Socialist Cybernetics in Chile: A History of the Cybersyn Project

Abstract: This paper presents the history of the Cybersyn Project , an early computer network developed in Chile during the socialist presidency of Salvador Allende (1970-1973) to regulate constant Growing the social property sector and managing the transition of the Chilean economy from capitalism to socialism. Under the guidance of British cybernetics expert Stafford Beer, known as the "father of managerial cybernetics", an interdisciplinary Chilean team devised a cybernetic model of state-owned factories and created a A network for the rapid transmission of economic data between governments and factories. This article describes the construction of this unorthodox system, examines how its structure reflects the socialist ideology of the Allende government, and documents the technology's contribution to the Allende government.

On November 12, 1971, British cybernetics expert Stafford Beer met with Chilean President Salvador Allende to discuss building an unprecedented tool for economic management. For Bill, this meeting is the most important; the project needs the president's support. Over the past ten days, Bill and a small team in Chile have developed a plan for a new technology system capable of aligning Chile's economic transformation with the principles of socialism under Allende's presidency. The project, later known as Cybersyn in English and "Synco" in Spanish, linked every company in the expanding state sector of the economy to a central computer in San Diego, allowing the government to quickly grasp production conditions and react to economic crises in real time. Although Allende was briefed on the project ahead of time, Bill was tasked with explaining the system to the president and convincing him that the project needed government support.

Bill walked to the presidential palace in La Moneda, accompanied only by his translator, a former Chilean naval officer named Roberto Canete , while his colleague was in the street Waiting anxiously in the bar of a hotel opposite. "A cynic might say, 'I'm letting it run its course,'" Bill later commented. "I accepted the arrangement and thought it was one of the most confident performances I've ever accepted; because I was able to speak my mind." The meeting went fairly smoothly. Sitting face to face (with Carnett in the middle, carefully whispering translations in their ears), Bill begins to explain his work on "management cybernetics ," the field he was working on in the early 1950s created and developed in his later writings. At the heart of Bill's research is the "viable system model ," a five-layered structure based on the human nervous system that Bill believes is present in all stable tissues—biological, mechanical and social. Allende, who had previously trained in pathology, immediately grasped the biological inspiration behind Bill's cybernetic model, nodding consciously throughout the explanation. This response has impressed cybernetic experts. "I explained the whole plan and the whole survivability system model in one fell swoop...I've never worked with anyone at the top who understood me."

Bill acknowledged the difficulties of achieving real-time economic control, but he stressed that a system based on cybernetic principles could achieve technological feats considered impossible in developed countries, even with Chile's limited technological resources. Once Allende became familiar with the mechanics of the Bill model, he began to emphasize the political aspects of the project, insisting that the system operates in a "decentralized, worker-involved and anti-bureaucratic manner." When Bill finally spoke about the highest level of the system, the place in Bill's model had been reserved for Allende himself, and the president leaned back in his chair and said, "Finally, it's the people (el pueblo [Spanish])." Allende With this phrase, De redefined the project to reflect his ideological belief that his political leadership equates to the rule of the people. By the end of the conversation, Bill had already got Allende to support the project.

On the surface, a meeting between a British cybernetic expert and a Chilean president (especially one as controversial as Allende) may seem unusual. The short-lived Unidad Popular (UP) government has arguably inspired historical scholarship more than any other period in Chilean history. Despite the extensive literature, little is known about the Chilean government's experiments in cybernetics during this period, nor about its contribution to the socialist experiments of the "People's Unity" government. Bill and Allende meet to write technology into Latin American history and reveal an unstudied side of the Chilean Revolution. To some extent, the construction of this system of documentation provides information on Chile's technological capabilities in the 1970s. More importantly, however, the project provides a window into the tensions within the Union of Peoples, Chile and the entire international community. The impressions and aspirations expressed by the participants of the various projects further reveal the alternative history of the era of "people's solidarity" based on technological optimism and the fusion of science and politics, bringing about social and economic change. This paper argues that experiments with "people's solidarity" using cybernetics and computation constitute another innovative but unexplored feature of Chile's democratic path to socialism. Therefore, studying this technical project promises to enrich our understanding of this complex moment in Chilean history.

In addition, knowledge of this technological enterprise contributes to enriching the literature on the history of science and technology, especially research on cybernetics and the history of computation. Bill and Allende's meeting showed that cybernetics is an interdisciplinary science covering "the entire field of communication theory, both in machines and in animals," a period that reached an important level in Chile, Allende's Chilean Revolution was open to these cybernetic ideas and their applications. However, most cybernetic discussions so far have focused on the evolution of these ideas and their application in the United States and Europe, rather than how they migrated to other parts of the world, such as Latin America. The history of Chile provides a clear example of how different geographic and political circumstances led to new expositions of cybernetic thought and innovative applications of computer technology, ultimately illustrating the importance of incorporating Latin American experiences into these academic institutions. This article will first explain how cybernetics came to Chile, caught the attention of the country's president, and guided the construction of this unique technological system.

From another perspective, Bill and Allende's meeting also illustrates the importance of technical soundness and political ideology in the construction of Cybersyn . Although the project is technically ambitious, it cannot simply be described as a technological endeavor to regulate the economy from the start. From the perspective of the project team members, this helped bring about Allende's socialist revolution -- "revolutionary computing" in the truest sense of the word. Moreover, the system must do so in a way that is ideologically consistent with Allende's politics. As this article will show, the tensions surrounding the design and construction of Cybersyn mirror the struggle between centralization and decentralization that plagued Allende's dream of democratic socialism. During Allende's presidency, Chile's political polarization strongly shaped perceptions of the project and its role in Chilean society. The interplay of cybernetic thought, Marxist thought, and computer technology found in this project illustrates how science and technology contributed to Chilean ideas of governance in the early 1970s and changed the possibilities of socialist transformation. Elaborating on this multifaceted relationship is the final focus of this paper and shows that technological research can expand our knowledge of the history and political processes of the Latin American region.

Chilean cybernetics

The origins of cybernetics are well documented elsewhere. Previous academic research has shown that cybernetics developed from a World War II project to create anti-aircraft servos that would allow weapons to precisely target the future location of enemy aircraft. This problem prompted Norbert Wiener, Julian Bigelow, and Arturo Rosenblueth to develop a feedback control theory that Predictive computation from incomplete sets of information later developed into a theory of self-correcting control, which many believe can be applied to machines and organisms. Attempts to draw a link between mechanics and biology arose as early as 1943, when Rosenbluth et al. wrote, "A unified behavioral analysis applies to both machines and organisms, regardless of the complexity of the behavior. ." This belief laid the foundation for cybernetics. Cybernetics is an emerging interdisciplinary science devoted to applying concepts from mathematics and engineering—such as statistical modeling, information theory, and feedback loops—to countless systems, including those outside the fields of mechanics and biology.

Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela provided the initial link between Chile and the cybernetic community, although Maturana never claimed to be an expert in cybernetics. Born in Chile in 1928, Maturana studied medicine at the University of Chile and later as a graduate student at Harvard University's Department of Biology. In 1959 he co-authored with Warren McCulloch, Jerome Lettvin and Walter Pitts the seminal paper "What the Frog's Eyes Tell the Frog's Brain" (What the frog's eye tells the frog's brain) , they are all important figures in the field of cybernetics. After completing his Ph.D., Maturana returned to Chile to take up a position in the Department of Biology, Universidad de Chile, Chile's most respected public university. Here, he continued his work on the optic nerve, but more broadly in an attempt to uncover the organization of living organisms. Varela began his studies under Maturana at the University of Chile and followed his mentor to pursue a PhD in biology at Harvard University. Like Maturana, he returned to Santiago and accepted a faculty position at the University of Chile. The title of the first book they co-authored, On Machines and Living Creatures, shows that the cybernetic perspective persists in their biological research. Here, the authors present their seminal theory of selforganising systems , the so-called autopoiesis .

However, their contributions to Chilean cybernetics in the 1960s and early 1970s did not go beyond the laboratory. At times, Maturana also advises Bill on the theory of the system, Bill knew of Madurana's work before Allende took power, and the two strengthened their ties during Bill's time in Chile. Maturana and Varela later gave several lectures to core members of the Cybersyn team, but they always did so in an unofficial capacity. Although these biologists built the first bridges between Chile and the international cybernetic community , they did not contribute to the familiarization and application of cybernetics to the Chilean government during Allende's presidency. Bill himself would inadvertently provide this connection.

This article is not a complete biography of Bill, but a brief synopsis will allow readers to appreciate the unorthodox nature of his character in business and cybernetics. Unlike many of his peers in cybernetics, Bill himself never received a formal degree; his service in the British Army during World War II interrupted his undergraduate studies in philosophy. After the war, Bill entered the steel industry and quickly rose to management. In 1950, a friend accidentally handed Bill a copy of Norbert Wiener's seminal book , Cybernetics . Reading the book changed Bill's life, prompting him to write an impassioned letter to the renowned MIT mathematician detailing his application of cybernetic principles to the steel industry. Wiener, unfamiliar with the business world and intrigued by new applications of his work, invited Bill to visit him at MIT. Bill eventually became an informal student of MIT biologist Warren McCulloch and a friend of Wiener and the University of Illinois electrical engineer Heinz Von Foerster. An independent thinker, Bill had presented a paper titled "The Irrelevance of Automation" at an international automation conference, an occasion that reportedly convinced von Forster in the UK People do have a sense of humor. An "old-fashioned leftist", Bill sought to use his understanding of cybernetic principles to effect social change, as evidenced by a series of lectures he gave between 1969 and 1973, which he later published Platform for Change . Bill, known for his long beard, alcohol in hand and smoking 30 cigars a day, fashioned, in the words of one reporter, something like "a hybrid of Orson Welles and Socrates" ” (cross between Orson Welles and Socrates) .

After many years as head of cybernetics and operations research at United Steel, the UK's largest steel company, Bill left the company to take the helm of a French consultancy, SIGMA, which integrated operations research ( SIGMA) . OR) techniques applied to business problems. Bill recalls that he tried to use operations research "to change industry and government by building mathematical models, the same way it changed the army, navy, and air force [during World War II]." Considering the numerous contributions that operations research made to the development of Allied anti-aircraft guns and submarines during the war, this was a rather ambitious goal.

SIGMA's reputation grew and the company gradually began to attract international clients. In 1962, the director of the Chilean steel industry asked SIGMA to provide its services. Bill refused to travel in person — he had never been to South America, and his busy schedule made long layovers unreasonable — but he organized a team of British and Spanish staff to travel to Chile in his stead. SIGMA's work in the steel industry gradually extends to railways. Due to the heavy workload, the Chilean SIGMA team often hires students to fill vacancies, including Fernando Flores , a young Chilean studying industrial engineering at the Catholic University of Santiago.

A workaholic by nature, Flores devoted himself to mastering the principles of cybernetics and operations research for SIGMA practice, and after reading Bill's Decision and Control and later Cybernetics and Management ( After Cybernetics and Management) , became familiar with Bill's work. His knowledge of operations research landed him a faculty position at the Catholic University, and by his 27th birthday he was acting dean of the engineering sciences department. Like many of his contemporaries, Flores was active in academia and politics. In 1969, a group of young intellectuals from Catholic universities, including Flores, broke away from the Christian Democratic party and established the Movement of Popular Unitary Action (MAPU) , a movement led by young intellectuals. A political party of members who are critical of the Christian Democrats and are allied with the Communist Party and the Socialists in the "People's Unity" coalition. The addition of the MAPU, combined with the incompetence of the right-wing and Christian Democrats, played a major role in Allende's narrow victory in the 1970 presidential election. In recognition of his political loyalty and technical ability, Allende's government appointed the then 28-year-old Flores as general technical manager of Chile's National Development Agency (CORFO) , which Allende had previously been responsible for nationalizing Chile's industry. national development agency. It is the third highest position in CORFO, the highest position held by a member of MAPU in the national development agency, and the management position most directly related to the day-to-day supervision of nationalized chemical plants.

Allende believed that the nationalization of major industries should be the highest priority, a task he later called "the first step toward the making of structural changes ." The nationalization effort will not only allow the Chilean people to restore foreign- and privately-owned industries, but will also “abolished the pillars that underpin the minority that have kept our country in a state of underdevelopment” — Allende said in the statement by A "monopoly" of industry controlled by a few Chilean families. The majority of the members of the "United Peoples" coalition believe that by changing Chile's economic base, they will be able to achieve institutional and ideological changes within the framework of Chile's original legal framework, which differentiates Chile's socialist path from other socialist countries.

After Allende took office in November 1970, the government used the first few months to implement policies based on structuralist economics and Keynesian "pump priming" by increasing purchasing power and employment. economic growth, thereby pulling the Chilean economy out of the recession that the Allende government took over. The start of the land reform program and government aid to rural workers increased the purchasing power of individuals in the poor agricultural sector, while real wages for Chilean factory workers rose by an average of 30 percent during Allende's first year in power. Initially, these efforts to redistribute income succeeded in enabling more and more people to have money to spend, stimulating the economy, increasing demand, boosting production, and expanding the popular base supporting the People's Solidarity coalition. In the government's first year in office, GDP grew by 7.7%, production by 13.7% and consumption levels by 11.6%. However, these economic policies will soon come back to haunt the "People's Unity" government in the form of inflation and massive consumption shortages.

On the production side, the government wasted no time in expanding the existing state sector and taking it to a new level. By the end of 1971, the government had transferred all major mining companies and 68 other private companies from the private sector to the public sector. The rapid pace of the government's nationalization program, coupled with the lack of a clear, consistent structure and boundaries, has heightened concerns and insecurities among Chilean SME owners. Moreover, the promise of social change helped to spark a revolution from below, in which workers sometimes seized control of factories against the express wishes of their compañero presidente. Less than a quarter of the companies confiscated during Allende's first year in office were on the government's list to be incorporated into the public sector.

The situation is further complicated by foreign investors in Chilean copper mines and telecommunications companies (eg, ITT) who oppose nationalization without adequate monetary compensation. In July 1971, estranged Christian Democrats accused the administration of abusing legislative loopholes to acquire desirable properties, introducing an amendment requiring Congress to approve all expropriations. They claim that the government invoked a law enacted during the Great Depression to prevent layoffs and factory closures as a means of nationalizing factories once workers aligned with the left began to strike and interrupt production. They proposed an amendment that would require Congress to pass a law approving every new plant acquisition, thereby curbing the pace of nationalization, a legislative move that would have greatly weakened Allende if the president did not question its legality executive powers.

In addition, the rapid growth of the nationalized sector quickly created a clumsy monster. The increase in the number of industries controlled by the state and the number of employees in each industry presents the government with the difficult task of managing an economic sector that is increasingly difficult to monitor. Under a decree passed in 1932, the government sent "interventors" to replace the previous management and regulate the activities of these newly nationalized industries. However, these representatives often create new problems. While many are competent and committed to their jobs, some are completely incompetent for these positions and some are corrupt. The problem of effectively managing the new "sphere of social property" was exacerbated by the decision to distribute appointments equally among political parties, regardless of the capabilities of their respective talent pools. Even parties within People's Unity criticized Allende's choice of "interventionists". For example, some Communist Party members believe that some "interventionists" simply replaced the previous managers, lived in similar houses, and drove similar cars. From the Communists' point of view, these representatives not only failed to provide adequate means to bring production under the control of the people, but they also helped to obscure the social reality of the continuing status quo. Day-to-day operations within the factory were further marred by political conflict over "interventionists" who saw themselves as representatives of the party. At times, workers in some businesses refused to listen to other party managers; this in turn led to frustrating party meetings and negotiating processes.

As the joy of the honeymoon period began to fade, the long-term instability of Allende's method became apparent. Politically motivated reforms, such as the income redistribution advocated by People's Unity, emphasize long-term structural transformation rather than short-term economic management. Consumption began to outpace production, inflation began to soar, and government deficit spending continued to grow, all exacerbated by dwindling foreign reserves and the denial of foreign credit. By July 1971, inflation had climbed 45.9 percent, and it would continue to rise to unprecedented levels under Allende's presidency. From a production point of view, the "people's solidarity" program for industrial expansion through mass hiring initially helped factories increase production and gain full production capacity, but once a certain production capacity was reached, the number of employees started Over the available workload, productivity begins to decline. Valenzuela's retrospective observation that "the economic crisis of the Allende era clearly became the main problem that the government could not solve" succinctly describes the extent of Chile's recession.

At the time, however, the government considered the economic situation far from "unsolvable". On July 13, 1971, Bill received a letter from Fernando Flores stating that he was familiar with Bill's work and "now able to implement scientific ideas about management and organization on a national scale. —In this context, cybernetic thinking becomes a necessity”. He asked Bill how to apply cybernetic principles to the management of the state sector. Bill's response was enthusiastic:

I have to ask you if I can play some roles, although I don't know what to suggest. Believe me, I am willing to give up any current employment contract I have for this opportunity. That's because I believe your country can really do it.

A month later, Flores flew to the UK to meet the man he had studied during his years working for SIGMA. The two met at the Bill's Club Athens pavilion in London. Flores doesn't speak much English and Bill doesn't speak any Spanish, but the two manage to communicate in French, English and Latin. Flores told Bill he had assembled a small government team and sent cybernetic experts to Chile to guide them in applying cybernetic principles to nationalization efforts. In November 1971, Bill arrived in San Diego.

Build Cybersyn

Bill arrived in Chile on the day Allende celebrated the first anniversary of his election. In front of a packed crowd at the National Stadium, the president told the crowd that now, "more than ever, people need to understand what life in Chile is and the path that truly belongs to us, the path to pluralism, democracy and freedom, which is open to The road to the gates of socialism." It was a speech full of celebration, promise and national pride that cheered the entire country. Shortly thereafter, the finance minister announced that Chile's annual borrowing had exceeded $100 million, far exceeding the projected inflow of $67 million this year.

During the ten-day visit, Bill met with various influential figures in the Chilean government, including Economy Minister Pedro Vuskovic and Allende himself. Flores assembled a carefully selected Chilean team and began working with Bill, including representatives from various disciplines. This sets the tone for the interdisciplinary collaboration required for the Cybersyn Project . Most of these early team members were friends of Flores. "It was very informal in the beginning, like most things. You seek support among your friends," Flores noted. Given his role as general technical manager at CORFO, one of the largest government agencies at the time, Flores Reis controls a huge amount of resources. Through the operation of CORFO, Flores was able to raise the funds needed to pay Bill $500 a day and to obtain other material and human resources needed for the project. Additionally, the CORFO connection gave Flores the ability to recruit people with expertise not found in his friendship network. Flores praised his leadership, boasting, "I don't need to convince others. Given the vast amount of resources I manage in every aspect of the economy, I have a lot of power to do so. With the Cybersyn Project ), we (CORFO) are so huge, it’s a small amount of money compared to who we are and what we’re at.” The former Cybersyn team member also highlighted how Flores’ personality played out during the project’s launch Importance, calling him a "slick operator" and "savvy dealer".

As Bill learned about Chile's economy and politics, each member of his team read the manuscript of his book , Brain of the Firm , and adopted Bill's managerial cybernetics as their lingua franca. The book outlines a "viable system model ," a system that Bill argues can describe stability in biological, mechanical, social, and political organizations. The design of Cybersyn cannot be understood without a basic understanding of the model that played a key role in the fusion of the politics of the Allende government and the design of this technological system.

The "viable system model" that first appeared in Brain of the Firm (1972) remains one of the guiding concepts behind Beer's work today. It is defined as "a system that survives. It is coherent; it is intact, but it still has mechanisms and opportunities to grow, learn, evolve and adapt" . The values of the system's "variables" (inputs) determine the final "state" of the system ; Bill refers to the number of possible states as the "variety" of the system, directly citing Ross Ashby 's important theory "Law of Requisite Variety" . A system is able to keep all key variables within the limits of the system's equilibrium, thus achieving "homeostasis" , a quality that all feasible systems aspire to achieve. Based on these principles, Bill constructed a five-layer model of a working system based on the human nervous system. Although the model has biological origins, Beer insists that abstract structures can be applied in many contexts, including corporations, economic enterprises, bodies and nations.

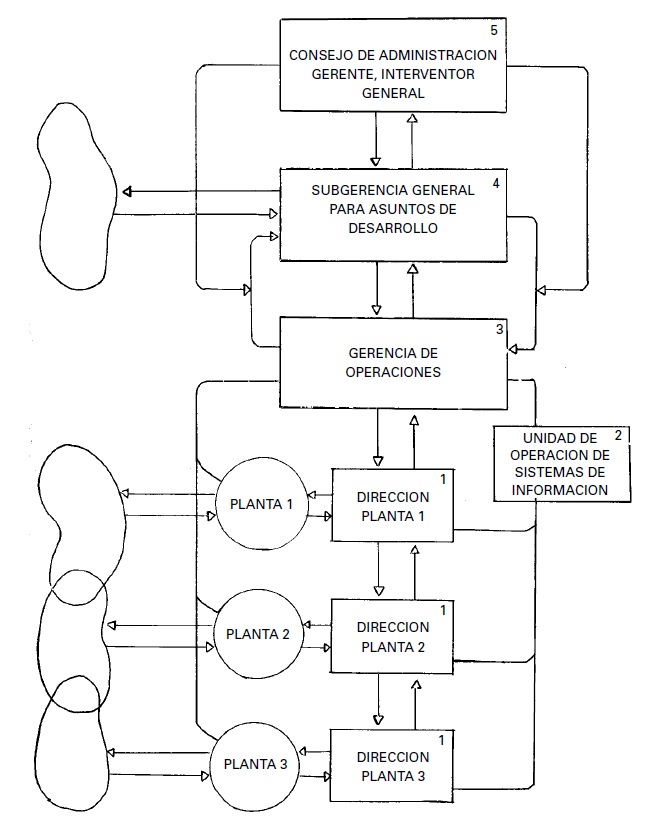

In its most basic form, the "viable system model" resembles a simple flowchart connecting the five levels of the system hierarchy. In his writings, however, Bill freely switches between metaphors from machines, organizations, and organisms when describing the purpose and function of each level. For the purpose of this paper, the “viable system model” is explained here only as applicable to the Chilean industrial sector, with a particular focus on the five-layer cybernetic mapping of Chilean firms in the social property domain (as shown in Figure 1). . It is perhaps easiest to understand the model at this level, although it should be remembered that the Cybersyn archetype was originally run within CORFO's governance structure , which is a higher hierarchy than the single enterprise model discussed here. Although Bill hopes to one day restructure corporate management to reflect this model, the hypothetical management chain presented in the following paragraphs does not reflect the documented management practices of SOEs.

The model distinguishes between the bottom three levels of management (Systems 1, 2 and 3) and the top two levels of management (Systems 4 and 5), which determine the future development and overall direction of the enterprise. At the bottom of the hierarchy, individual plants within each firm interact with the external environment (represented by the cloud-like graph on the left side of the figure) and generate lower-level System 1 production indices through these material input and output streams. Factors such as energy demand, raw material usage, and even employee attendance can all make up such an index. Each factory operates in a "basically autonomous" fashion, limited only to the operational constraints needed to ensure the stability of the entire enterprise. System 2 acts as a cybernetic spinal cord that transmits these production indices to the various factories and up to the operations supervisor (system 3) . By taking responsibility for the proper functioning of factories within the enterprise, these three lower levels prevent upper management from being overwhelmed by the nuances of day-to-day production activities. However, if a serious production anomaly occurs, jeopardizing the stability of the business, and cannot be resolved by the Director of Operations or System 3 after a period of time, the next level of management is alerted and asked to help.

Systems 4 and 5 only intervene in production in this case. Unlike the other management levels listed in the Bill hierarchy, System 4 requires the creation of a new management level dedicated to development and future planning that provides space for discussion and decision-making. This hierarchy does not exist in the vast majority of state-owned enterprises in Chile, nor, as Bill points out, in the management structures of most companies operating in the 1970s. In the diagram, it is shown as a development branch. System 4 also provides an important link between will control and automatic control, or in industrial management, central or decentralized management. Under normal circumstances, it allows lower-level people to act autonomously, but it can also trigger intervention from higher-level management if necessary. Ensuring a balance between individual liberty and central control proved crucial when trying to combine the Cybersyn Project with the political ideals championed by the People's Unity coalition, which this article will discuss below topics discussed in detail. The final layer of the model, System 5 , represents the "CEO" position held by a designated intervenor who determines the general direction of the business and the necessary level of production.

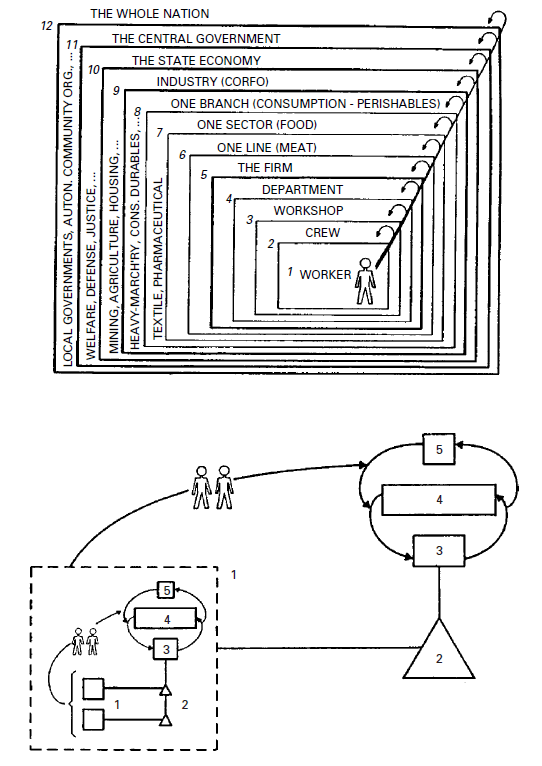

In Bill's view, this five-layer system not only provides the characteristic framework for all feasible systems; it also recursively exists in each of the five layers. "The whole is always encapsulated in each part - a lesson learned in biology, where we find in every cell the genetic blueprint of the whole organism," Bill wrote. Countries, companies, workers and Cells all exhibit the same set of structural relationships. Applying his organizational vision to Chile, Bill writes, "Recursively speaking, Chile is deeply embedded in the nations of the world, with governments embedded in nations—all considered viable systems." This The feature allowed the team to design a management system that could theoretically run anywhere from a factory to the presidential palace.

Armed with Bill's cybernetic model, and convinced it would be useful for Chile's economic transformation, the research team looked at their existing resources. By 1968, three American companies—NCR, Burroughs, and IBM—had fewer than 50 computers installed in Chile, the largest being the IBM 360 mainframe. According to the trade publication Datamation, Chile has fewer computers than Brazil, Argentina, Colombia and Venezuela. The previous Christian Democratic administration had encouraged U.S. investment and business with U.S. companies, but high import tariffs combined with an already high price tag made computer technology less attractive to Chilean industry than to its North American counterparts. The National Enterprise for Computers and Informatics (ECOM) is a central government agency established in the 1960s to oversee the purchase of computer technology in Chile and to provide data processing services on state-owned mainframes. In addition, it tried to maintain its computer monopoly by frequently rejecting requests from universities and private companies for more computing resources. The government has few mainframe computers and can only allocate time on one machine to the Cybersyn Project. The project leader initially used the best-performing IBM 360/50 , but later moved the project to the less heavily used Burroughs 3500 mainframe when processing delays on the 360/50 exceeded 48 hours.

The team also looked for a way to enable communication between factories, state-owned enterprises, sector committees, CORFO management and a central host at CORFO headquarters. Ultimately, they settled on the telex network previously used to track satellites. Unlike the heterogeneous networked computer systems used today, telex networks required the use of specific terminals and could only transmit ASCII characters. However, like the Internet today, the early telex network was driven by the idea of creating a high-speed information exchange network. The telex network later proved to be more valuable to the government than the processing power of the mainframe, reaffirming the shared belief of Flores and Bill that "information without action is waste".

After identifying the existing hardware options, the team frantically devised a workable scenario for the entire system and optimistically set a completion date of October 1972. The final design consists of four sub-projects: Cybernet, Cyberstride, Checo and Opsroom . Work on these projects would run from 1971 to 1973, during which time Bill would travel to Chile 11 times for about two weeks each. When Bill arrived in Chile for the second time in March 1972, shortages and rising inflation had turned the issue of economic control into a serious political issue. Although Flores' small team remained marginal in CORFO's overall structure, Flores was able to generate enough interest in his network of government connections to get the resources he needed to continue the project. It was at this time that the team first used the name Cybersyn to describe the scope of the entire system. It's a synthesis of "cybernetics" and "synergy," and the project name firmly articulates the team's belief that the whole system is more than the sum of its parts.

The first component of the system, Cybernet , expands the existing telex network to include every company in the state sector, creating a national communications network across Chile's 3,000-mile-long territory. Cybersyn team members occasionally take advantage of the promise of free telex installations to coax plant managers into supporting projects. An early report by Stafford Beer described the system as a tool for real-time economic control, but in reality each company can only transmit data once a day. This centralized design seems to run counter to the "People's Unity" coalition's commitment to individual liberties, but it coincides with Allende's statement: "We are and will support a central economy, and businesses must follow the government's plans."

Cyberstride is the second component of the Cybersyn system, which includes a suite of computer programs that collect, process and distribute data on each state-owned enterprise. Members of the Cyberstride team created a "quantitative flowchart of activities within each business, highlighting all significant activities," including the "social unease" parameter , which is calculated by comparing the number of employees absent from work on a given workday to those on the factory payroll. Calculate the proportion of people. Cyberstride statistically filters the "pure numbers" output by the factory model, discarding data that is within acceptable system parameters and directing important information to the next level of management. Just as importantly, the software uses statistical methods to detect production trends based on historical data, theoretically allowing CORFO to prevent problems before they start. If a particular variable falls outside the range specified by Cyberstride, the system issues a warning, called an "algedonic signal" in Bill's cybernetic vocabulary. Only the intervenor of the affected business will initially receive an algedonic warning and, within the given time frame, is free to deal with the issue as he sees fit. However, if a business fails to correct a violation within this time frame, members of the Cyberstride team notify the next level of management, the CORFO Sector Committee. According to Bill, this operating system gives Chilean companies almost complete autonomy in operating control, but still allows outside intervention in the event of more serious problems. He also believes that this balance between centralized and decentralized control can be optimized if each enterprise is given the correct recovery time before alerting higher management, ensuring maximum autonomy within the overall viable system .

Cyberstride represents the joint effort of a team led by Chilean engineer Isaquino Benadof and a team of consultants from Arthur Andersen in London. Isaquino Benadof is one of Chile's top computer experts and director of research and development at ECOM. A British team , led by Alan Dunsmuir, devised and wrote a set of interim procedures, which were handed over to the Chilean team for final revisions in March 1972.

Meanwhile, operations research scientists and engineers from CORFO and the National Institute of Technology (INTEC) in Chile toured factories across the country, met with workers and managers, selected about five key production variables , and created a flowchart of factory operations models, and translate those models into computer code that is read into the host using punched cards. They also determined the optimal recovery time to assign to each company, a process known as "designing freedom" before allowing algedonic signals to penetrate the system hierarchy. Project descriptions show that the team planned to network 30 enterprises by August 1972, and by May 1973 this number would increase to include 26.7% of all state-owned industries (more than 100 industries).

CHECO (CHilean ECOnomy), the third part of the Cybersyn program, is an ambitious program to model the Chilean economy and provide simulations of future economic behavior. Appropriately, it is sometimes called "Futuro". The simulator will serve as "government's experimental laboratory" -- an instrumental analogy that Allende often compares to Chile as a "social laboratory." Much of CHECO's work takes place in the UK under the direction of electrical engineer and operations research scientist Ron Anderton . The simulation program uses the DYNAMO compiler developed by MIT professor Jay Forrester , which is said to be one of Anderton's areas of expertise. However, the Chilean team, led by chemical engineer Mario Grandi, followed Anderton's model closely, painstakingly checking his calculations, asking detailed questions about the model and the computer tools used in its implementation, And sent a young Chilean engineer to London to study with Anderton. The CHECO team initially used national statistics to test the accuracy of the simulation program. When these results failed, Bill and his colleagues argued that there was a time difference in the generation of the statistical input, again underscoring the need for real-time data.

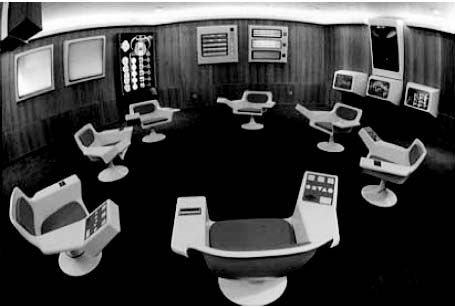

The last of the four components is the Opsroom , which creates a new environment for decision-making, modeled after the British WWII war room (Figure 2) . It consists of seven chairs arranged in an inward circle, flanked by a series of projection screens, each displaying data collected from state-owned enterprises. In Opsroom, all industries are unified by a unified system of icon representation, which is designed to help people with minimal scientific training extract maximum information. Bill recognized that the person sitting in the chair didn't have the skills of a typist, a profession often practiced by female secretaries. So the Opsroom team designed a series of large "big-hand" buttons as input mechanisms to replace traditional keyboards that people can "thump" to emphasize a point. Bill believes the design decision could allow technology to facilitate communication and bridge "the girl between themselves and the machinery" . Bill made his final remarks when he mentioned the traditional need for female typists. However, it also revealed gender assumptions in system design. Furthermore, Bill claimed that this "big hand" design made the room suitable for the ultimate use of the workers' council, rather than "a sanctuary for the government elite." The prototype for this room was built in San Diego in 1972, using projection equipment mostly imported from the UK. Although it was never used, it quickly captured everyone's imagination, including members of the military, and became the symbolic heart of the project .

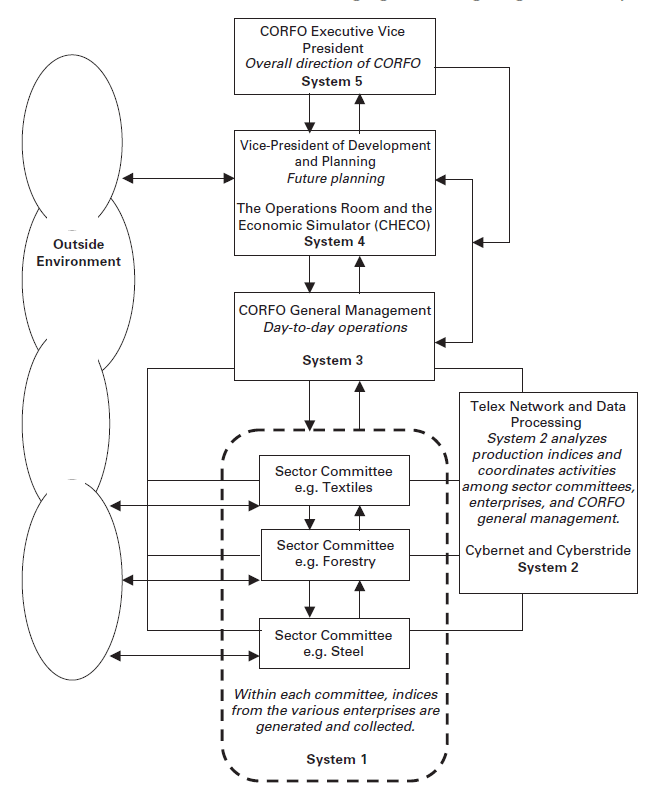

Figure 3 shows an idealized correlation of Cybersyn's intended architecture, CORFO's organization, and Bill's five-layer survivability system model - it should be noted that this diagram outlines Cybersyn's theoretical design, not its actual functionality and implementation Level. At this recursive level, sector committees collect and send production data on a daily basis using the telex network, which forwards the information to the data processing center (System 2) located at ECOM. A team of computer technicians crunched the data using a mainframe computer and a suite of Cyberstride-specific computer programs that searched for trends and irregularities in production performance. If the departmental committee (System 1) cannot resolve the production anomaly on its own, ECOM will issue an alert to the members of the CORFO General Management Committee (System 3). In the event of a particularly difficult or urgent issue, members of CORFO's general management will hold meetings with senior CORFO officials in the Operations Room (System 4) to discuss the issue and possibly reallocate resources or plan new ways of managing the social property sector . CHECO also operates at System 4 level and allows CORFO management to test their ideas before implementing them. If lower-level managers still cannot resolve the issue, then CORFO senior managers (System 5) use the data provided by the cybernetic toolbox to make informed decisions about how to intervene in production.

Original plans called for similar management hierarchies at the level of individual factories, state-owned enterprises and industry councils, although these ideas never materialized. Bill also started a series of training programs aimed at introducing the system to workers' councils and training them to use these new management tools to increase and coordinate their participation in factory operations. Perhaps, the grand scope of this "work in progress" explains the discrepancy between the operating model proposed in the previous paragraphs and the normal operating practices described by the Chilean engineers involved in the project. For example, Isaquino Benadof recalled that his office received messages from various businesses every afternoon, and after processing the numbers through a mainframe computer, transmitted the results to CORFO's telex control room , without notifying individual interveners and without going through the processing procedures outlined by Bill. This divergence between theory and practice will be further illustrated in the next section.

Despite these inconsistencies, work on each of the system components has progressed rapidly. The existing telex infrastructure greatly facilitated the early operation of the Cybernet network, the first and only Cybersyn component frequently used by the Allende government. On March 21, 1972, the Cyberstride kit produced its first printout, when Bill enthusiastically telexed Anderton: "The Cyberstride kit really works - none of this is possible, But we did.” Due to difficulties in finding suitable building space, and delays in receiving equipment from the British company Electrosonic, the Opsroom prototype was not completed until the end of December 1972, and at the time had very limited functionality. The economic simulator never passed the experimental stage. Because work on this project was interrupted, it is difficult to say how the complete system would advance the revolutionary process in Chile.

However, Cybersyn proved to be helpful to the "People's Unity" coalition, even if it wasn't done. During the October 1972 opposition-led strike, the communications infrastructure provided by Cybernet was extremely important to the government. In response to the strike that threatened the government's survival, Flores established an emergency operations center, where members of the Cybersyn team and other senior government officials monitored the 2,000 daily telexes sent from the north of the country to Activities in the South. The rapid flow of information on telegraph lines enabled the government to respond quickly to strike activity, mobilize limited resources and reduce the potential damage caused by strikes (Gremialistas). At the time of the strike, CORFO Energy Executive Minister Gustavo Silva praised the network for coordinating 200 trucks loyal to the government, offsetting the impact of 40,000 striking truck drivers. The government survived despite the decision to strike in October negatively impacted the "People's Unity" government, which included three senior military members in Allende's cabinet. The value of the telex network during the October strike helped Flores become a technologist and an important contributor to the surviving of the "People's Unity" government. Flores believes this prompted Allende to appoint him as economy minister. It also publicly demonstrates the utility of Cybersyn to governments, especially telex networks. A few weeks after the strike, Cybersyn participant Herman Schwember commented that "our actual influence and power has grown beyond our imagination".

Following the strikes, telex networks enabled a new form of economic mapping, allowing the government to compress data from across the country into a single report, written by CORFO each day, and sent to the Chilean Presidential Palace. These detailed charts provide the government with an overview of production, transport and crisis points across the country in an easy-to-understand format using data generated a few days ago. Using this form of reporting was a considerable improvement over the first six months required to collect statistics on the Chilean economy and enabled the People's Unity government to track the ups and downs of national production through September 1973.

Allende will continue to support the construction of Cybersyn during his presidency. On September 8, 1973—just three days before the military coup that ended his dreams and life—he sent a message to the Cybersyn team requesting that the command room be moved to the presidential palace in La Moneda.

"Revolutionary" Computing

Flores' success in the Gremio strike made him the newly appointed economy minister. Relatively unknown to the opposition, Flores believes he has an opportunity to increase his support by "building a different personal profile" based on "some sort of myth about (his) scientific credentials" on the basis of. However, amid extreme and growing economic dislocation, his new challenges as minister have convinced him that technology can only play a limited role in saving Chile from political and economic collapse. When Flores began walking away from the program and taking a new role in Allende's cabinet, Bill commented that their relationship "was fine when Flores was deputy minister" and now "has almost completely collapsed." ".

However, Flores' reaction does not mean that Cybersyn's designers ignored the complexities of Chile's larger political environment when creating this new technology system. Since its early days, the project has operated under the joint leadership of the Scientific Director (Bill) and the Political Director (Flores). However, Bill often went beyond his scientific mandate and recognized the utility of combining Marxist rhetoric with modernity to create a "powerful political tool" that could garner external support. He often uses phrases like "people's science" to emphasize the anti-technocratic nature of the Cybersyn project. In his public speech, Bill emphasized that Chile's best scientists were creating "a new management system" and avoided mentioning the contributions of his British colleagues. At Bill's request, renowned Chilean folk singer Angel Parra composed an original song called "Litany for a Computer and a Baby About to Be Born ", For factory floor use. The "baby" in the title refers to the rebirth of the Chilean people through socialist transformation. The chorus of the song also conveys the political intent of the project.

The song showcases the importance of technology in bringing about social change and its potential to eradicate political corruption. Its lyrics sound a battle cry, as well as a prophetic warning.

The political intent of this project goes beyond propaganda or rhetoric, it shapes the design of the entire system. Understanding the connection between Cybersyn's design and Allende's politics requires a deeper look at the president's plans to transform Chile into a socialist state.

cybernetic socialism

Allende's interpretation of Marx's writings emphasizes the importance of respecting Chile's existing democratic processes in achieving socialist reforms, a possibility that Marx alluded to but never materialized. Unlike previous socialist revolutions in Cuba and the Soviet Union, Chile's transition to socialism was democratic and included respect for election results, individual freedoms (such as freedom of thought, speech, press, assembly, and the rule of law), and public participation through elected representatives government decision. Allende had promised, "We would not be revolutionaries if we were limited to the preservation of political freedom. The 'People's Unity' coalition government would expand political freedoms." It must be noted, however, that Allende's personal or political freedoms The concept is at odds with individualism, which he associates with the selfishness of capitalism that undermines the collective well-being of the Chilean state. Unlike the central planning practiced by the Soviet Union, Allende's formulation of socialism emphasized a commitment to decentralized governance, involving workers in management, and reinforcing his professed belief in individual freedom. However, he also conceded that in the face of political pluralism, the government would support "the interests of those who make a living from their work" and that the revolution should start from above with a "firm guiding hand".

In Beer's model, the inherent tension between individual autonomy and the welfare of collective organizations mirrors the struggle between ideologies that exist in Allende's democratic socialism. Both emphasize the importance of individual liberty and the need for decentralization , while recognizing situations in which "the needs of one department must be sacrificed in order to explicitly meet the needs of others." Thus, the collective welfare of the state or the internal balance of the system takes precedence over mechanisms designed to ensure autonomy, autonomy, and freedom. Bill believes that this conflict of values can only be resolved at the top, and Allende is determined to support the belief that the Chilean government will support policies that protect workers' rights and interests, despite legislation that grants equal rights to the opposition.

However, the striking similarity between Allende's formulation of socialism and the cybernetic models that guided the construction of Cybersyn should not come as a complete surprise. Cybersyn was intentionally designed to be an instrumental incarnation of Chilean socialist politics. As Herman Schwember writes, “The viability of any conceivable programme of engagement is strongly dependent on the prevailing ideology.” Marxism not only guided the design of the system, but also provided Cybersyn’s continued operation. necessary dominance.

The Marxist tendencies in Cybersyn's design are clearly shown in two later systematic diagrams by Herman Schwember , both illustrating the centrality of worker involvement in Cybersyn operations (Figure 4) . The first diagram depicts the state, central government, industry (CORFO), and individual companies as nested viable systems, each recursively located within the other. The image of the worker appears at the heart of these systems, reinforcing the importance of the worker to the Chilean state . The second diagram shows a modified Bill's five-layer survivability system model with a figure of a worker inserted into both the System 1 and System 5 structures. Here, the worker contributes both physically and spiritually to the production process, a powerful response to Marx's critique of alienated labor in capitalist society, where the worker "is not free to develop his spiritual and The energy of the body, the exhaustion of the body, the degeneration of the spirit". The concept of alienated labor frequently appears in discussions in the Cybersyn group, and in Beer's view constitutes one of Marx's most influential ideas.

At a more specific level, the original design of the system created new channels for worker participation, such as inviting workers to provide their expertise to create a factory model. Plans to install low-tech operating rooms at every state-owned factory are also working to increase worker participation. These simplified rooms, with blackboards in place of projection screens, aid worker decision-making by facilitating communication and more intuitive factory operations, and will create a mechanism to enter the chain of command of senior management. An intervenor at appliance maker MADEMSA said that mapping important production indices provides a source of motivation for employees, who use the data as the basis for bonuses and as a means to boost collective production rather than individual output.

The link between Allende's Marxism and Bill's cybernetics is intentional, but it would be wrong to classify cybernetics as a Marxist science, just as it would be wrong to call Cybersyn an inherently Marxist technology Same. Beer believed that cybernetics provided a scientific method for revealing the laws of nature and remained neutral in its conclusions. Bill writes, "Science, properly applied, is indeed the best hope for a stable government. With cybernetics, we seek to eliminate prejudice by scientifically studying organizational problems." The advantage of cybernetics, therefore, is that it "provides A language rich and perceptive enough to make it possible to discuss the issue objectively and without any prejudice." As a neutral language, cybernetics "should not develop its own ideology; but it should demonstrate an ideology". This was an important point—Bill recognized that his cybernetic toolbox could create a computer system capable of increasing capitalist wealth or enforcing fascist control, an ethical dilemma that would later plague the project team. In Bill's view, cybernetics makes Marxism more effective through its ability to regulate social, political, and economic structures. Marxism, in turn, provides cybernetics with the purpose of regulating social behavior.

management revolution

Both Bill and Allende are trying to change Chile's economic governance system. Allende believes that Chile's transformation from a capitalist to a socialist state will require structural reforms and the systematic dismantling of previous production practices. Likewise, Bill's work aims to provide tools for transforming Chile's factory control system by reorganizing the industrial sector to follow his five-tier model, eliminating what he considers unnecessary bureaucracy, and giving factory workers new means of participating in factory management. In an earlier report in October 1972, Bill wrote that "the goal was to change the entire management of the industry and make Chilean industry fully effective within a year."

However, Bill's goals soon went beyond his original factory regulation goals and expanded to multiple aspects of the Chilean political system, including the installation of sensors ( algedonic meters ) in a representative sample of Chilean households, a project that would allow Chilean citizens Send their "happiness" and "unhappiness" to the government or TV studio in real time. Bill named the work "The People's Project" and "Project Cyberfolk" because he believed the meters would allow the government to respond quickly to public demands rather than suppress dissent. Just a month later, Bill wrote to Rau´l Espejo , director of the Cybersyn Project, "The reform of the entire government process has only just begun. Concepts are two orders of magnitude larger than network synergy." By December 1972, two months after the October strike, Bill had completely revised the scope of the project, drawing two levels of recursion instead of the one that originally described Cybersyn A single viable system. The original technical project has now been replaced by a new national regulatory project that begins with the people of Chile and ends with the Ministry of Economy; in this schematic, Cybersyn provides only an input, not a system as a whole.

While Beal's ambitious ideas still command the respect of his Chilean teammates - who often call him a genius - he has often faced resistance from those who say they are "politically unrealistic." That complaint resurfaced among his team members, some of whom preferred to build technological solutions rather than redefine government operations. Responding to a later report by Bill, Rau´l Espejo wrote, "In the short term, I think ideological issues within government come second, and we can make a difference for an efficient economy. Problems build models. Through them, we can eliminate bureaucracy." Throughout 1973, Bill grew increasingly disillusioned with Espeio's technocratic tendencies; It's not an ideological issue.

From 1971 to 1973, Bill expanded project objectives from economic regulation to political structural transformation. However, the success of the project depends on members of the industrial sector and the Chilean government accepting the entire system. Adopting a single component, as Bill himself admits, can be disastrous and lead to "the old system of government plus some new tools -- because if inventions are repealed, the tools used are no longer the tools we made ourselves. , they can become tools of oppression.” Having said that, observers from within Chile, around the world, and even within the project team tend to see Cybersyn as a set of technical components rather than a synergistic whole—indeed Separate the technology from the ideology behind its creation. According to Bill, members of the Chilean opposition wrote to congratulate Cybersyn on the design — which, of course, did not emphasize worker involvement. The centrist Chilean news magazine Ercilla separated the project from socialist goals in a different way, publishing an article in January 1973 - an allusion to George Orwell's 1984 picture of a totalitarian world . The same sinister comment appeared in the headline of the right-wing magazine Que´ Pasa.

Internationally, similar views have sparked criticism from British publications New Scientist and Science for People, both of which accused the system of being too centralized and abusing Chileans. Similar criticism came from the US, especially from Herb Grosch , a mainframe computer expert at the National Bureau of Standards, who refused to believe that "Bill and his team could in a few months, assembles a new model in the same hardware and software environment.” In a scathing letter to the editor of New Scientist, Grosch wrote, "I think the whole concept sucks. It's a good thing for humanity, and for Chile it's just a nightmare." Throughout 1973, Bill received invitations from the repressive governments of Brazil and South Africa to create similar systems. Given the political background of these countries in the early 1970s, it's easy to sympathize with Bill's lament, "You can see how wrong I am."

According to Bill, the success of the system depends on its acceptance as a system, a network of people and machines, a revolution in behavior and tool capabilities. In reality, however, the opposite is true. Not only were these tools not designed in an unacceptable way, but members of the Cybersyn team themselves failed to fully understand the cybernetic principles behind their development, nor could they communicate the rationale behind the system to members of the industrial sector. In the eyes of many Chilean engineers involved in the project, mastering the theory of cybernetics has been replaced by a search for order against economic chaos or the development of new technologies. Contrary to Bill's view of the project, many engineers see their work as primarily technical rather than political, and see the ultimate goal as creating a new tool for economic management. A member of the Chilean team responsible for creating a factory model for the textile sector summed up the situation poignantly:

The ultimate goal of "management revolution" was not accepted or even understood. I've yet to see a manager really motivated by the core concepts, and worse yet, only a tiny minority of the team developing the work have come up with the relevant concepts. Ultimately, your work will be accepted as long as it provides the tools to enable more effective traditional management. It's not even a half-assed revolution, but a hybrid one that, if not taken seriously, could eventually lead to a new bureaucracy.

In other words, these new technologies did not revolutionize, but further consolidated many management practices that disenfranchised workers prior to Allende's presidency.

In factories, technocrats often mask ideology. While Cybersyn engineers have been given clear instructions to work with workers' councils to develop quantifiable models detailing the plant's production capacity, often the opposite is true, with engineers treating workers in a condescending rather than cooperative manner , or he would ignore the workers entirely and deal directly with management. Furthermore, they often obscure or ignore the political aspects of the project in favor of its technical merits, thereby avoiding potential labor conflicts. While the project team did develop training programs to educate workers on how to use these new management tools to increase engagement levels, those efforts were interrupted before they came to fruition. As a result, most employees are still unaware of the Cybersyn system and the management tools it provides.

On paper, Bill and CORFO are committed to promoting social transformation and increasing worker participation at all levels of government, and the interactions between these Cybersyn engineers and state sector workers reflect Chilean social and cultural hierarchies and reinforce the project image of the technocratic. Later, a member of the project team summarized the new roles created for scientific experts in a paper. According to the authors, "individuals [workers] should have effective organic feedback channels to all parts of the system", but at the same time learn to accept expert advice and even ask for it when necessary. This will help them "avoid confusing their roles". The Opsroom design further confirms that Cybersyn will maintain existing power relationships around production rather than transforming them. By removing the keyboard, "eliminating girls" between users and machines, while designing the system to reflect and encourage masculine communication styles, the Cybersyn team demonstrated a complicit understanding that state power would remain primarily in Chile in male hands. This design choice also suggests that "workers" will continue to refer exclusively to those employed in factories, excluding those who do clerical work.

As Bill describes, Cybersyn's success hinges on creating a new economic management structure that fundamentally changes the relationship between workers, managers, engineers and public sector employees. However, reaching a steady state or steady state depends on controlling the number of variables at the core of Chile's economic transition. This premise creates two immediate problems . First, for Bill's model to become a functional reality, existing political, economic, and social structures must be altered, a near-impossible task in Chile's fragmented political context. Revolution through democracy rather than violence limits potential avenues for change, and after many setbacks, Bill wonders, "Does it take more courage to be a cybernetic expert than to be a gunman?" Second, Although the factory model designed by the project team members has some structural flexibility at the industry level, Cybersyn as a whole does not have the capabilities required to effect the transition of the Chilean economy from capitalism to socialism, nor does it possess the control that marks Chile's unprecedented The capacity for unexpected events of the revolutionary road. Instead of a regulatory transformation, Cybersyn fell victim to the instability created by Allende's plans for socialist reform. Project engineers found they were trying the impossible: simulating a changing economic system using only the subset of variables needed to understand the system. Production, as measured by the flow of raw materials and manufactured goods, is only one facet of the Chilean economy—compared to economic dislocations such as inflation, consumer shortages, political infighting, U.S. foreign policy, black market hoarding, labor strikes and rising social unrest. The Chilean economy is increasingly dwarfed. Labour in particular, not just as another factor of production, but as a subject of self-conscious individuals capable of criticizing and resisting the functioning of the state. In hindsight, Beer writes, “the model we used did not adequately represent the changes that occurred during Allende’s tenure, as these were changes in economic management, not ownership in the legal sense.” Cybersyn was not as Beer envisioned. That way, to transform Chile's economy through massive social restructuring, Cybersyn, instead, simply struggled to regulate day-to-day operations, a task that became increasingly difficult in 1973.

However, this does not mean that the system is a complete failure, just as the system's ideological consistency with Allende's reform plan does not mean that it is a success. As with the transition, regulation has played an important role in keeping the Allende government afloat. As Chile's socio-economic situation descended into disarray, the need for social and political regulation gradually took over the previous priority of structural transformation. While Bill insists that the system can only function properly as a whole, the components in the prototype have greatly improved the government's ability to respond to and manage strike activity, as well as map complex economic fluctuations using recently generated data. By May 1973, 26.7% of state-owned industries, which accounted for 50% of the sector's revenue, had been incorporated into the system to some extent.

Following the October 1972 strike, CORFO established an Information Authority responsible for expanding the scope of industries associated with the system and increasing the use of Cybersyn data in state operations, an initiative by CORFO Chairman and former Minister of Economy Technical work supported by Pedro Vuskovic . These regulatory contributions of the system help the Allende government's day-to-day economic operations - if poorly regulated, the October strikes or any other economic crisis in Chile has the potential to shorten the lifespan of the People's Solidarity and limit them further political choice. In his final report on the project, Bill summed up his views on the importance of regulation for Chile's path to democratic socialism:

I imagine our invention as a revolutionary tool. I mean, "The Way of Production" is still a necessary feature of the Chilean Revolution, but this "The Way of Regulation" is an additional requirement of a complex world that Marx or Lenin did not experience.

In the light of Bill's experience applying cybernetic principles to the political situation in Chile, his new interpretation of the revolution is understandable. It seems more plausible, however, that this new emphasis on regulation does not stem from changes in the complexity of the world, nor from an oversight in Marx's philosophy. Rather, it reflects how science and technology are influencing and redefining our conception of the political order and the tools available to orchestrate social change. The history of the Cybersyn system further illustrates that political ideologies are not just worldviews, but also contribute to the design and application of new technologies that politicians, engineers, and scientists then use to create and maintain new patterns of state power.

Cybersyn shows how the study of technology can advance our understanding of historical events and processes in Latin America. Considering that building a technological system requires a different mix of actors, in this case politicians, foreign experts, engineers, and factory workers, an academic analysis of such a system can illustrate how members of each group articulate what they face. challenges and their place in the world they create. Disagreements about implementation (such as worker involvement), conflicting interpretations of its potential for control, and the politics of day-to-day design decisions (such as whether to use keyboards in the operating room) do not simply reflect views of technical feasibility and plausibility. Instead, they reveal class resistance to economic and social change, the scope of Cold War ideology, and the limits of the redistribution of power in Chile's socialist revolution. In addition, the system reveals the unstudied values of science and technology during this period in Chilean history and specifies the plans for the ideology of "people's solidarity" pursued for economic transformation.

Furthermore, the history presented here attests to the uniqueness of the Chilean socialist experiment. This project is unique in that it applies cybernetic science to economic regulation and state governance , but its emphasis on decentralized control, a technique that reflects the distinctive features of a "people united" government. While we may question the exact extent to which this system has contributed to stemming Chile's growing political, social, and economic unrest, its history does provide a new perspective on the Chilean experience. In contrast to the chaotic picture of shortages, strikes and protests that have characterized the era, Cybersyn presents a different history. Here we see members of CORFO, INTEC, ECOM and their British interlocutors striving to achieve different dreams of socialist modernization, technical competence and normative order. This will be a dream that some Cybersyn team members continue to pursue until the day when the military imposes a very different order on the Chilean people, project team members flee CORFO headquarters and hide project documents under their armpits to save for the future.

On the morning of September 11, 1973, the Chilean military launched a coup against the Allende government. It began in the city of Valparaiso and continued to grow in strength as the army marched south toward Santiago. At 2 p.m., Allende was dead, his dreams engulfed in ashes in the flames of the presidential palace. After the coup, the military made several attempts to understand the theoretical and technical aspects of the Cybersyn project. When these efforts failed, they decided to dismantle the operating room.

Nearly all of the Cybersyn participants in the study claimed that the program changed their lives. Most now hold senior positions in universities or technology-related industries and continue to use the knowledge gained from the project to this day. However, despite Cybersyn's contributions to the technological and political history of Chile during this widely studied period, it has all but disappeared from the wider Chilean memory until recently. Like many other victims of Pinochet's dictatorship, Cybersyn disappeared.

Compiled from: Designing Freedom, Regulating a Nation: Socialist Cybernetics in Allende's Chile

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!