From fighting for freedom to being imprisoned: A female activist's record in a detention center

Every time she was interrogated, Ni Ming (pseudonym) had to walk through the corridor wearing handcuffs and a black cloth hood over her head, with her eyes peeking out from the holes in the hood. In her own words, she was "like a robber in a movie." The hood was made of very hard material and stuck to her neck. She walked forward with her hands, barely able to see the road under her feet.

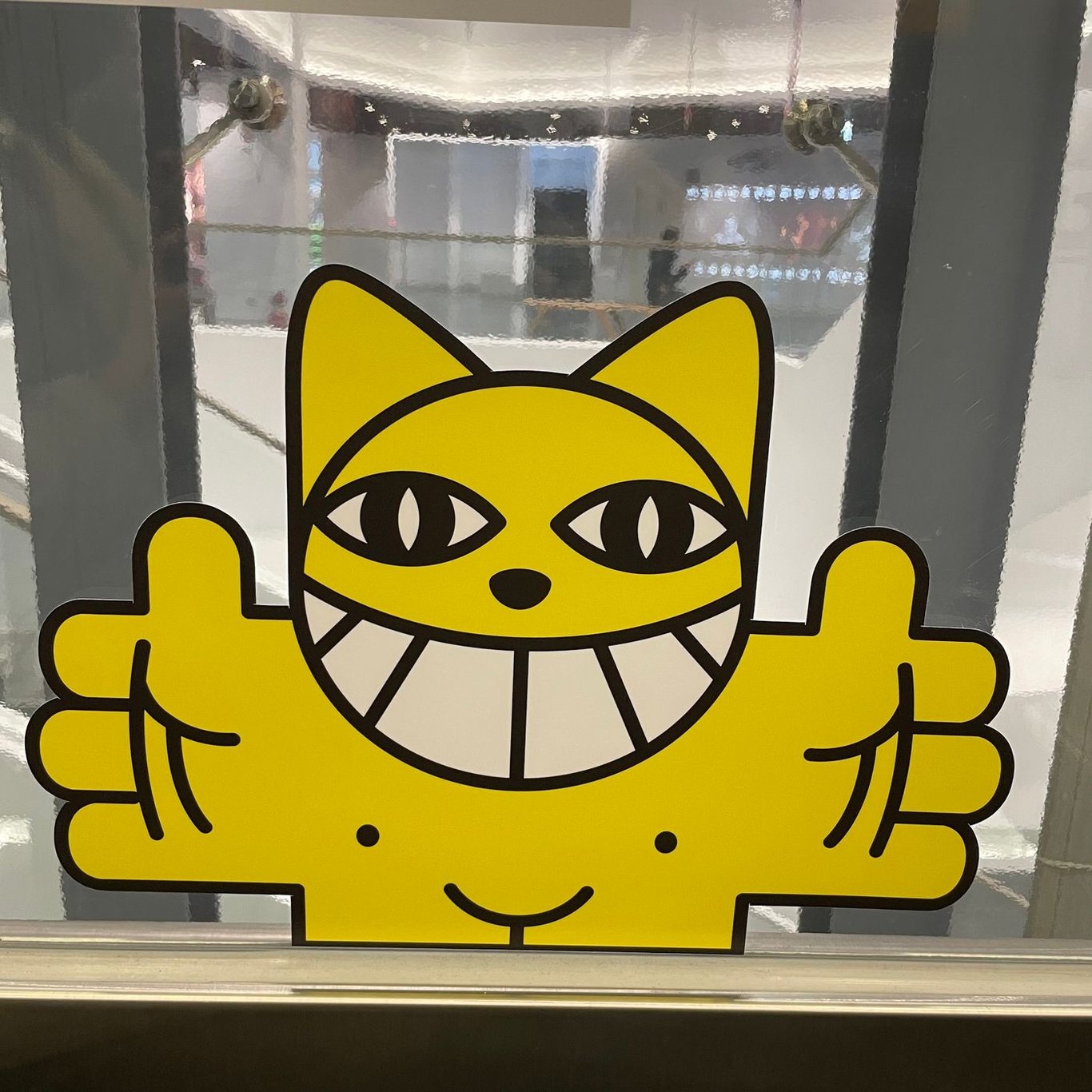

Ni Ming is a "queer feminist" born in Xinjiang. She just graduated from college in 2022 and is active in the field of women's rights and sexual minority actions. In October of the same year, after the "Sitongqiao Protest" in Beijing, Ni Ming printed posters related to the incident and posted them in the women's toilet cubicles of the subway station, and wrote several peaceful protest slogans on the wall with markers. She was immediately arrested on charges of "picking quarrels and provoking trouble" and was detained in the detention center for nearly four months.

After being released on bail in early 2023, Ni Ming created a document to record her life in the detention center, but she was reluctant to start because "my mind and actions were very resistant." She thought this might be a self-protection mechanism: "You have to force open those emotions and memories that you suppress unconsciously... As soon as you hear the key words, those (negative) things will suddenly surge up."

Now, in her daily conversations with friends, she can naturally treat the stories of her detention as jokes. But the painful memories still flash back from time to time, and because of this, she feels that "I feel I need to really face some things." This urges her to express herself publicly, sort out and speak out her experiences and feelings at that time.

“I want everyone to live with dignity”

On October 13, 2022, the day of the "Sitong Bridge Incident", Ni Ming turned on her phone after get off work and saw many friends saying that they cried. She missed most of the discussions on the Internet, and barely pieced together the incident from a piece of "deleted", digesting the information silently by herself.

At that time, Ni Ming was doing community service work in a remote village on the outskirts of the city. Around the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the government once again emphasized that "the dynamic zero-clearing policy is sustainable and must be adhered to", and the social control brought about by epidemic prevention has increased. The activities that Ni Ming had prepared for a long time at her workplace were asked to be suspended on the grounds that it was a "special period". In her opinion, local migrant workers are mainly engaged in the service and construction industries. They are in a particularly vulnerable position under the unequal policy environment and economic shocks, and their lives and families are "more affected by excessive epidemic prevention policies."

But at the same time, compared to campus or central cities, protests are rarely mentioned here because people lack the resources and channels to learn about relevant information. There is a gap between the situations and reactions of the people around him and Ni Ming's cognition and feelings.

A few days later, Ni Ming learned that some universities began to prohibit students from printing paper products on campus. It may be that some students responded to the protest, and the school used this to restrict students' words and deeds. All this made her feel absurd and "see no hope." She had been taking medication for bipolar disorder for a long time, and political depression and emotional problems brought her a double dilemma. She urgently needed to "go to the real physical space" to "talk" with others - "If there is no concrete action, my life will not go on."

In late October, on a "chilly autumn day", Ni Ming was in a particularly low mood due to the weather. On that day, she made up her mind to post posters at the subway station near Chengbian Village. On the posters and the wall next to them, she wrote slogans: "We saw it", "Peaceful protest, no more silence", "No lies, but dignity, no nucleic acid test, but food, no lockdown, but freedom"...

She had not thought about how much of a response her action would have, "Maybe the next person who enters the cubicle will just take it off or call the police." Although she was mentally prepared for the consequences of being discovered, the possibility that "someone saw it and resonated with it" was more important to her.

Nothing happened the next day, so Ni Ming printed new posters and put them at home. In the middle of the night, she was awakened by a noise and opened the door to see "a sea of black": a dozen police officers stood outside the door, and her roommate was trying to stop them. The police rushed into Ni Ming's bedroom under the pretext of conducting an epidemic survey, saw the flyer, and said, "Don't look for her, it's her."

Later she learned that the police had investigated based on the surveillance footage outside the public toilet for a day and a night, checking everyone who entered and left during the time of the incident, and finally locked in on her.

Ni Ming's room was searched. The police repeatedly questioned her with receipts from overseas websites, saying, "I think there must be foreign forces sending me money." One of the police saw the books and brochures in the room and asked her if she was a feminist. Ni Ming subconsciously answered "yes", but later regretted it a little, saying, "I don't know what his definition of a feminist is."

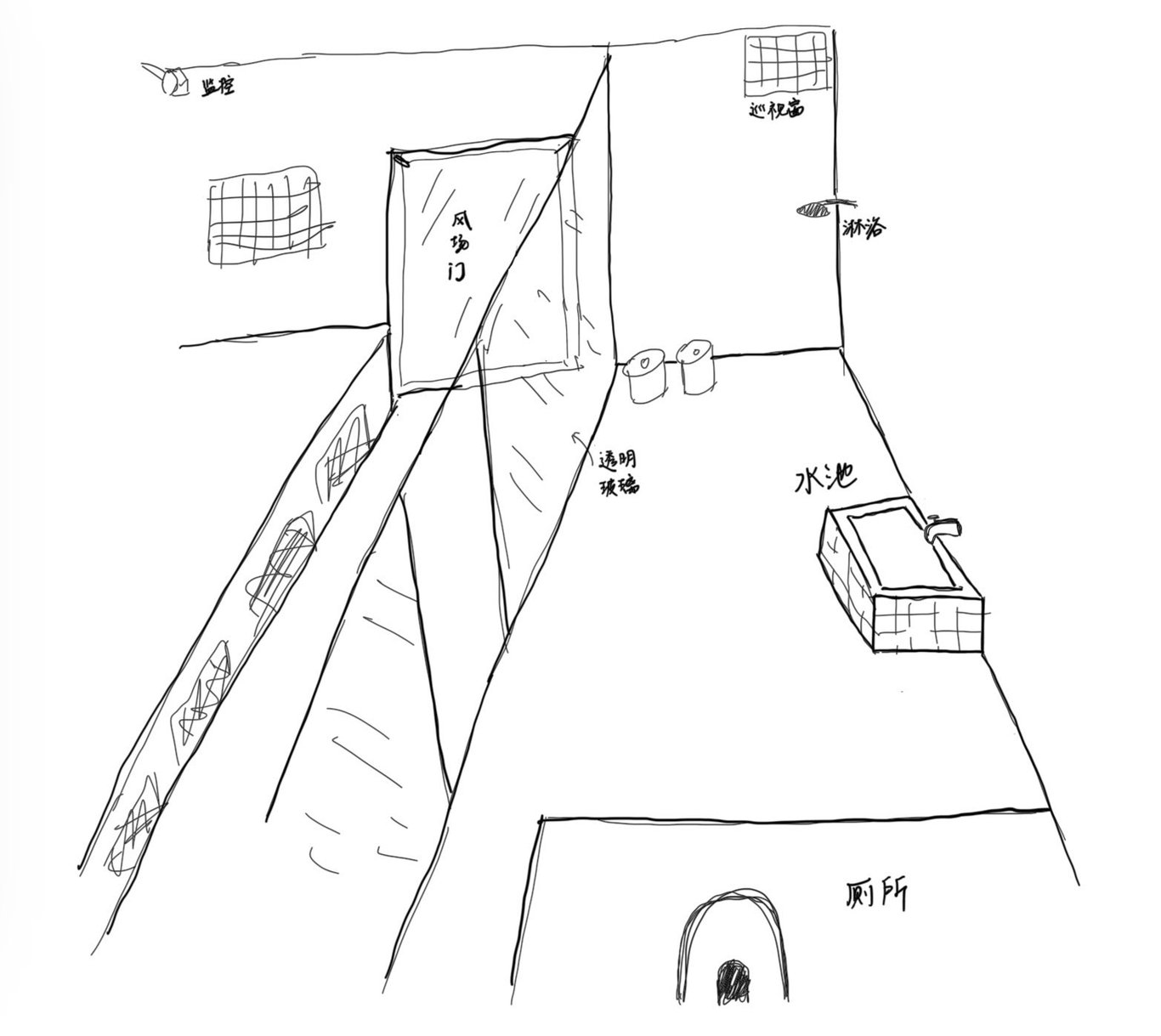

Perhaps because she was a young woman, the police were more polite. But she could not move freely at home and had to leave the door open when she went to the toilet, with a female police officer guarding outside. This made her realize for the first time that her rights were being deprived. From then on, until she was detained and released on bail, she never had the chance to have private space again.

In the early morning, Ni Ming was taken to the police station and sat on an iron chair in the interrogation room. Police officers from different departments took turns interrogating her and asked her to explain the purpose of posting the slogans.

At first, she talked to the police "completely in her own way". The other party asked her, as a person with higher education, why "she didn't go to work and do these things", Ni Ming replied, because "I want everyone to live with dignity". She realized that perhaps because it was a tacit consensus, she and her friends had almost never had such exchanges, and the questions raised by the police at that time prompted her to think about the "deeper motivation" of her actions.

She described the impact of her upbringing as sincerely as possible, from the control of the Internet and speech she felt after the "July 5th Incident" in Xinjiang to her marginalized experience as a minority, woman, and sexual minority. But the police seemed not to understand and thought she was deliberately using complicated language to "confuse them." Ni Ming felt that the police had prepared a narrative and just wanted to get more details from her to support it: they were concerned about how she obtained VPN and overseas information, and whether she was "organized and premeditated" and "intended to split the country."

The interrogation lasted 24 hours. During the interrogation, Ni Ming was so tired that she fell asleep in her chair. The police asked her to "hold on a little longer." When she learned that she was going to be transferred to the detention center, her "heart sank" because she really didn't expect that just "posting some posters and writing some slogans" would have such serious consequences. But the police told her that she could rest once she got there, so she was even a little impatient. "Later, I realized that they had deceived me."

On the day she was sent to the detention center, she had originally planned to go to the psychiatric department for a follow-up consultation. As the doctor's shift was about to end and the interrogation was not over, the police claimed that they could "call the doctor over" in order to appease her. However, when she was finally taken to the hospital and went through the prescribed epidemic prevention procedures, the doctor she had scheduled had already left.

Sitting in the waiting area, Ni Ming's tears flowed out with her suppressed emotions. This was her first breakdown since her arrest. The last bit of her trust in the police disappeared: "They think they are very privileged and don't care about other rules at all."

Loss of freedom

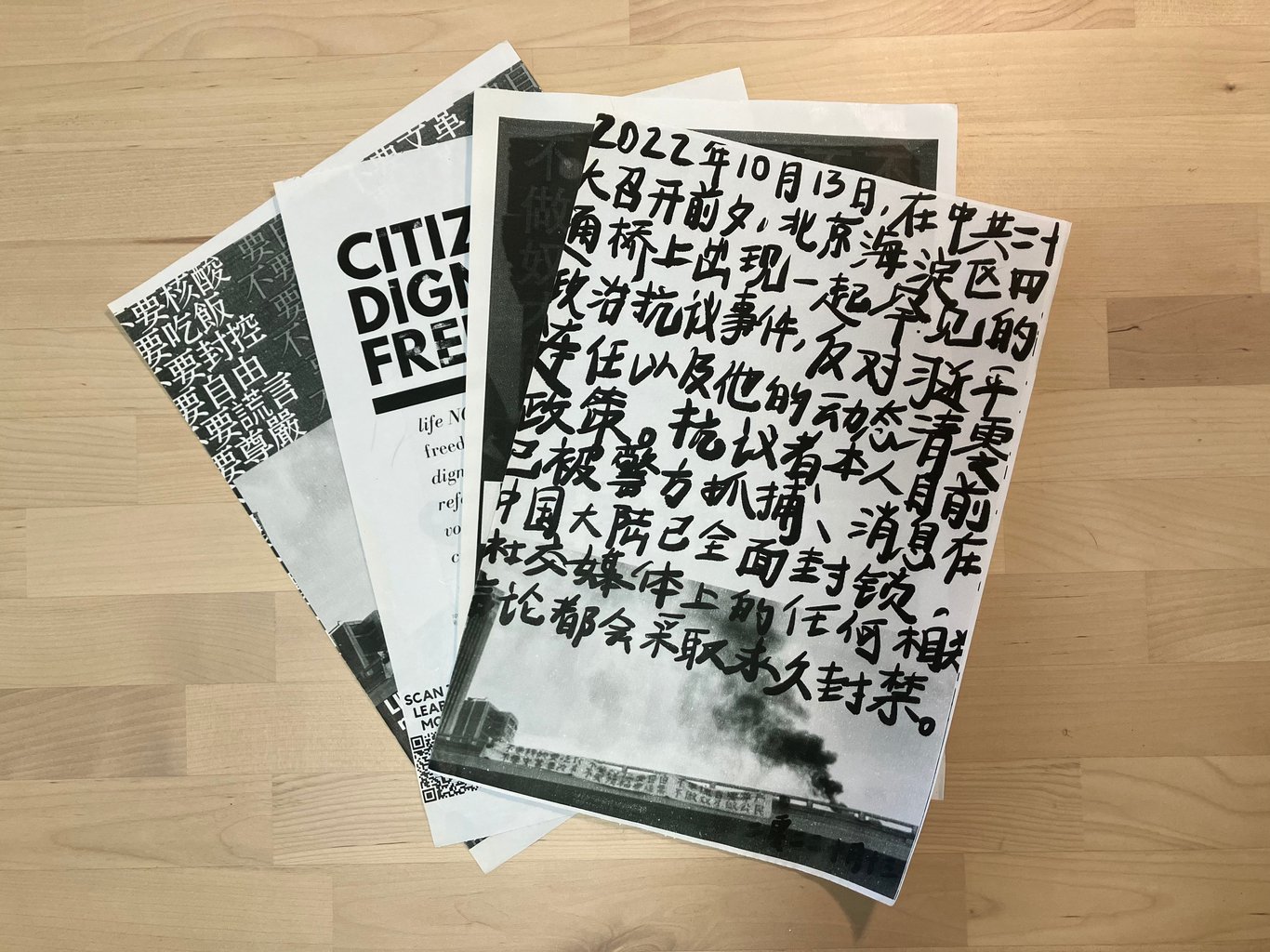

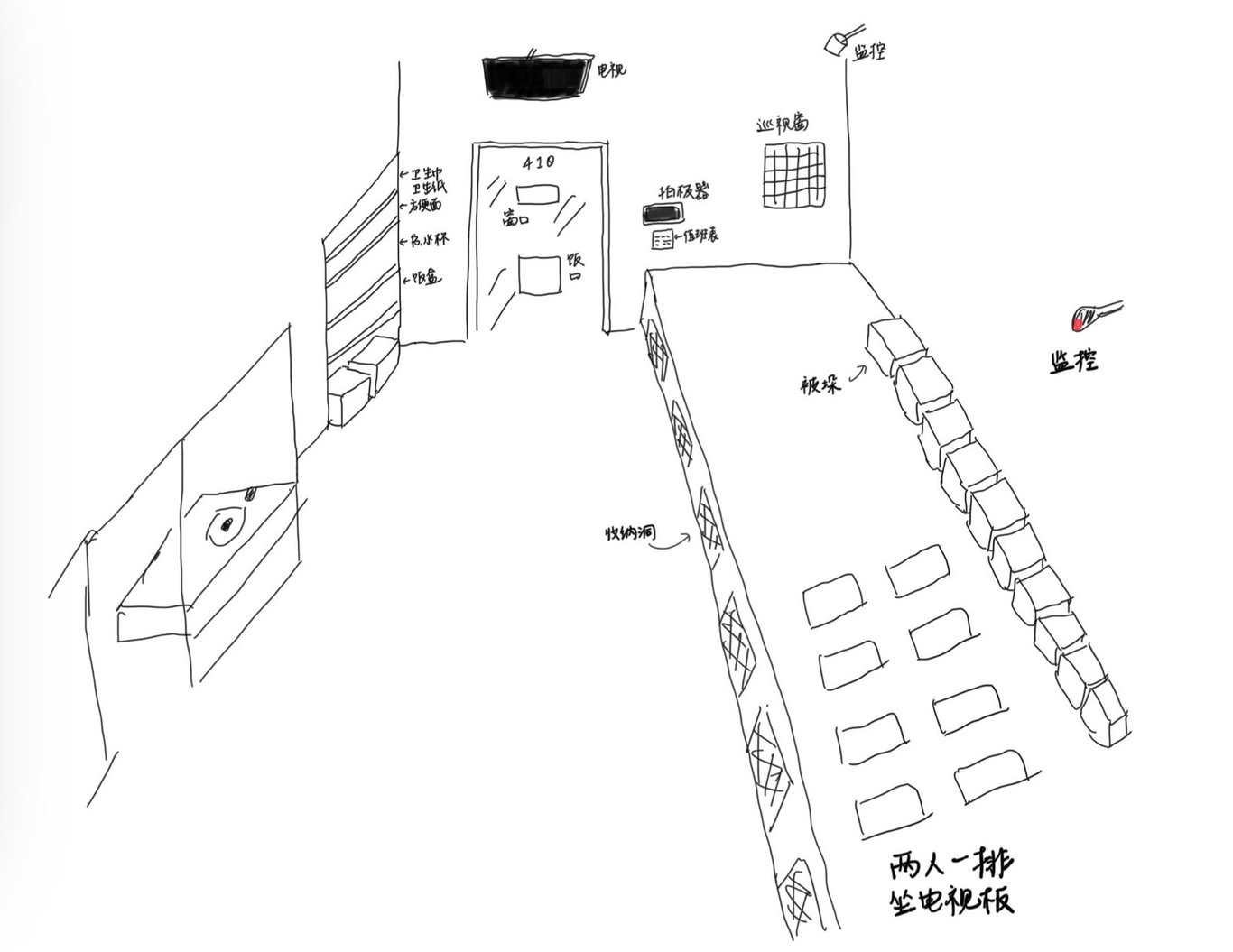

The cell where Ni Ming was detained was about 30 square meters and held 14 people. A bed board slightly higher than the bed occupied two-thirds of the entire cell, and the remaining space could accommodate at most one person to walk back and forth. She spent most of the day on the designated bed, and the space for sitting and lying was "just that one spot", and she also squatted on the bed board to eat.

Ni Ming, who had just arrived at the detention center, was a "troublemaker". On the first day, she had an argument with the "head guard (note: the detainee in charge of other people in the cell)" because she wanted to sit on the floor to eat: "I've read the prison rules, and there's nothing that says you can't sit down to eat." The head guard said no, and told her that even if she was a "sixty or seventy-year-old lady" with poor health, she still had to squat to eat. The quarrel attracted the attention of the cell guard who was somewhere unknown. The voice came from the loudspeaker, reminding Ni Ming to pay attention to discipline, "Not all the rules in the detention center are written down." Ni Ming squatted down and finished her meal crying.

The prisoners strictly follow the time schedule every day, and in order to compete for the title of "civilized cell", each cell has its own set of rules. Before 6:30 in the morning, the on-duty personnel will wake everyone up one by one, and everyone will lie on the bed and "squirm" to put on clothes and fold quilts. When the guard rings the bell, they will immediately get up and line up to go to the bathroom to wash.

Ni Ming needs to take medicine every morning, but the time for dispensing medicine is not fixed, so she needs to be ready at all times. Sometimes when she is brushing her teeth, the doctor comes, and she has to spit out the toothpaste in her mouth and go to get the medicine. There is also a strict process for taking medicine: hold the water cup in one hand, take the medicine with the other hand and put it in your mouth, swallow it, open your mouth for the supervisor to check, and stretch your hand to prove that you did not hide the medicine, and finally turn left and walk back to your seat. She was blamed more than once for not stretching her hand or turning the wrong direction.

After breakfast, the voices of people reciting prison rules could be heard from different cells. Sometimes the recitation material would be changed to "Standards for Being a Good Pupil" or "The Maxims of Zhu Xi on Managing a Family". Ni Ming said, "I didn't recite them anyway." During this time, the prison guards would arrange for someone to fetch water for everyone in the cell - including drinking water and domestic water. They only had time to fetch water twice a day.

In the morning, everyone stayed on their bunks and usually queued up to go to the toilet. Ni Ming was the last to enter the detention center, and was ranked last in terms of seniority: "Life in the detention center is a great challenge to my bladder."

At 9 o'clock, the prison rules began to be broadcast on TV, educating them to "admit their crimes and accept punishment as soon as possible." Around 10 o'clock was the time for exercise, which lasted from ten to twenty minutes, "depending on the mood of the guards." Everyone lazily did a set of radio gymnastics, and then the iron door of the cell was opened, and they went out to "walk in circles" while the guards patrolled back and forth on the second floor.

The detainees were allowed to take a shower once a week and wash their hair twice a week, each time for 7 to 11 minutes, with someone counting down beside them, "7 minutes, 6 minutes, 5 minutes, 30 seconds, 20 seconds..." Every evening at 6:40, they sat on the planks waiting for the 7 o'clock news broadcast, and everyone had to watch the whole thing. Before 10 o'clock, everyone lined up to go to the toilet again, and the day was over.

According to formal procedures, the maximum period of criminal detention is 37 days, after which the procuratorate decides whether to approve the arrest. However, on the day Ni Ming entered the detention center, she received a notice to "stop calculating the detention period" on the grounds that she had a history of bipolar disorder and the judicial department wanted to conduct a psychiatric evaluation on her. The doctor could not enter the detention center because of the health code pop-up window, resulting in her detention being indefinitely delayed.

In addition, the detention center also conducted an internal consultation with Ni Ming, the main purpose of which was to determine whether she had "suicidal tendencies" and "whether she would threaten the safety of others." Ni Ming told the doctor that her "condition was very stable and she had been taking medication on time," but she was still subject to targeted control as a "major risk person":

She had to wear a red identification uniform. In addition to the guards, there were four other inmates in the same cell who took turns watching over her. There had to be one person within one meter of her at all times. If they "failed to keep an eye on" her, they would be scolded, and even the entire cell could be punished. Therefore, during busy times, everyone's temper was not very good. Ni Ming had to report to the toilet, and she was not allowed to move her body much during breaks. Once, she wanted to put her hands on the wall to press her back, but was stopped by the headboard, "probably because my back was facing the surveillance camera."

She felt she was trapped in a distorted system and longed for something "out of reach": "I can't blame the people around me because they are also wronged. But I can't find a space for negotiation." At first, after getting up every day, she would say to herself, "Another ridiculous day is about to begin", and soon, she just spent every day "mechanically".

In mid-November, Ni Ming received a second consultation. The doctor appeared remotely on the TV screen, while she was locked in an iron chair and handcuffed. She described herself as "tearful" when she spoke. The doctor asked her how she felt when she recalled her original behavior. Ni Ming said that she had written "freedom" on the slogan, hoping not to be forced to be isolated and not subject to speech control. "I am sitting here now, and you asked me to think about freedom. I think it is too ironic."

Sex education in prison

Occasionally, Ni Ming would receive letters from her friends, which was a chance for her to "replenish her energy." Although these letters were only sent to her after being reviewed, she would immediately tear them up in front of the guards and throw them into the trash can after reading them. Sometimes she would cry while reading, and the guards would stop her rudely. On the way back to the cell from the disciplinary room, she kept recalling the contents of the letters, and even repeated them in her mind while lying on the board for a nap, trying to prolong the happiness brought by the words. "Overall, these moments are still very scarce."

At the end of November, a large-scale epidemic broke out in the city where Ni Ming was located. The government said that the local area was facing "the most complex and severe epidemic prevention situation since the COVID-19 outbreak." The detention center immediately entered a strict lockdown, almost cutting off all contact with the outside world. At that time, Ni Ming had a "deep sense of loneliness and despair": "If the end of the world is coming, and I have to stay with this group of people, then I might as well die."

Ni Ming, 25, is the youngest in the cell and calls others "sister" and "auntie". Most of the people except her are economic offenders, "everyone feels that they are wronged". Ni Ming said: "I am the only one in the cell who really feels that I have done something to be sent to the detention center". Because of the epidemic, many people's cases have not progressed, and the cell is filled with resentment. Everyone "keeps cursing the public security, procuratorate and courts" and is very rude to each other.

Ni Ming and others don't have much in common. On Saturdays and Sundays, everyone gets together to play cards, but she usually stays alone to read books or watch TV. She is cheerful and active outside and has many friends, but here her cellmates describe her as "not very talkative." Ni Ming also realizes that the lack of communication has made her living space even more cramped, but she "is not that curious" about these cellmates and finds it difficult to understand each other.

This situation continued until New Year's Day, when the headmaster required everyone to perform a program at the gala. Ni Ming didn't want to sing or dance, so "facing a room full of women," she decided to perform a scene from the feminist drama The Way of the Vagina, "In the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department," about an obstetrician and gynecologist telling the stories of abortion, gynecological diseases, and sexual shame experienced by three generations of women.

She reviewed the lines in her mind several times. After the performance, the sisters showed more interest than she expected, praising her for her "versatility" and saying that they resonated with some of the stories and that they "wanted to convey some of the content to their children" in the future. Ni Ming was very happy. She had never talked about "things she really cared about" here before. This was the first time she showed the real side of her daily life. She realized that she still had the ability to speak: "I was not completely defeated."

On January 12, 2023, the first snow of winter fell, and a sister who was out for a court hearing brought back the news. The sky is almost invisible in the detention center, and everyone rarely has the opportunity to check the weather forecast, but they are extremely concerned about the weather changes outside. In the uncertain waiting, they rely on the solar terms and "Nine Days" to measure the "day scale".

With the implementation of the "Class B and Class B" policy and the shift in epidemic policy, Ni Ming's time in the detention center began to flow again. In early February, she "looked forward to it for a long time" and finally received the mental evaluation report and the notice of "recalculating the detention period", which meant that she could at least have some expectations for the future and had the opportunity to be released on bail pending trial.

However, by this time Ni Ming had already "got used to erasing overly optimistic thoughts" and told himself to "focus on the current life in the detention center" and to "show his skills" and do more things in there.

On February 8, the news of her release on bail came faster than expected. She still queued up with others to wash, do laundry, and watch the news as usual, always feeling that "nothing comes true until the last second."

The sisters and aunts in the cell were happier than she was, singing "Wish You Peace" and "Tomorrow Will Be Better" for her, and each of them said a few words of blessing. Some asked for her lunch box and slippers, hoping to get a good luck, and some asked her to pass on a message to relatives and friends outside.

Ni Ming has a very "luxurious" small purse, which was sewn by an aunt using toothbrush bristles as needles, thread from cotton-padded clothes, bed sheets and elastic bands of masks, and various prohibited items and "unparalleled creativity". But this little gift, which she had just received a few days ago and cherished very much, could not be taken with her when she left, and it had to be left in the cell along with her memories.

Around 8 p.m., Ni Ming was taken out of the cell by the guards. Someone behind her shouted at her, "Go forward, don't look back," but she turned around and waved. She was a little uncomfortable realizing that she didn't have to wear handcuffs. When she walked out of the cell, she subconsciously squatted down as she usually did when being interrogated, but then she immediately reacted and stood up straight.

Afterwards, "just like in a TV drama," she stood at the gate of the detention center and watched the door slowly open.

Meeting friends in the spring

That night, Ni Ming met her friend who had bailed her out at the police station, and the two of them hugged each other, crying bitterly. Her friend looked at her and said, "Why are you so thin?"

The next morning, Ni Ming woke up very early because of the habit she had in the detention center. She went out and walked on the street. The snow fell on her body, bringing a sense of solid weight. She thought to herself that she was really "outside the detention center" now.

She seemed to be "airdropped" into this open city, and everything was turned upside down. One day, she saw the "leftover health code from the previous period" in a taxi, and she felt a little dazed for a moment. Only then did she truly feel the changes in the outside world: some things that "really existed" were silently erased.

Soon she got used to a life without wearing a mask or scanning a QR code to register her identity information. But the body's memory is not so easy to erase: because of amenorrhea and insomnia, she took medication for a period of time; sometimes when she turned over in bed, the memories of the detention center suddenly flashed back, as if she was still in that small space on the bed.

In the first month after being released on bail, she kept moving from place to place. At first, she lived in a friend's house, and two plainclothes officers were guarding the door 24 hours a day. Whenever she went out, they followed her, "making no secret of following her." Later, she moved to a short-term rental house, and the police from the local police station came to register her information every few days. When she moved for the third time, the police went directly to the landlord to terminate the contract. She learned from the police that "the entire district would not accept my materials." Ni Ming was not unprepared, but the repeated negotiations and disputes gave her a headache: "You will find that they are really unreasonable."

At first, she received messages of condolences from friends on social media, but she didn’t dare to reply due to risk considerations. On the other hand, “from the Sitong Bridge protest to the White Paper (movement), I don’t know how many things happened, and most of them were probably silent.” She gradually learned that some of her friends had also been imprisoned, and some had not even been released yet.

She felt an inexplicable sense of guilt about this, "I am safe now, but there are still many people who are suffering misfortunes."

Gradually, she realized that even if she or other arrested people received support, "those narratives" were completed by friends or the media, and everyone was unable to speak for themselves. So she decided to stop self-censorship and "tell everyone what happened in my own words."

In late February, on her 26th birthday, Ni Ming posted her first post on WeChat Moments: "I didn't have time to say goodbye in the early hours of October, and walked into an absurd and closed space. More than 100 news broadcasts became a mirror of the real world. With the arrival of spring, I finally have the opportunity to read letters from friends..." The picture was a photo of her organizing community activities in the past: the sun was bright, and she was standing on the lawn. Her friends left rows of tearful and hugging emojis below. Someone said to her: "Happy birthday, long live freedom."

In the following year, Ni Ming was summoned every month to take statements and "sign and seal".

She is always surrounded by anxiety "derived from public power". Sometimes when she walks on the street and sees a man "dressed in black, wearing a hat and a mask", she will subconsciously suspect that she is being followed. She will also feel panic for a moment when she receives a call from an unfamiliar number. But she is also trying to recuperate and regulate her emotions: on social platforms, she introduces herself as a "freelancer" whose job is "dyeing friends' hair and massaging friends' cats"; every time she goes to the police station, she has to "show the police a new hair color".

At the end of November, the first anniversary of the White Paper Movement, she saw that the streets where crowds once gathered were "like being decorated with red and blue neon lights", but in fact, the lights of police cars were flashing day and night. She guessed that if it were "an old man fishing or an ordinary citizen jogging in the morning", they would probably turn a blind eye to this scene, or even feel safer, but she could only feel anger and fear, and her heart rate would rise just by passing by.

In April 2024, Ni Ming, who was released on bail pending trial, made a decision: to leave. She applied for a program to study abroad and bought herself a plane ticket to go abroad. Although the future is full of uncertainty, her clearest idea at the moment is to end the vulnerable state she is facing first.

Although both the Sitong Bridge protest and the white paper protest were described as having a crucial impact on policy changes, Ni Ming's feeling about the original poster-posting action was that "when it comes to individuals, everyone still feels that they really didn't do anything." Looking back on it all, "the punishment we received, the consequences we suffered, and the responsibilities we shouldered were disproportionate to our initial actions."

Therefore, even if she knew what would happen to her later, she would still make the same choice, except that her goal would no longer be to "create a little echo in private spaces", but to do it in a more public and, in her opinion, more meaningful way: "I will do it in a bigger way."

Author: Lu Shengsheng

Edit: Hezi

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!