About On Design Thinking

Gainesville is a mid-sized city in north central Florida. It has a subtropical climate and the city is beautiful: the streets are lined with black oaks, fragrant maples, etc., and the buildings are covered with Spanish moss. The city is also very poor. Nearly 34 percent of the city's 134,000 residents live below the federal poverty line -- more than double the national average -- and 57 percent struggle to meet basic needs. The University of Florida in Gainesville enrolls more than 50,000 students each year, but graduates tend to leave the city after completing their degrees. They go to other parts of Florida, or to other states where the opportunity seems to be greater.

In 2013, Gainesville elected Ed Braddy as mayor with a promise to change the economic outlook. Gainesville needs to be "a more competitive place for new businesses and talent," Brady said. Greater "competitiveness", he believed, would spur economic activity, keep graduates in the city, and create what Richard Florida called a "creative class." To achieve this vision, the Brady and Gainesville City Council appointed the Blue Ribbon Committee on Economic Competitiveness . Committee members traveled to Silicon Valley to visit the legendary Palo Alto consulting firm IDEO. After speaking with the leaders of IDEO, they hired the company to design Gainesville's metamorphosis.

IDEO is not a management consulting firm like McKinsey or Deloitte. This is a design consultancy - it believes that "design" is not only the discipline of envisioning physical and digital products, but also the discipline of transforming services and institutions . For more than eight weeks in late 2015, a team of IDEO designers took over a storefront in downtown Gainesville, where they interviewed hundreds of city residents. They design and test solutions to municipal problems. Finally, in collaboration with the Blue Ribbon Committee, the IDEO team released a report. The aim is to address what Mayor Brady has diagnosed as a lack of "competitiveness" in new businesses and talent.

IDEO's Gainesville Blue Ribbon Report is an upbeat document. Its homepage uses desaturated colors: grayish yellow, dark orange, muted brown. But when the report revealed its solution, its color suddenly came alive. "Today, the world runs on ideas," one headline declared. "We have one. We think it's a really good option." The idea is to make Gainesville "the most people-oriented city in the world."

How to make a city "citizen-centered" ? The IDEO report proposes nine revisions for Gainesville. The first was a rebrand: a new logotype, tagline and visual style. Another is to create a "Department of Doing," an office that helps people start or grow a business in Gainesville. Finally, the report says, the city should become more design-conscious. Urban employees should develop “design thinking”: using design methods to solve problems. It should replace city council subcommittees with design thinking workshops and frame policy issues as design issues.

The Gainesville City Council accepted the blue ribbon report. So does the media. In 2016, Fast Company published a long feature article titled " How One Florida City Is Reinventing Itself With UX Design ."

Following the release of the report, city commissioners selected Anthony Lyons, the director of the Blue Ribbon Commission, who has worked closely with IDEO, as city manager. Lyons was in charge on an interim and then a long-term basis, overseeing more than a thousand city employees and the general fund budget. He obtained the resources needed to implement IDEO recommendations.

Design is a talisman with almost infinite meanings. Design is fashion design, urban design, and graphic design and product design; it is also analytical design (biology), object-oriented design (computer science), intelligent design (creationism), etc. Some of these uses seem to have little in common. Design, however, does revolve around certain ideas: intent, planning, aesthetics, method, vocation. Together, these ideas form a social system that produces meaning, defining the boundaries of knowledge and the location of cultural and economic values. In other words, design and the ideas associated with it constitute a discourse.

That is: they are historic. Even in English, design doesn't always mean what it means now. The term was used to refer to most visual arts until the end of the 19th century. But later, that statement changed. In the early 20th century, design began to refer to the visual styling of existing products. Then, as modernist ideas spread in Europe before World War II and Americans embraced the idea of "industrial design," design began to refer not only to styling a product, but also to conceiving and planning its function. That's when design started to make sense, as Steve Jobs would later put it, "not just what it looks like and feels like," how it works".

Design now means something broader. Around the time of World War II, design began to mean making things that "solve problems." With the influence of global social movements and the rise of digital technology in the mid-20th century, it began to mean making things that are "people-centric." Lately, design doesn't require making things at all. It can just be a way of thinking.

Of all these developments, the idea of design as a broadly applicable way of thinking - the idea of "design thinking" - is probably the most influential. The broader category of "design" can be found everywhere—ads, TV, podcasts, and blogs. But "design thinking" has also reached the halls of power. You can find it in the upper echelons of corporations, governments, and universities. It organizes and coordinates the decisions of managers and elites. As Robert Sutton puts it, at Stanford's d.school, "design thinking" is often seen as "a religion, not a set of practices that inspire creativity" (more like a religion than a set of practices for sparking creativity). So what is design ?

This question is urgent for me, mainly because I have been trying to discuss "design thinking" with design students. I am an interaction designer. I work in a studio that makes digital tools for corporate clients. I also teach a graduate course on digital design and design studies. I try to teach some practical skills - interviewing, sketching, wireframing, prototyping, usability testing - and some theory. But there seems to be a need to discuss "design thinking" lately too, as my students are asked to discuss it in job interviews and then in their jobs.

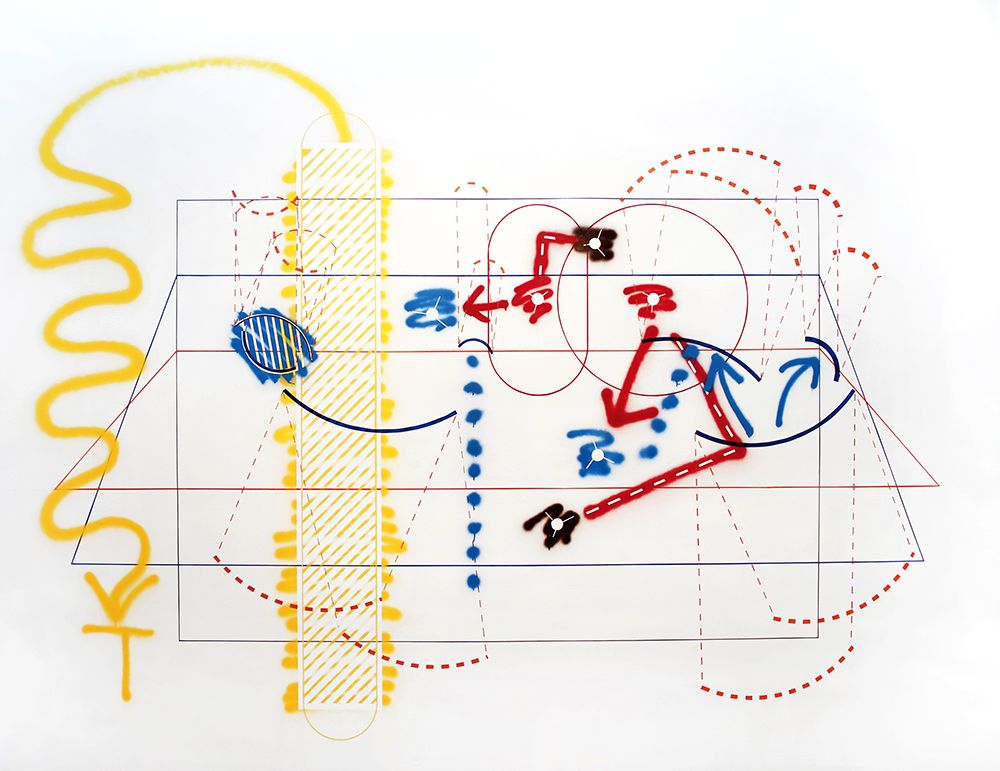

By "design thinking" I mean: using a particular set of design methods to solve problems that traditionally have fallen outside the purview of design . I show my students what designers call the "hexagon diagram," a ubiquitous image from Stanford's d.school designed to represent the five steps of design thinking. It consists of five hexagons: "Empathize", "Define", "Ideate", "Prototype" and "Test" . The idea is that design thinking involves listening and empathy, and then using what you hear to define the problem you want to solve. Then come up with ideas, prototype those ideas, and test those prototypes to see if they work.

This is a simple and easy to understand diagram. My students see Design Thinking as an easy-to-understand approach to problem solving. They are also optimistic. They read that design thinking has been applied in fields as diverse as education, health, government, and corporate culture transformation. Design thinkers are easier to hire, more useful, and more valuable. Suddenly, everything was a design thinking problem: postpartum depression, racism in sentencing, unsustainable growth.

To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail. But my students are not stupid; they are smart. They found something. In the world they inhabit, "Better by design" is a dominant construct of feeling.

Design has been a profession in America since the 1930s. When consumer purchasing power collapsed during the Great Recession, manufacturers embraced "industrial design," hoping that injecting artistic elements into consumer products would attract more people to buy. In 1946, designers convened a "Conference on Industrial Design, A New Profession" at the Museum of Modern Art to discuss the standards, pledges, and educational requirements their new craft might adopt.

But the story of design thinking itself—and how design reached its deification as a "floating signifier," detached from any one object, medium, or output —begins with World War II. As the war began, American industrial designers moved into government jobs. They designed everything for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, from liquid-propellant rockets to molded plywood cleats to a pair of strategy chambers and a giant spinning globe. They let their collaborators—scientists, mathematicians, engineers, and others in industry, academia, and government—recognize that designers are all-around architects of smart solutions across domains .

After the war, as their collaborators returned to their respective industries, so did the reach of design—as the word implies. Industrial designers get more jobs. Graphic design is considered an independent art. More general "design conferences" emerged - conferences that focused not on a single subdiscipline (industrial design, fashion design, architecture), but on a unified practice of new design concepts. The Aspen International Design Conference , founded in 1951 by Walter Paepcke and Herbert Bayer , is a good example. Paepcke, president of the Container Corporation of America, believes the US is in a "new era" where "the influence of designers and their consultants permeates the entire organization." The Aspen Conference became an annual event attended by renowned architects, industrial and graphic designers, as well as Gloria Steinem, C. Wright Mills . Wright Mills, Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, Susan Sontag and Gwendolyn Brooks. "Design" has become more than just a series of occupations, but a broadly related area of focus.

Broadening the scope of design is the first step in establishing “design thinking,” which relies on expansive spaces. The next step is to increase self-awareness and realize what this new ability means. In the two decades after the war, American and British intellectuals began to question what design was. What does this word mean? What counts as design and what doesn't? How is design different from other ways of thinking and cognition? Is it just planning? Planning by a professional planner, or planning like everyone does every day?

Design is all sorts of critical voices discussing a problem around an uncharted territory until it forms itself or doesn't form some kind of solution. (Design was a multiplicity of critical voices batting a problem around unknown terrain until it formed itself, or not, into some kind of resolution.)

The mid-20th century systems scientist C. West Churchman was the midwife devised for a new sense of self. Churchman West was Quaker-educated in Philadelphia and holds a Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Pennsylvania, joining the department as an assistant professor in 1939. His doctoral research focused on a branch of logic called propositional calculus. When the U.S. was preparing to enter the war, West Churchman found a more specific and practical job at the U.S. Ordnance Laboratory at the Frankfurt Armory in Philadelphia. The Frankfurt Armory is a huge, coordinated, modern place with a workforce of soldiers and civilians. Its purpose is to design, manufacture and test ammunition. West Churchman became head of the mathematics department, where he tackled problems of statistical quality control. He also devised experimental methods for testing small arms ammunition in the arsenal.

After the war, West Churchman left the Frankfurt Armory, but he never returned to fully abstract academic work. Instead, he turned to the new field of operations research: the study of applying scientific methods to decision-making, especially in corporations and other institutions. He became interested in design. Specifically, he studies the design of social institutions that may improve the human condition. He wondered if everyone was designing -- everyone was planning the future, wasn't it? — or whether design should be considered a specialized discipline.

In 1958, West Churchman became a professor at the UC Berkeley School of Business Administration. At Berkeley, West Churchman began weekly faculty and student workshops in the brand-new Barrows Hall dedicated to understanding design and design methods. Colleagues call it the "West Churchman Symposium." It was premised on the premise that "design is an activity that almost everyone practices, at least some of the time, and there may be some generalizable observations about how people do it," one participant later recalled.

How do people design? In 1962, the first design method conference was held in London, and West Churchman and his colleagues became increasingly interested in the question. At the conference and at the "West Churchman Symposium," the mood was upbeat. In 1964, Berkeley architect and design theorist Christopher Alexander published a small book , Notes on the Synthesis of Form , which argued that because design problems were complex, they should be Simplify to solve. Alexander writes that the design is neither mysterious nor intuitive. It's more like math: as mathematicians do when calculating the seventh root of a fifty-digit number, designers should simply write a problem down and break it down into smaller problems. These problems can then be reorganized into sets, subsets, and patterns that point to the right solution.

It was the early '60s: the height of this naive confidence. Alexander, West Churchman and their "methodologist" colleagues - designer John Chris Jones; engineer and design researcher L. Bruce Archer; economist, psychologist Scientist and political scientist Herbert Simon — both believe that the design process can be fully catalogued, described, and rationalized. (Simon, who later won the Nobel Prize in Economics, argued that all designs are problem-solving and can be reproduced as computer programs.)

Then Horst Rittel walked into the West Churchman Symposium. Born in 1930 and raised in Berlin, Ritter came to Berkeley from a German design school that originated in the Bauhaus, the Ulm School of Design, an internationally renowned school that was then Its teachers are divided by serious political divisions. He always wears a suit. Like most seminar members, he also lived through World War II. But he saw it from the other side. He had a different understanding of the postwar turn to rational methods.

Ritter is also fundamentally interested in why and how people design. But that's what he has in common with the rest of the group. Unlike other workshop members, Ritter is not optimistic about rationalizing anyone's design or planning process, or making it a method.

In 1967, the paper that Ritter read at the "West Churchman Symposium" was not primarily about design methods, but about design issues: issues that Ritter believed should be the scope of design, from poverty to the need for sewerage. Ritter put such questions in the context of the unfolding history of the 1960s, where, as he wrote, the single concept of the "American way of life" was "concession," and individuals had reason to question the power of the professional class to make decisions on their behalf. .

What ties these issues together, Ritter said, is the fact that the actual problem is always uncertain. In other words, it's hard to say if you're diagnosing the problem correctly, because if you dig deeper -- why does this problem arise? - You can always find more fundamental reasons than you say. There are also no right or wrong answers to these questions, only better or worse solutions. In fact, they are not like math problems. There is no authoritative test of the solution, and no evidence. More effort will not necessarily lead to better results.

There are other aspects of these problems that are not like mathematics. Ritter and his colleague Melvin M. Webber wrote in publishing Ritter's report as a paper that they were inherently high-risk. Any implemented solution leaves "traces" that cannot be removed. They write: "It is impossible to build a highway to see how it works, and then easily fix it after unsatisfactory performance, large public works are virtually irreversible, and they have consequences that Very long half-life." Designers have no "right to be wrong" because these issues matter.

Ritter called it a "wicked problem." They are "evil" not because they are immoral or evil, but because they are malicious, hopeless and callous. There are indeed some simple problems that don't rise to this level. But "now that the relatively easy problems are solved", those that are worth the designer's time are the worst. The most thorny problems in heterogeneous social life require the high concentration of designers.

For Ritter, the evil of design problems means they can never be solved by a single resolution process. There cannot be a "way". For example, textbooks tend to break down engineering work into "phases": "Gather information," "Synthesize information and wait for a creative leap," and so on. But for evil, Ritter writes, "this scheme doesn't work." Understanding the problem requires understanding its context. It is impossible to gather all the information before starting to develop a solution. Nothing is linear or consistent; designers don't and can't think that way. If there is any description of the design process, it is as a parameter. Design is all sorts of critical voices discussing a problem around an uncharted territory until it forms itself or doesn't form some kind of solution.

Ritter believes this approach is a wonderful thing. He later wrote that this meant an "awe-inspiring cognitive freedom" without the protection of algorithms and rules of validity. "Living in cognitive freedom is not easy," he writes, so designers often look for sachzwang -- practical constraints, inherent inevitability, "a way to 'ought' from facts." . But they shouldn't. Without methodological constraints, there is room for heterogeneity in design. It has the ability to surprise. "Nothing has to stay the way it is," Ritter wrote, "or so it seems."

For those of Ritter's colleagues who have been working to identify and systematize a true approach to design, this cognitive freedom is especially hard to bear. Ritter's uncompromising, rigorous, dispassionate voice of academic rejection, combined with the hopelessly political and social conflicts of the 1960s, helped put an end to the rationalist project. John Chris Jones , who co-hosted the first design method conference in London in 1962, is now "against design method", in his words. Christopher Alexander rejected his own methodological work, including The Synthesis of Forms. "Forget it, I would say," he wrote in 1971, "forget everything."

Ritter set his sights high. Design should solve the most difficult problems facing civilization. In helping his peers embrace this view, he has begun, albeit quietly, to expand the scope of the discourse on design. At the same time, he believes every designer should approach this massive project differently. Precisely because the problem is complex, there is no one way to do it.

In 1971, before Ritter and Weber's full article was published, Austrian-American designer Victor Papanek published a book that began to push these claims into public discourse. Design for the Real World, now dubbed "one of the world's most-read design books" by its publishers, cautions designers to only solve complex problems: ecological issues, for example Disaster, not "mass leisure and fake fashion". Papanek agrees that trying to extract reproducible methods from design—developing "rules, taxonomies, taxonomies, and procedural design systems"—is foolishness.

Capaciousness leads to self-awareness. Now, self-awareness produces a consensus that competence precludes either approach. In 1987, Peter Rowe published an ethnographic study of designers called Design Thinking . But Rowe's study of the observed evidence has concluded, as Ritter and Papanek argue, that, in fact, there is no such thing as "design thinking" at all. "Instead," Rowe writes, "there are many different decision-making styles, each with their own quirks and manifestations of common traits." There is no set approach to design, which has become commonplace. The more interesting question is how to observe and negotiate the proliferation of differences.

In 1978, David Kelley, a 27-year-old electrical engineer from Ohio, completed a master's degree in product design at Stanford University and started a design studio with a classmate. They set up shop above a clothing store in Palo Alto and hired four friends from graduate school. Former professors started sending clients over. Kelly's breakthrough came when someone introduced Kelly to Steve Jobs, who asked him to design the mouse for the new Apple Lisa computer. Kelly wondered what a "mouse" was. He made the first prototype with a butter dish and a rolling ball. "We would ask," he recalls, "should you slide the mouse with your fingertips, or slide the mouse like you slide a bar of soap?" The company-designed mechanism is still in use. In 1991, Kelly Designs — whose co-founder has since left — merged with the company owned by Bill Moggridge and visual designer Mike Nuttall . Bill Morgridge designed the first laptop. After a company-wide competition, they named the new company IDEO: a phrase, Kelly later recalled, that resonated to a degree because it sounded like idea and ideology.

IDEO was born in the new Silicon Valley. Its members are industrial designers: people who design physical products with both beauty and function in mind. They were also "interaction designers" — a term Morgridge coined himself — who used the new science of "human factors" to design interactions between human and machine interfaces. Given their expertise in industry, interaction design, and engineering, there's a good chance they'll get a job designing something Silicon Valley and friends have just discovered they need. By the early 2000s, the company had developed thousands of products, most of which connected the physical and digital worlds. It reportedly has revenue in the tens of millions of pounds and has opened new studios in Munich, Tokyo and Milan.

When the dotcom bubble burst, revenue fell. IDEO relies heavily on Internet start-up customers, and more on customers' confidence in the future. What should I do? In 2003, David Kelly had an epiphany: why not reinvent what they already did? Why be "the guy who designs the new chair or the car," Kelly later recalled to Fast Company magazine -- or, in fact, a software interface -- when would he become a "methodologist"? Suddenly, Kelly said, "it all made sense." They will no longer call IDEO's approach "design." Instead, they'll call it "design thinking."

It's designed for the service economy: memorable, marketable, repeatable, apparently generic, and a little fuzzy on the details. (It was design for a service economy: memorable, saleable, repeatable, apparently universal, and slightly vague in the details.)

"I'm not a person who likes words," Kelly points out, "but this is the most powerful moment in my life to create words or labels." Kelly was unfamiliar with the methodologies of early designers and design theorists. and disappointment in methodological expertise. But he knows his bottom line, and he knows his market.

Both professors and corporate "thought leaders" tell me that if you want to win big in life, you should create a memorable idiom. Design thinking proved to be a memorable idiom. It's "design thinking" that makes IDEO the most famous design company in the world. This gave David Kelly the clout to start the d.school at Stanford. It is this ideology that has driven thousands of people around the world to join the OpenIDEO community, organizing volunteer chapters in 30 cities and organizing events around IDEO's visionary Design Thinking Challenge. It also contributes to the weird magic that IDEO seems to be in control of the design world. "I've been a professional designer for almost 20 years," Jake Knapp, a respected former Google Ventures designer, recently wrote, "I've always been obsessed with IDEO. What's going on inside? How does it work?" I attended several conferences at IDEO's Cambridge, Massachusetts studio a few years ago, and as an ambitious designer at the time, I was proud and in awe. This is ridiculous: IDEO is just another multinational company. But this is a multinational company whose niche branding and marketing, funded by the success of "design thinking", have achieved such phenomenal success that it seems like straight magic.

Proponents of design thinking do not define it very clearly. "In short," IDEO CEO Tim Brown wrote in the Harvard Business Review in 2008, "it's a process that uses a designer's sensibility and approach to connect people's needs with Matching technically feasible and viable business strategies that translate into customer value and market opportunities.” Of course, it’s not as “simple” as one might hope.

But the story of design thinking in practice is clear enough. Healthcare organization Kaiser Permanente hired IDEO to address the issue of Kaiser nurses losing vital patient information during their shifts. Through a series of workshops in which participants roughly understood the nurse's experience, defined the problem, envisioned possible solutions, prototyped and tested it, IDEO and Kaiser defined a new shift process: To prevent the loss of important information, nurses This information will be delivered in front of the patient.

Another example: In 2006, the Colombian Ministry of Defense approached Lowe-SSP3, a Bogota-based advertising agency, in an attempt to persuade guerrillas from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) to disband. The agency follows the hexagonal approach. They conducted in-depth interviews ("empathy") with former guerrillas. They found that what fighters miss most as they mobilize are their families. The agency then developed a prototype and launched a campaign in 2010 called Action Christmas. Ten huge jungle trees, each close to a guerrilla stronghold, are hung with 2,000 motion-sensing Christmas lights and banners that read "If Christmas can come to the jungle, you can go home. Disband. Anything is possible at Christmas." The movement -- and a series of operations over the next three years -- is credited with prompting the disbandment of many guerrillas. (Other factors are certainly driving this trend.)

To be a design thinker, then, is to see hospital shifts and guerrilla warfare as design problems. To see "design", whatever the word might mean, applies to just about anything. But even as "design thinking" makes "design" more expansive, it discards the self-conscious skepticism of "methodology" of designers after Horst Rittel in the 1960s. Design thinking is undoubtedly a recipe, a formula, a five-step process. The story of Caesar and Columbia is a definite and neatly linear process, a journey from one colored hexagon to the next.

It's designed for the service economy: memorable, marketable, repeatable, apparently generic, and a little fuzzy on the details. Horst Rittel has convincingly described the folly of trying to define or rationalize the "way" of design; IDEO's Design Thinking template brings that "way" back.

So in America in the early 2000s, design was again not just a method, but a general method—a method that seemed a little bit magical. It works for everything, anyone can do it. "Contrary to popular belief," Brown wrote in a 2008 Harvard Business Review article, "you don't need weird shoes or a black turtleneck to be a design thinker." In fact, you No need to be a designer. All you need is a set of designer qualities -- empathy, "holistic thinking," optimism, experimentalism, a collaborative nature -- and that colorful five-step map.

In previous years, IDEO would give everyone a self-paced video course to learn design thinking. (The current course is "Insights for Innovation": five weeks of online learning, $499.) Stanford's d.school has begun offering "design thinking boot camps" for executive education (the four days will take about 12, $600.) A New York Times columnist commented: “The design process can be effectively applied to ideas outside of traditional settings, sparking an explosion of activity, from using design as a medium for intellectual inquiry, to Ingenious solutions to serious social problems like homelessness and unemployment.” Meanwhile, the Chronicle of Higher Education headline asked, “Is Design Thinking the New Liberal Arts?” ( Is 'Design Thinking' the New Liberal Arts?)

In Gainesville, city manager Anthony Lyons spent three years on a design-driven transformation. Fifty city employees were trained in design thinking. The city opened a new "Department of Doing". The city's website has been completely revamped. Gainesville changed its logo and branding with the help of a local branding agency.

There are other successes. Anthony Lyons' move strengthens the city's relationship with the University of Florida, which officially partnered with Lyons in 2017 to make Gainesville "the new American city."

But there is also resistance. In June 2017, Paul Folkers, one of Gainesville's two assistant city managers, resigned without warning. Within a week, Lyons had replaced him with Dan Hoffman, the former chief innovation officer of Montgomery County, Maryland. That same month, the local NAACP (NAACP) filed a lawsuit against Lyons on behalf of city employees, alleging that Lyons "fired qualified professional public administrators because they questioned his conduct, according to his They served him as he wished.” He forced employees to resign, did not promote qualified city employees, and hired people — many of whom were “millennials” — from outside the city with less experience, the indictment said. Applicants from within Gainesville. Human resources director Cheryl McBride, who also resigned, filed an overlapping complaint with the city's Office of Equal Opportunity.

The city responded to the NAACP complaint with an investigation into Gainesville's hiring practices. The investigation did not find that Lyons created a hostile work environment. The investigation did find, however, that Lyons' team avoided or violated Gainesville's policies in various recruiting activities. But many more left.

Gainesville is one of the poorest cities in America and one of the most unequally distributed of income and resources. Black residents, who make up 22 percent of the city's population, live primarily in East Gainesville, where residents report woefully undersupplied grocery stores, inadequate transportation and poorly lit streets. Black residents of Gainesville had an average household income of $26,561, just over 50% of the median non-Hispanic white household income. Black residents have an 18 percent lower high school graduation rate than white residents. The unemployment rate for black residents is almost 2.5 times that of white residents.

Lyons and IDEO's design-driven project aims to address the so-called "competitiveness" deficit. As mentioned, this problem — and the changes Gainesville has made to address it, including a beautiful image design, better web resources, and what’s known as the “Department of Doing” The new office - has a nuanced relationship at best with the experience of many of Gainesville's poor and black residents. While these programs were designed to boost Gainesville's economy in general, they did not create affordable housing or increase high school graduation rates. They don't mention those who think "competitiveness" is a distant issue. They seem to leave a lot of Gainesville behind.

Lyons' resignation marks the end of the Gainesville design experiment. The mayor choked up as he said a public goodbye to Lyons; the head of the Gainesville Community Renewal Agency praised Lyons for his "bold" idea. Others are less convinced. "Gainesville is not a Silicon Valley startup," one resident told the Alligator, a newspaper at the University of Florida. "Looking good in a magazine is not really a sign of success."

I don't think Gainesville's design experiment has done irreparable damage to the city. I do think it promises a lot more than it can deliver. Horst Rittel reminds us that behind most problems ("competitiveness") lie worse problems. "Design thinking" cannot solve the evil problems that cause inequality in Gainesville: poverty, income disparity, structural racism, environmental injustice, unregulated market capitalism. You face evil problems by fighting them, not by solving them.

Horst Rittel argues that, in fact, design can encompass all of these: it can mean that, on a really complex problem, one strives to solve the problem in an honest and collaborative way. Anyone can take part in such a battle. But there's no one way to do it, and there's no guarantee it will work.

This is where design thinking worries me: it's a huge and tantalizing promise. Early on, Anglo-Americans fashioned design—the love of industrial design began during the Great Depression—but its claims and results were relatively modest. This recent fad of design thinking seems more insidious because it promises more. It promises a creative and enjoyable way out of difficulty, a jump from sticky notes to innovative solutions.

still have a question. By embracing "design thinking," we boil design down to an advanced epistemology: a better way of knowing and "solving" than the old, local, blue-collar, municipal, union, and customary ways.

Just as the Great Recession made industrial design the solution to the woes of American manufacturing, the bursting of the dot-com bubble of 2000-2002 and the recession of 2008, with their long tail effects, led to a new embrace and imagination of design New extension of jurisdiction. The specific concern this time is that everyone will face the knowledge economy.

But design is not magic. To solve a wicked problem, you have to get to its source—and to get to it, there is no hexagon diagram. Stop "lack of competitiveness," and you get a very neat solution because it doesn't touch on the underlying causes of Gainesville's economic stagnation.

There is no consensus on how to allocate resources, how to arrange social life, and how to achieve justice. Design, really design, is about acknowledging those differences - and then listening to your way, and pushing your way, to a new place. Ritter believes that this kind of fighting from different positions may be really evil, but rather than mask indecision with optimism, it is better to fight. He was right. Design may be an elegant package, but it doesn't always make things better.

Compiled from: MAGGIE GRAM - On Design Thinking

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!