The Convention on Biological Diversity: Taiwanese journalist's notes from UN conference interviews

From June 20th to 26th, with a grant from the Earth Journalism Network, I traveled to UN Environment, Nairobi, Kenya, on behalf of End Media, to present a briefing on the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Conducted interviews at the negotiation site of the Sexual Framework.

You are welcome to take the time to read the report published by Duan Media . We have used a very "light" space to help you summarize the highlights of this conference.

I really learned a lot from this trip to Kenya. Whether it is the negotiation process of international agreements, the reporting methods of meetings, or the latest controversies in the field of biodiversity, everything is new and fascinating to me.

It was the first time I went abroad as a reporter to cover a meeting with the United Nations. In fact, I was a little nervous until now—especially when it was reported in May that a Taiwanese reporter was rejected by the United Nations in Geneva, so I was always worried before leaving. He would also be unable to enter the United Nations Environment Programme in Kenya.

During the interview, I had a chat with the media liaison of the United Nations. He said that it was fortunate that Earth Journalism Network put me and other sponsored journalists together and applied for an interview with the United Nations. Not so lucky.

At some point, though, being a Taiwanese can be a little embarrassing.

When I entered the UN campus on the first day, the reporters in the same group were excited to take pictures with the national flag of their own country; the Bangladeshi reporter kindly wanted to help me take pictures, but I could only explain to him that there is no Taiwan flag here.

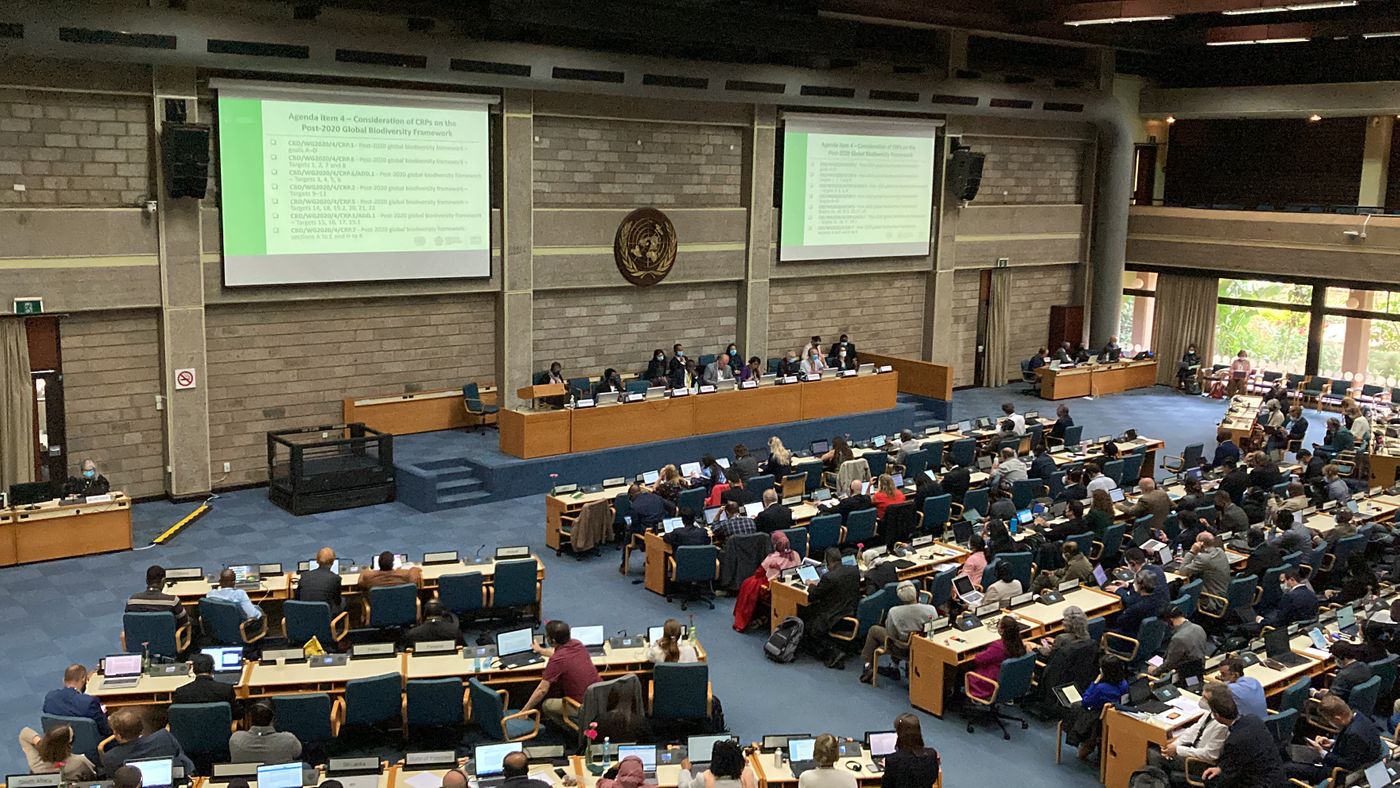

The first time I came to the United Nations to witness the negotiation scene, the biggest impression was that multilateral negotiations are really very hard work.

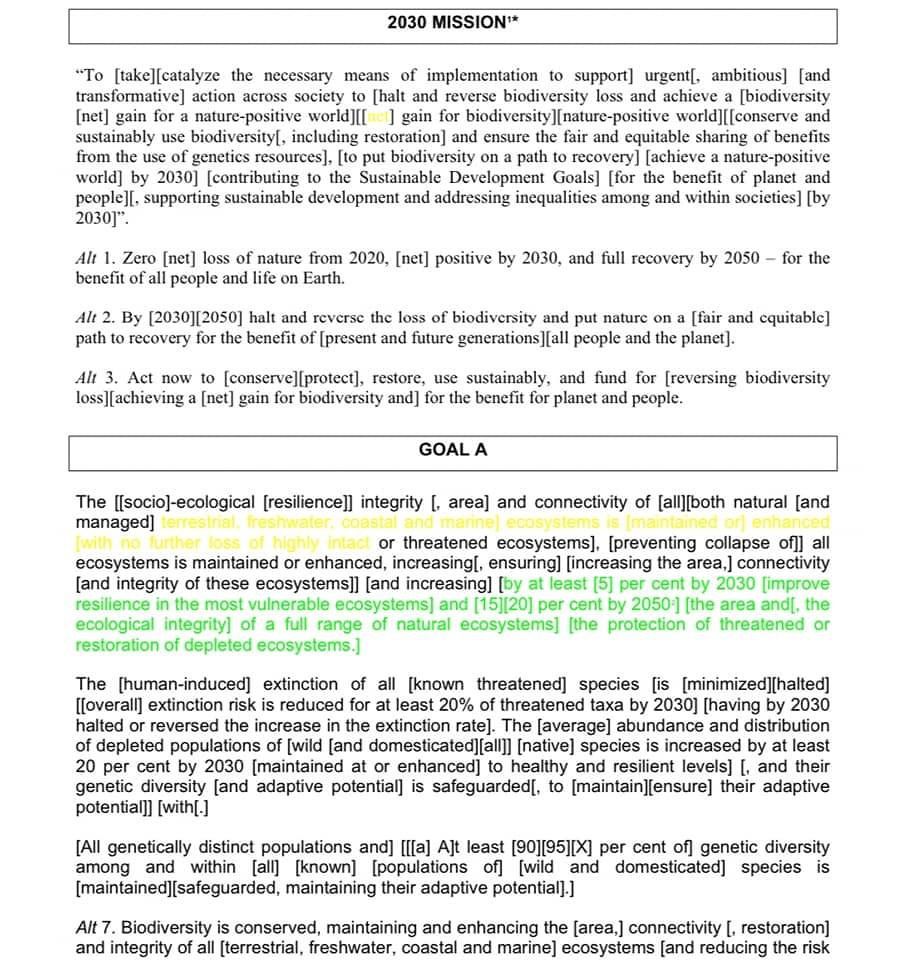

You start by reading through the bracketed, almost unreadable draft, then sit patiently in the conference hall waiting to speak, and the session feels like a marathon with few breaks.

You may spend hours, but you can't even solve a few sentences, because every word and punctuation is a big deal, and it is related to the fate of the entire ecosystem in the next ten or even thirty years.

As a person in the gallery, I often feel that you are more like "writing a dictionary" than they are negotiating.

For example, in the provisions on the scope of protected areas, delegates spent half an hour discussing whether to change "waters other than the ocean" from freshwater to inland water (domestic waters/inland waters). ), because some inland waters are not necessarily "freshwater" (such as the Aral Sea in Central Asia).

"Is it a big sea or a big ocean?" The definition issue they spent two hours discussing is another more classic example.

But having said that, the main reason for discussing these is this: this framework for providing a global approach to biodiversity development has a big ambition-it hopes that by 2030, at least 30 percent of the Earth's surface will be covered % of the area is designated as a "protected area" to restore lost biodiversity.

But here comes the problem.

How is the so-called 30% defined? Is water and land each 30%? Or add 30% of the two?

Similarly, does each country have to contribute 30%? Or does the world add up to meet the standard? If the latter, how do you determine who is contributing more and who is contributing less? Like carbon rights, will it become a developed country that gives money to developing countries, telling them not to develop the economy and to set up more reserved areas?

More importantly, it is simply impossible for a strongman to designate 30% of its land area as protected areas in such narrow and densely populated countries as Bangladesh and Singapore.

For me, this goal also involves another, more important question: many of the areas that are to be designated as protected areas are actually occupied by people - these people are you going to force them to move? Should they be banned from producing in the reserve?

Since many of the people living in these protected areas are indigenous communities, this framework also emphasizes one thing: the protection of biodiversity and the establishment of protected areas should not sacrifice the survival rights of indigenous peoples, fishing and hunting. right.

And this is also the part of this framework that is most relevant to Taiwan-in Taiwan, the hunting rights of the aborigines in the traditional fields are also an issue that has been discussed continuously by various parties in the past few years and is still unresolved.

As for the impact of this framework on the issue of "self-management of hunting" in Taiwan, you are welcome to click on the link to the report above. The text briefly describes the response of the proponent Lu Yiqi; after returning to Taiwan, we will also address this issue. More in-depth follow up.

Another controversy that I find interesting is a relatively new issue: DSI.

DSI in Chinese is "digital sequence information", which is the biological gene sequence stored in the form of "digitalization".

The reason DSI is controversial is simple: Thanks to advances in technology, scientists today can inexpensively and efficiently sequence biological genes—gene sequences that can be stored in digital form in various genetic databases, The data in these databases can be accessed by anyone.

However, these databases also allow large seed, grain, and pesticide companies to directly obtain these gene sequences for free, and then synthesize them in the laboratory without having to go to the origin of a certain species to collect them.

At this time, the origin of these creatures began to feel inappropriate: these biological resources are clearly from my country, why do you use and profit, but we can't share the money?

There is another key behind this question:

The areas with the richest biodiversity in the world today are basically concentrated in developing countries on both sides of the equator; multinational corporations in developed countries make a lot of money by relying on organisms in developing countries, but they do not share profits with developing countries. It is not in line with "fairness and justice", and it is difficult for developing countries to have incentives to protect their own biodiversity.

So one of the goals of this framework is to discuss how the benefits of DSI should be shared fairly.

To me, what's interesting about DSI is that it reflects the human imagination of "ownership" and involves an extension of both ways of imagining.

One of the characteristics of human beings is that they use abstract laws, habits, and even a whole set of cultural structures to regulate "ownership", and now this ownership has actually extended to "non-human biological species".

What's more interesting is that this kind of "ownership" of human beings is held in units of "sovereign countries" - for example, pandas are endemic to China, so the ownership of pandas' genetic sequences is in the country of China. Hands on; if you benefit from using panda genetic sequences, those benefits must be shared with China.

In other words, this human imagination of "ownership of biological species" is actually intertwined with the concept of "sovereign state" - and "sovereign state" itself, that is, human imagination "a certain piece of land, a certain sea area belongs to some form of "ownership" of a certain group of people.

Finally, I would like to mention some inspirations that biologist Paul Leadley gave me during the interview.

He told me that there are two reasons why biodiversity does not receive as much attention as the issue of "climate change":

First of all, climate change affects our daily lives, so everyone can feel the crisis; but the scenario of biological extinction is very far away, so we are not very easy to feel the impact of biodiversity loss.

More importantly, we can quantify the damage that climate change is causing to us, convert the damage into monetary amounts, and even turn climate change into a set of money-making tools and use market mechanisms to solve climate change problems (such as carbon allowance trading markets) ; In contrast, the issue of biodiversity has not yet developed such a mechanism.

That's why, more than a decade ago, Paul Leadley said, there was a kind of "paradigm shift" in the "conservation discourse of biodiversity" -- that is, from "conservation for species" to "for people themselves." The purpose is to hope that the issue of biodiversity can be more sensitive to the general public.

But he also reminded that from a scientific point of view, there are actually many problems with this argument, one of the most obvious is that biodiversity has a lot of value, which cannot be quantified or converted into monetary value.

Just before this story was published, I had a very dramatic evening.

According to the schedule, on the last day of the negotiations, the UN official should announce the results of the negotiations over the past week and the framework documents negotiated at the press conference on the last day.

However, early in the morning, we received news that the regular press conference was cancelled. Even the closing press conference in the afternoon was postponed and postponed until 9 o'clock in the evening.

The reason for these changes is simple: the negotiation did not go well, and only one of the 22 objective clauses was finally negotiated, which once again demonstrated how difficult the consensus-building process of these international conventions is.

Finally, I would like to thank Duan for being willing to let me out, spending so much cost to report on a very important topic that few people pay attention to.

Thanks also to the Earth Journalism Network for funding this interview and for giving many professional interview advice; working with journalists from all over the world has been an invaluable and wonderful experience.

If you have never paid attention to the issue of biodiversity, then I hope that this report from Duan Media and this post-2020 global framework can become a starting point for our attention.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!