From Replica to Simulacrum: The Modern Turn of Literary Consumption

"This article was reproduced from the public account Roof View Research on 2021.8.11 with the authorization of the public account philosophia Philosophy Society"

Author / Migang

1 Introduction

Benjamin, who lived in the early 20th century, personally experienced the great changes brought by large-scale industrialization to culture and art. In his "Artwork in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction", he proposed that the large-scale reproduction of industrialization made the original "aura of art". ”—authenticity, unique status—destroyed; artistic creation combined with cultural-industrial production, deeply embedded in the fabric of society, became a politicized operation.

In Benjamin's time, the newly emerging literary and artistic media were paper prints, photographs, film rolls, celluloid plastic paper, etc. The reproductions spread on these media gradually got rid of the shackles of the ancient principle of "replicating reality". Turn to self-replication. The consequence of this phenomenon is the continuous expansion of the virtual, and the logic of capital seems to have completed the "hidden control" of the public through cultural entertainment. All in all, whether it is capital, fascism or communism, art in a sense has become a tool for these political subjects to influence the public. It is in this sense that Benjamin proposed to use "politicized art" to fight fascism.

Entering the information age, literary and artistic media have undergone a digital turn: digital cameras, the Internet, computer software, and electronic screens have become new literary and artistic media. This time, the mechanical replica completely lost its "prototype" and became a "simulacrum" that self-proliferates in the form of codes; at the same time, due to the opening of digital technology, the public has gained the ability to create literature and art, and the original cultural consumption model Subversive changes have taken place again. As a result, how the cultural media changes brought about by technological progress affect cultural production and thus change cultural consumption and even the cultural form of society has become an important topic.

2 Coded replicas

The myth of complete realism

Benjamin analyzed the creative, cognitive and even political changes brought by reproduction technology to art in "Artwork in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction", and Stigler's philosophy of technology continued his investigation of this theme. Stigler characterizes replication as an ever-expanding fiction:

"Technoscience-fiction" itself is a transmission problem, that is, a major revolution in the problem of reproduction: this "technoscience" is an industry of reproduction, and reproduction is fiction, and some people characterize it as fictional reproduction industry, which, like the devil, is a threat to the world. [1]

Stigler talks about the fictional nature of technological reproduction from the perspective of human subjective acceptance. To be precise, he is concerned with the question of "what do we want". People's cognitive desire for "reality" is overwhelmed by the "invention" of possible things under the mass production of technology industry. Therefore, the reproduction industry of technology science appears as a demon that threatens the world. Starting from a simple enlightenment belief, the mission of science should be to reveal the "truth of nature" for people and satisfy people's essentialist pursuit of "reality"; however, technological reproduction depends on the "possibility" of things, it does not To be subject to reality, rather it turns possibility into reality, is to produce reality. What this inversion brings is a proliferation of fictions that drag society into a symbolic space dominated by cultural production. Stigler named this reproduction “replicability”—originally the production of reproduction, that is, serial production without the original [2].

However, in the era when Benjamin wrote "A Little History of Photography", photography as a reproduction technology seemed to satisfy people's pursuit of the myth of authenticity . "Copying" of nature. Bazin wrote confidently:

A set of lenses that serve as the camera's eye replaces the human eye, and their name is "objectif" (French "photographic lens", which is the same root word as "objectivity"). For the first time in history, there is only one other physical object at work between the original object and its reproduction. For the first time, images of the external world are automatically generated according to strict determinism, without human intervention and participation in creation. [3]

Based on this, Bazin believes that "the aesthetic feature of photography is to reveal the truth" [4]. This myth, which Bazin gave it a name in another review: the myth of the "complete film"—the film that reproduces the full vision of the outside world. [5] If the film has not been able to realize this myth of complete realism, it is only because the technology is not yet complete.

Here, we see two meanings of "replication": as the other verb, the reproduction of the other; as the automatic verb, the self-proliferation reproduction. The photographic works that Benjamin talked about in "A Little History of Photography" and still have some lingering charm are undoubtedly the reproductions of the former meaning, while those in "Artworks in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" that have broken the "authenticity" can be used at any time. Local exhibitions, works of art held by anyone, are reproductions of the latter meaning. Of course, the two meanings are by no means separate. We can imagine that the premise of self-proliferation replication is the replication of other things, that is, the replication of "prototypes". Specifically, the prototypes can be reality, negatives, original films of movies, original works of literature and art, and so on.

However, the logic of replication is not faithful to the prototype. At first glance, photography’s fidelity to reality seems to be guaranteed by some “automatic” operation, but what it captures is not reality, but “optical unconsciousness”—what photography obtains is an image where intentionality has not yet intervened. "Shock" arises from direct encounters with our unconscious impulses that make us see things we didn't intend to see. In other words, the photographic image is the construction of "another reality", and the viewer's identification with the image leads him to enter this dream and accept the image's unconscious adjustment to it. Benjamin wrote in "A Little History of Photography": "Photography reveals in material form the face of all images, including the most subtle details, the clear details that hide in the shelter of daydreams. However, when these details grow to greatness and To the point where they are easily articulated, they are able to establish a completely historical difference between technology and magic."[6] The "completely historical difference" brought about by images as "daydreams" is It is a reversal of technology and magic—images construct reality in the form of "reconstruction" rather than "reproduction". The myth of perfect reproduction is finally revealed as "fictional reality": no matter how similar the content of the image is to reality, it completes itself in its own field; the image first invents itself, and the similarity to reality becomes a derivative. thing.

simulacra database

Baudrillard proposed three levels of "simulacra" (simulacrum) concepts in "Symbolic Exchange and Death" to describe the development process of the history of counterfeiting technology:

- Counterfeiting was the main mode of the "classical" period from the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution.

- Production is the main mode of the industrial age.

- Simulation is currently the dominant mode in this code-dominated phase. [7]

The first-level simulacrum depends on the natural law of value, the second-level simulacrum depends on the commodity law of value, and the third-level simulacrum depends on the structural law of value.

With the Industrial Revolution came the industrial simulacrum of mass production. The universal law of equivalence followed by reproduction can only be established by eliminating the reference to the prototype, which means that "production" excludes the "prototype" in its logical nature, and imitation without the prototype thus becomes a replica of itself, "The real ultimatum is reproduction itself, production is meaningless: the social purpose of production is lost in seriality. The simulacrum overwhelms history."[8]

When the mass repetition of a certain archetype finally becomes the mass repetition of the replica, and the original accumulation finally becomes the self-proliferation of capital, we enter the age of the third-order simulacrum. The production of the third-level simulacrum is like a solitaire game, one character is connected to another without any exact meaning, the continuation of the string itself is the purpose of production.

There are only a few patterns here, from which all forms emerge through differential modulation. It only makes sense to be included in the pattern, and nothing develops according to its own purpose, but comes out of the pattern, that is, out of the "referential signifier", which seems to be a kind of purposiveness, the only plausibility.

It is in the genetic code that the "origin of the simulacrum" finds its perfect form today. On the verge of an increasingly complete extinction of reference and purpose, on the verge of a loss of similarity and reference, one finds numbers and procedural symbols whose "values" are purely tactical, in the presence of other signals (information particles/tests). ), its structure is the micromolecular code structure for manipulation and control. [9]

If we find marble statues, Baroque or Impressionist paintings in the simulacrum of the first degree, and political propaganda, movie posters in the simulacrum of the second degree, then in the simulacrum of the third degree, all we can find Just a combination of some symbols. We can find such a thing in the typical consumption pattern of the digital age - otaku consumption, such as the game planning of "Hyper-Dimensional Game Neptune". From the very beginning, the project was formed based on the anthropomorphic images of several sponsoring companies; the "characters" were first designed, and then other elements that were the main content of the game were filled. Although this propaganda project did not provide any exciting plot or very good game mechanics, it was widely praised by the otaku community. From the design of Neptune, the protagonist of this project [10], we can see the consumption mechanism in operation - the consumption of codes. Personification of game consoles, purple hair, loli characters, and pajamas-like "cute" costumes, these elements either lead to the game culture that is also in the otaku cultural circle, or lead to repeated appearances in the long-term animation character design, forming a certain style. A kind of "traditional" "cute element". The object of consumption is not so much the content of the game itself, but rather the continuous extension to another text chain. This example reveals that there is a generative pattern behind the simulacra, and the text chain left by the process of constant translation and duplication of the code itself becomes the place where the simulacra is generated.

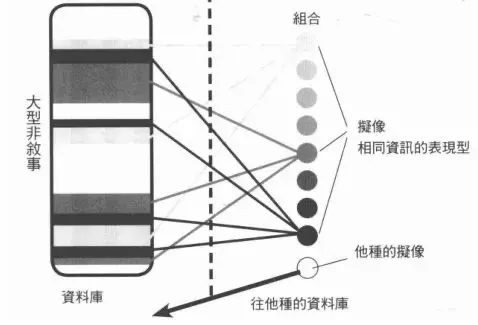

Japanese critic Hiroki Hiroki believes in his book "Animalized Postmodernity" that although Baudrillard's simulacrum talks about the disappearance of archetypes, it simply expresses the generation of simulacra as a disorderly proliferation, rather than an orderly proliferation. Seeing that the archetype-centric tree structure collapsed and was replaced by the so-called "database" model, some new laws and "traditions" were formed. [11]

"Database"[12] is quite appropriate to describe the source of the simulacrum. Just as we can disassemble the above-mentioned characters into a series of code combinations, almost all modern cultural consumer goods can be disassembled in this way. Certain fragmentary features are constantly repeated in the works, thereby gaining a certain "traditional" status, and thus are constantly quoted in subsequent works. Over time, a series of fixed and iconic symbols (like Che Guevara's cultural shirts) have emerged in similar cultural circles, and these symbols can be recombined at any time to form new cultural consumer goods. In this sense, we can say that the "Avengers" series was born in the American comics and Marvel cultural circles/databases, and is similar to "Super Dimensional Game Neptune".

Such a cultural consumption model is to continuously read information in the database, just like clicking links on the Internet, browsing related web pages, related articles, and related videos one by one. The structure of the database can be said to be the structure of the network, and Dong Haoji calls it a “hyperplanar” structure —although the plane still exists, at the same time, things beyond the plane are juxtaposed [13] (hyperlink). The act of clicking on a link does not take us from browsing the plane to some higher level, it just jumps to the next plane. Although large non-narratives (databases) produce small narratives, the reading of small narratives cannot be traced back to the former. The large-scale non-narrative cannot even be properly described, it is made up of countless planes woven together by hyperlinks, always in a process of continuous change, new connections being made. It can be said that the large-scale non-narrative is "latent", just like "pure memory" in Bergson's sense, which flows through all the words produced through mechanisms such as metonymy (reflecting the most appropriate image of this process, It is "relevant recommendation/guess you like it") , and the production of works is nothing more than the actualization of this latent stream, that is, the re-establishment of connections between wandering elements (signifiers) into readable sentences (in A new plane is formed in the database, and the second creation works and the behavior of "playing stalks" can be regarded as such planes). "Readable" does not mean "meaningful", just like the game of Solitaire can be played without knowing the meaning of the words, readability only ensures that it can be connected to another text, and "meaning" is always connected with something other than text. It also means that our browsing behavior is nothing more than an infinite game of Solitaire.

Modern people staring at electronic screens only obsessively repeat such "reading" -- the act of reading information stripped of meaning, or the pure "reading for the sake of reading, putting one string of words into another string of words" Reproduction”, which is exactly what we experience with artworks in the age of mechanical reproduction, or rather, the age of digital reproduction. And this is only the conclusion drawn from the analysis of the change in the form of artwork itself. What should not be ignored is the reinterpretation of this issue in the context of the change in social structure. The examples of the following two films outline the new situation of modern subjects, and we will finally see what kind of cultural ecology the cultural consumers in the new situation have produced around the above-mentioned art forms.

3 The situation of cultural consumers

Two images of the "popular"

The continual expansion of reproduction subverts the dominance of the "archetype," and the Platonic idealistic cult of the "reality" disintegrates with the fading of the aura. As the form of the work of art changes, so does the paradigm of artistic production/cultural production. Moreover, after the mysterious aura fades away, the foundation of the existence of works of art has shifted from a specific field with a sense of ritual to a political category. For example, "original works" have become "copyrights" protected by bourgeois laws; works The production of the economy changed from private commission to cultural industrial production with forecasting of market demand (hence capital logic).

Such changes have connected the public with art like never before, allowing art to penetrate deep into the fabric of society. Benjamin writes: "The mass is the birthplace from which all traditional acts directed towards the new forms of art that are emerging today are conceived. Quantity has become qualitative. The tremendous growth in mass participation has led to changes in the way it is engaged." [14] He did not think lightly that the public had acquired a way of expressing themselves through art because of the public’s participation in art production. On the contrary, he first saw the “secret control” of the public by artistic entertainment, and here On the basis of exploring the possibility of mobilizing the public.

The public does not act as a subject, but always appears in artistic production as an object to be expressed and shaped; the public does not obtain its own "power" through artistic production. We can easily see the split image of the masses in the following two examples: In the Soviet film "Battleship Potemkin" (1925), which depicts the Russian Revolution of 1905, the representation of the "popular" runs through and becomes The most powerful tool for propagating the revolutionary spirit. In the third part, "Blood for Blood," Eisenstein's two montages are particularly typical. The first depicts three shots under a bridge as people go to the port to pay their respects to a sailor killed in an uprising. Eisenstein made full use of the bridge above, the stairs on both sides and the passage below to express the firm and unified will of the "popular" with a spatially layered, orderly and dense flow of people. The second set of shots depicts the scene in which people were incensed and decided to resist the tyranny of Tsarist Russia in front of the bodies of the sailors who were killed. In the first shot, the speaker-like figure stands slightly higher and speaks enthusiastically to the right, while the crowd in the second shot faces the left side of the screen, echoing the orientation of the previous shot. The third shot turns into a close-up, showing the people's long-suppressed anger through the details of a strong arm tightly pinching the corner of the clothes, and the fourth shot echoes the previous shot, showing this anger Emotional outburst.

Crowds are effectively organized and represented as marching masses, stationary masses, shouting masses, and raising their arms, that is to say, the powerful, unified "mass" as the subject of action. Eisenstein's montages construct images for the public, give order to the originally chaotic group images, and set up the grammar of images in a specific assembly method to express abstract "concepts". A similar use can be seen in many films featuring Soviet montages, although there may be a high degree of overlap between the audience at the time and the audience shown in the film, so much so that they could be said to be "self-presentation", but were The public image displayed must have been codified by the grammar of the film, subordinate to the idea that the montage was trying to express. In Benjamin's view that the entertainment of the cinema "undercovers the control of the masses" and has the potential to mobilize the masses, it is also in this sense: the "mass" must first be constructed on the screen, and the people who sit and watch the film can be in this "mass". Find your own image in the public. Although there is the possibility of public self-expression, most of the time, the viewer is only shaped by the identification with the "public image" of the image.

Another example shows the exact opposite. In the Italian neorealist film The Bicycle Thief (1948), the public always appears in a disorganized image, and the protagonist is stripped of all aura and reduced to a member of the public. Deleuze commented:

Identity is subverted, and roles become audiences. He moves, runs, and acts in vain, and the situation in which he finds himself is in all respects beyond his athletic ability to see and hear things that can no longer be resolved by a single answer or action; he is more of a Recording rather than reacting. He becomes a captive of a vision, or is followed by it, or follows it. [15]

This description fits the protagonist's sense of loss throughout the film. His actions are no longer guaranteed by traditional film narratives, and he has lost control of the situation; When it fails, the balance between the characters and the situation is broken, and the protagonist in a "pure audiovisual situation" finds himself helplessly watching and drowning in the crowd. For example, in the following set of shots showing the protagonist looking for the lost bicycle, from the first to the second sub-shot, we turn to the protagonist's subjective shot and see the cluttered crowd; in the third sub-shot, the objective shot, The protagonist seems to disappear into the crowd all at once. Only when we see a person in the middle who hesitates in the heavy rain can we identify him. Realize that the protagonist is just one of the crowd, and it is only because of the stolen bicycle that he has this experience of running around.

In "The Bicycle Thief", the proportion of the crowd is even higher than in "Battleship Potemkin" listed above, however, these moving, noisy people are not related to the words "order" and "oneness". Completely irrelevant, the film does not show any "mass image", because we can't even find what the word "mass" actually refers to, what is presented is just unbearable, overly real and inert everyday life - objects and the characters refuse to provide more meaning outside of themselves. "Bicycle Thief" takes a lot of long shots, but often it just shoots the protagonist from one end of the road to the other, or some insignificant life trivialities. These long takes slack off the film's time, lose its specific theme, and leave the audience at a loss - in the audience's common sense, film editing seems to have an obligation to guide and prompt them "what this clip is saying", but the new reality The long shot of Doctrine is precisely the abolition of this obligation, in an attempt to show something more "real" and unmanipulated. And the confusion of the audience is the confusion of the protagonist, the confusion of the powerless individual who has lost the commitment to the subjectivity of the "mass": the grammar of the film no longer wraps the protagonist, giving meaning to his every move; the protagonist thus finds himself in a In helplessness, he was forced to watch and record, but was unable to make any effective response. This is the exact opposite of the aforementioned montage, where the protagonist's words are expressed on a conceptual level through the "magic" of editing, or the image of the protagonist itself becomes a device of expression, arousing people's recognition. In this way, the purely audiovisual situations and long shots of Neorealism are the disenchantment of the magic of montage.

From this, it can be seen that the individual in the age of mechanical reproduction hosts a divided image of the "mass": on the one hand, the social/political entity makes a sovereign commitment to the individual, reducing each citizen to that powerful, unified in the myth of the popular masses; on the other hand, the individual will find himself in the midst of unfamiliar, cluttered crowds/masses, helplessly forced to watch and record what is in front of him, but not be able to respond effectively. Under the new logic of art production, cultural production is incorporated by political power. In this case, it is not so much that the individual cannot guarantee his right to speak, but that the individual is captured by cultural production itself—he can only identify himself as Only a member of the former "mass" can avoid the terrible situation of helplessness.

postmodern cultural tribesmen

Stigler pointed out in a lecture titled "The Emotional Proletariat" that along with the development of the cultural industry, consumers' sense of proletarianization has become proletarianized, and this "proletarianization" refers to the loss of knowledge[16] - People who listen to music on the radio lose their knowledge of playing, and people who appreciate paintings on paper have no knowledge of the art of painting. Such technological developments have impoverished the knowledge of amateurs and degenerated into cultural consumers.

However, with the replacement of industrial technology by digital technology, there is a second mechanical turn of sensibility. The cultural production tools originally controlled by capital marketing and the cultural industry have been digitized and opened to the public, and everyone can master video editing, post-production, electronic drawing and other technologies through the study of computer software. This shift brought about a revival of amateurs, and cultural consumers finally regained some control over the libidinal economy :

What is an amateur if he is not a symbol of libidinal economy? Amateur "to love" (amat comes from the Latin verb amare, which is "to love"): this is exactly what makes an amateur an amateur. Art amateurs love works of art. And as far as they love art, the art works for them too.

Every work of art is, to some extent, a revelation of itself, and only by revealing itself as a revelation can it truly reveal itself, thus forming a certain doctrine. This has in some cases led to the formation of schools, sects, certain sects, and sometimes even sectarian splits. Kant said that when I regard a work of art as beautiful, I must think that everyone should think it is beautiful; but, deep down in my heart, I know that the situation will not be as I want it to be That's what it is, and it never will be. [17]

What Stigler first reveals here is the political conditions under which art works in the digital age can be formed—it is because of the love of amateurs that art becomes art, and culture and cultural fans are simultaneously constructed in the process. . Further, this passage also reveals the current tribalism of culture in the digital age—just because culture is produced by the fetishes of amateurs, the corresponding “religions” have arisen under the “god” of culture. The Order repeats certain teachings internally and opposes other Orders externally. Combined with the analysis of the cultural form of the "database" above, we can say that each sect shares a smaller database, which is located in a larger database, and is closely related to the database. The other databases below form an opposing relationship, which is the set-theoretic structure in which different discourse systems are nested.

Therefore, although the "helpless subject" we analyzed above must identify with a certain "mass", in the postmodern situation, this "mass" is not necessarily the capitalized "all the people", but can be It has been disassembled into countless lowercase “masses” ; if this helpless subject threw himself into the embrace of culture and became an amateur of a certain culture, then the “masses” he identified with would be some kind of “fellow”. Society” and “cultural circle”, where he can establish connections with others, use the same discourse system, share and even co-create cultural consumer goods.

However, such a mode of cultural consumption brings cultural tribalization :

Unlike the "big narrative" represented by history, the "small narrative" generated from the database does not hold the basis for this division (referring to the "public standard" defined by the sovereign). Therefore, in order to defend their own legitimacy and habitat—in order to exclude noise and mismatches from their own identity, in order to more closely distinguish between enemy and self, internal and external, many small narratives must exclude and attack other narratives. Therefore, the commonality of the mini-narratives generated from the database has the character of exclusivity. [18]

Japanese critic Tokihiro Uno continued Hiroshi Hiroki's discussion of database culture, revealing the resulting problem of an exclusive society, that is, how people in different cultural circles/mini-narratives communicate. Dong Haoji continues the idea of database theory, and believes that the products ("characters") generated in the database are interconnected, and the relationship network between codes opens up the possibility of communication between different small narratives. And Uno Changkuan criticized this point. Although the role can be reduced to a symbol with some kind of sharedness, the process of establishing the role is precisely the negation of its constructive factors - only by denying its original composition sex, an exclusive narrative can be established, and a cult-like identification with that narrative is possible:

Strictly speaking, a character is not a token. In order for a character to be established, the commonality of the character setting needs to be acknowledged, because the commonality is dictated by the story (narrative). The characters are independent of the original work, and then are changed and consumed in the second creation. This process further strengthens the recognition of the commonality of these settings at the meta level, and the story (narrative) that defines this commonality.

Dong Haoji's discussion failed to notice this. Dong Haoji proposes the concept of "roles" in database consumption as a kind of "narrative criticism". Often, however, roles are things that provide and complement commonality. It's not an exaggeration to call characters the source of a "mini-narrative."

It's technically possible to have communities connecting the world, but at the narrative level it's impossible. It's a small narrative without internal errors that can only be connected by someone who acknowledges the character's setting. Dong Haoji believes that characters are free beings (or symbolic elements that represent such beings) that can transcend "mini-narratives", and his claim ignores the above arguments. [19]

From the perspective of work production, postmodern digital technology seems to bring us a vast cultural space of connection and sharing - people can arbitrarily take codes from various databases, add their own Creativity, creating new image-character-work. From this point of view, it seems that a character as an integration of multiple codes can become a "sign" connecting different cultural circles with its certain universality, but Uno pointed out that this is precisely a reversed logic - using a code The work/character image put together from the fragments denies the fact that "oneself is put together" at the moment of birth, creates an essential image for oneself, presents oneself as something unique, and becomes the source of exclusive narrative, " Statue". Treating characters as an existence independent of a small narrative is a complete misunderstanding of the logic of database cultural consumption. The commonality between characters seen at the meta level cannot be a channel of communication for "believers", rather characters The similarity may even lead to apologetic exclusion, that is, only the roles that one identifies with can occupy these symbols; if the roles are misidentified due to this similarity, it will only lead to the ridicule of "doing not know how to do it". The character is exactly the xenophobia of the tribe.

The postmodern database cultural consumption model itself does not have the criticality of the discourse system, that is to say, the "cultural tribesmen" who are addicted to the small narrative cannot find the possibility of "communication" (with others) in it. In fact, the cultural tribe was established based on the exclusion of this possibility, and the real "communication" is nothing but a myth of this era. In the postmodern situation of the decline of the grand narrative of culture, although people do not have to agree with the capitalized political aesthetics shown in "Battleship Potemkin", modern people who are liberated from this obligation can only survive in closed among the cultural tribes.

Therefore, it is still pointless to criticize cultural consumption only from the broad and opposing perspective of "the cultural industry under the control of capital will manipulate personal aesthetics". The more immediate problem is that the cultural ecology itself has become more and more isolated and exclusive tribalism ; it's not just a matter of production, "outside", but first of all a matter of cultural acceptance, that's "inside" - not some conspiracy-theoretical capitalist giant machine separating people, but It is the tribesmen who must refuse to communicate ; in other words, cultural acceptance is based on the refusal to communicate, and the form of culture encourages this xenophobic character. To make matters worse, there is the possibility that the artistic image and discourse system shaped by the culture industry will drown the weak tribes fighting each other, causing a "third mechanical turn of sensibility" - a large cultural machine will turn the creativity of amateurs. Incorporation, shaping the "unified" social aesthetic and cultural standards. Although the aesthetic standard can never be truly unified, it can be "sovereign", and it will suppress all narratives outside it with the huge image of the "social whole" . Literary and artistic works will be re-branded with politics, only this time not in the name of political ideology, but in the name of "popular aesthetics".

4 Conclusion

In the contemporary context, artistic aesthetics and cultural consumption are more closely integrated, and their political nature is not lessened than in Benjamin's time: it has become a new form of social connection after the dissociation of traditional interpersonal bonds, and It also has the function of "belief", although this function has lost its original sacred meaning . The cultural consumer is still the powerless, image-captured, obsessive-compulsive image of repetitive viewing behaviors, but the database model also brings new possibilities for cultural creation. We may, like Deleuze, expect the differentiated repetition of cultural codes to outline the escape line and escape the capture of dominant discourses, but we also have to admit the conservative character of this differentiation process itself, and the modern context Closeness, exclusivity implied by the word "aesthetic".

This closed character is not produced by the subjectivity of perceptual aesthetics, and people are not mutually exclusive because of different feelings about the same work. If it is said that in the "shocking experience" described by Benjamin, people accept the following novel stimuli with sensibility, then in contemporary simulacrum aesthetics, the function of sensibility has almost relegated to the background, replaced by the function of "reading" - The elements that make up the work are translated into words, thereby extending the text chain in the database. All representation mechanisms become "referenceable". Here, it is not the general ability to read that breeds exclusivity, but the context and object of reading, that is, the specific database and cultural circle. That is to say, it is not the aesthetic itself, but the situation in which the aesthetic subject is placed that brings the closure; this aesthetic subject is still captured by the work, but this time it is not just passive, sensually overwhelming, but active... /

Notes and References:

[1] [French] Stigler: "Technology and Time 3: The Problem of Time and Existential Pain in Film", translated by Fang Erping, Nanjing: Yilin Publishing House, 2012, p. 266.

[2] Technology and Time 3, p. 283.

[3] [French] Bazin: "What is a movie? ", translated by Cui Junyan, Beijing: China Film Press, 1987, p. 11.

[4] Ibid., p. 13.

[5] Ibid., p. 21.

[6] [French] Benjamin: A Brief History of Photography, translated by Xu Qiling and Lin Zhiming, Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, 2017, p. 27.

[7] [French] Baudrillard: "Symbolic Exchange and Death", translated by Che Jinshan, Nanjing: Yilin Press, 2009, p. 61.

[8] Ibid., p. 70.

[9] Ibid., pp. 71-72.

[10] Image via compileheart.com/neptun.

[11] [Japanese] Dong Haoji: "Postmodern Animalization: How the Otaku Influenced Japanese Society", translated by Chu Xuan Chu, Taipei: Gaobao Book Group, p. 93.

[12] Figure 2 is from p. 94 of "Postmodern Animalization".

[13] Ibid., p. 160.

[14] Hannah Arendt, "Enlightenment: Selected Works of Benjaming", translated by Zhang Xudong and Wang Ban, Beijing: Life·Reading·Xinzhi Sanlian Publishing House, 2008, p.260.

[15] Wu Qiong ed. "The Pleasure of Gaze: Psychoanalysis of Film Texts", Beijing: Renmin University of China Press, 2005, p. 185.

[16] [French] Stigler: "Art in the Anthropocene: Stigler's Lecture at the China Academy of Art", translated by Lu Xinghua and Xu Yu, Chongqing: Chongqing University Press, 2016, p. 37.

[17] Ibid., pp. 40-41.

[18] Totsuhiro Uno: "Imagination in the Age of ゼロ", Tokyo: Hayakawa Shobo, 2013, p. 30.

[19] Ibid., p. 34.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More