washington Consensus" on neoliberalism, block all new trade agreements, undermine the legitimacy and eventual closure of institutions like the WTO, IMF, and World Bank; spread the idea of direct democracy new mode.

3) Long-term goal: (at least for the more radical members) to overthrow the state and destroy capitalism.

Here again we find the same pattern. Short-term tactical goals were barely achieved after the Seattle miracle. But that's mainly because when the government confronts such a movement, it tends to hold its own, arguing that it shouldn't be clearly defeated in principle. This is often seen as more important than the success of the summit itself. What most activists don't seem to realize is that often - take the 2001, 2002 IMF and World Bank conferences for example - the police crackdown that ends up being so cumbersome, they almost shut down the conferences themselves Many events are destined to be canceled, ceremonies ruined, and no one gets a chance to really interact with each other. But for the ruling class, the question is not whether trade officials can meet, but not allowing protesters to be seen as winners.

Here too, the rapid achievement of medium-term goals makes it more difficult to achieve long-term goals. Allies such as NGOs and trade unions "jumped" almost immediately; strategic debates ensued, but they always unfolded indirectly as disputes about race, privilege, tactics, etc., without mentioning the actual strategic battle. The country's resort to war also made everything extremely difficult.

As I've mentioned before, it's hard for anarchists to claim how much influence they had on the inevitable outcome of the Iraq war, or even on the setbacks the Empire had already suffered there, but there may be indirect effects. Following the catastrophe of the 1960s and the Vietnam War, the government did not abandon its policy of responding to the domestic threat of direct democratic mass mobilization by returning to war. But it has to be done more carefully. Most importantly, they had to design foreign wars to fend off domestic protests. There is good reason to believe that the first Gulf War was indeed designed with this in mind. The way the invasion of Iraq — insisting on using small, high-tech troops, relying heavily on indiscriminate firepower, and even targeting civilians to prevent U.S. military casualties from reaching levels similar to those seen in the Vietnam War — seems to be designed to deter any potential domestic Peace movement, not for military effectiveness . In any case, this perception helps explain why the world's most powerful military ends up being trapped, or even defeated, by an almost unimaginable mob of guerrillas with little access to the outer safe zone and no access to External funding, military support. As at the trade summit, the administration is so obsessed with ensuring that civilian resistance is not seen as the winner of a domestic struggle that they would rather lose the real war.

Perspective: Looking Back at Spain in the 1930s

So, how to deal with the shock of victory? I can't claim to have an easy answer. I'm actually writing this article more to start a conversation, to bring issues to the table -- to spark a debate about strategy.

However, some hidden meanings are more obvious. The next time we plan a large-scale operation, it is best to at least consider the possibility that perhaps our medium-term strategic goals will soon be achieved, and when that happens, many of our allies will withdraw. We must recognize what strategic debates actually are, even if they appear to be discussing other things .

Take a famous example: the debate over property damage after the Seattle incident. I think most of these discussions are actually about capitalism. Those who denounced smashed windows do so mainly because they want to call on middle-class consumers to turn to green consumerism in a global exchange model, to ally with labor bureaucrats and social democracies abroad. This path is not intended to be a direct confrontation with capitalism, and most of us who urge us to take it are at least skeptical about the possibility of capitalism being truly defeated.

And those who break windows don't care if they offend suburban homeowners because they don't see them as potential members of the revolutionary anti-capitalist coalition. In effect, they wanted to hijack the media to send a message that the system was fragile - hoping to inspire a similar rebellion among those who might consider joining a real revolutionary coalition: teenagers who were out of touch with society, the oppressed of people of color, ordinary workers impatient with union bureaucracy, the homeless, the convicted, the deeply disaffected.

If a radical anti-capitalist movement is to start in America, it has to start with people who don't need to be convinced that the system is corrupt, they just need to know what they can do . In any case, even if it were possible to have an anti-capitalist revolution without gun battles in the streets (which most of us hope for, because let's face it, we're going to lose if we're crushed by the military) we can't be in Anti-capitalist revolution with strict respect for property rights.

The latter actually raises an interesting question. What does it mean to win? What does it mean to achieve not only our medium-term goals, but also our long-term goals? At present, no one even knows how this can happen, because we don't believe much in the capital "revolution" in the traditional sense of the 19th and 20th centuries. After all, the general idea of a revolution, that there will be a mass rebellion or a general strike, and then all the walls will fall, is entirely premised on the old fantasy of seizing state power. Only on this premise can victory be so absolute and complete (if we are talking about revolutions in whole countries or key territories).

Think about it, for example: if Spanish anarchists really "won" in 1937, what exactly would that mean? Surprisingly, we rarely ask ourselves such questions. We just imagine that it will start in a similar way as the Russian Revolution, then the old army is disbanded and workers' soviets are created spontaneously. But that's in a big city. The Russian Revolution was followed by years of civil war in which the Red Army gradually imposed control of the new state on every part of the old Russian Empire, whether those communities wanted it or not. Let's imagine if the Spanish anarchist militias routed the fascist army, disbanded it completely, and drove the government of the socialist republic out of its offices in Barcelona and Madrid, then by anyone's standards this must be victory. But what happens next? Will they make Spain a "non-republic", "anti-state" within the old international borders? Will they impose the system of popular assemblies on every village and city in the former Spanish territory? How to do it?

We must remember that in many villages, towns, and even entire regions of Spain at that time, anarchists were almost non-existent. In some areas almost the entire population is conservative Catholics or monarchists; in others (such as the Basque Country) there is a militant, well-organized working class, but mostly socialists or communists . Even at the height of revolutionary enthusiasm, most of these people remained true to their old values and ideals. If the winning Informal Anarchist Alliance (FAI) tries to exterminate them all - which will require killing millions - either deport them, or forcibly transfer them to anarchist communities, or send them to re-education Battalion - so that they would not only commit world-class atrocities, but also have to give up their anarchist stance. Democracy simply cannot be so methodical in its tyranny: doing so requires fascist top-down organization because you can't have thousands of people methodically slaughtering helpless women, children and the elderly and destroying communities , or drive a family out of their ancestral home, unless they can at least excuse themselves by saying that they are "just following orders." There seem to be only two possible solutions to this problem"

1. Let the republic continue to exist as a de facto government, controlled by the socialists; let them rule in the areas where the right wing is the majority, and at the same time make some kind of agreement with them to let the anarchist majority cities, towns and villages Organize as you want...and hope the government will stick to the protocol.

2. Announce that everyone will form their own local people's assembly and let them each decide their own self-organization model.

The latter seems to be more in line with anarchist principles, but the results won't be much different. After all, if the residents of Bilbao collectively decide to create a local government, who can stop them? Autonomous regions where most people remain loyal to the church or local landowners, presumably put the same old right-wing authorities in power; left-wing autonomous regions will put left-wing bureaucrats in power. Nationalists on the left and right will each form competing alliances, and will each declare themselves the legitimate government of Spain, even though they will only control a small portion of the former Spanish territory. Foreign governments would recognize one of these - because none of them would be willing to exchange ambassadors with a non-government like the Anarchist League, even if the Anarchist League wanted to exchange ambassadors with them (actually they wouldn't) .

In other words, the real gunfight may end, but the political fight will continue - much of Spain may look like the contemporary state of Chiapas, with every region or community divided into anarchist and anti-anarchy faction. Achieving the ultimate victory will be a long, difficult process. The only way to truly win a statist enclave is to convince their children that this can be achieved by creating a significantly freer, more pleasant, more beautiful, safe, relaxed, fulfilling life in stateless areas. On the other hand, foreign capitalist powers, even without military intervention, will do everything possible to thwart the notorious "threat of a good example" through economic boycott and subversion, as well as infusion of resources into statist regions. Ultimately, everything may depend on the extent to which anarchist victories in Spain can spark similar rebellions elsewhere.

The real point of this imaginative exercise is to point out that there has been no clean break in history. Implicit in the traditional notion of a "one size fits all" (the moment the state falls and capitalism is defeated) is that it is not a real victory if it is not done. If capitalism is still there, if it starts to sell your once subversive ideas, it shows that the capitalists really won, and you lost, you were codified. This statement seems absurd to me . Can you say that feminism has failed and achieved nothing just because corporate culture feels obligated to verbally condemn sexism and capitalist companies start marketing feminist books, movies and other products? Of course not: unless you have managed to destroy capitalism and patriarchy in one fell swoop, these phenomena are one of the clearest signs that you have done something.

Presumably all effective revolutionary paths involve numerous cooperations, victorious demonstrations, minor acts of rebellion or brief, covert moments of self-government. I dare not guess what it will look like. But to move in that direction, the first thing we have to do is recognize that we do win some.

In fact, we've won quite a few recently. The question is how to break the cycle of triumph and despair and come up with some strategic vision (the more the merrier) about how victories can reinforce each other to form a cumulative movement towards a new society.

We can make concessions, we can take a break, but we can't give up .

⚪️

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More