Is it a moral duty to help the needy? Questions and Responses to Consequentialism Thesis

"This article was originally published on the public account philosophia on 2020.12.19"

Author / useless

Note: This article was originally a speech. Due to the typesetting of WeChat, it is inconvenient to make detailed notes, but I have clearly stated in the article which scholar or myself a certain point of view comes from. The views of other scholars I reproduced come from me. References listed at the end of the article. Sorry for any inconvenience caused!

1 Introduction

Recently, several members of the Philosophia Philosophy Club initiated and participated in a support education project for left-behind children in Daping Township, Yunnan: " Kafka in the Mountains" . During the process of this charitable work, a parent of a community member criticized: instead of worrying about such distant things, it is better to think about how to help the people around you, and don’t think about things that you can’t control every day. Generally speaking, it is simple to refute this parent: I help the left-behind children in Yunnan and I help the people around me without conflict, and I have the right to choose whether to help the left-behind children in Yunnan. But it also leads me to a further question: Do we have a moral obligation to help them? Because in the general concept, even if a person does not donate after knowing the situation of left-behind children in Yunnan, we don't seem to directly think that this action is wrong and immoral. But some consequentialists don't think so.

The so-called "consequentialism" can be simply understood in this article as an ethical concept: whether the actions we take are correct or not depends on whether the results of the actions can maximize social benefits, rather than on the motives of the actors Or some sacred duty. Strictly speaking, utilitarianism is a branch of consequentialism, and the two cannot be equated, but for the sake of brevity, this article will combine the two together.

The question to be addressed in this article is whether consequentialism has successfully dealt with the "demandingness objection". The so-called "demandingness" means that some things seem to be beyond the scope of obligations, but consequentialism brings this matter into obligations. Classical utilitarianism holds that only the behavior that maximizes utility is a moral behavior. But this kind of behavior may exceed the ability of the individual or the obligation of the individual (there are situations where the individual has the ability but not necessarily must perform it), so the "refutation of demanding" is to raise this point of consequentialism (including utilitarianism). question.

For example, the utilitarian philosopher Singer believed that in promoting the greatest welfare of society, where there is ability, there is also duty. For example, if I am a rich man in the United States, I have a moral obligation to help the poor in Africa. The general morality will think that I don't have this moral obligation. It is my duty not to help, and it is my duty to help. But for Singer, the obligation is absolute.

Some people will criticize that this requirement of consequentialism is unreasonable. In this regard, consequentialists have two ways to deal with it: first, they can say that they have not actually made the above-mentioned unreasonable demands. Second, they can deny that their claims are unreasonable. Most consequentialist approaches to criticism combine these two approaches.

In the face of this response, scholar Mulgan tried to argue that consequentialism is not a strong response to criticism.

Mulgan lists several coping strategies common to consequentialists. First of all, he introduced that the method is an "extremist solution" , a theory that no matter how "draconian" the moral requirements put forward by a consequentialism, it will not be unreasonable, and we cannot If you don't like it, dismiss it as unreasonable. The "extreme solution" argues that if we define unreasonable demands as requiring sacrifices on moral actors that outweigh their contribution to social welfare, then consequentialism makes no such demands at all. For an extremist, such a moral requirement is justified no matter how harsh a sacrifice (such as the entire time and material wealth of the moral actor) is required as long as the sacrifice is smaller than the contribution.

Non-extremism has two other ways to deal with demandness objection. We know that the moral requirements put forward by a moral theory in practice are determined by two factors, one is the structure of the moral theory itself, and the other is the situation in the real world. Therefore, the first method of "non-extremism" is to deny the existence of social needs that require moral actors to make great sacrifices. This is not to deny that there is a great deal of suffering in our real world, but that its solutions do not require great sacrifice on the part of moral actors. For example, the best way to solve the poverty problem in the third world is not to let the developed countries donate money to their own abject poverty, but another way.

The second method of "non-extremism" is to reconstruct consequentialism. Such consequentialism does not always require the best result (some consequentialists think that it is enough to get a good enough result, and some consequences One is that we should consider the preferences of actors, and the one that will be introduced later is that actors do not have to make decisions with the goal of maximizing benefits).

Many consequentialist strategies to deal with demandness objection are to combine the above three methods. Specifically, they try to correct our concept of "reasonable moral requirements", redefine consequentialism's requirements for results, and put this outcome theory into reality. social reassessment. In this paper, Mulgan will refute the above three methods.

2 Responses to "extremism"

First of all, Mulgan wants to refute "extremism". Extremism holds that moral theories that make extremely demanding moral demands are not necessarily irrational. They profess several non-contradictory moral principles:

1. The principle of increasing benefits: As long as an action can bring about valuable or good results, then it provides a reason for practicing it. If we choose actions solely for the purpose of bringing about benefits, we must choose the actions that lead to the best outcomes.

2. The principle of avoiding evil: If our actions prevent evil from happening without sacrificing other things of equal moral importance, then we will do it.

3. The principle of helping the innocent: If we can extend a helping hand to innocent people who are in dire need of help, and the cost we pay ourselves is negligible relative to the benefits of our help, then we will do it.

These three principles are accepted by consequentialists and many opponents of consequentialism.

These three principles serve as a starting point, and the next step in the argument of an "extreme" consequentialist is to test and reject all intuitions, principles, and arguments that deviate from this starting point. If these three principles are not restricted, then the "harsh" moral requirements proposed by consequentialism will be reasonable.

Consequentialists object to intuitions that deviate from these three principles. First, Peter Singer proposes a " conscience stimulation strategy" : if (1) people are well informed; (2) are clearly given reasons; life, then they will no longer think that the moral requirements given by consequentialism are unreasonable. Consequentialists who embrace this strategy claim that moral theories should agree not with people's actual intuitions, but with idealized intuitions—where people's consciences are properly aroused. Therefore, whether certain moral requirements that are intuitively "demanding" are reasonable must be tested by this ideal state.

Consequentialist Peter Unger questions some intuitions with a thought experiment. He believes that the traditional moral philosophy thought experiment with only two options actually makes us ignore the various conflicting moral intuitions about "kill one save many" in some cases. In the traditional two-alternative thought experiment, our moral intuitions about the consequentialist and non-consequentialist options seem to be certain and clear, but Unger thinks they are not. He envisioned two scenarios. In the first scenario, sixty people got the plague. If I left them alone, they would die in a few days. Now there is an innocent person who has some kind of antibody in his body. Now save the sixty people. The only way for the individual is to cut off the innocent man's foot, squeeze the juice and inject it into the sixty people, and they will be cured, in which case most people will refuse to cut off the man's foot. The second situation is the traditional tram problem. Kill one and save six or let the tram run over six people. In this case, most people will choose to kill one and save six. In these two cases, according to the principle of maximizing the benefits of consequentialism, the benefit of saving 60 people is far greater than that of saving 6 people, and the loss of cutting off a foot is far less than killing a person, but most people (the same group of people) Moral intuition still refuses to cut off the feet and chooses to kill one and save six. The explanation given by Unger is that in the first case we seem to be actively using the innocent person, but in the second case we are forced to choose between two options. But the choice in the first case obviously violates the consequentialist principle followed by those who choose to kill one and save six in the second case. Therefore, Unger imagined a situation that can combine these two situations, which forces us to jump out of the narrow two options and rethink our moral intuition when facing various choices, and we will find that the intuition is in line with consequentialism.

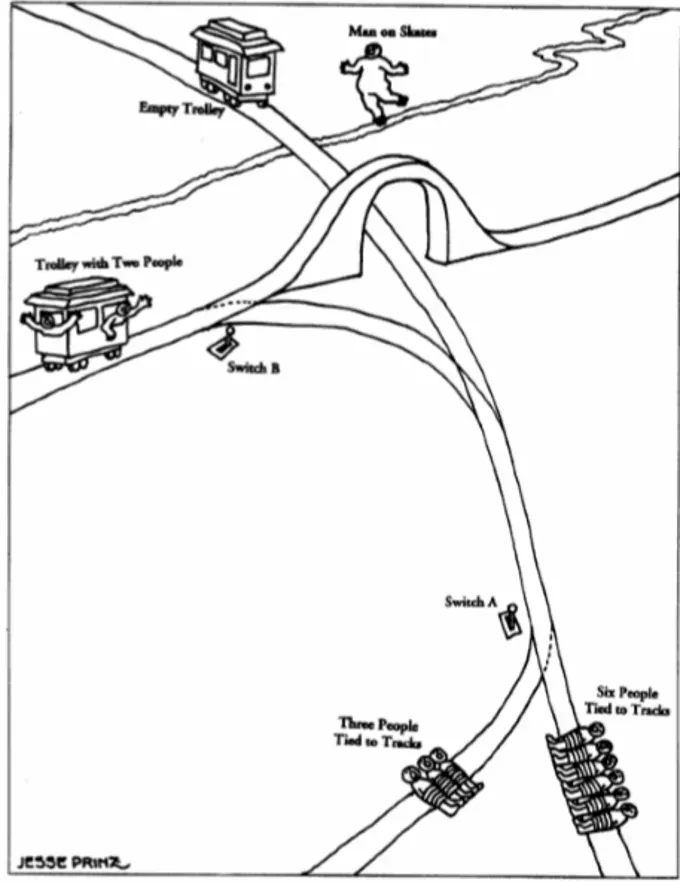

This situation is an advanced version of the trolley problem (pictured below): Now there is an unmanned, heavy trolley A (pictured above) that is about to drive to six innocent people who are tied up. There is a switch A (below the picture), if I press switch A, the trolley will go to another track and run over three innocent people.

Option 1, if I do nothing, all six of them will be run over.

Option 2, I press switch A, kill three and save six.

At the same time, on the way of tram A, there is a light tram B (on the left side of the picture) with two people on it, and there is switch B (on the left side of the picture), press switch B, tram B will be on tram A If you collide with tram A before driving to the track controlled by switch A, the two trams will derail, and the two innocent people on tram B will die. If switch B is not pressed, trolley B will pass safely on the bridge above tram A, but the six people on the rails will be run over by tram A to death.

Option 3, I press switch B, kill two and save six.

There is a stream across the track in front of Tram A, there is a fat man (on the top of the picture) skating on the stream, push the fat man onto the track, Tram A will run over the innocent fat man, and then stop, otherwise It will crush six people to death.

Option 4, I push the fat man in front of the tram to block the tram, kill one and save six

In such an option, one would find the choice made by consequentialist intuition, option four, acceptable. Because, the person who wants to follow the intuition of non-consequentialism will find that option 1, the complete non-consequentialism option, to kill six people, is unacceptable. And from Option 2 to Option 3 is a progression in which the consequentialist intuition is more and more preferred but the non-consequentialist intuition is more and more annoying (because the initiative of moral actors seems to be getting higher and higher), but the intuition also seems to be Will slowly lead most of us to the fourth option, although actively killing a person is far more damaging than cutting off a person's foot. Let me personally understand that the four options are divided into two parts, option 1 and option 2 seem to have a weaker moral actor's initiative, and option 3 and option 4 seem to have a stronger moral actor's initiative. If the actual conditions only provide us with two options within the two parts to choose from, for example, let us only choose from one and two, or only let us choose from three and four, then what we are facing at this time is a Classic trolley puzzle situation. But if we choose one option from each of the two parts to combine, for example, we can only choose from option one and option four, then we seem to be facing a situation of cutting off the foot to treat the disease. However, in many moral choices in real life, these two situations are combined, that is, the situation where non-consequentialist intuition is dominant and consequentialist intuition is dominant. Then through this advanced version of the trolley problem, it seems that more people will be biased towards consequences. doctrine intuition.

In conclusion, I think Unger seems to be saying that non-consequentialist intuitions may be strengthened when we only think about a moral situation with two choices, but if we compare different situations in relation to each other, we will rediscover that It seems that the intuition of non-consequentialism is suspect.

We return to Mulgan's argument. Mulgan next introduces a second strategy for "extremists" to deny nonconsequentialist intuitions. This strategy rejects all moral intuitions that are not supported by sound arguments. If our moral intuitions come only from evolution or cultural tradition, then they are unreliable. And there are many non-consequentialist intuitions that are not fully demonstrated.

Mulgan believes that the above-mentioned consequentialists' strategy to deal with demandness objection is unfair. First, their starting point is not necessarily reasonable, and second, the standard of what is a good argument is established by themselves rather than generally accepted. The three principles that Mulgan sees as the starting point for consequentialists themselves appeal to intuitions, and these intuitions are no stronger than those of non-consequentialists. For example, it is undeniable that most people feel a far greater moral responsibility to save a child who is drowning in front of them than they do to save starving children in ten other countries. The intuitive reliability of the consequentialists' starting point itself is questionable. Some temperance theorists oppose the principle of increasing benefits. My personal understanding is that they believe that some benefits do not come from the intention to increase benefits at the beginning, but from the trade-off in action itself. For example, in Smithian economics, those selfish, Rational economic activities just increase the benefits of society as a whole. Therefore, the intuition of consequentialism does not seem to be that strong, but consequentialists require that the intuition of non-consequentialism is strong enough.

Another key problem Mulgan sees is that consequentialism often attempts to deduce general moral principles from a specially constructed simple story, and very biased interpretations constitute the legitimacy of general morality. That is to say, the grounds for their legitimacy are often but ones of consequentialist preference (whether intuition or thought experiment). For example, the consequentialist philosopher Singer gave an example: a person walks to work in the morning, is about to be late, and passes a child who drowned in a pond. This man can save the child, but at the cost of wearing a wetsuit and losing a few minutes. Singer believes he has a clear duty to save the children. But this is clearly a very consequentialist example. Drowning children may have a very limited responsibility, or this responsibility is only effective in very limited circumstances, but Singer regards this limited responsibility as a general moral legitimacy. However, the author believes that if the situation in this example is replaced by me exchanging 20 years of my own life for 30 years of that child’s life, this is in line with the principle of consequentialism, but if we think that this can become a moral obligation, I believe I don't think most people would agree.

Thus, Mulgan argues, constructing a complex story with multiple options does not necessarily lead to consequentialist intuitions or inferences. Mulgan's own surveys in his undergraduate classes show that many people don't share an intuition with Unger, and it's entirely possible for people to gravitate toward non-consequentialist intuitions in a complex story with multiple options. In the recent history of moral philosophy, it seems that consequentialists have failed to convince those who were already skeptical of consequentialism to agree to the "principle of increasing benefit".

A fourth problem for extremists, according to Mulgan, is that they need to clarify what exactly the consequentialist claim is. If consequentialism requires me to donate all my property to help the poor under the premise of maximizing social benefits, this may not be so unreasonable in the eyes of some people. But if extremists want to justify some impossible requirements of consequentialism, such as I want to die for the sake of maximizing social interests, or be ruined by serious misunderstanding, or destroy everything I cherish with my own hands, then there is a problem. If a person's life, reputation, and all that is valued can be reasonably claimed by universal moral obligations, then there seems to be no unreasonable moral claim. Either extremists give a strong enough argument to argue that this is reasonable, or they admit that sometimes some demands for moral obligations can be denied, and many extremists choose the latter.

3 Negative strategies

Some consequentialists argue that consequentialism does not, in practice, require substantial economic contributions or self-sacrifice from moral actors, since in reality caring for yourself and those around you tends to lead to better outcomes (we It may be that we understand the needs of ourselves and those around us better, or we are more naturally inclined to love ourselves and our loved ones psychologically, etc., which will be explained in more detail below). But Mulgan finds this argument unconvincing. Mulgan will try to argue that, in practice, some harsh moral requirements cannot be avoided if the principles of consequentialism are followed.

The "ignorance of benefits" problem:

Some consequentialists argue that because we know more about the benefits we want in ourselves and those we are close to than we know about the benefits that people on the other side of the world want (given their political, economic, and cultural conditions) We are very different), so if we focus on the benefits we know about, we will increase returns more than if we dream about benefits we don't know about.

Mulgan's counterargument to this claim is that, first of all, while we don't fully understand the conditions of the poor in Africa, we do know they need clean water, enough food, etc., and we can really help. We can fully understand those universal basic human needs.

The "ignorance of consequences" problem:

Consequentialism calculates the value of an action by multiplying the probability of taking the action by the benefit if the action is successful. In this way, the value of donating a large amount of money to the poor in Africa is weakened in the view of consequentialism, because the money I donate is likely to be embezzled by local African warlords. Indeed, it is difficult for us to predict the consequences of these actions, but Mulgan pointed out that we can still donate money to charitable organizations like the "United Nations" that have clear predictions about the consequences, and let them help us do good. In addition, I think we can resort to the media to draw attention to related issues, which sometimes requires a lot of effort. And is it really harder to find a way to get an extra bottle of clean water for the poor in Africa than to find a way to help yourself, your family and your friends in your life? I donated "10,000 yuan" to feed the poor in Africa, and spent "10,000 yuan" to the study abroad agency so that I can go to the Ivy League for graduate school. I believe that the former has a greater possibility of achieving what I want. result.

Here Mulgan reminds us to distinguish between consequentialism based on factual consequences and consequentialism based on possible consequences. Mulgan designed a thought experiment: Now there are two buttons X and Y in front of Xiao Ming, and when the X button is pressed, there will be a 1% probability that a person will be electrocuted to death. Conversely, pressing the Y button has a 99% chance of electrocuting a person. Now Jim presses the X button, and by tragic accident, an innocent person is electrocuted. Consequentialism based on factual consequences will think that Xiao Ming's pressing X is a wrong choice, and he should press Y. But consequentialism based on possible consequences would think that Xiao Ming's pressing X was the right choice.

The second distinction is consequentialism based on subjective possibility and consequentialism based on objective possibility. Going back to the situation just now, now Xiao Ming is deceived by someone. He mistakenly thinks that pressing X has a 99% chance of innocent people being electrocuted to death. When he presses Y, the chance of innocent people being electrocuted is 1%. The reality is the opposite. Xiao Ming chose to press Y, and an innocent person died in response. Then the consequentialism based on objective possibility will think that Xiao Ming's choice is wrong, because pressing Y is actually more likely to electrocute people. But the consequentialism based on subjective possibility will think that Xiao Ming's choice is correct, because Xiao Ming thinks that pressing Y is the most likely to save the innocent person.

Mulgan argues that if we make these two distinctions clear, we can avoid a lot of confusion and confusion. I personally think that the requirements of a reasonable consequentialism for moral actors should be based on possible consequences and subjective possibilities. Because the factual consequences and objective possibilities are not fully grasped by any actor in advance, for example, according to the factual consequences, strangling Hitler when he was a baby may have saved many people from dying, but we cannot condemn that Nurse delivering Hitler in the 19th century. Each of us can only act according to the possible consequences and subjective possibilities, so consequentialism should not use the reason that "the warlords may embezzle your donated money" to oppose us donating money to the poor in Africa, after all, it is based on subjective possibilities sex, it seems more likely that the behavior of donating money will help the poor.

Matter of importance:

Some consequentialists believe that we can't really help the poor far away. We may be able to keep them alive temporarily, but we can't bring about a fundamental change in their living conditions. So consequentialism does not ask people to do such futile things.

Mulgan’s counterargument is that, first of all, our donations of food and water are significant enough that they can at least sustain life, which is worth living in itself. And second, second, a dollar we spend on poor people in Africa has more worthwhile outcomes than spending it on us. What Mulgan said here is not very clear. My personal understanding is that it is also "200 yuan". I will use it to buy shoes, and the "200 poor people" in Ethiopia will use it to buy clean water. Under normal circumstances, The same "200 yuan" will bring more happiness to the "200 poor people who buy water". Moreover, it is clear that my spending "200 yuan to buy shoes" will not bring any fundamental change to my living conditions. On the other hand, in general, the purchasing power of a dollar in poor countries is higher than in developed countries, so for the same dollar, poor people in Ethiopia get more than me. So according to the general consequentialist view, it is reasonable to help the poor in Africa.

Malthusian problem:

Some consequentialists who want to deal with the demandness objection argue that, according to Malthusian theory, our help to poor countries would allow more people to live to adulthood, which would lead to a population explosion due to high fertility rates in poor countries and lead to massive Child deaths, so in the long run consequentialism does not require us to help people in poor countries.

Mulgan's answer to this is simply that a great deal of empirical and statistical evidence shows that Malthus was completely wrong. An improvement in the quality of life will reduce the fertility rate, and even if the fertility rate increases, life expectancy and living standards will increase rather than decrease. From my personal point of view, even if Malthus is correct, these consequentialists cannot deal with demandness objection well, because donating to the poor in countries with "Malthus trap" is only a special case, in other countries, such as birth A developed country with a low economic rate or a China with a strict policy have countless poor people who need help. Therefore, the special case of the "Malthus problem" cannot cope with all strict moral requirements.

Best Global Response:

Some consequentialists pointed out that if everyone agrees with the "strict" moral requirements put forward by consequentialism, and everyone in the world invests a lot of their money and time in charity instead of daily production and family social life, it will cause serious problems. economic dislocation and recession, consequentialism would not treat such behavior as a general obligation.

For this, Mulgan distinguishes between simple consequentialism and collective consequentialism. For simple consequentialism, the best full response problem is out of their scope, because simple consequentialism only cares about individual choices . For that individual moral actor, the actions of other people are like natural phenomena. Concerned about the actions of others within the sphere of influence one can exert. But whether others are influenced by him or not and act with him (of course it is good to be inspired by him), it does not affect his own choice. So things like people all over the world choosing to engage in charity are obviously not within the sphere of personal influence, so simple consequentialism will not consider it. At least as far as simple consequentialism is concerned, the reality is that most people don't invest much in public welfare, so I still have to invest as much as possible for the overall welfare of society.

Then if we shift the focus from individual choice to a collective choice, then it is collective consequentialism , which Mulgan will talk about later.

Alienation problem:

The "rigorous" morality of consequentialism seems to imply that in some cases we should disengage from the tasks of our own lives, abandon the structure of our own lives, and devote ourselves wholeheartedly to the cause of promoting the general welfare of society. Such an alienation seems to be unacceptable to our intuition.

Consequentialists who adopt a negative strategy (that is, the above mentioned that consequentialism can deny the obligation of people to make huge sacrifices for the overall welfare of society in some cases without violating their own principles) distinguish two kinds of alienation. The first kind of alienation is to alienate one's original life and devote oneself to a life for the welfare of society as a whole. The second kind of alienation is that I am not deeply involved in any kind of life. Simple consequentialists would argue that their theory is alienation of the first kind, that is, not real alienation, but moral actors constructing new lives for themselves around public good or political engagement, and simple consequentialism allows moral action as well Consequentialism does not completely ignore the happiness of moral actors themselves, since they choose the one they enjoy more when the benefits they contribute to society as a whole are equal. But it is difficult to convince those opponents of consequentialism, after all, consequentialism requires that the most important motivation for our actions is to maximize social welfare.

Mulgan argues that the question of alienation is very powerful against consequentialism. If we really use the maximization of social welfare to set the goal for our life, then in the changing social conditions (imagine you live in China from before 1949 to after 1990), the best way to maximize social interests is If the best method is constantly changing, then we must always be ready to completely change and abandon the way of life for the needs of the social good. Not everyone can have this consciousness.

4 Reconstructing Consequentialism

The previous attempts have shown that it is difficult for us to defend simple consequentialism, so it is necessary to reconstruct consequentialism. Mulgan will point out that the reformulation of consequentialism does not allow consequentialism to successfully face attack.

Mulgan started by re-examining simple consequentialism. First, he believed that simple consequentialism has the following principled features:

First, actor neutrality: This refers to the tendency to value actions from the perspective of the individual amoral actor. Different actors are given different preferences, commitments and interests with the same weight in the value judgment. For example, if I save a relative A or a stranger B, simple consequentialism tends to ignore the subjective emotions of the actors when judging the value of these two actions, but judges the value of saving A and B purely from the perspective of society as a whole value difference.

Second, maximization: Actors should pursue the best outcome, or the greatest expected value.

Third, individualism: simple consequentialism focuses on the specific actions of specific individuals rather than a general pattern of behavior among a group of people.

Fourth, immediacy: the action with the best outcome is the best action, not the action established by some "best rule".

Fifth, focus on action: Simple consequentialism is concerned with assessing the value of actions, rather than assessing rules, psychology, motivation, etc.

Starting from these five principles, Mulgan introduces some variants of simple consequentialism:

The first variant: a modification of the agent-neutral principle, which introduces the individual preferences and views of the agent into consequentialism. This might make consequentialism seem less demanding.

The second variant: Changes to the principle of maximization, for example, as long as the result of the action is good enough, it does not need to be the best forever.

The third variant: For the change of individualism, this is the collective consequentialism mentioned above. The most representative of these is rule consequentialism, which requires people to follow a series of rules, which can achieve the best results if these rules are internalized into a group behavior pattern.

The fourth variant: a change to the principle of immediacy. The evaluation of value by rule consequentialism has changed from the evaluation of the value of direct actions to the evaluation of the value of rules. Although Mulgan's example here alters both the immediacy principle and the individuality principle (since rule consequentialism requires an evaluation of the group's behavior patterns regulated by the rules), there are also consequences that alter only one of the two principles doctrine variants. Changes to the principles of individualism and immediacy are not necessarily bound together. For example, some consequentialisms that only alter the principle of individuals consider the value of every action performed generally in a group (as opposed to actions performed by only a few individuals), while others that alter only the principle of immediacy consider the value of an individual It is better to follow the rules you have developed or accepted in your own life (in short, personal habits) than to follow other rules.

The fifth variant is a change to the action-focused principle. Multiple consequentialism takes into account the different motivations, psychology, virtues (such as bravery, humility), etc. held by the actors leading to the same outcome in the valuation. It should be noted that multiple consequentialism is distinguished from indirect consequentialism, which treats action consequences, motivations, virtues, etc. equally, but for indirect consequentialism, it prioritizes the value of rules .

One thing I personally want to remind is to distinguish rule-consequentialism from deontology. Deontology believes that a certain rule is worth following because it is good in itself, while rule-consequentialism is because rules can pass norms. A group's behavioral pattern serves a good purpose so it is worth following. Let me give an example that may not be appropriate. We imagine a matrix-like world. The world virtualized by computers is beautiful, but the real world is cruel. If a person who discovers the truth of the world tells others the truth, it will destroy them. Happiness. Then I think rule consequentialism would come up with the rule that no one who finds the truth can tell the truth, because that would destroy the overall happiness of society. But deontology will require those who discover the truth to tell the truth, because the truth itself is the absolute good.

For reasons of space, we will temporarily put aside how Mulgan criticizes the amendments to principles 1-3, and focus on the amendments to principles 4 or 5 cannot help consequentialism deal with demandness objection.

5 Distinction between standards and procedures

Mulgan then introduces a strategy of revised consequentialism that combines indirect consequentialism and multiple consequentialism, based on the distinction between criteria for judging correctness and procedures for making decisions. strategy has been criticized.

Mulgan believes that the core question of moral philosophy is: How should an actor decide what to do? The answer is: follow the best process for making ethical decisions. The procedure recommended by consequentialism, then, seems to be: actors always seek the best outcome. But procedures for making moral decisions that some argue point to the best outcomes do not seem to necessarily lead to the best outcomes of moral action. A best course of action does not necessarily guarantee that you have adopted a decision procedure that leads to the best outcome. That is to say, the criteria for judging the quality of an action are separate from the quality of the decision-making process for making the action. For example, some consequentialist theories believe that a person follows a consistent moral decision-making process formed in her specific personal life experience, and may not achieve the best result when she takes a certain action according to this process. But this may still be the objectively best decision-making procedure, because the overall benefit she can achieve by following this procedure to make a lifetime of moral decisions is greater than if she discards her existing moral beliefs every time and then fundamentally recalculates How to achieve the best outcome (I personally think this may cause her to hesitate, waver, confusion, etc. when making moral decisions).

Mulgan argues that this distinction raises three questions: First, under what circumstances are the criteria for judging an action good or bad and the criteria for judging the decision-making process that led to it separate? Can they be separated only in theory or in practice? Second, some consequentialists claim that separating the two leads to confusion among consequentialist actors (imagine you do something for something that you don't think is the best outcome, and you expect the best outcome from this behavior) . Third, can this distinction really solve the demandness objection?

Next, Mulgan will refute the above distinction. He uses a concept "calculatively elusive"-"calculatively elusive". That is to say, the more precise the actor's calculation is, the harder it is for him to achieve the result. Let’s take the analogy of freehand Chinese painting, which can achieve the most valuable artistic effect only when the actor paints unconsciously, so according to the objective requirements of the true best structure, the artist should allow himself to paint unconsciously, but when he When deliberately painting unconsciously for the best effect, it is not really unconscious, and it is impossible to achieve the best artistic effect. That is to say, when a person deliberately wants to go beyond his subjective judgment of the best decision to calculate an objectively best result, it is often impossible for him to do so.

The consequentialists described here by Mulgan seem to be saying that we don't necessarily have to make decisions about every particular action in accordance with our subjective judgment of the greatest good for that action if there is an alternative The procedure implies that we have some kind of objective or overall greatest benefit, and we can make decisions according to another procedure. And Mulgan's counterargument to this is that when we deliberately pursue an objectively optimal result, we often fail to achieve the optimal result. The example given by Mulgan is that a person has to perform a dangerous task. If he is brave and reckless, he has a chance of success. so devastated that it was no longer possible for him to complete the task. But I personally think this example is very strange, because the person Mulgan is objecting to can also interpret this example in the opposite way. When the person performing the task is performing a calm calculation, he is making a judgment on the best result, while His brave and reckless past is the best decision-making procedure-because this procedure will indeed lead to an objectively best effect. So this example seems to be turned against Mulgan. Personally, I attribute this inconsistency to the indistinguishability between the judgment of the best outcome in practice and the adoption of the best decision procedure mentioned by Mulgan above.

Rather than Mulgan's rebuttal, I personally think a better rebuttal is that "subjective calculations of value" and "objective calculations of value" are often not really distinguishable on the part of actors. Most generally speaking, for an actor, he always tends to regard his subjective value calculation as objective, and the so-called "objective value factors" are often incorporated into our subjective calculations to become subjective things, while "subjective value factors" "The factors are often included in the so-called "objective". All in all I think the discussion of the distinction between objective and subjective is ambiguous here, and that's the crux of the matter.

We return to Mulgan's article. The second, calculatively elusive, is when actors are forced to make decisions within a short period of time. For example, when I was about to be hit by a speeding car, I didn't have to think about which jump would be the most likely to survive, but I acted based on my first judgment. In this case, the best decision procedure is not a procedure for calculating the best action, that is to say, people do not need to calculate the best result as the decision procedure at the moment of action. Of course, some people may argue that it is best for me to think in advance that I should act according to my first reaction when encountering such a car accident, so that the judgment of whether the action itself is good or bad still plays a role. But I can change the situation of this example to a completely unfamiliar situation, so that it is impossible for the actor to pre-calculate, at this time the second calculatively elusive is still valid.

The third calculatively elusive mentioned by Mulgan is between friendship and love. It makes sense, if my friend learns that the reason I'm dating him is because it's in the best of both worlds, the friendship will be weird. On the contrary, if he knows that I associate with him because I appreciate him and I care about him, then this is obviously more conducive to the friendship between the two.

I think Mulgan's rebuttal above is odd, don't the consequentialists who try to distinguish between standards and procedures just say that sometimes we make decisions without directly aiming at the best outcome of the current action (as in the car-jumping example and the fraternity example In) calculations can achieve the objectively best results? But Mulgan also seems to understand this discovery of the objectively best outcome as a calculation and a trade-off. But as odd as it is, we can also see the problem with this strategy of transforming consequentialism: when consequentialism attempts to achieve an objectively optimal outcome through subtle means, these subtle means (such as appeals to art) The requirement of beauty or the requirement of emotional love) is essentially in conflict with consequentialism, which is also the fundamental driving force for the consequentialists to propose this distinction, that is, integrity rejection (Integrity objection). That is, when our calculation of the best outcome of a current action threatens the integrity of our lives and conflicts with our boundaries as finite beings, forcing our calculations will not lead to the best outcome. Integrity rejection is fundamentally opposed to consequentialist ethics. Bernard Williams puts it this way: if consequentialists do resort to unconscious, spontaneous calculations of outcomes (the so-called best-of-sometimes decision-making procedures), then it is tantamount to weakening their for the likelihood of making the right action. However, if consequentialists are obsessed with direct calculation of results, such calculations can only be applied in limited situations, which weakens the persuasiveness of consequentialism.

Let's put aside the threat of this distinction to consequentialism itself, and only look at whether this distinction can help consequentialism deal with demandness objection. Can this distinction really make consequentialism less demanding? How many situations do certain conditions meet that would allow one not to pay directly for the best outcome of the action? Even if several people are no longer directly paying according to the most demanding requirements, he may still be asked to pay a lot. The distinction between correctness criteria and decision-making procedures does not necessarily diminish the exactingness of consequentialism. So Mulgan started looking for other strategies.

6 Unblameable Mistakes

Some Consequentialists think they can undercut the exactingness of Consequentialism by appealing to human motivations and natural psychological limitations, one of which is "blameless wrongdoing," a strategy Mulgan would like to point out. Not enough for consequentialists to deal with the "objection to demanding".

The philosopher Parfit proposed "blameless wrong" based on the following example: Ms. C is a mother who loves her child very much. There are now two mutually exclusive options, one in which she confers some benefit to her child, and the second in which she confers a greater benefit on a stranger. Ms. C chose the first option, and she seems not to be blamed.

A consequentialist who accepts Parfit's advice would draw the following three conclusions:

1. Ms. C did not maximize her benefits, so she did something wrong.

2. Ms. C is not to blame because her motives are desirable. Unless her motivations change, she won't make another choice.

3. Ms. C should not be blamed for not changing her motives earlier, because that would have been worse.

Like the previous distinction between correctness criteria and decision-making procedures, the theory of "blame-wrongness" admits that humans are not perfect computing machines, and that some of the motivations for acting are It cannot be controlled autonomously when doing this (for example, Ms. C’s motivation is maternal love, which is not under her own control when she makes a choice). And Mulgan acknowledges that even good intentions can lead to wrongdoing, but that wrongdoing should not be blamed.

To see whether irreproachable mistakes can help consequentialism deal with demanding objection, we need to see whether the case of Ms. C can be compared to the case of the rich in the United States refusing to help the poor in Africa. Some would say that Ms. C is not to blame because her motives are the best - maternal love.

But this point is hard to convince. Is maternal love really the best motivation? Wouldn't it really be better to spend 1,000 yuan less for children and spend 10,000 yuan more for orphans in poor areas?

Therefore, parfit proposed the second version: Now Ms. C has a child and several strangers who fall into the water and cannot swim. She can only choose between saving her own child and saving a few strangers. She chooses to save her child.

The motivational dependence supporting Ms. C's "wrong thing" was something she could not consciously change at the time, which is impossible in natural psychology, so we can hardly blame her for not choosing a consequentialist preference when she made the decision motivation. At the same time, we can't blame her for not developing a motivational dependence of consequentialism preference, because the possibility of facing this life-and-death situation in her life is too small, so the value brought by the motivation of maternal love overwhelms the extremely low probability trigger The predictable value of unbiased motives. So Ms. C is not to blame.

However, Mulgan believes that this cannot be compared with the example of rich Americans and African orphans. After all, helping African orphans is not a sudden bolt from the blue, so they cannot use the example of Ms. C to excuse themselves. However, I personally think that even if Ms. C is in a war-torn country, she faces the trade-off between her own child and other people's life every day, and she chooses to protect her child instead of strangers, then it seems that most of us Still don’t blame Ms. C, this seems to be easier to compare with the example of rich Americans (because both Ms. C and rich Americans make moral choices can be foreseen to a certain extent), of course this example does not seem to be consequentialism preferred.

Some consequentialists argue that we can envision the rich living in an ideal society in which poverty is virtually non-existent, in which it is better to develop a motivation centered on intimacy than on impartiality. But Mulgan believes that the reality is that there is an inseparable relationship between the rich in the United States and the poor in both the United States and Africa, so we should not use this ideal society to compare our real society.

Some consequentialists argue that impartiality motives should not be adopted unless their benefits are emphasized outweighing their harms. For example, a rich man who is required to act impartially on a daily basis may become burnt out and depressed, causing him to stop acting. Therefore a consequentialist should not place too much emphasis on the principle of impartiality. Mulgan pointed out that this problem may be solved through education, so this is not inconsistent with consequentialism. But the psychological issues are complex and he cannot exhaust them in this philosophical treatise. But this reminds us of one point: Does morality have the right to require us to do all possible things within our psychological tolerance? Mulgan believes that morality does not have this power, it should give some of us some breathing space between moral requirements and psychological impossibility. My understanding is that if our morality can only allow us to choose not to follow the principle of consequentialism in some situations that challenge the limits of natural psychology, or always require us to walk on the edge of the limits of natural psychology, this level of demandingness is still relatively high of.

Mulgan summed up Parfit's argument in two points:

1. It is correct that the actors did not consciously change the moral motives they relied on in the past.

2. It is right that the actors do not consciously change the moral motives they rely on at the moment.

Mulgan thinks that the second clause seems more reasonable (we can’t demand that a person suddenly and temporarily change the motivation he unconsciously relies on), but the first clause does not seem so reasonable. I personally understand, for example, why does a person not Consciously educate yourself in life so that the motivation you rely on conforms to the requirements of consequentialism, so that you can avoid the situation that he is now facing unconsciously relying on non-consequentialist motivations.

Finally, Mulgan believes that even if we admit that blameless mistakes do weaken the degree of demandingness of consequentialism in the life-and-death situation of Ms. C's example No. 2, does this really reduce the degree of demandingness of consequentialism as a whole? For example, consequentialism still requires people to give up their hobby of watching movies and donate all the money they spend watching movies. This seems to be a demanding requirement. Blameless wrongdoing does not justify actions that do not seem to have much social benefit, although they form a normal part of a person's life.

In conclusion, the blameless wrongdoing theory does not seem to be able to deal successfully with demandness objection either.

7 epilogue

Finally, we saw that Mulgan refuted the various strategies of consequentialism to deal with demandness objection, but he has not discussed the issue of collective consequentialism in this article. In fact, the modification of consequentialism in terms of maximizing interests and the principle of fairness is still going on. For example, some consequentialisms admit that it is enough to achieve a good enough result, such as Scheffler's actor privilege (acp) or actor Center for emphasis. In short, the discussion on demandness objection is far from over. /

references:

[1] Mulgan, options for consequentialism, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005, p25-p49

[2] Shelly Kangan, The Limits of Morality, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, p11-p15

[3] JJC Smart, Bernard Williams: Utilitarianism-For and Against, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1973, p128

[4] Peter Railton: Facts, values, and Norms-Essays of the Morality of Consequence, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p113

[5] Peter Singer: Famine, Affluence and the demand of Morality , Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2016, p231

[6] RM Hare: Moral Thinking-It's Levels, Methods and Point, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1982, p35-p40

[7] Peter Unger: Living High and Letting Die-Our illusion of Innocence , New York, Oxford University Press, 1996, p85-p90

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More