Creation in the Internet Age (Part 1): Are we destined to have no more great works?

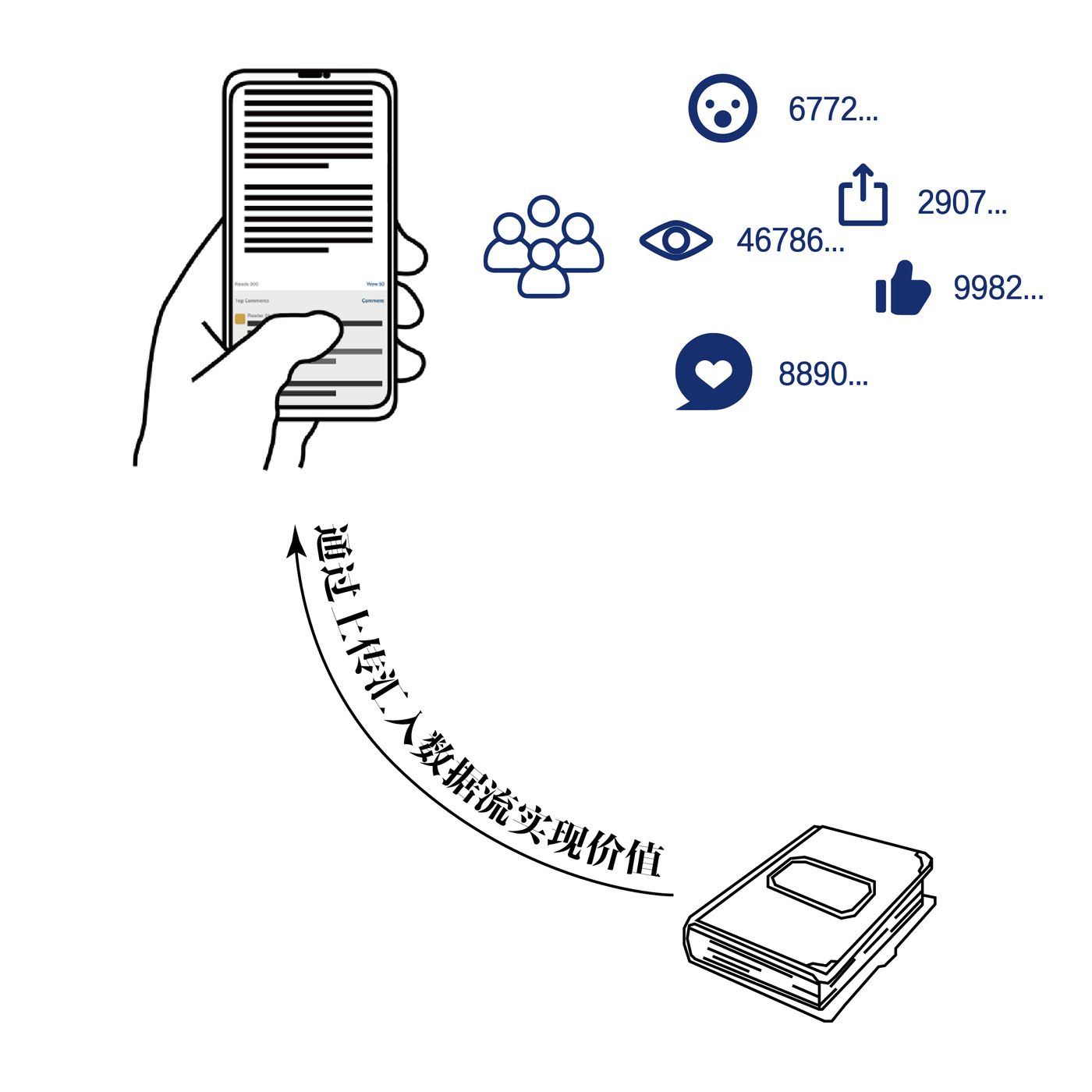

Users who have been online for more than ten years may have similar observations - in the content interface, "numbers" are more and more visible.

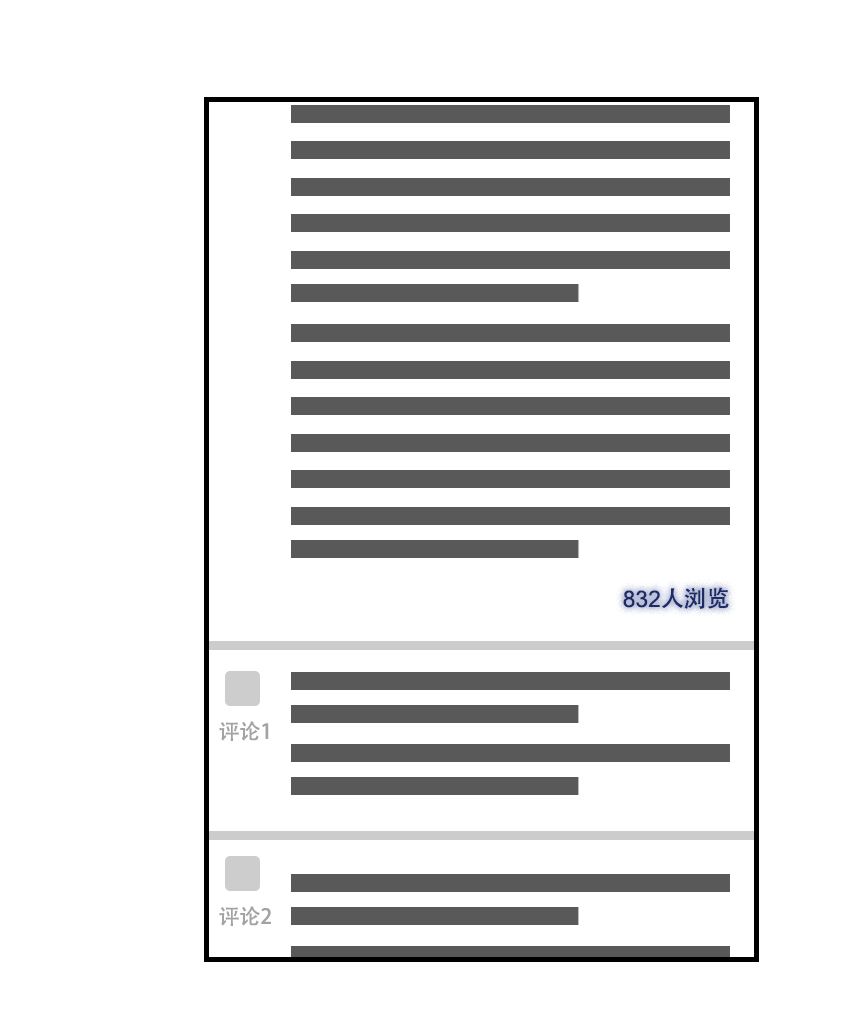

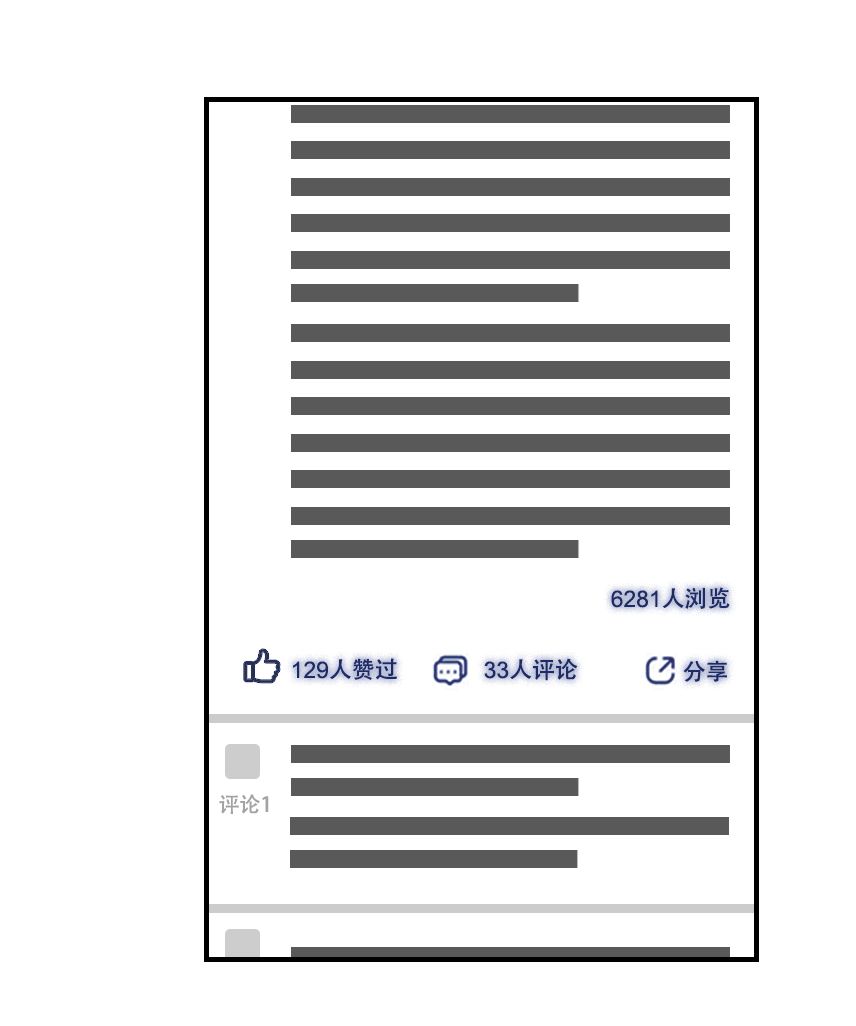

Browsing a blog post in the Web 1.0 era may not see a single piece of data from beginning to end. Gradually, some platforms will mark the total number of reads of an article at the end of the article. After that, the number of retweets and shares can also be seen; after the like function was launched, the number of likes was also added as part of the data expression. There are multiple pieces of data starting at the end of the article.

Today, in 2021, data leaps to the fore in a more radical way.

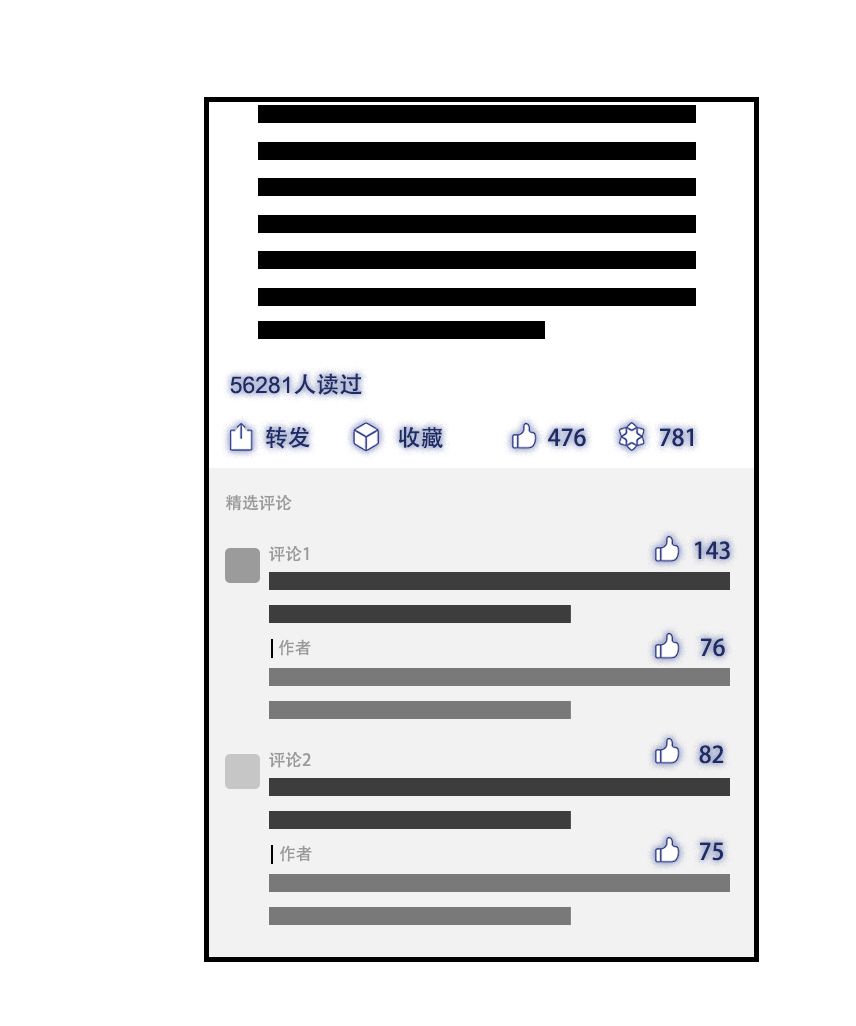

For example, in the subscription interface of WeChat public account, before we click, we can first see how many WeChat friends have read or shared this article. After clicking on the article, the interface will also display the number of people who appreciate it, the total number of readings, the number of likes, and the number of "watching" clicks. In the comment area, we can also see the number of comments and the number of likes for each comment. For the operator of the official account, the data in the background is more extensive and detailed: the amount of appreciation, the number of articles forwarded by other official accounts, the ratio of the number of readings to the number of likes, the reading completion rate, the rising curve of the 24-hour reading volume, New followers after reading this article...

These data in the form of publicly visible numbers have become more and more respected, and they have become the basic unit of measurement by which our digital lives can be quantified. Creating and publishing in this environment is also the keynote of today's online content creation. In this article we do some reflection and self-warning on this situation. Because of the space, we have divided the push into two parts.

The content platform's admiration for data is visible to the naked eye of every user. In fact, this is also called "dataism" by popular science writer Yuval Harari. In "A Brief History of the Future" he talked about this newly coined term and explained that "Dataism" is a new religion emerging in the 21st century. Its teachings advocate that "the value of any phenomenon and entity lies in its contribution to data processing."

If in the Web 1.0 era, the Internet was just an add-on to our lives, today it is taking over our entire lives. With the rise of "dataism", human beings have made a mighty migration from the physical world to the virtual world. This belief has also greatly rewritten today's creative and publishing behavior. Creators need to be "online", and works need to be "uploaded".

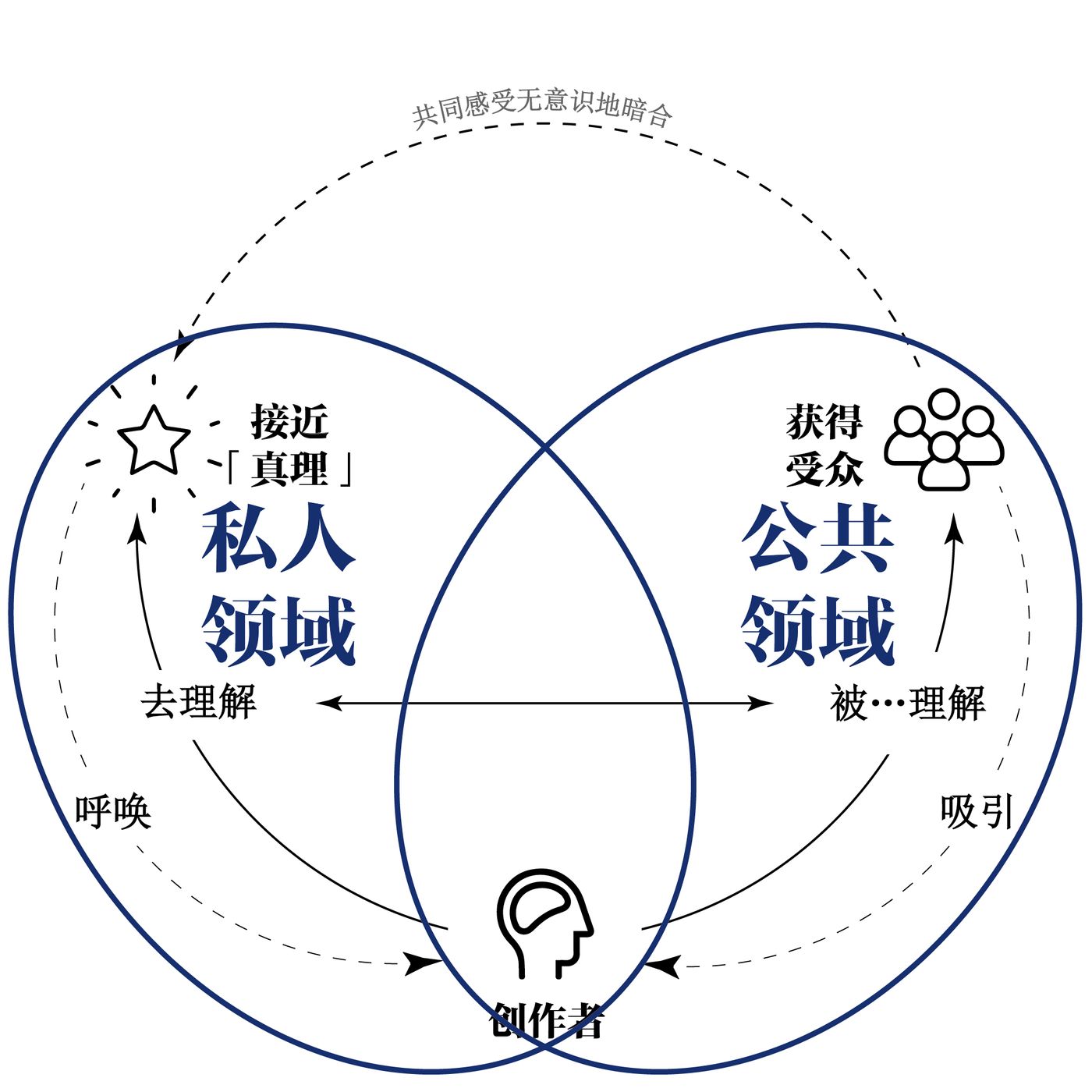

But technological progress has also brought us a set of contradictions. On the one hand, creation is highly prosperous: there is a lot of content and a lot of noise. On the other hand, creation has experienced a deep loss: literature lovers, architects, musicians, and film critics lamented that it is difficult to breed great works in this era. For this point, if we used the necessity of the "public sphere" as an entry point to discuss the demise of discussions on the Chinese Internet, this time we use the necessity of the "private sphere" as a lens to reflect on the loss of creation . The term "creation" as a theme covers not only writing, but also images, music, architecture, video, and more.

01 Digital space, content guided by "Dataism"

First, the space where creation takes place is shifting to online on a massive scale. If in the past a novel had to go through a series of rooms in the physical world, such as a study, a publishing house’s office, a printing room, a bookstore, etc., before it was handed over to readers, now it may take place in the “plane country” of the screen world—perhaps It is a two-dimensional interactive interface such as graphite documents and WeChat public account editors. Even if older or more traditional creators still use paper and pen to create their work, the internet remains a key channel for promotion. It can be said that the Internet space is gradually becoming an important and even main place for "creation" and "publishing".

This digitization process also has structural implications. The interviewer Zongcheng of the Dune Institute (click here to jump) once mentioned this view: "I think today's transition from offline to online is actually an era where readers' power has become more powerful . We can say that a kind of The politics of democracy has spread to the logic of writing . It is more obvious here, for example, in online novels, readers often come to tell the author how to write. If you don’t write like this, you will be handed a knife. …

Therefore, the change of space prompts the binary relationship between creator and audience to change. This change in relationship is also particularly evident in the “rice circle economy”. Now, "fan circles" are no longer satisfied with playing the role of passive recipients. On the contrary, they have strong action and influence on the idols themselves. They uniformly control reviews, public relations, and score points on Weibo and Douban, and they also participate in deciding the next step of idol career planning, becoming paternalistic figures. This is also a manifestation of the audience's "enlargement of power" - the digital space provides the possibility of connection, the connection provides the possibility of organizing the community, and the community provides the possibility of action.

Second, "Dataism" is becoming the guiding ideology of many creations. The process of creators migrating from the physical world to the virtual world is not just an online technical event. The technology of the Internet itself has a strong ideology, such as the respect for data, and this can greatly affect the processes that take place within it. The phenomenon described at the beginning of the article is a clear manifestation.

These data are manifestations of technological progress, making it easier to quantify the value of works created on the Internet, and to display and analyze their economic value.

For example, in the period of web 1.0, the quality of a blog post may be entirely based on the reader's own mind to produce an ambiguous subjective judgment, or the popularity of the article may be inferred from the quantity and quality of comments in the comment area. But in 2021, every article posted on the Internet can generate a huge amount of data, which is itself publicly visible. Through its high and low figures, unquantifiable works have a basis for judgment.

Based on the research of Dutch scholar José Van Dijck, we can simplify the construction logic of social media platform into one sentence: "collect data to obtain profit." The first step, datafication: put the platform Information exchanges, transactions, behaviors, etc. that take place on it become data that can be processed by machines and identified by algorithms. The second step, commodification: transforming the data that can be processed into the currency of the digital age, in which advertisers are an important means of monetization. The third step, automated content selection (automated selection): use the algorithm calculated pattern to create a tailor-made information flow for each platform user that can be “swiped” continuously, increase its stay time, and further collect more information User data.

The deep influence of dataism on creation lies in the fact that data initially served the content and played an auxiliary role in explanation, but gradually the data became the mainstay of the customer, and the content became a vassal of the data. In order to improve the performance of data, many operators are not interested in improving the content quality of their articles, but will look for specialized technical teams to "scan the readings" and "make data"; many self-media and advertising industry workers have also developed Such a habit: After clicking on an article, you basically don’t read the text, but swipe directly to the end to see its reading volume, likes, and “watching” count, as if glancing at these data is equivalent to having read it past the article.

Instagram, the leader in photo-sharing social media, apparently sees this problem too. At the beginning of 2020, they launched a move that surprised many people - hide the user's like count (in some countries). That is to say, "Little A and 89 other people liked it" no longer appears below the photo feed, but only "Little A and others liked it".

Adam Moseley, the platform's director, explained the decision to "hide likes" this way: "We're trying to take the social pressure off of social platforms, making Instagram less of a digital race, and more space for people to focus on. The connection itself – with the people they care about and the things that inspire them.” Susan French, CEO of Social Media Link, commented:

"The future of Instagram lies in real impact, not exaggerated bragging rights."

Of course, Instagram’s business decision is not the opposite of the basic logic of capitalism or dataism. It is a more advanced and milder expression.

It may be because the development of social media ecology is still in different stages, and the performance and visibility of data in the Chinese Internet are still in the stage of continuous increase and increase - the trend we mentioned at the beginning of the article is a good proof: More and more, and more and more visible. Perhaps also influenced by short-term utilitarian thinking, on platforms such as WeChat, Douyin, and Kuaishou, the relationship between data and realization is relatively straightforward. It is hard to imagine which Chinese social media platform will take the lead in hiding the public "read count" and "like count" in recent years. Even the self-media people themselves find it difficult to accept such a move-if the "100,000+" at the end of the article can no longer be seen by everyone, the motivation and sense of value to write will be greatly reduced.

Yuval Harari, in his best-selling book A Brief History of the Future, throws out some thought provoking ideas around “dataism.” Despite his many oversimplified accounts of history and philosophy, this section is still very explanatory for reflecting on Internet creation. In Harari's book, "Dataism" is regarded as a new religion emerging in the 21st century. He believes that adherents of "dataism" believe that "the universe consists of streams of data, and the value of any phenomenon or entity lies in its contribution to the processing of data."

This may seem radical, but in reality many internet users today share a more or less similar belief - that a diary is worthless if it sits in a drawer with dust, or, in other words, it's worth less. In the "unmined" state, the most efficient way to realize its value is to "upload", because only in this way can data such as readings, likes, reposts, comments, etc. be generated.

For dataists, this post-record upload guarantees that the work will feed into the torrent of information, and its value is only revealed when it joins the program.

02 The overall loss of "great works"

The online creation of creative space and the prevalence of dataism have never made the creative process as large, convenient, fast, "equal", and popular as it is now, and it is convenient for statistics, calculation, evaluation, comparison and realization. Dataism is an extension of modernity, emphasizing efficiency, normalization, and growth, and this logic has quickly spread to Internet creation. Interestingly and seemingly unsurprisingly, this "overall prosperity" and "progress" of creation is accompanied by another strong common feeling in this era: the overall loss of "great works".

Angry literature lovers will pronounce the verdict: "Literature is dead." The more moderate will still admit that in this day and age, literature seems to be dispensable. Old-fashioned musicians lamented that there are too few people now to calm down and make music, and everyone is all about the excitement and limelight of the moment. Dissatisfied music critics will sigh like this: "Listen to the top ten popular songs of the year in 20xx, and then listen to what is going on now..." For many veteran movie fans, the torch of the 20th century film masters has not been picked up down. This is not just for places like Italy, Russia, Japan, but a global situation: no success, no successor. From time to time we still see well-crafted, powerful narratives, but where is the soul-stirring stuff like Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, and Tarkovsky? It seems that the new audience and the new director are no longer obsessed with taking the classics of the last century as the white moonlight they pursue in their lifetime.

Technologists feel a sense of optimism , they are forward-looking and see utopias in the future of humanity as dataism brings an unprecedented creative boom. Never in the history of mankind has such a massive and rapid flow of data been produced; humanists feel an endless pessimism , they look backwards and think that the golden age is in the past of human history because they are witnessing true greatness The loss of the work is also saddened by the reality that no one takes over.

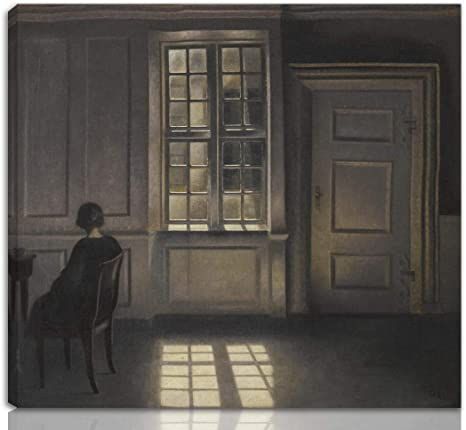

03 The private realm is captured by the screen world

The collective prosperity of creation and the loss of "great works" - two things are related to each other. Dataism advocates connecting, uploading, and interacting anytime, anywhere, so everything should be in a constant, publicly visible spotlight. In this case, the private sphere of the individual is constantly being compressed, and it is constantly being squeezed by the expansion of the Internet. Creators no longer seem to have the luxury of a secluded "dark room." In that quiet and dark place, he could have discussions and conversations with himself alone, pace back and forth in the shadow shaded by the curtains, meditate, smear and wipe on the manuscript paper, and be completely free from being watched and disturbed by the outside world. Today, he doesn't need to step out of the house, he just needs to reach out and pick up the smartphone on the desk, and in an instant, the screen will bring him into that connected world, and the darkness of the private realm will be illuminated by the public light in an instant. .

We have to admit that the process of creating a truly great work must have a good private domain as a premise. In other words, the authoring environment in which the reader's power has grown, and the "democratic" negotiated authoring process we have just described becomes a harmful oppression. Novels, music, images, movies, and podcasts can exist equally in a public domain on the Internet, but if this logic of equality invades the process of creation in the first place, it will cause great harm. That is to say, when creating, the viewer must not be equal to the creator. There is no way for a writer to write while the reader is constantly watching and commenting on the sidelines - a creator-friendly space must allow the work to be privately owned by the creator before it comes out; On the manuscript paper, he wants to be able to have absolute domination over the world he created. If the creator has to accept the presence and direction of the viewer at every moment as he conceives, sketches, or draws a pen, the work becomes sterile, banal, and lacking in courage.

Works always flow between the privacy of creation and the publicity of publication, and the relationship between the two is not a definitive one. The best works we have are in libraries, art galleries, museums, film archives that are open to the public, but the works themselves are not "public". These works have gained a large audience and publicity, but the voice of the work itself is not broadcast to everyone with a loudspeaker.

Regardless of the medium, the best work always seems to speak to a single person. These works condense the creator's thoughts and emotions, and then convey them to readers across time and space, causing a strong resonance. The novels of Kafka and Dostoevsky can sometimes give people an indescribable shock. From the bottom of my heart, I sigh why such works transcend such a long, distant, and foggy time and space, and directly express what they have never said. Hidden, fertile, even morbid pains and impulses are revealed. Such works must first be produced in the dark, and then thrown into the searchlight of the publishing and critical circles; if they remain in the open light, they cannot be completed in the first place.

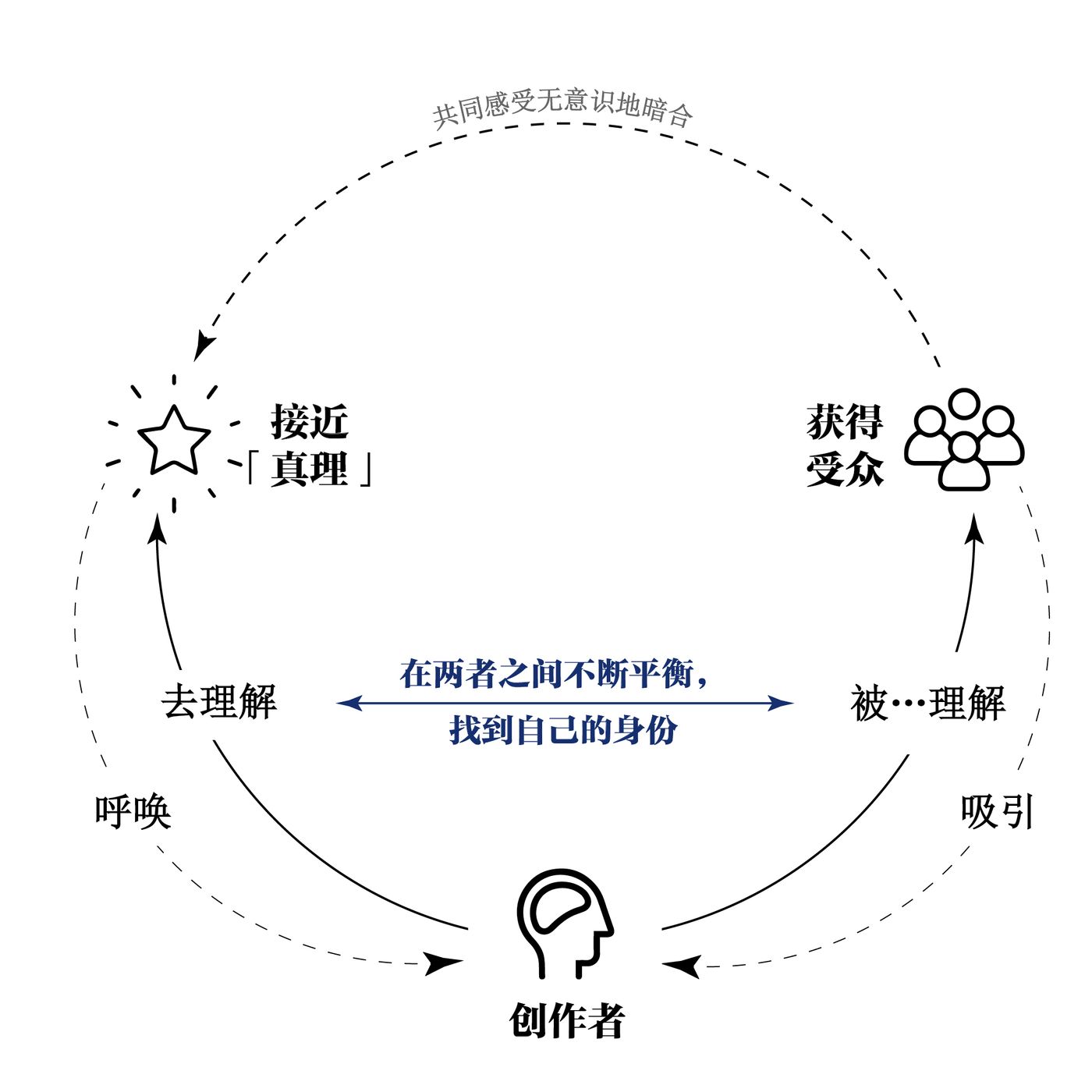

A good work grows from the heart of a private individual, and is finally deeply accepted into the heart of another private individual. In between, they need a public domain as an intermediary to facilitate each other to find each other.

In today's terms, the creator is the "content post", the intermediate agency is the "operation post", private and public - content and operation, the two are clearly demarcated, and each performs its own duties. However, the logic of "self-media" created by dataism makes this boundary ambiguous. At this time, the thinking of operation intrudes into the content in reverse, making many works themselves full of an atmosphere of operation. Internet creation pursues the maximization of "data processing", and the content is no longer attached to human nature and common feelings that can reach the depths of the heart; the latter is diluted by the intermediary between the creator and the audience - the number - .

04 The balance between "understanding" and "understanding" is difficult to maintain

Dataism has a creative destructive power. This is probably why it can be considered a religion. We cannot deny that it has created a lot of new things for the world, but it also suffers from its powerful destructive power: adherents of dataism must strive to elevate it to an overwhelming situation, and drive the "infidels" to extinction. In other words, today's Internet creation is not just an option among multiple creation methods, on the contrary, it is becoming the only one.

The biggest competitor of Douyin App is not Kuaishou, nor WeChat, but the real life of users - the time we study, the time we run, the time we travel... It is conceivable that digital content platforms compete fiercely with each other, but the real The impact is still on traditional content platforms—print media, physical theaters, physical museums, and more. For "dataists", the former can create far more data streams than the latter, and should therefore be seen as a more human direction. At this time, for creators, only by believing in "dataism" and joining it can they achieve themselves, and resistance is meaningless, and will only make the work wander around no one. The creative context under the influence of dataism is becoming the only context. It is conceivable that if there is a Dostoevsky who is still in his growth stage today, he must also face the increasingly urgent and expanding questions of how to communicate with readers and whether to “go online”.

Harari discusses the relationship between "dataism" and classical humanism, emphasizing that the two are not antagonistic. But the mistake in his argument is that he does not realize that "dataism" is essentially an extension of modernity - people's assumed worship of science, rationality and efficiency after the Enlightenment. For the dismantling and criticism of this myth, many great thinkers of the early 20th century have already stood behind us.

Conversation between thinker Hannah Arendt and Quint Gauss shows what this important 20th century thinker thought about creation -

Gauss: …do you want to have a broad impact with these works? Do you believe that, in this day and age, such an effect is no longer possible? Or are these influences just secondary to you?

Arendt: It's not an easy question. But honestly, when I work, I don't care how it affects people. For me, the most important thing is to understand things, and writing is an integral part of the process of understanding things. ...if I have a good memory and can keep all my thoughts, there's a chance I won't write anything down. I understand my laziness. What matters to me is the thought process itself. Whenever I manage to fully think about something, I feel satisfied. It would also satisfy me if I managed to adequately express my thought process in writing. ...as for saying I consider myself influential? No, what I want to do is understand things. If other people understand the world in the same way that I understand it, that will give me a satisfaction, a satisfaction in some kind of equality.

—Hannah Arendt, in a 1964 conversation with Gunter Gaus titled What Remains? (Chinese Translation Dune Research Institute)

This part still continues the previous point of "privacy necessary for creation". The difference between private and public is reflected in both to understand and to be understood - the former activity belongs to the intellectual exercise in our own mind, and the latter activity occurs in creation between the reader and the audience.

We can also use this to understand why creation must take place in the private sphere: the process must be extremely private, involving personal memory and imagination . Publishing, being recognized, and gaining influence are public, but there should be a clear boundary between creation and publication.

On this point of memory, in the dialogue, Arendt claims that the defect of memory is the reason for her creation, but of course, it is also the ability of memory that makes creation possible, just like the ancient Greek Aeschylus (Aeschylus) in his It is written in the play: "Memory is the mother of all wisdom." With the help of memory, invisible thoughts are transformed into tangible and embodied expressions.

As for imagining this, the writing practice of Argentine literary master Jorge Borges must also reflect the necessity of the private sphere. His short story "The Ring of Ruins" might be regarded as a wonderful allegory of the creative process itself. If we understand his protagonist "Dreamer" as a creator, then the creator's greatest effort is to perceive, shape, and play with a vague image imagined in his mind into a specific shape. Most creators feel the same way—the process of creating is to organize the hazy, illusory, and unordered mess of thoughts in the mind into a structured, more sensible material. The same goes for painting, sculpture, and many other creative processes.

In a conversation with a university professor, Borges said: "I only write something when I have to. Once it's published, I try to forget it, and that's easy too." To Borges In other words, writing begins with a feeling akin to a "rush," an accumulation of inspirations, thoughts, images, shapes, and ideas in the mind. When they accumulate to such an extent that they cannot but be poured out, the author "has to" put these abstract concepts into concrete words. In this expression, the author is almost passive, as if he was only summoned by some sublime being—a “God of Creation”—so that creation is a mission that must be accomplished.

Similarly, for Arendt, the most important part of the creative process is the "understanding" part - the creative process helps the creator understand herself better, helps her clarify her thoughts, and let some tangled random thoughts It emerges unmistakably like an island. Many of us have a strong feeling: if you don't understand something, you might as well try to write it down. Through the practice of writing, you will help yourself to understand the original thing. As for being "understood," that is, gaining broad reach among readers and audiences, that seems like an added bonus, or even an added burden, to both of them.

It can be said that both Arendt and Borges advocate a state of "contemplation" - they understand the truth in perfect "alone", and try to reach a higher thing through language in their creation (ancient Greek Philosophers call this higher thing "eternal"). But just as importantly, we should realize that they and their work are not always "alone". We're talking about them right now—their manuscripts didn't just help their own thinking, and have been sitting quietly in a study drawer ever since, but instead, the work was published, understood, and gained a worldwide reputation. So it can be said that the pre-Dataist creative environment allows for the coexistence of these two seemingly opposite intentions—creators write in order to “understand,” and the work ultimately “understands.” Even after they were "understood", they continued to shirk and deny.

*to be continued

In the second half of the article, "Creation in the Internet Age (Part 2)", we will discuss the protection of "dream" in the private sphere, the accommodation of "ideological dirt", as well as the struggle within the work and the inner confrontation of the creator. It will touch on the mutually supportive relationship between the private and public spheres.

(Welcome to follow the WeChat public account "Dune Research Institute", the first-hand content will be updated here. If you are interested in design and architecture study, please follow the WeChat public account "Open Land Laboratory".)

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More