Trial Translation / Cultural Anxiety of Xenotransplantation

This article is translated from The Cultural Anxieties of Xenotransplantation by Gideon Lasco, published in Sapiens on February 15, 2022.

Original / Gideon Lasco

Translation/statement

The translation is for study and exchange only. Criticism and guidance are welcome. Please indicate the source when reprinting.

In early January, BBC News reported that David Bennett Sr., a 57-year-old man with severe heart disease, had received a genetically modified pig heart. The eight-hour operation in Baltimore, Maryland, was a great success.

Medical scientists cheered the operation . Human-to-human heart transplants have been a rare, expensive, and complicated procedure due to the scarcity of organs and the difficulty of matching organs between donors and recipients. Although thousands of people have the potential to benefit from this procedure , especially those with advanced heart failure, very few are able to receive a new heart. Those in the acceptable group must face the risk of rejection by the immune system.

The use of genetically modified pig organs could potentially pave the way for these life-saving treatments to become more widely available -- not only for those who need a heart, but also for those who need other organs. In the United States alone, more than 106,000 people are on the national transplant waiting list.

But many people around the world are uncomfortable with it. There were a lot of reactions to Bennett's new pig heart, surprise, curiosity, and conversation. The New York Times quoted a patient saying: "Then I'll make a sound like a pig?"

This ambivalence is consistent with the findings of popular psychological research on cross-species organ transplantation, or what we call xenotransplantation. For example, a Swedish study in the 1990s noted that 77% of respondents preferred organs from living human donors; 69% preferred organs donated by deceased humans; 63% preferred artificial Organs; only 40% prefer non-human animal organs. Although these attitudes are slowly changing, there are still many people around the world who are skeptical about organ transplantation or are morally opposed to organ transplantation, especially between animals and humans.

What is the reason for this?

Anthropologists and sociologists who study the ethical dilemmas of experimental medicine can help explain why xenotransplantation still worries many.

For example, researchers have linked people's "disgust" for receiving animal organs to widely held cultural beliefs about certain animals, that is, they consider certain species, such as pigs, to be unclean, Not suitable for sharing the same living space with humans. Especially in Islamic and Jewish contexts, pigs are not only considered unclean, but also forbidden as food. Given these taboos, some researchers speculate that " the wider Muslim community is less likely to urgently accept the use of pig organs for human transplants, even if human life is at stake. " Other religious scholars and pundits argue that if this saves people's lives life, then this treatment is reasonable .

In addition to recent ethical concerns about animal treatment, these sentiments include what medical sociologist Gill Haddow has described as "a generalized aversion to xenotransplantation."

Further complicating the “moral rethinking” of organ transplantation is that some people have unexpected understandings and experiences of organs, whether they come from humans or non-humans. For example, while from a biomedical perspective an organ is devoid of emotion, memory, and personality, many people feel otherwise as found in the ethnography of organ transplantation. According to anthropologist Lesley Sharp , organ recipients "often express the emotion that, by accepting a donor's organ, they can thereby gain access to the donor's emotional, moral, or physical characteristics."

Compared to other organs, performing a heart transplant may be particularly conflicting with the Western world's concept of the body, as the heart is traditionally considered the seat of the soul and personality (in contrast, in Asian societies such as the Philippines , the liver is traditionally considered to have a similar status). The idea that parts of a person may remain in their organs after they die has dominated the popular imagination, as can be seen in the popularity of books like A Change of Heart . The book tells the story of a woman whose personality changes after receiving a heart and lung transplant from a young man who died in a motorcycle accident.

With such a complex and varied understanding of organ transplantation, it's not hard to understand that some people have concerns about whether a pig's heart could affect the human body.

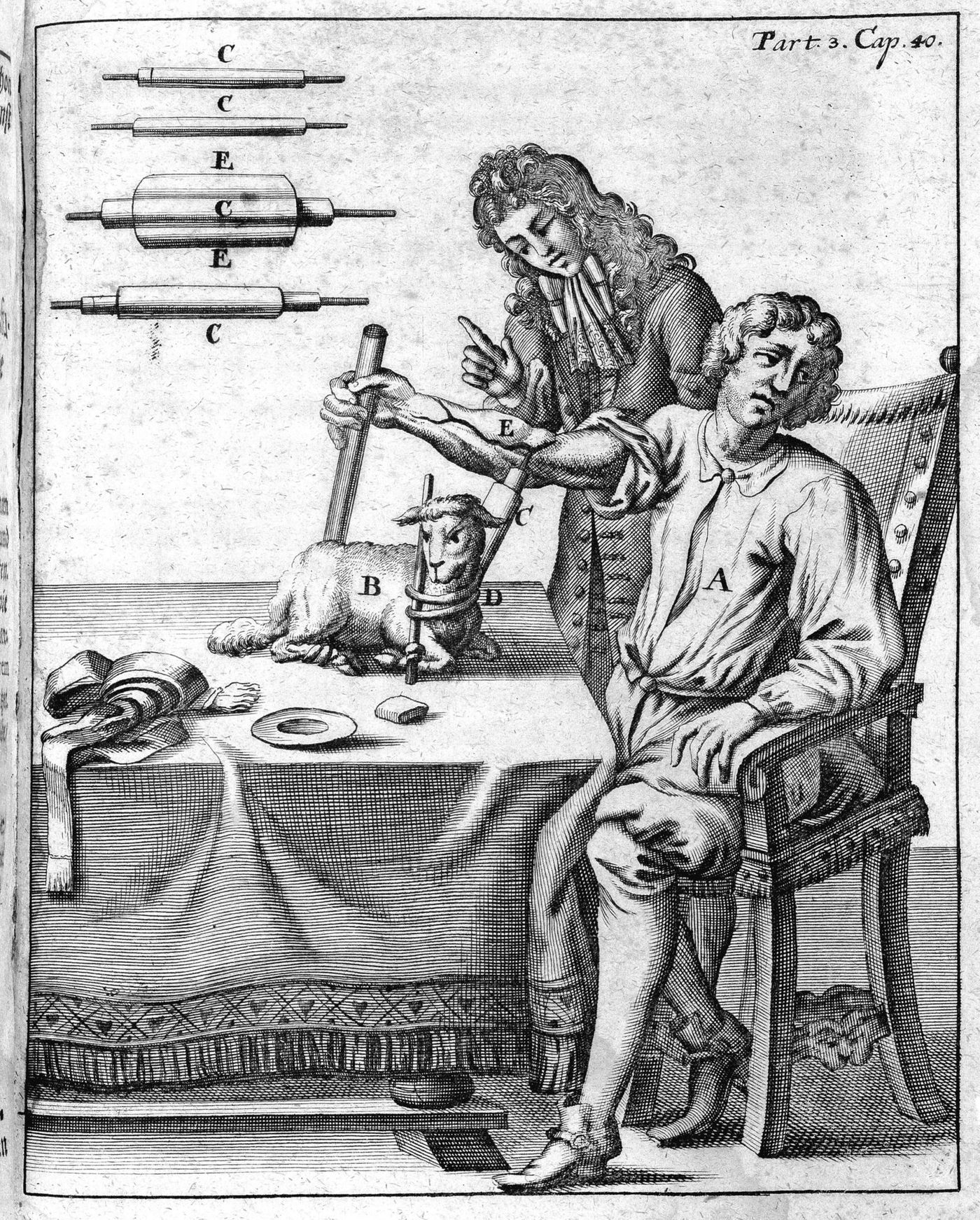

Despite these concerns, humans have long tried to use the skin, blood, and organs of other animals—from primates to cats and dogs—to replace their own body parts. Surgeon David KC Cooper , who specializes in xenotransplantation, notes that such chimeras have been present in stories and religious texts around the world. According to Cooper, these chimeras point to the fact that "for centuries, humans have been extremely interested in the possibility of fusing the physical features of various animal species."

Cooper explained that since the advent of modern medicine, pigs have been seen as having the potential for organ transplantation in humans for a number of reasons: they are infinitely available, they can grow rapidly and have the right organ size. As early as 1838, pig corneas have been transplanted into humans. The 1907 Nobel laureate Alexis Carrel specifically mentioned pigs in his vision for the future of organ transplantation : "The ideal method (for organ transplantation) is to transplant organs from animals that are easy to fix and manipulate, such as pigs."

Since then, medical scientists have made incremental advances in xenotransplantation. In the 1960s, a pig heart valve was transplanted into a human heart to create the bioprosthetic heart valve that is now widely used. However, the breakthrough that brought Carrel's own vision closer to reality was genetic engineering.

In the first successful pig-to-human heart transplant, scientists added six human genes to the donor pig and made other genetic tweaks to design a heart that was more receptive to the recipient's immune system. The principle was confirmed last year when the first pig kidney was successfully transplanted into a brain-dead human recipient (and again in a pig heart transplant a few weeks later).

These developments may herald and drive changes in public attitudes toward xenotransplantation.

Technological advances in the past, along with other changes, have contributed to similar transitions: In Denmark , for example, scholars have documented a dramatic shift from opposition to acceptance of organ transplants over a three-decade period. As Sharp points out, proponents of xenotransplantation, when talking about pigs and other animals, emphasize interspecies relationships (or, as she puts it, the "grammer of Kinship "), which has prompted the public to come to accept it.

On the other hand, changing attitudes towards animal welfare have also raised concerns about the manipulation and exploitation of animals, including the genetic engineering of other species for human health. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals issued a statement denouncing pig heart transplants as "unethical, dangerous and a colossal waste of resources." This criticism reminds us that social attitudes can help Decide if and when a biotechnology can be adopted.

Whatever the long-term fate of xenotransplantation, the therapeutic possibilities suggest that humans and other animals are more alike than we thought.

Gideon Lasco: Anthropologist and physician. Based in Manila, Philippines. He received his PhD from the University of Amsterdam and his MD from the University of the Philippines, where he currently teaches anthropology. His research includes young people's chemistry practices, the meaning of human height, the politics of healthcare, and the realities of life in the Philippines' "war on drugs." Lasco has a weekly column in the Philippine Daily Inquirer with articles on health, culture and society. Twitter: @gideonlasco.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!