From interviewer to artist, a subtle power swap observes

An article published in "BIE Others", click here to jump to the original text .

Author: siqi Editor: Rice

In the process of my Yeluzi learning and interviewing, artists and practitioners in the art industry have always been one of my main interview groups. But with more experience, the job hasn't gotten any easier for me. I don't know why, but I hesitate for a long time to do something very simple for other journalists.

I used to think it was a manifestation of "social fear", but recently when I tried to figure out how it all happened, I found that what I feared might not be socialism itself, but the power that flows from behind it. relation.

It's over, I've made friends with the artist

"It's over, I've made friends with artists." One night a few years ago, this sentence popped into my head when I was having dinner with two dozen artists at a place near 798.

At that time, I was a college student preparing to take the postgraduate entrance examination in journalism and communication. I was a complete outsider in journalism and art.

Before that, it wasn't that I didn't try to make friends with artists. I once found some graduates of the Academy of Fine Arts and said that I would like to help them write articles and so on, but I was turned down because of my unachievable undergraduate major. Later I saw it too, because big truths like "journalism professionalism" reminded me that if you're too close to your interviewee, you're likely to be too sympathetic to write objectively. everything observed. So the smartest way is to maintain a distanced connection.

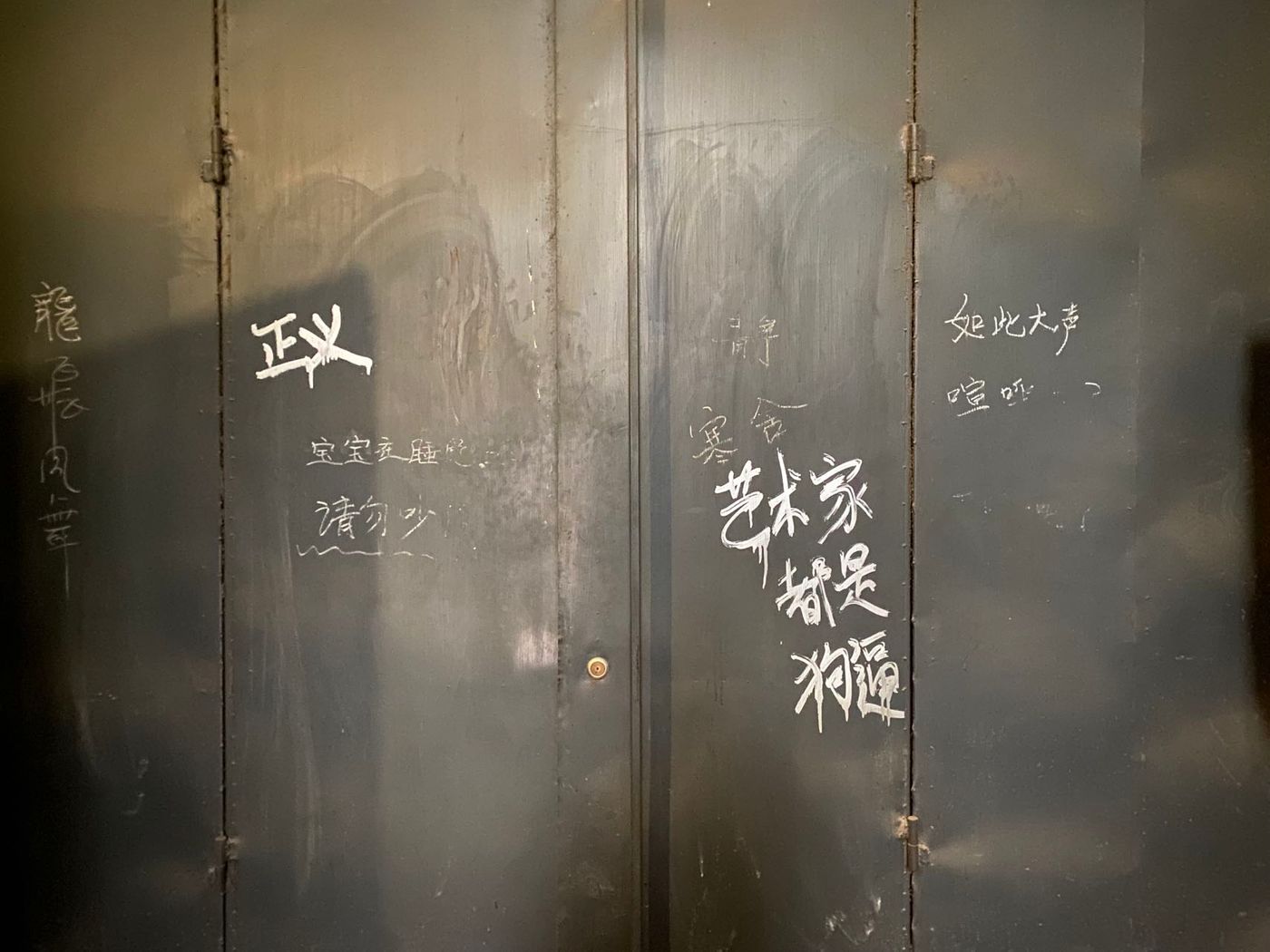

The potluck that day came after the opening of an exhibition. The content of the exhibition is the creation of artists using local materials after an art district was demolished. Two days before the forced demolition, I saw an artist in the circle of friends who added WeChat to the exhibition and said that the art area where he was located was suddenly posted with a notice to move out within 3 days, so he planned to do it in his studio. The last exhibition. I couldn't hold back my desire for "presence". I started from the remote postgraduate entrance examination base and went to the same remote art district where they were located.

This unplanned onlooker broke my life experience of only admiring art in a clean white box-like exhibition hall. Among the artists who have gone through the demolition together, there are many people I have only seen in well-known art museums and media reports. Every time I pass an unfamiliar studio, the people inside will take the initiative to greet me, "Come in and have a look." A photo I took that day that was later used as their exhibition poster. A very immature written record was also published a few months later.

During the whole process, the excitement of "it's good to be friends with artists" and the torture of "Should I be friends with artists" repeatedly prevailed in my heart. On the one hand, I'm not doing an investigative report on anti-criminal and evil, but from my perspective to write down what I have seen and heard, so making friends shouldn't affect the credibility of the article, right? On the other hand, I was worried that if I wanted to become a full-fledged reporter in the future, would this approach seem unprofessional?

I thought that by the time I started my career path, with enough training, I could be an objective person behind the mask of an "interviewer". Unexpectedly, as I met more and more artists, the time and energy I spent thinking about "how to make friends and ensure independent reporting" has far exceeded the interview and writing itself.

Where is my problem?

"Just you, still want to interview the artist?"

Some of my more formal interviewer careers began during my senior year internship. One of the topics I chose for the newspaper was about a well-known art district.

In the beginning, my interview subjects were all introduced by my boyfriend at the time. Different from the rhetoric of most artists "indifferent to fame and fortune" and "pursuing spiritual resonance", he always said that artists will not chat with you for no reason. So, every time we go to meet other artists, we either bring some fruit or buy something from each other. He said, half-jokingly, that he had already spent a lot of money for me to be able to complete the interview. But actually, on those occasions, I couldn't say a few words at all.

I soon realized that relying on men or money is not a good way to work. I started to read other media reports and found an interesting person, I'll call him J for now. Originally, J knew nothing about art and was a black car driver, but he has drawn many artists, and he has become familiar with local bigwigs. Slowly, he began to collect works and autographs, and even opened his own art gallery with these collections.

I added J's WeChat and introduced myself to him, "Hello Mr. XX, my name is Siqi, and I especially want to chat with you," Yunyun. He quickly agreed and asked when I would arrive in Beijing. I said, "I've been in Beijing." He asked, "Aren't you in Taiwan?" I said, "That's Fang Siqi in Taiwan, a character in a novel." He replied, "Oh, then I don't. Accept your interview."

Such rejection is not necessarily a bad thing, after all, it made me feel the absurdity of this art district. Later, to get more and different perspectives, I started chatting up strangers in small restaurants. This is a very good way, because in that art district, even the delivery people are painters who can't sell their paintings.

One day, I met a male painter A who recommended male painter B to me. A said, B has been here for many years, and he is the kind of artist that can be found on the Internet. You will definitely gain something from chatting with him.

The next afternoon, I came to B's studio, and we chatted while flipping through his albums. He is indeed a storyteller. Whenever an important scene is mentioned, he will shake his arm and his eyes will be fierce, revealing a desire to perform. During the interview, calls kept coming, asking him to go drink. After rejecting it three times, he finally asked me, "Would you like to have dinner with me? Let me introduce you to a few more artists." I was very happy, thinking that this must be a great opportunity to get closer to their real lives.

At the door of the male painter C's house, B stopped and said, "Come on, you take my hand, so that they know that you are the one I brought and they won't bully you." I looked at the person in front of me. B, he is older than my father, and there is no shortage of online reports, so it should really be to take care of the younger generation, right? While I was still thinking, he had already pulled my hand up.

As soon as I entered the door, the two artists inside were very enthusiastic, and no one wanted to bully me, so I withdrew my hand. They started to drink, and like their elders, they persuaded me to drink together, "You don't need too much, just what you want."

From the moment their faces started to flush, things changed. An artist in the system with half-grey hair suddenly stood up, slapped the table and yelled at me, "Just you, still want to interview an artist? Who do you think an artist is? Is it someone you can interview if you want? Artist Would you say it to others casually?!"

Not to be outdone, the married male artist sitting on my right asked me, "If you want to interview us, can I interview you too? You answer one, and I'll answer you. My first question is, How many times a week are you and your boyfriend?"

The only female artist on the left answered for me before I could speak, "You tell him, eight times a day, to piss him off."

And the B who brought me, was lying on the sofa with his feet up, laughing at the absurd scene - nothing like the fearful, repressed eyes of his work.

When the female artist was about to return to the studio, I quickly stood up, "I want to see your studio!"

I followed her out of the wine bureau temporarily. In her studio, she wrote a letter, and every now and then she looked back and asked me how I was doing. I haven't studied calligraphy, but I think it's really beautiful. When it got dark, I said, "I have something to do, so I'll go home." But she insisted on taking me back to the dinner to say hello before leaving. Perhaps seeing my discomfort, she advised me, "When you are with a man, you have to treat yourself as a man. Do you understand what I mean?"

I tried to understand, but found that it wasn't something I could do with effort. After a while, that article of mine was nearing completion. One day, I called B to confirm the details. He said in a drunken voice, "I mentioned you to a few artists again yesterday, and I told them that your butt looks really good."

I pretended not to hear and continued to confirm some questions such as the year and the person's name with him. After hanging up, I never contacted him again.

In order not to let the efforts of more than a month be in vain, I still published that article. Looking back on the writing process at that time, I seem to be doing subtraction unconsciously to minimize the impact of my age and gender on the article. It's not that I'm being told to do this, it's just that I've never seen other journalists not.

I often think that if I were replaced by an older, male reporter with sufficient voice, I would not have so many concerns, right? Maybe that's the objective, neutral point of view that people acquiesce in. And the farther away I was from that character, the more scraps that needed to be cut. This seemingly a priori consensus protected both me and the interviewees, they retained their aura as an artist, and I got an internship. But until now, I don't know whether to thank them for their cooperation, or to be wary of being used again by them.

Some myths about professionalism

After the article was published, an art worker within the system that I interviewed but did not write in the article asked me why I hadn't confirmed the manuscript to him in advance. I said that I am very grateful to him for bringing me a lot of ideas, but I did not quote his original words in my article, nor did his name appear. He only replied with four words, "You are not professional."

Of course I disagree, but I didn't reply.

As for whether to confirm the manuscript to the other party, if it is in a specific media, it may be possible to follow the editor's regulations. But as a freelance writer, I've never had a standard practice. I asked a friend who is a social news reporter, and she insisted that the interviewee should not be shown the full article, so as to avoid the other party making too many demands for their own purposes. But at the same time, I have also heard complaints from friends who work in art museums that some media publish articles without prior confirmation, resulting in wrong years and numbers, which is too unprofessional.

Things get more nuanced if the interviewee doesn't just have the label "artist" on them. In the gap year after the internship, I interviewed a musician who, by another identity, was a very good reporter in the golden age of journalism. I was able to interview her because it was during the promotional period before her performance.

I sat in front of her nervously that day, and before she had time to speak, she started looking through her bag and said she brought me a present. In an instant, countless thoughts flashed through my mind: She is not a media person today, but an interviewee, so I don't think I should accept gifts? But I'm not an official reporter today, I just came here because I like her. It seems that it doesn't matter if I accept it? She is so experienced, she must know when to give gifts and when not to, so listen to her, you can't go wrong, right? But I didn't prepare a present for her, what can I do? ...

The interview that day gave me a good impression of her, but in the process of writing the manuscript, it took a long time to write, but it was still written like a mess of sand. There was no editor to guide me, so I had to send it directly to her. She didn't make major changes to the article, but just added a few sentences and it became a lot smoother. Inwardly, I accused myself of being unprofessional and excused myself by "taking a free writing class".

Later, I found a well-known public account in the music field to publish this article. In fact, it is the only one I know. There is no royalties, the biggest gain is that some people praise me in the comments.

After a while, I met her agent, who also works in the media. I was very insecure, so I asked the agent, am I writing too badly?

He said, "I didn't read it at all. It doesn't matter what you write, as long as it can be posted on that platform."

In my opinion today, he was right. The right to speak is more like a social relationship than a handicraft that has been polished for ten years behind closed doors.

Gradually, I published more and met more people, and no one would pat me on the table and ask me, "Just you, do you still want to interview artists?" Instead, more and more artists want to talk to me. I chat. Some would say, "Our industry needs people like you so much." I asked, "Why?" They said, "Because we don't know how to promote ourselves, we need people like you to help us. On the one hand, some people want to be reported by the media, but on the other hand, they can't let go of the air, so they say, "Let's make the art career better and better together."

Of course I am not willing to be their propaganda tool, but I will not take the initiative to shirk it. Because I gradually discovered that when dealing with artists, the last thing to believe is compliments.

There was a middle-aged male musician who said before the interview that what I did was meaningful, but after the interview he said that I was not good enough to ask questions. I quickly asked, "Is it because I didn't study music and didn't ask any professional questions?"

I ask this because the professionalism of art really conditioned me during that time. I'm tired of asking questions like "How did you start making art" and "Tell me about the thinking behind this piece", and I often imagine if I could casually exclaim in front of a musician, "The XXX chords you use are very good. Features, I like it", or when looking at a painter's work, pretending to inadvertently ask, "Are your brushstrokes and structure influenced by the XX genre in the XXX period?" - They must be impressed by me, right?

But he said, "No, it's because you don't know that we don't make money doing pure instrumental music."

I had the urge to ask him back, "Then do you think you understand interviews?" But when I was thinking about whether it would be rude to ask the interviewee, he said, "But I don't blame you. I know. Why? Because you're a girl!"

Then, not knowing whether to add to his humor, he invited me to toast. I didn't ask, "What misunderstanding do you have about girls?" After all, he ordered the wine. I'm really unprofessional at this point.

Who is not an artist anymore?

I'm probably not a good reporter by being so forward-looking and inefficient. But luckily I have another trick, which is to turn myself into an artist.

The long-term photography habits have helped me to accumulate a lot of works, and slowly, friends began to invite me to participate in exhibitions, or suggested that I hold exhibitions by myself. At the end of last year, together with another friend who had just resigned from the media, I held a duo solo exhibition that was not very serious.

At this point, the media experience does not know whether it is a good thing or a bad thing. The manager of the venue has been working in the art industry, and our debate with her started with the pre-show promotion. In order not to be too different from other tweets on the platform's official account, she suggested that we put more pictures and not so many words. And the two of us insisted on maintaining the author's final dignity: only 1,000 words, which is already very few!

The exhibition started, and we finally realized the artist's privilege—even nonsense, it is no longer ordinary nonsense, but nonsense with artistic temperament. The time we spend in that room is also the time that condenses the essence of human wisdom. Although we have an infinite amount of openness, tolerance and love in our hearts, the physical body cannot get rid of the basic needs of eating, drinking and sleeping. Moreover, at this time, we are no longer college students who will be happy for several days after being praised. Now we want to discuss art with us, either talented or rich.

At the same time, the feeling of having the right to speak in the media is even better. At the exhibition, when we meet other media workers, the most common thing we say is "Welcome to ask us for a draft", not "Do you want to write about us?" I made an appointment and asked me if I could reveal some of my next plans. I blurted out without thinking, "No!"

After the exhibition, I wrote the whole exhibition process as an article and published it. As a result, a new question arises. When I meet the artist again in the future, should I let them know about the existence of this article?

The reason I want to send it to them is that there is finally one thing that succinctly proves that I'm not all that ignorant about art either. The reason why I didn't want to post it was that the article was very offensive and satirized many men. What if they thought I was a crazy woman and avoided me even more after seeing it?

I've tried different strategies on different people, but it doesn't seem to make any difference, because most people's attitude is a simple "too long to watch". Moreover, since I didn't really internalize the identity of "artist", the "artist" halo that I finally built up gradually disappeared.

But one thing deserves a follow-up note. One day, a girl who studied art in the Academy of Fine Arts approached me and said that her graduation thesis was about the living conditions of young artists. After reading the article I wrote, she liked it and wanted to interview me.

It was an interesting experience to swap roles with an artist. It just so happened that she also asked a question about her identity that day, "Why do you think you are not an artist?"

In her opinion, the Academy of Fine Arts will not teach you how to be an artist, as long as you think you are an artist, then you are. But I don't seem to have that kind of psychological identity, and I said, "Maybe because I don't belong to that circle, and I don't really want to fit in. And I don't think I have to be an artist before I can do something like this."

However, I will not deliberately deny it, "Because at the site of the exhibition, if I explained that I was not a photographer or an artist every time, others would ask again, then why do you want to hold an exhibition? So I think now, An 'artist' is just an identity in a social relationship. Today I am holding an exhibition, so my identity is the artist, and their identity is the audience."

Answering the reporter's question turned out to be like this. Unlike before, where I was always careful to hide my personality, on that day, I knew I had room to express my opinion whether the other person agreed with me or not. And I'm also curious about what I see from someone else's point of view. But at the same time, I finally realized the insecurity of being an interviewee, as if a part of my right to explain had been taken away from me.

So although I was happy to share my thoughts with her and didn't care how she would use the material in her thesis, when she said before leaving that she might print the paper and sell it in some art fairs in the future, I Instinctively, like all "troubling" interviewees, he asked: "Can I see it before printing?"

Before the Titanic sank, we were still pawns in Vanity Fair

In my observation of how interviewers and artists interact, aside from media production, I most often contrast our roles with the relationship of anthropologists to their subjects.

In an anthropological ethnography I recently read, "Why the Suya Sing," the author wrote:

"Anthropologists are increasingly being asked a question by those in the societies they study: 'What can you do for us?' , because it signals the end of certain forms of colonial control. The Suyas never asked us that question, probably in part because they knew what we could do for them. We could be 'their whites' and bring them what they wanted things, treat patients, answer some questions about the world, and sing to them.”

This made me realize that the book I am reading was not born based on the principles of objectivity and neutrality, but based on an exchange, exchanging the civilizational achievements of developed countries for the primitive culture in the tribe. Compared to this apparently unequal relationship, it's hard for me to tell which way the balance of power is tilted between interviewer and artist. Most of the time, there is no absolute privilege between us, but more of a delicate consensus.

One scene that comes to mind often is the last moment in Titanic, before the ship sank, with three musicians still insisting on playing the final piece in the midst of a panicked crowd. For a long time afterwards, this was my most romantic fantasy of the artist. Sometimes I'm in the camera's perspective, sometimes the musicians. This is not a contradiction, because we are witnesses to each other no matter what.

But the achievement of such a consensus relationship is a matter of luck rather than the norm. When I was in college, once I couldn't resist the urge to take on difficult tasks, so I went to express my willingness to interview with a band that had long been the finale of major music festivals in China. Their agent came over, politely asked me to add him on WeChat first, and then locked me out of the lounge. I followed up on the possibility of an interview later, but he did not reply.

A young and feisty friend who went with me that day felt bad for me, "Why are you playing such a big name?!" But I wasn't that angry, at most a little frustrated. Especially now, I have stopped being so reckless to contact some artists who are "difficult to talk to at first sight", and I have learned to reject other people I don't want to interview in the same polite way. I carefully select the interviewees who are "well-matched" with me, sometimes referring to young people who are similar, sometimes referring to common topics, sometimes recommended by friends.

How can you find a balance between being alert and not overly harsh? Or how to respond to the dilemma brought by art in an artistic way? This is a question I've been trying to answer recently, and it's also a question about how to know yourself. It seems that people who yearn for art are ahead of ordinary people in most things. Only one thing is half a beat, and that is how to accept that before the sinking of the Titanic, we were still pawns in Vanity Fair.

(Photos are provided by the author, please refer to www.siqi.love for more information)

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More