Introduction to the Zettelkasten method

Compiled from: Introduction to the Zettelkasten Method

Why are you reading this introduction? The Zettelkasten method is more than just a tool to get some work or project done. This is a holistic method of how to deal with knowledge in life.

The Zettelkasten method is an amplifier of your efforts in the field of knowledge work. It's so effective that many people say they're having fun using it, and some even compare it to addictive games like World of Warcraft. But that's just the result of sustained effort.

The Zettelkasten method takes some practice. First, you'll feel like what you're doing is useless. But with a little practice and patience, it will bring surprises and yield gems of knowledge.

This introduction is designed to guide you on your first steps towards excellence. Go down this path and your Zettelkasten will provide you with the tools for intellectual growth.

If I were to explain it to someone unfamiliar with the concept of Zettelkasten, I would describe it this way:

Zettelkasten is a personal tool for thinking and writing. It has hypertext features that make the web of thoughts possible. Unlike other systems, you create a web of ideas rather than notes of arbitrary size and form, and emphasize connections rather than collections.

The Zettelkasten as we know it today was really developed by Niklas Luhmann, the godfather of the Zettelkasten method, the most powerful thinking and note-taking tool available.

Luhmann's Zettelkasten

Niklas Luhmann was a prolific social scientist. He has published 50 books and more than 600 articles. He didn't do it on his own. He has a pretty good company.

There are also more than 150 unfinished manuscripts in his estate. At least one of them is over 1000 pages long. His productivity even exceeds his published work.

Niklas Luhmann himself says that his productivity stems from using Zettelkasten. This resonated with people studying Zettelkasten's method. Niklas Luhmann 's Zettelkasten is a collection of notes on paper slips with a special twist: it's a hypertext that he can use in a reasonable time and energy to browse the chest of drawers that contains all the notes. "Reasonable" means reasonable for Luhmann, obsessed with his social theory and a workaholic. Hypertext needs to be surfable. On Wikipedia, you just need to click a link to go to the next article in the Wikipedia hypertext. If the hypertext was paper based, it would require more work to follow the link. Another problem is that you need a starting point. So Luhmann created his Zettelkasten to make his collection of notes surfable. He needed an entry point and a mechanism for navigating from note to note in an efficient manner.

We are lucky because we have access to powerful digital tools. Handling a physical Zettelkasten is more difficult and labor-intensive than a digital Zettelkasten. We don't have to be workaholics to benefit from the Zettelkasten method.

Why are we so interested in Luhmann's Zettelkasten?

First, we fantasize about what it means to be as efficient as Luhmann. Luhmann's Zettelkasten seems to have inspired people, which is one of the main reasons for the interest in his production methods.

Second, Luhmann's Zettelkasten is a great improvement on note-taking and knowledge work methods. It amplifies your efficiency. Produce more in less time. If we accept this, we can improve our note-taking in several ways:

- We can improve the connectivity of our thoughts. The hypertextual nature of Zettelkasten allows us to relate ideas. These connections enable new insights. Insights do not arise in a vacuum. They are the result of making new (unexpected) connections.

- We can be more productive. The Zettelkasten method simplifies our workflow by providing clear guidance. This in turn reduces friction. It is common to enter a process stage, which further increases productivity. I even allocate two days a week to make the Zettelkasten work my top priority and let the Zettelkasten process happen.

- We no longer waste effort. Even if your notes aren't used on a project you're currently working on, you've prepared knowledge for future projects. At the very least, you increased the depth of processing information on the subject.

- We can solve more complex problems. The Zettelkasten method allows you to focus on a small part of the problem, then take a step back and look at the problem with the big picture.

- Ordinary note-taking methods can lead to bloated messes over time. Zettelkasten, on the other hand, automatically adjusts to the size of the problem you're trying to solve. This is what Luhmann talks about when he writes about "internal growth" in his handbook.

- The Zettelkasten method will make your writing easier, more coherent, smoother, and more persuasive. A major problem in writing and thinking is our limited ability to follow a line of thought for long periods of time. Just think about meditation. Even something as simple as breathing can be difficult to focus on for a few minutes. Imagine how difficult it is to spend weeks or even months thinking about a problem in order to write a paper. Zettelkasten will keep your mind alive and help you persevere.

We have to take notes to solve problems effectively. In the words of Luhmann ( Learning How to Read, Niklas Luhmann ):

What should we do with what we wrote down? Of course, in the beginning, we mainly produced garbage. But we are taught to expect something useful from our activities, and without any useful results, we quickly lose confidence. Therefore, we should reflect on how we arrange our notes for future reference.

The result of Luhmann's own notes was his Zettelkasten. Let's dig a little deeper and see how he does it to extract some general principles.

Fixed address for each note (Note)

If you want to cite a single note, it needs to have a fixed and unique address by which you can identify the note. This makes finding possible. In our digital age, this question is rarely thought of unless you are a software developer. We are used to searching on the web, and within a very short period of time, our searches will bring us results. However, when you're dealing with a pile of paper notes, you need to make it possible and bearable. Luhmann's method is an ingenious numbering system .

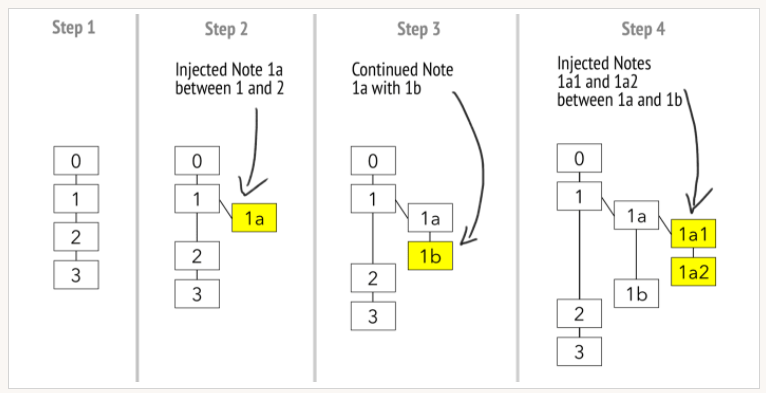

The first note is assigned number 1 . If you add a second note unrelated to the first, it will be assigned number 2 . But if you want to continue the first note, or inject something into its content, comment on it, or something like that, you can branch off . The new note will be designated number 1a . If you continue with this new note, you will continue to use 1b . If you then want to comment on note 1a, you can create a note with address 1a1 . So, in a nutshell, every time you continue a train of thought, you increment the last position in the address, whether it's a number or a character in the alphabet. And when you want to expand, intersperse, or comment on a note, you can take its address and add a new character. To do this, you need to use numbers and characters interchangeably. Luhmann's numbering system had two effects on recreating his method:

- It enables organic growth . Luhmann didn't use the term hypertext, but if he were living today, he might. This organic growth is exactly how wikis and their wiki linking feature work. You have a text, but want to expand by a point. You can branch from the current page, which basically injects another text into the current page, but hides its content at the same time.

- This makes linking possible. The emphasis on links more clearly suggests the hypertextual nature of his Zettelkasten. The non-linear link structure is the main feature of hypertext. In his manual on how to create a Zettelkasten, he writes: As long as you can link to a new note, it doesn't matter where you put it.

His numbering system made paper-based hypertext possible. For Luhmann, the workload is affordable.

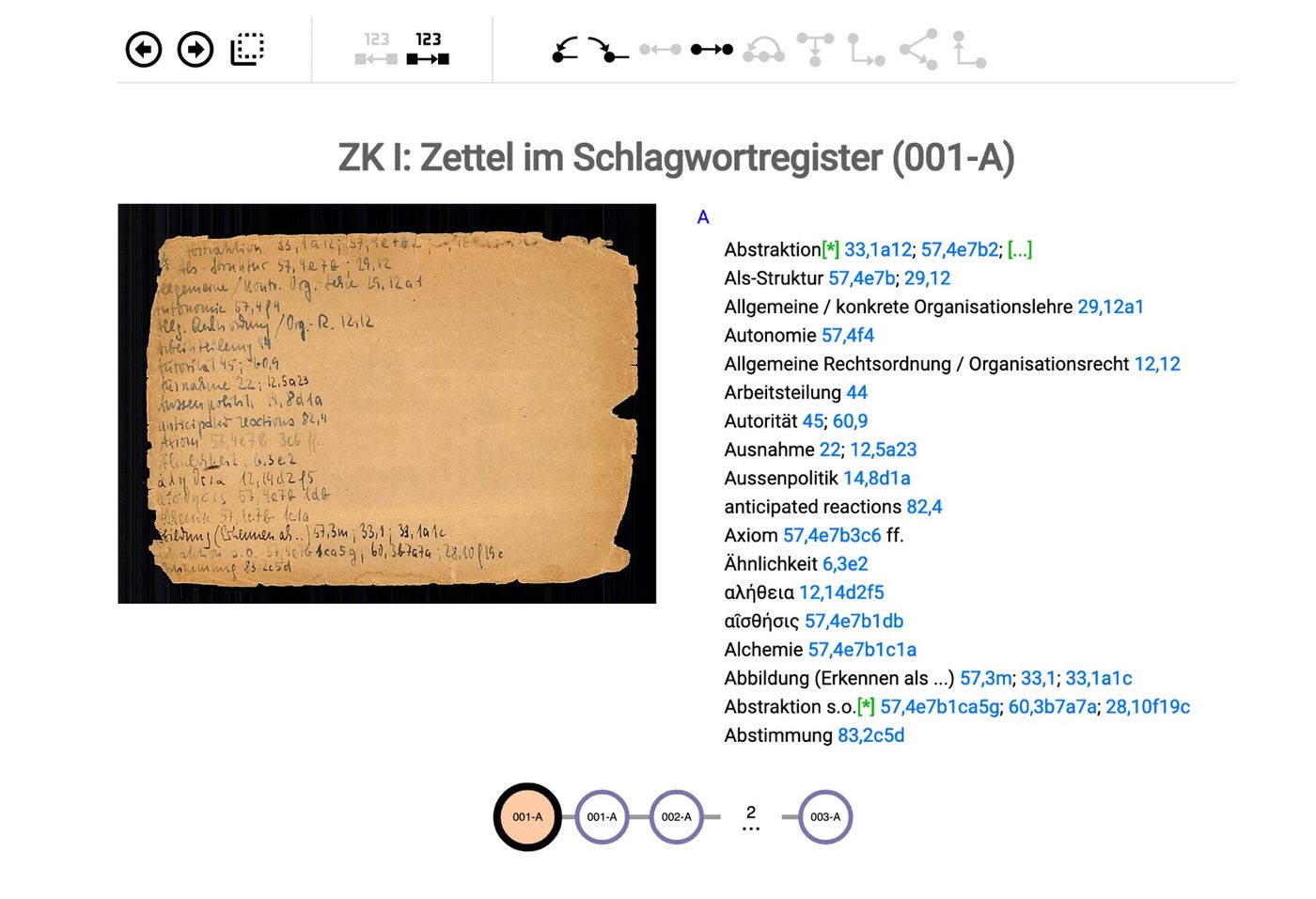

At this stage, we have a browsable hypertext. But we don't have anything like a search engine to get into hypertext. "Where to start?" is the question Luhmann needs to answer. He uses his register as a starting point, his entry point.

Luhmann's register can be mistaken for a tag system . However, individual notes were not tagged, nor did he establish a tagging system to organize his Zettelkasten.

In his register, each entry has very few IDs, sometimes just one, with one next to each entry. His register is purely a list of entry points, not a tag list. For example, the term system has only one entry. The term played a huge role throughout the field when Luhmann was developing a systems theory. The register is just a list of possible entries for the largest and most important set of notes. After finding the hypertext entry, he relied on the linking system to start browsing.

The fixed address of each note is the alpha and omega of the Zettelkasten world. Everything is possible because of it.

If you want to replicate the functionality of Luhmann's Zettelkasten, you have to create a hypertext and restrict your access through a page at the heart of a topic, from where you can continue to enter by link.

Zettelkasten is a tool for personal thinking and writing

Compared to other methods, Luhmann decided not to make his Zettelkasten stiff, opting instead for an organic approach. There's a reason why his own manual is titled " Communicating with Slip Boxes " rather than "A slip box as a writing and thinking tool." Our reference point is that the Zettelkasten method is an organic, nonlinear, and even living note-taking method.

Let's start with the most important features of Zettelkasten:

- It is hypertext.

- It follows the Principle of Atomicity.

- It's personal.

First, it is some kind of hypertext, not a single text, not just a collection of texts, but texts that refer to each other, interpret each other, extend each other, and use each other's information. The difference between a regular note-taking system and Zettelkasten is the emphasis on forming relationships . Zettelkasten prioritizes connection over collection. The difference between text and hypertext is that the former is linear and the latter is organic.

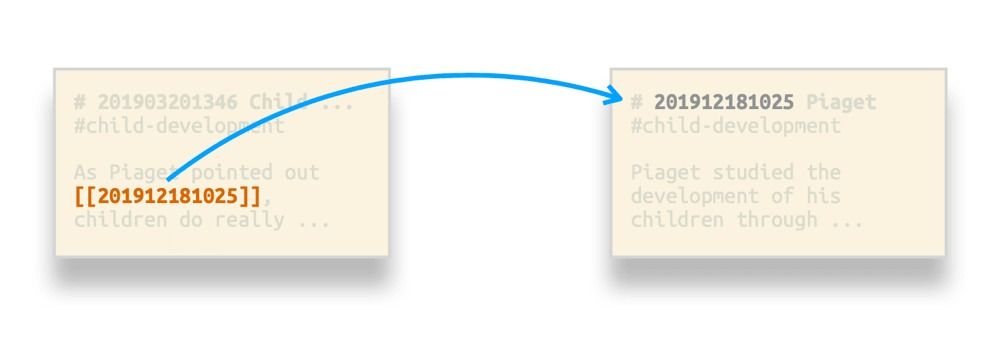

To be a hypertext, Zettelkasten takes multiple texts or notes, which you can connect via hyperlinks. We call a separate note Zettel. Zettel means "paper slip" in German. They are the smallest building blocks of Zettelkasten.

Every Zettel needs a unique address by which we can reference it to establish connections between Zettels. Then there can be hypertext, and the note-taking system can be called Zettelkasten.

Second, a Zettelkasten needs to adhere to the Principle of Atomicity . That is, each Zettel contains only one unit of knowledge, and only one. These units are the atoms to which the principle of atomicity refers. To figure out what atoms are, it helps when we ask ourselves what molecules we want to create with our note atoms. What is the (knowledge) unit with its own address? The answer is: a thought. Let's explore some examples that don't have thoughts as atoms.

For example, books have addresses and cross-references. They have chapters, sections, and pages. All books have unique numbers and can be cited. However, you cannot cite a thought, an idea, or anything. Chapters, sections, and pages are more like coordinates. A thought may be spread throughout the book! You can't just refer to a point and just refer to it directly. Books are not a web of thought.

Wikipedia is also not a web of ideas, because you can only link to articles and chapters within it, but not to individual ideas within the text. None of the addresses matched any thought. Wikipedia is not going to do such a thing. In contrast, Wikipedia is an encyclopedia, and each article contains information on a topic. Wikipedia is not a thinking tool, but an information retrieval tool.

By contrast, citing atomic notes is unequivocal: when you cite it, you know what a "thought" is. There shouldn't be any room for guesswork. That's what the atomicity rule is about: ensuring that the boundaries between content layers and notes are consistent and unambiguous. Then, and only then, can it be a reference to an address, like a reference to a thought.

The Zettelkasten is an instrument of thought, so it needs to have a single thought as its basic unit. To connect ideas, give each idea a referenced address. In the words of our "Zettlers": There must be a Zettel for every thought.

Third, there is one Zettelkasten for everyone, one for each Zettelkasten. Thinking and communicating with others are different processes. You want to make your Zettelkasten a tool for personal thinking.

That doesn't mean that creating a shared, project-specific hypertext isn't useful. But that's not what we call Zettelkasten.

Let's go back to our short definition:

Zettelkasten is a personal tool for thinking and writing. It has hypertext features that make the web of ideas possible. Unlike other systems, you create a web of ideas rather than notes of arbitrary size and form, and emphasize connections rather than collections.

With this, we have a working definition. How did you Zettelkastenize your thinking and writing?

The Anatomy of a Zettel

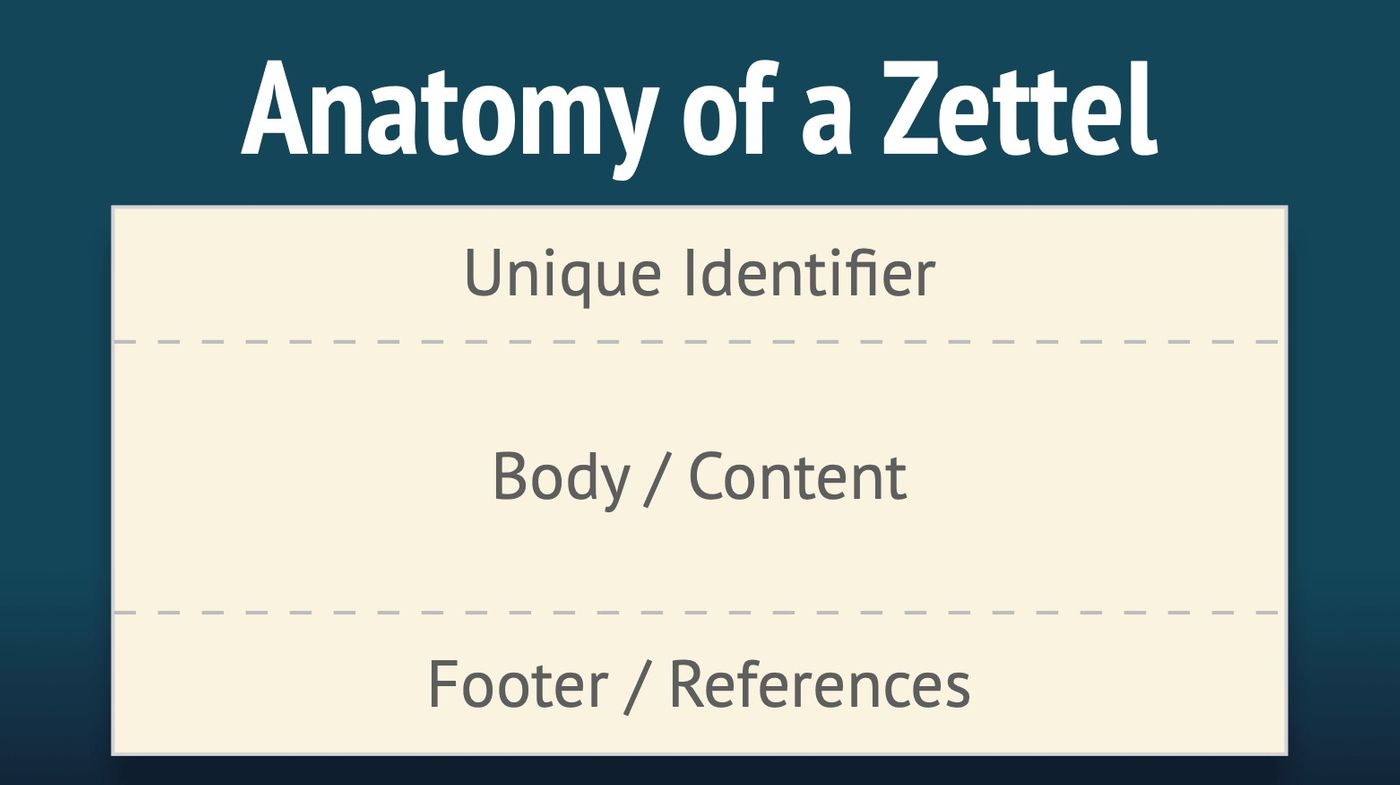

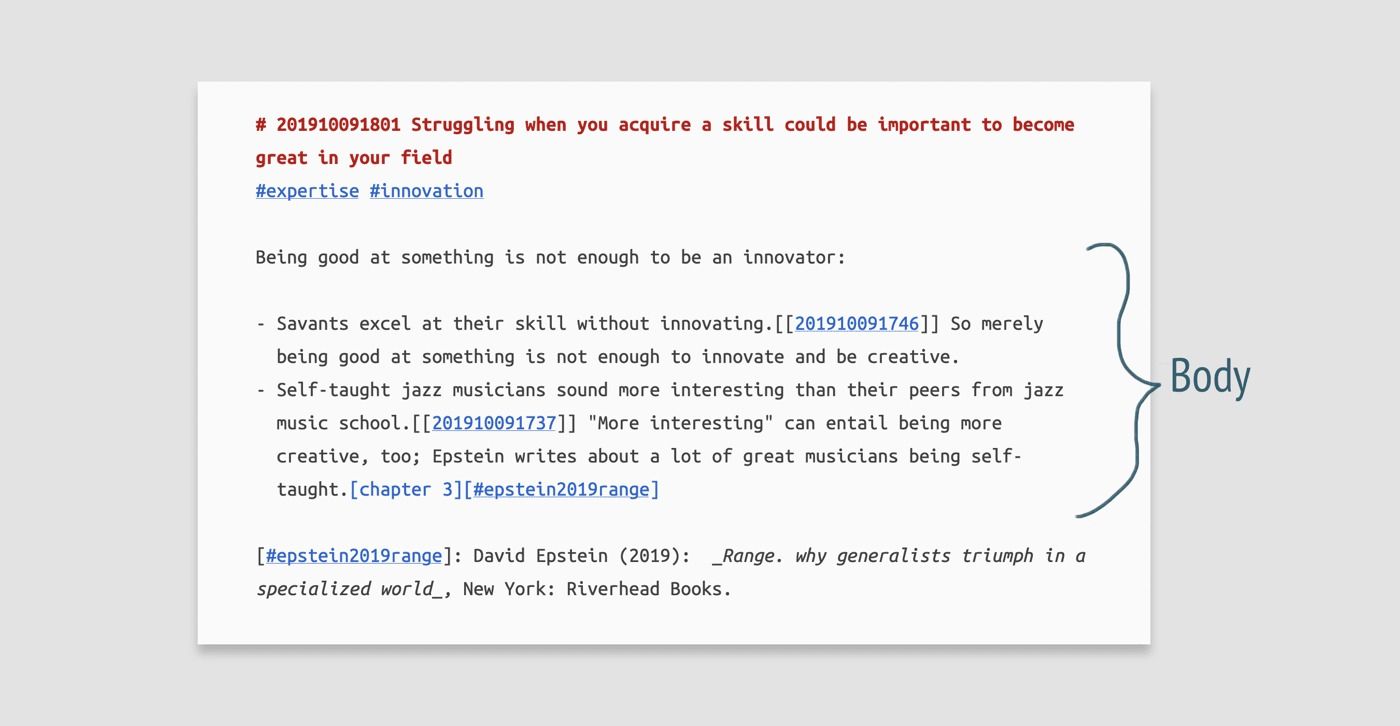

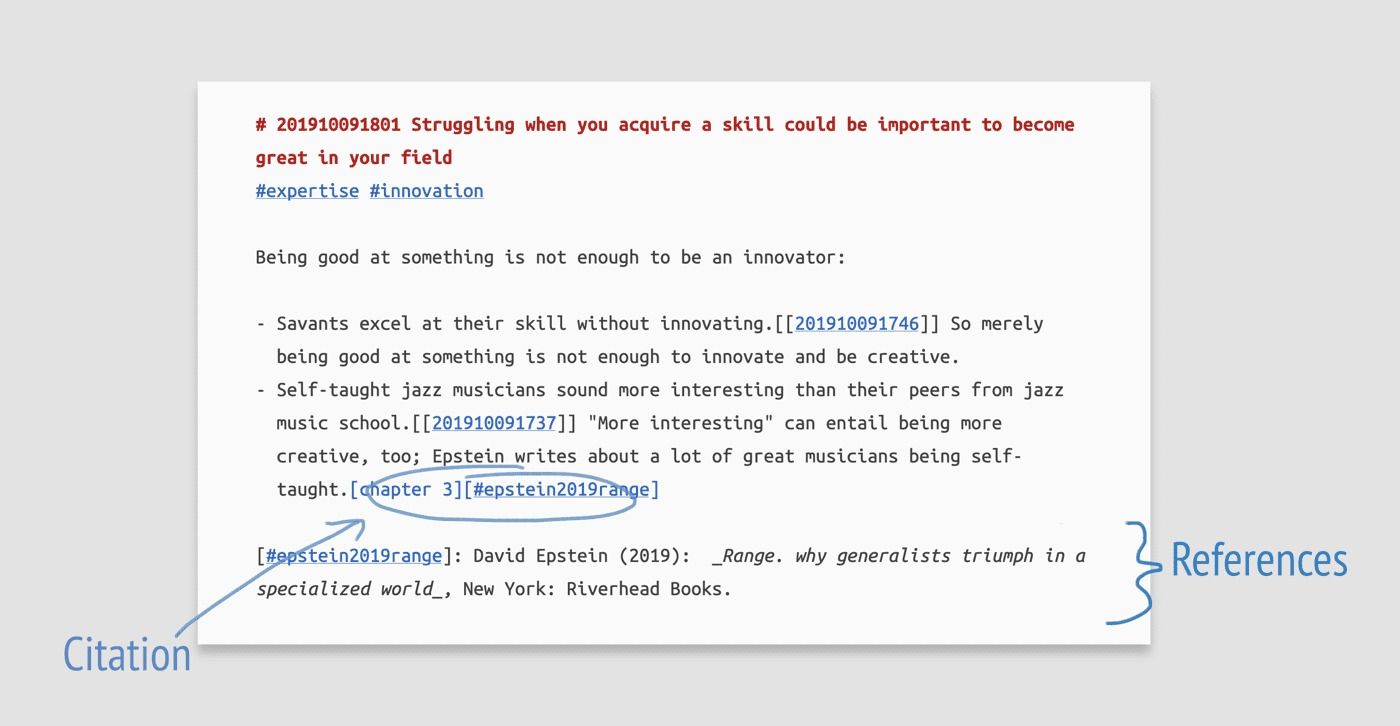

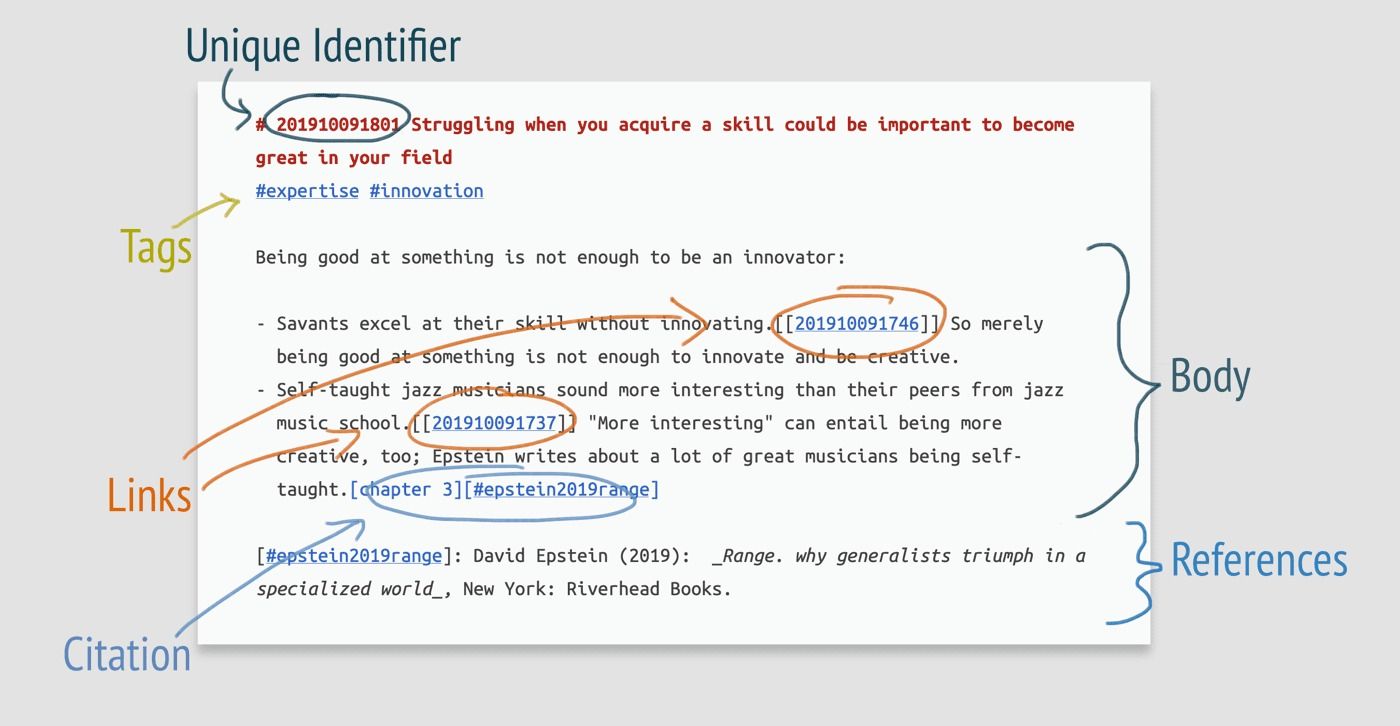

What does a single note, a Zettel, look like? Each Zettel has three components:

- unique identifier. This gives your Zettel a clear address.

- The body of Zettel. This is where you write down what you want to acquire: pieces of knowledge.

- References. At the bottom of each Zettel, you either cite the source of the knowledge you acquired, or leave it blank if you acquired your own ideas.

It's actually that simple. If you're wondering if you're doing it right, go back to these simple basics. To enable hypertext, you need at least an address, which is a unique identifier, and of course some content in your notes.

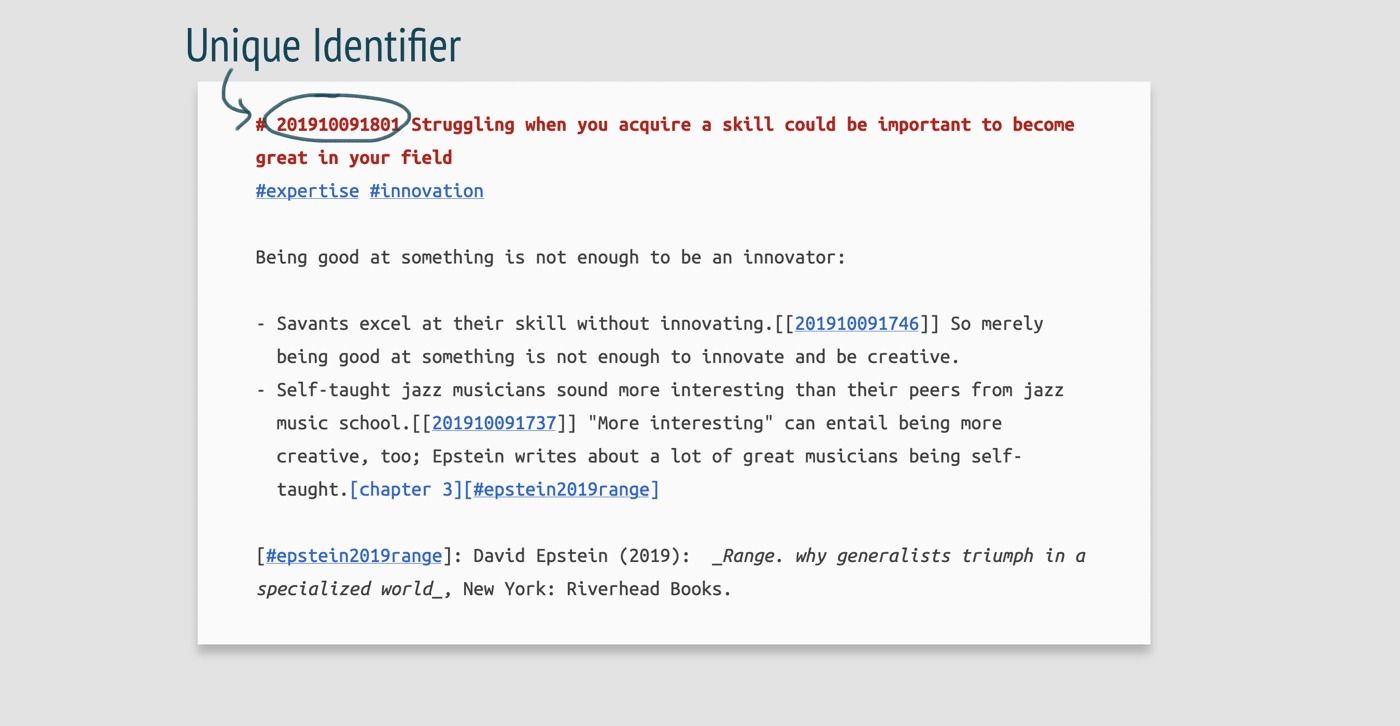

unique identifier

A unique identifier (ID) is a prerequisite for creating a Zettelkasten. Only with a unique identifier can you access Zettel individually. Only with this condition can you create a web of ideas that will help you in your knowledge work.

There are several ways to identify notes, the most common are:

- Of course there is Luhmann-ID . You create some kind of arbitrary hierarchy where each Zettel has a possible position. With paper Zettelkasten, I recommend this technique as it helps with its organization. Other types of IDs won't work as well on paper.

- You can choose a Time-based ID . Unlike the paper Zettelkasten, the digital Zettelkasten has no real place to put your notes. To create hypertext, you need an address, not a place. Timestamps are a very simple way to create a unique string of numbers for you to refer to. A sample time-based ID should be: 202006110955. 2020, June 11, 9:55am.

- You can use any arbitrary unique string . You can just use an incrementing number, execute a program, generate a random but unique string, or whatever else you want. The ID can be kept short. But some simplicity is sacrificed, and there is no way to generate an ID manually. At the same time, this sacrifices readability when Zettel was created. Therefore, we do not recommend this method.

- You can also use Zettel's title as its ID. It can be used as an ID as long as it is unique. So if you want to keep the link intact, you can't change the title unless you change any references to it. There is some software that can do this for you, but we don't recommend it. We prefer a software-independent approach, maintaining our independence from the software.

Zettel's body

The text of Zettel contains the knowledge you want to acquire. It can be an argument, a concept, or anything like that.

The most important aspect of Zettel's text is that you write it in your own words . There is nothing wrong with quoting verbatim. But one of the core rules of making Zettelkasten work for you is to use your own language, not just copy and paste what you find useful or insightful. This forces you to create at least a different version, your own. This is one of the steps in increasing your understanding of the material, it improves your recall of the information you are processing. If the content of your Zettelkasten is your own and not just a bunch of other people's ideas, then it will truly be yours.

The length of a Zettel is directly related to the type of hypertext you want to create. Do you want to create a web of excerpts? Then a Zettel should contain only one excerpt. Do you want to create a web of ideas? Then a Zettel should contain a thought. Zettel is the base entity with its own address. So the length of the Zettel, which is the length of the atoms you want to create the molecule, is determined by what you want to achieve. Your thinking operates in units of thought. A Zettelkasten captures your thoughts and their relationships because you designed them that way. Therefore, we recommend limiting each Zettel to one thought. Then your Zettelkasten will help you think, not just assist you in creating excerpts.

On the Zettelkasten forum , @Nick asked how picky I was and what was the nature of the information I entered. Well, it depends on what you're thinking. I suggest you stick to knowledge rather than information.

The difference between knowledge and information is actually quite simple. Most of the time information can be summed up in one sentence. Many times, it is "dead". Information is just that.

An example of a message could be:

At this time (2020-05-20 09:14), I, Sascha, wrote the first draft of an article titled "Zettelkasten -- Introduction".

What do you use this for? As a historian of the Zettelkasten method, you can process it to get a timeline of introductory essays on the Zettelkasten method, thus tracking how the topic unfolded on the Internet. You will then create an empirically based message for your historical research. But just for presentation, it's pretty useless. For most of us, it's just dead information, not knowledge.

In general, you should always gain something from the information you process. You should turn information into knowledge by adding context and relevance. Even if you don't use the knowledge you create directly, as long as you enrich the information with relevance, you're on the right track. You don't have to worry about what Zettelkasten forum user @grayen wants to know when taking notes from articles on the internet:

I sometimes have a hard time deciding if it's worth writing a detailed Zettel, what kind of article is worth writing a Zettel, but I don't want to write it for the sake of writing, and most of the time I'm not sure if it's just something short-lived, or if it's real Worth keeping for the long term, not just to deal with a specific thought/question. I don't want to turn my Zettelkasten into a hustle, aka a procrastination.

When in doubt, write notes on your deadline. If you know if every piece of knowledge is relevant to your final product, there is no reason to take notes because you already have the final product in mind. Every bit of knowledge you add has potential usefulness that you may not see when you generate it.

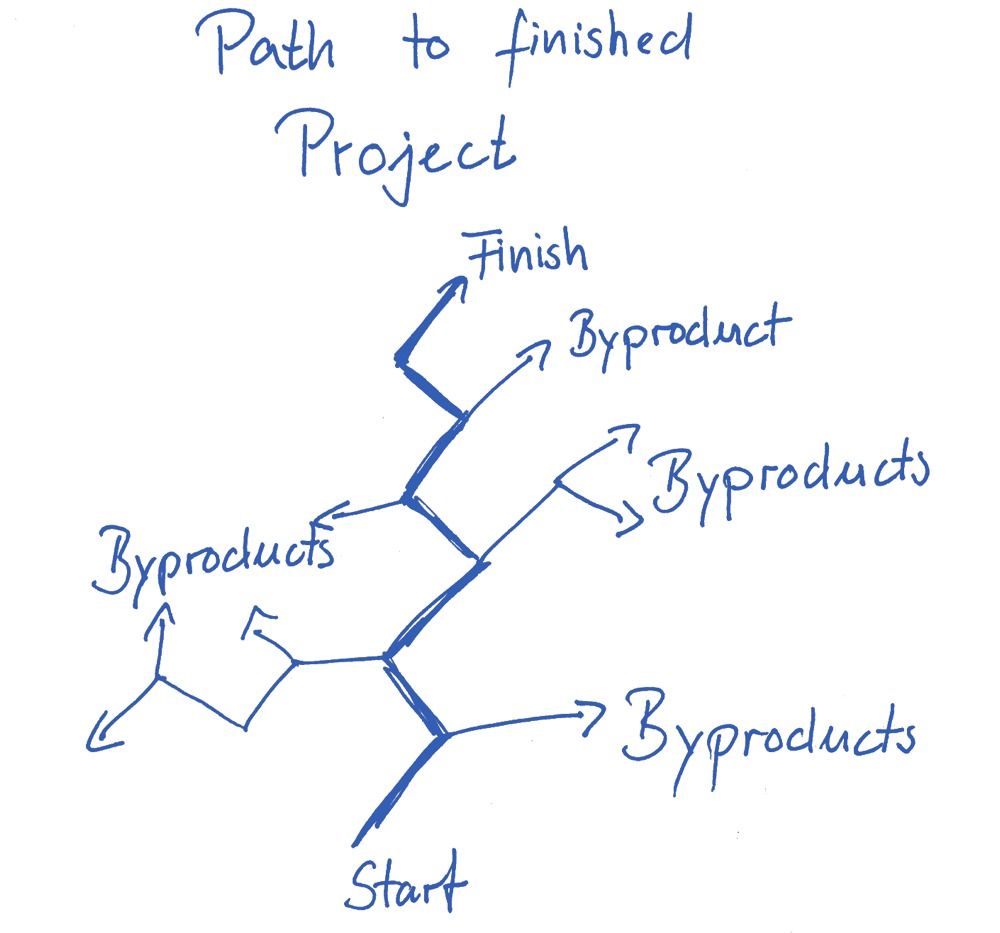

In practice, you need to compromise between taking extensive notes and focusing on your current project. You can't just jot down what interests you and expect to get something out of it. So, use your current project as the main line to guide your work, while allowing a little deviation from that line. The degree of deviation depends on your deadline.

The benefit of this habit is that you can maintain smoother writing. In technical work on another project, I wrote countless great ideas and articles. Keeping your flow state will result in more useful ideas and words in the long run. The limitation of this practice is how many tasks you need to accomplish in a short period of time.

These by-products are not waste. In the long run, they will be valuable knowledge for your future projects. Furthermore, they form links with the rest of your Zettelkasten and will enrich your personal learning experience when using Zettelkasten.

I have a long term book project. This is a very comprehensive nutrition book that is part of the Healthy Living series. One chapter is devoted to how to incorporate nutrition into other areas of responsibility: stress, training, daily life organization, etc. I let it go and I ended up writing an entire book from this chapter.

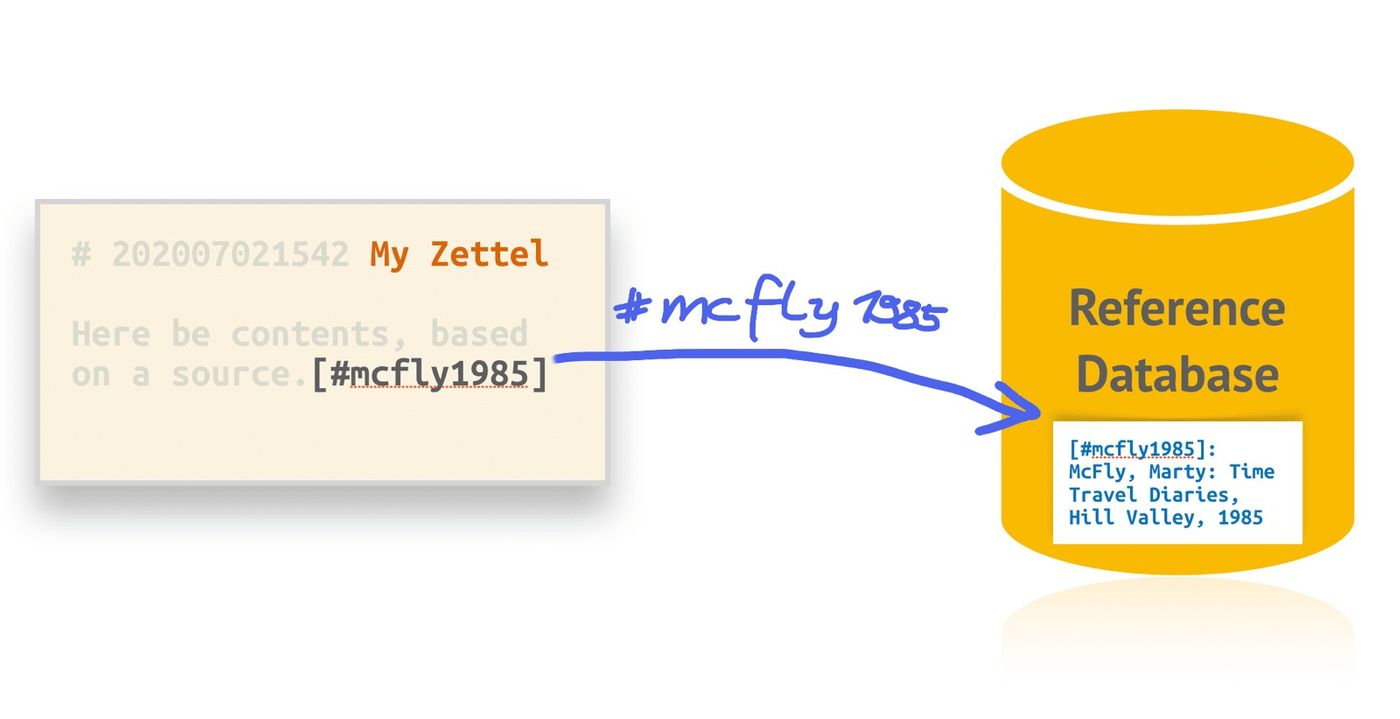

Reference

The citations section at the bottom of the Zettel states where the information came from. A footer is an appropriate place for external resources such as books or web articles.

To manage references, use reference management software like BibDesk. It will contain bibliographic data and give you citekeys. Citekeys are similar to IDs. They are identifiers by which you can point to the reference you are using (a common citekey format is [#lastnameYEAR]).

However, sometimes you will use other Zettel as your inspiration. In this case, your thinking is based on what you have dealt with in the past. You can reference it by linking to Zettel by ID, linking old and new.

If you don't have references at all. In this case, you don't need to do anything in this references section. If no references are given in a Zettel, then the default is your own idea.

stitched together

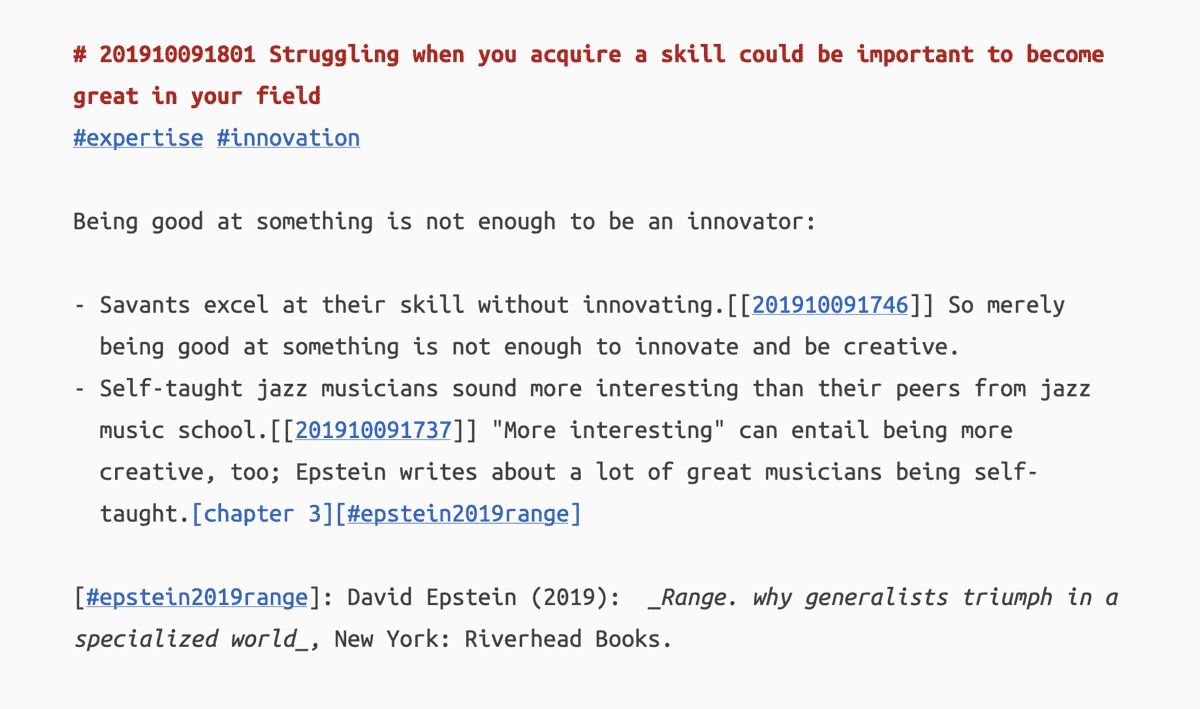

Looking at this picture, all the elements are pointed out.

So far, we've only looked at a single Zettel. Now, let's look at the relationship between Zettels.

Connect Zettel

The real magic of the Zettelkasten comes from the strong emphasis on connections compared to the average note-taking system. Every new Zettel needs some kind of relationship with another Zettel. Luhmann further emphasized the importance of connecting each new Zettel:

If there are several possibilities, we can solve the problem as we wish, just record the connection by link (or reference). Often the context of our work implies multiple connections to other notes. […] In this case, it is important to capture the connections radially […], but also immediately record the [backlinks] in the slips that are linked to (backlinks). In this working program, the content we notice is often enriched as well. (From "Communicating with Slip Boxes")

The main benefit of connections is their effect on you and your brain: when you connect pieces of knowledge with other knowledge, you create relationships between the pieces of knowledge. Knowledge relationships can significantly improve memory, and the relationships formed also train your brain to see patterns.

Let's say you read an article about anthills and think, "Wait a minute. This looks like the organization of a factory I own!" You draw a lot of the similarities between the factories you see and the anthills place. Why are you seeing these connections? You see them because there is a typical pattern that describes both an ant colony and a factory. Some may contain more than you know: assumptions about the unknown. Will there be particularly efficient paths in the ant nest, and you can similarly tweak your plant layout to make it work more efficiently?

When you connect, you will learn, understand, and thus expand yourself in two ways: (a) your knowledge will increase, and (b) you will become a better observer. By becoming a better observer, you will be able to gain more insights from your observations. More universal patterns will emerge and become more obvious to you. A fundamental aspect of working like this is that it allows you to enter a general mode of reality.

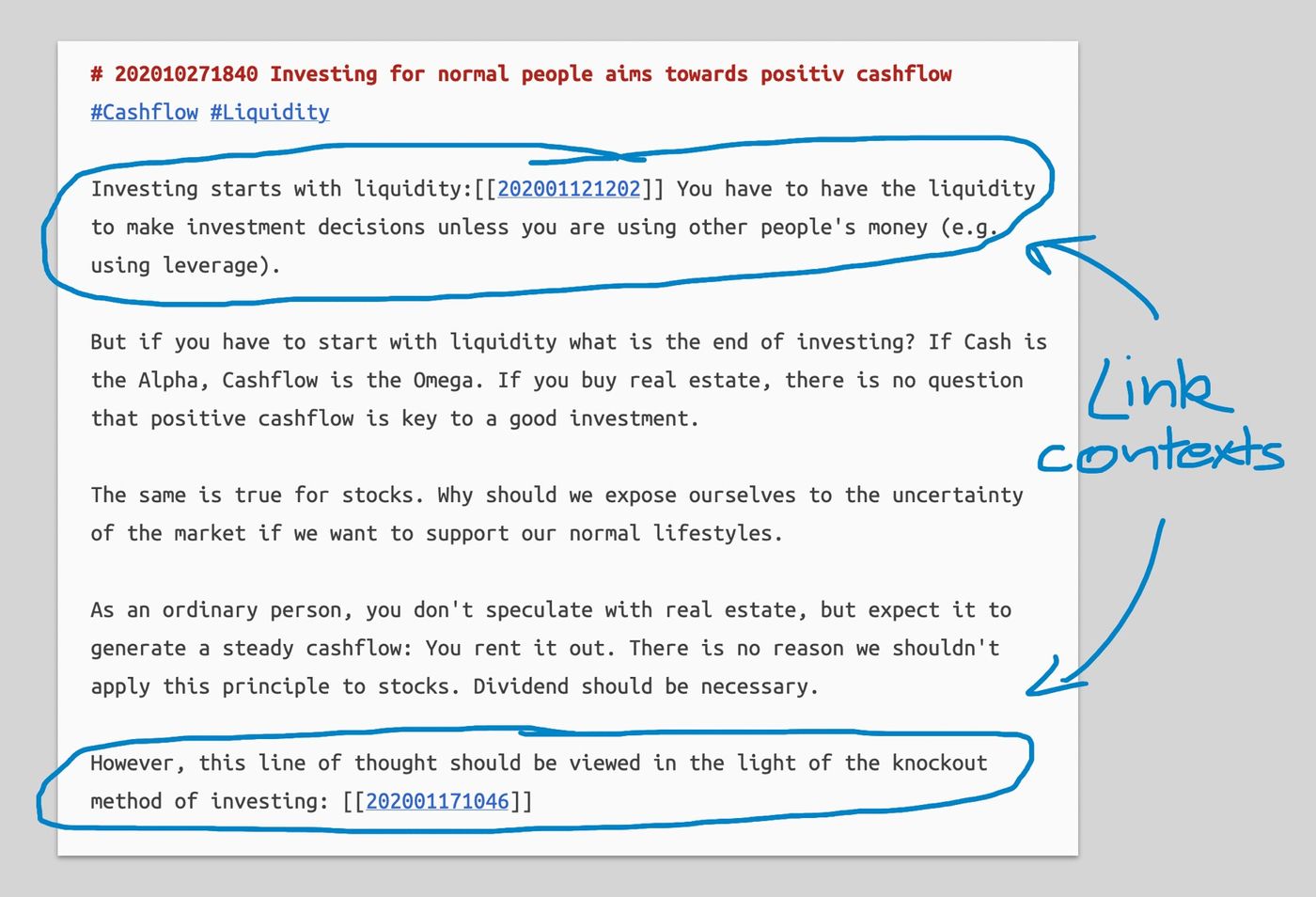

To get the most out of this connection, be sure to clearly state why you're making this connection. This is the link context. An example of a link context is shown below:

The first paragraph adds context to the link. The link cites a note explaining why if you start investing, liquidity needs to be a priority. The link context is the explanation after the link itself. I explained to my future self what would happen if he would follow this link.

This connection is one of Zettelkasten's main knowledge-creation mechanisms: the meaning of the connection, the reason for the connection, is clear. To be explicit about why is to create knowledge.

If you just add links without any explanation, you are not creating knowledge. Your future self doesn't even know why he's following the link. One might now think that these links were placed for good reason. However, if you have created a web of thoughts and you cannot be confident that following a link will lead you to something meaningful, then browsing your own thoughts will give you a sense of disappointment. Your future self will judge your past self (you!) to be unreliable.

In conclusion, gathering connections without a clear intent, without a captured statement of meaning or relevance, is not knowledge production, and as a habit it can even be counterproductive: you make superficial work a habit, and Thus reducing your skills as a creative knowledge worker.

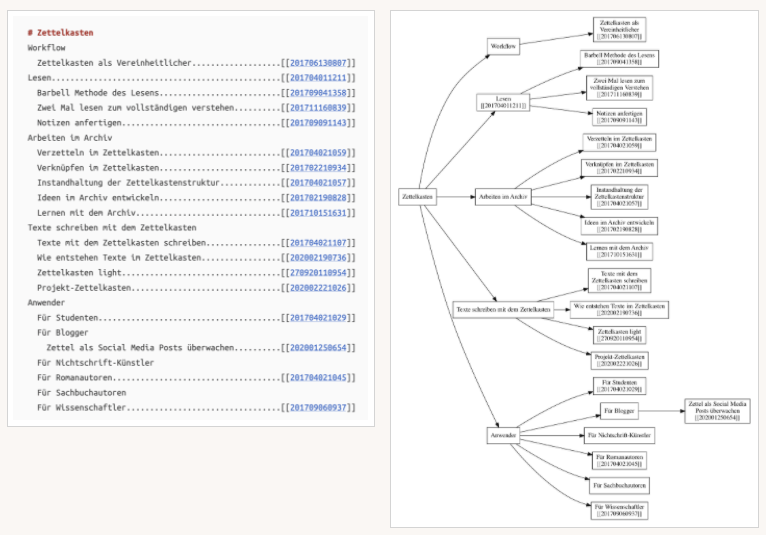

Structure Note

A Zettelkasten should not only be a web of ideas you create from the underlying Zettels and their connections. Some kind of hierarchy is very useful. Luhmann himself needs to address this issue.

We can see how he uses his register. Not every relevant Zettel is listed for every keyword. Only the most central Zettels are the entry point of a theme.

In addition, Luhmann has hub notes . These Zettels list many other places where a continuation of a topic can be viewed. Luhmann's Zettelkasten presents a serious challenge to finding all relevant parts, especially compared to digital Zettelkasten.

The main benefit of hierarchy is the increased potential for knowledge creation. Structuring your knowledge is a very productive way to get you more information. Let's explore "The Structure Note" as it is one of the ways to add structure to a zettelkasten.

A Structure Note is a Meta-Note : it is a Zettel about other Zettels and their relationships. Luhmann's hub notes are a quick way to browse the web of notes. The same goes for Structure Notes. For example, I have a Structure Note on the Zettelkasten method. It's kind of like a catalog of all my Zettels on the subject. Whenever I write a new Zettel about a Zettelkasten method, I make sure that on this Structure Note, or on the Structure Note referenced by the main Structure Note of the Zettelkasten method, put a link to it.

Another Structure Note of mine is about general models . Each Zettel records an independent schema about various mental models . Two examples are given to illustrate:

- Obstacle model . It is generally accepted that transitioning from one state to another requires an increase in energy output. An example is the phenomenon of starvation. In nature, you need to increase your energy output (hunting or gathering) to transition from starvation to satiation.

- chemistry model . Its gestalt is a molecule made up of atoms. Atoms are parts that are not considered to be divided into smaller pieces. Molecules are the composition of elements. The Zettelkasten method is a model for such an application.

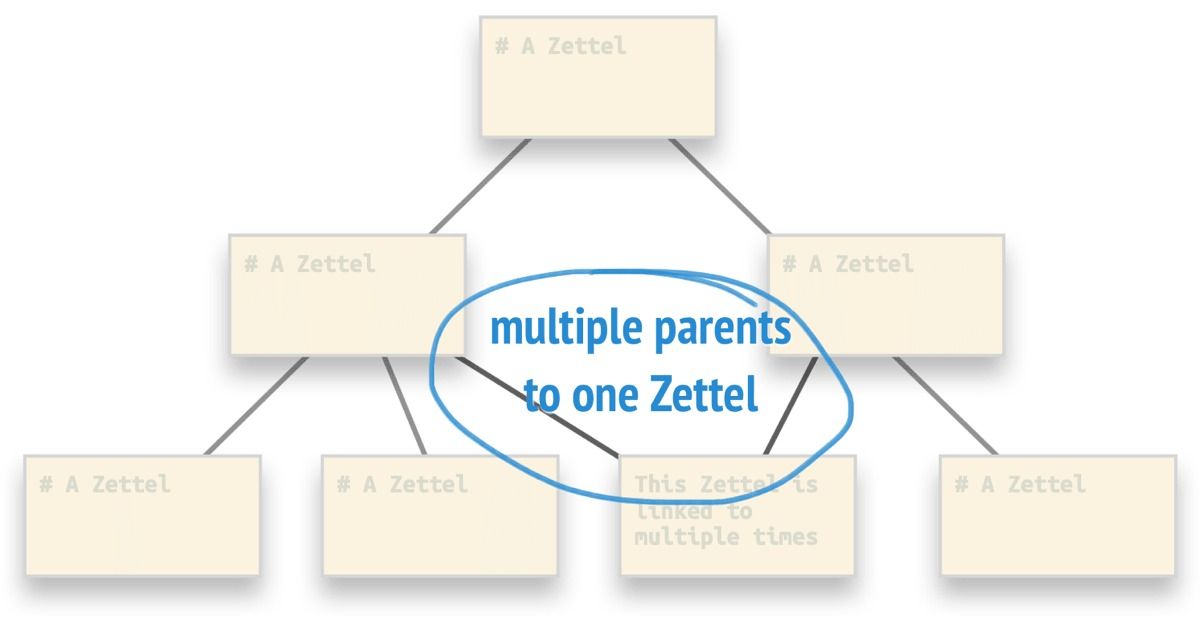

The chemistry model is part of both the Structure Note for the general model and the Structure Note for the Zettelkasten method itself. These coincidences in zettels form a semilattice structure:

In fact, even a half grid doesn't reflect what Zettelkasten really is. The correct schema should be a heteroarchy . But that is beyond the scope of this article.

Structure Notes are not limited to hierarchical structures like the nested lists above. Structural notes can also have sequential structures. Imagine the following argument: a -> b -> c, so a -> c. A Structure Note can capture this sequence and link each step of the sequence to a Zettel, which Zettel extends.

in conclusion. Create Zettels about relationships between other Zettels, known as Structure Notes. The practice of creating Structure Notes will further train your ability to deal with general knowledge patterns. Capture the results into your Zettelkasten for later use.

How to implement Zettelkasten?

Choose software

If you choose software to handle your Zettelkasten, the software should have some functionality. Here is a basic list of features you should be looking for:

- The software needed to make hypertext possible. There are two ways to achieve this. You either use whatever linking functionality the software provides—which is often more convenient for the less tech-savvy—or stick to mimicking direct links via full-text search. Search-based approaches become more powerful over time and across applications, but can be harder to get used to. See our demo of how TextMate will handle links. Keep in mind that I have not modified TextMate in any way to accommodate Zettelkasten's processing.

- Navigation between Zettel will depend on two things: full text search and being able to follow links . Full text search is equivalent to finding entry points (obviously more powerful) through the register in Luhmann's Zettelkasten. Links are just links you know. No further explanation is needed. Full-text search is an advantageous option that the digital Zettelkasten has, but the analog Zettelkasten doesn't, which has led to its heavy use.

- A kind of sandbox. An implicit part of Luhmann's Zettelkasten is his desk. He could take out a few Zettel at random and arrange them on the table any way he liked. In the digital version, you can't do that so easily. In The Archive, I use Structure Notes as my desktop. This arrangement is more hierarchical and not as free as a physical note. But it gets the job done.

Paper version of Zettelkasten

If you choose to make your Zettelkasten paper-based, just do it as Luhmann explains in " Communicating with Slip Boxes . "

I started my Zettelkasten journey this way and experimented for a few months. Switching to a digital solution is quite a pain. Unless you have very clear handwriting and can use optical character recognition (OCR) on your notes, or have an assistant transcribe it for you, there is no automated way.

The Archive

One of the main concepts of The Archive is the software-agnostic philosophy and adherence to a simple plain-text approach.

- Software-agnosticism is the principle that you do the opposite of what the software is trying to achieve. There are straightforward ways to frame you, such as storing your notes in a closed file format that no other software can crack. But there are also implicit ways in which you can make it hard to change the software, for example, to make the export process difficult, or to train users to rely on features that aren't available elsewhere. We tried to avoid this, we decided to let the search function do a lot of the work. Even Zettel links come down to search. Full-text search is ubiquitous on computers, so you can reproduce your workflow with almost any plain text editor in the world.

- The plain text approach is a paradigm that uses plain text files as primary storage. Plain text is the most versatile and persistent file format.

In short, The Archive manages a folder of plain text files. You can access your files by performing searches through the Omnibar.

In The Archive, a single Zettel would look like this:

- Zettel's ID is in both the file name and the file content. The main reason is to create redundancy. One use case for this is accessing your Zettelkasten from anywhere: previously, I used Dropbox to access my notes from other computers. Dropbox only allows filename-based searches. So I need to include the ID in the title so I can manually follow the link via Dropbox's search function.

- This ID is time based. It never changes, so you can change the title at will without breaking any links.

- If you follow a link, you will search for the ID within the double brackets. Therefore, you can follow the link with any software that can perform a search. In The Archive, link the ID in double brackets.

- The tag is #. If you click on the highlighted #, The Archive will search for that hashtag. Tags are nothing more than strings that group notes by shared phrases you can search for.

- The Archive uses Markdown to mark up text. It's very readable, and it's also widely used in tools that integrate plain text with publishing methods. Many text editors support Markdown, and you can use other tools to generate beautiful PDF files. The markdown is handy if you want to write an article or do a small demo.

- Citations and book references are added via the extended MultiMarkdown syntax. It interfaces well with BibTeX, a widely supported format for saving bibliographic data in plain text files. Our recommendations for Mac are the open source tools BibDesk and Windows JabRef to manage bibliographic data and connect it to Zettelkasten via the citekeys it produces.

All screenshots here are examples of our Zettelkastens in the archives.

DokuWiki

DokuWiki is one of my favorite software solutions for managing Zettelkasten. If you use DokuWiki, you might consider not having each Zettel have its own wiki page. The DokuWiki user interface is designed to be more suitable for long pages. This violates the principle of atomicity . However, it would be nice if you linked directly to subsections, and each subsection contained an idea. Each page can be divided into sections and subsections, each with its own address, so that each section can be treated as a separate Zettel.

DokuWiki allows you to use title-based IDs and keep links working when you change title names (i.e. IDs). I still recommend using time-based IDs in addition. They just appear at the address of each website or subsection, but don't get in the way of others. The upside is that you will be able to export DokuWiki to another software (especially text editor) solution more easily. Think of the time-based ID part of the code in Zettelkasten itself, which can be read by various software. If the code is complete, you can use a lot of applications. If you decide against certain parts of the code (conventions), the conversion will be much harder.

In DokuWiki, Structure Notes are just regular Wiki pages. They handle the structure just like the plain text files I described above.

from now on

What can you expect if you follow the Zettelkasten method? Expect more results from your efforts. Do it consistently. You'll probably get stuck at some point, when you can't figure out how to use your tool of choice to implement function X or Y and get things working. As you go through these movements over and over again, when you remind yourself of the basic principles of Zettelkasten, these problems will eventually resolve themselves: you need identifiers for addresses, you need links to create hypertext, and then become confident with practice. Move forward to achieve success in life. So, start doing it. it is necessary. Having a Zettelkasten doesn't make anything easier, but it makes everything possible.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!