Why can't you see beggars on the streets of Japan?

Having lived in Japan for nearly 20 years, I have never seen a Japanese beggar until now, but from time to time I can see ragged vagabonds or homeless people lying under bridge piers, underground passages, parks, etc. return person.

For native Chinese speakers, they can roughly understand the difference between beggars and homeless people. I think the main difference is whether they will actively beg people for money or food. However, the Japanese seem to be indistinguishable, especially those born after the Heisei era (around 35 years old). Maybe it's because they've never seen a real beggar in their lives.

In Japanese, there is [begging food] (こじき) which means beggar in Chinese, and the English loanword [ホームレス] (homelessness) refers to the homeless (commonly known in Taiwan, homeless), and many Japanese cannot distinguish between these two words. the difference. Some people think that new beggars are called homeless, and some even think that it is only the difference between Japanese and English.

It is not that there are no beggars in Japan, nor is it mentioned by other media. The Japanese are not called beggars because they do not want to beg out of self-esteem. (Of course, there must be some people who really don't want to beg from others.) Japan's constitution and laws expressly prohibit begging from others. Article 25 of the Japanese Constitution states that all citizens have the right to live a healthy life at a minimum. The state must strive to maintain the level of social well-being, social security, and public health necessary to improve life. Accordingly, relevant laws such as the Living Protection Act, the National Pension Act, and the Minimum Wage Act were enacted. The laws related to begging can be found in Article 1, Item 22 of the Minor Offences Act promulgated in 1948, which expressly prohibits begging, or causes others to beg, and violators will be detained or fined. When someone reports begging, the police must accept it. Over time, the profession of beggar disappears.

The provisions of the "Minor Crime Law" are quite clear and detailed. More than 30 legal provisions use quite a few Chinese characters. Even if you don't understand Japanese, you can infer the meaning to some extent. If you are interested, you can visit the following website of the Japanese government.

https://elaws.e-gov.go.jp/document?lawid=323AC0000000039

Item 4 looks like it's specifically for the NEET . In September 2012, the Nara Prefectural Police arrested the suspect on the grounds of violating item 4, "Having the ability to work but not taking up a job, without a fixed residence, and wandering the streets." In a follow-up report, the male suspect was said to have been detained, but was not charged by prosecutors and was eventually released.

Although there are no beggars in Japan today, humble cardboard boxes or blue canvas huts can be found in secluded parts of parks, in which homeless people live. The existence of these people is not a decent thing for the Japanese government. Therefore, occasionally in special periods, public power is mobilized to forcefully disperse the homeless and drive them out of the gathering place, and sometimes there will be individual bullying of the homeless. event occurs.

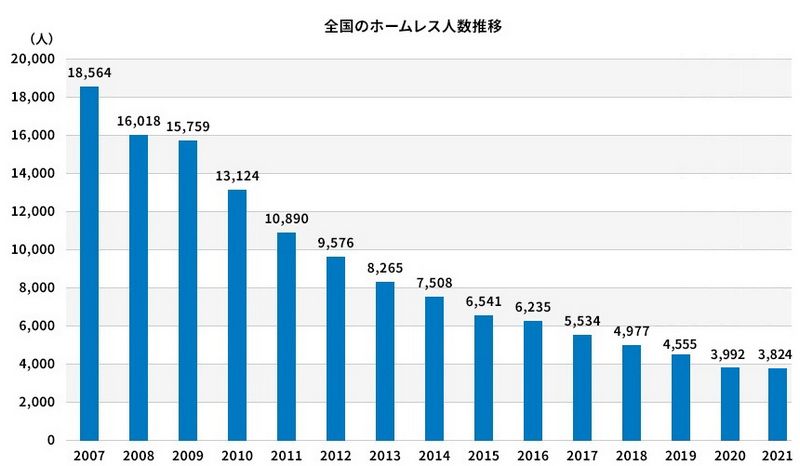

The Japanese government does not completely adopt deportation measures. In order to take care of the homeless, it established the Special Measures Law for Homeless Self-Reliance Support in 2002 to assist them in employment, housing, medical care and other issues. According to statistics from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, there were 25,296 homeless people in Japan in 2003, with an average age of 55.9 years, and 39.8% of them were working full-time in their last job. Subsequent statistics appear to be decreasing year by year, with only 3,824 last year (2021). However, I personally doubt the correctness of these numbers. In Japan, it is very important to have a fixed domicile (address), and many transactions require a fixed address to handle. Since these people have given up their residence, they are also giving up their application for life protection from the government. Of course, it is not easy to apply for life protection in Japan, which is more difficult than in Western countries such as Europe and the United States, which is one of the reasons why they give up the application.

Homeless people can't (unwilling) to beg, and most people choose to pick up and recycle resources to earn a meager income, or rely on restaurants, supermarkets, and convenience stores to prepare discarded food to survive. Social welfare groups or individuals will also provide lunch boxes and various daily necessities from time to time, so it should be safe to maintain life.

In addition, I don’t know if anyone has ever seen a monk standing quietly in a corner of a Japanese street to ask for alms, although his behavior is similar to begging (it’s not accurate to say that, “begging” was originally a Buddhist term, but it was later commonly used in Begging, that is, the later meaning is transformed into "beggar". Taiwanese and Japanese are very good, and "begging" is also regarded as "beggar".) However, monks will not be banned by the police, because this belongs to Buddhist practice an act.

Incidentally, the word [begging for food] is one of the [discriminatory terms] (Chinese: discriminatory language) in "present-day" Japan, and is no longer used by public media such as newspapers. Now most of them use [ホームレス] instead of [Begging for Food], [Begging for Things], and [Floating Waves].

2022/03/30 posted.

Original link to Japan behind-the-scenes observation

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More