Russia-Ukraine Historical Relations and Imperial Trauma

Hello everyone! It is a pleasure to come here and discuss issues with experienced seniors and everyone.

Russia is obviously a country that many people are concerned about. Its influence in China does not match its current national strength. Now that Russia is in the middle of a war in Ukraine, many people (Chinese plus foreigners) see this war as a very iconic event, representing a turning point of an era. Why is Putin starting this war? What will the direction of this war look like? It's a question that many people care about.

A recent study I did has a lot to do with the history of the Russian Empire. While doing this research, I found that some parts of my research output may help to answer these questions. Here, I will share my research results with you, hoping to get your criticism and correction.

one

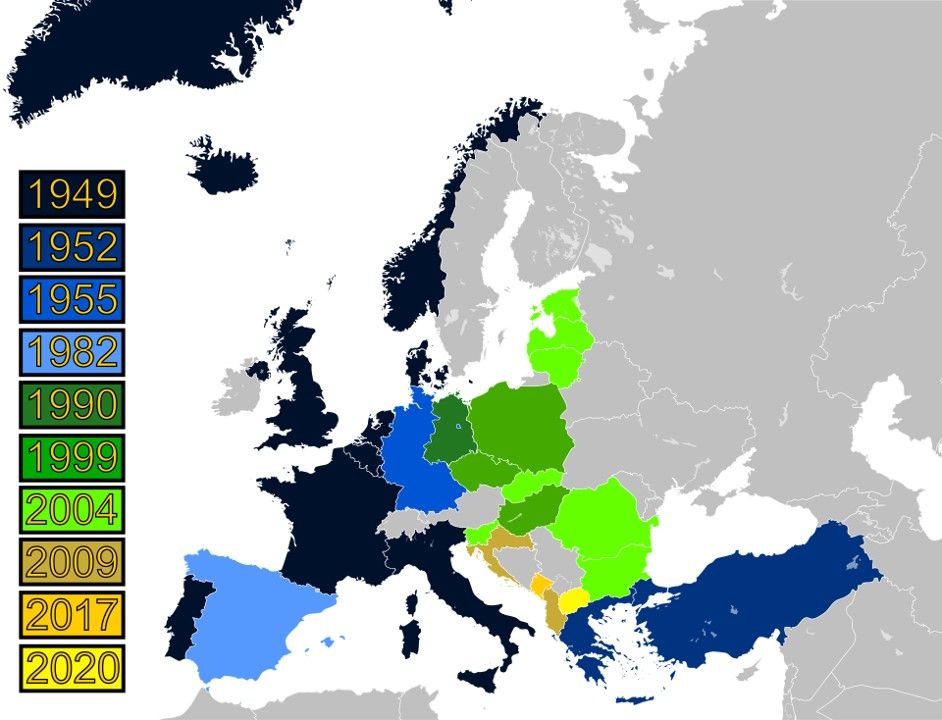

Why is Russia launching a war against Ukraine? Many people think that it is to deal with NATO's eastward expansion and establish a safe zone (including some Westerners also think so)-but in fact, this does not make sense, because Russia's western border (not counting the enclave of Kaliningrad) There are four countries in total, Estonia, Latvia, Belarus and Ukraine. Among them, Estonia and Latvia have already joined NATO, and their borders with Russia are not short. They have the greatest hatred for Russia, and they are also facing the elite areas of Russia. Logically speaking, they are the biggest threat. Obviously, if Ukraine's entry into NATO poses a threat to Russia and prompts Russia to use force, then this threat must not be military.

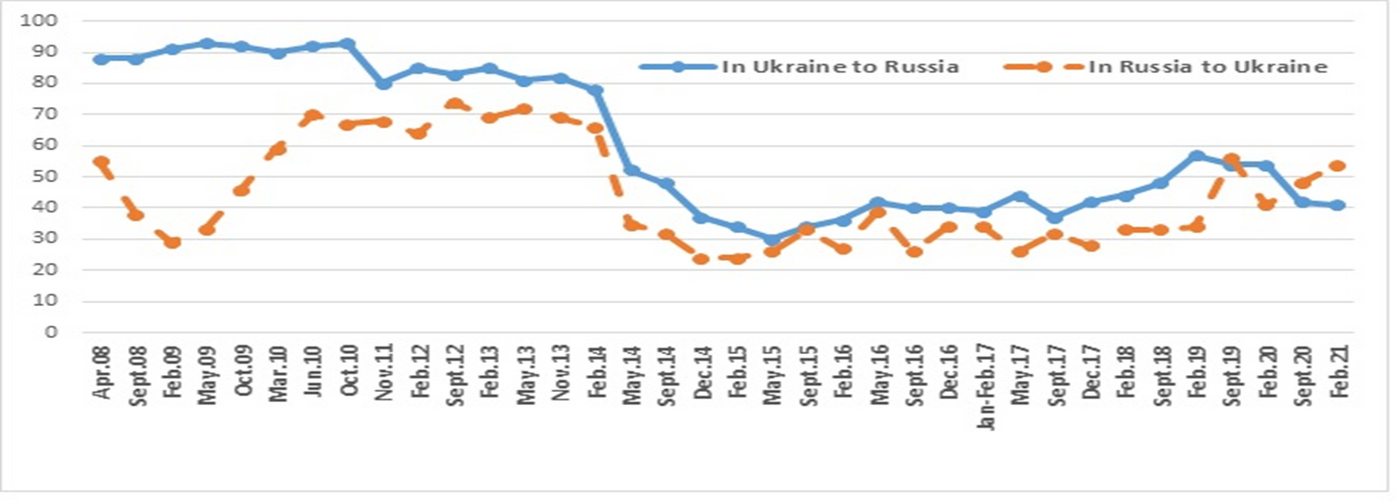

Others believe that this is to send troops to save the Russian residents in eastern Ukraine. But as independent polls have shown, Ukrainians have had a very positive view of Russia in the past until Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014. But even in February 2021, Ukrainians are still equally divided between friendly and anti-Russian. [1] But even so, the political contradictions between the east and the west have not reached the point of life and death. In fact, the political platform of the current President Zelinsky when he came to power is to reconcile the contradictions between the people of the east and the west (you can see from Russian polls It may also be possible that the positive attitude of the Russians towards Ukraine has also picked up).

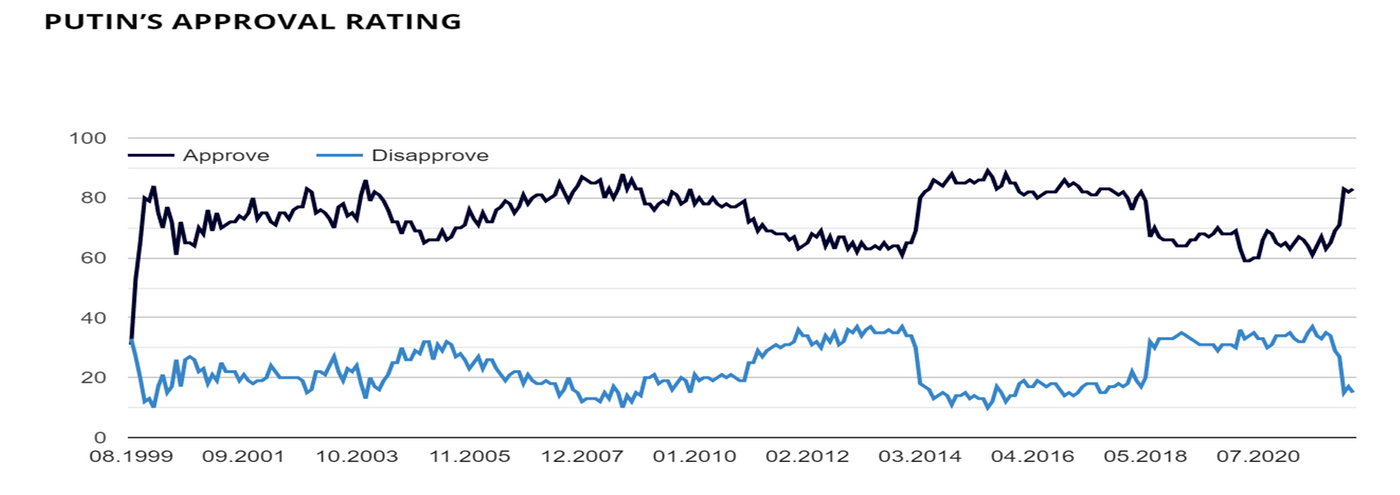

Others believe that it was Putin's personal adventure to divert internal conflicts. But if you look at Putin's personal support rate in Russia, you will find that it is quite stable so far. [2] At least until he invades Ukraine, we see no sign of any major political challenge for him.

So, why is Russia launching a war against Ukraine?

I think that when we exclude the above factors, historical merit becomes a possible candidate. Let's first look at what the Russians themselves say. The first is that Putin gave a speech on February 21 that seemed to me to be very strange. In this speech, Putin took a long time to describe the history of Ukraine, saying: "For us, Ukraine is not just a neighboring country. It is our own historical, cultural, spiritual space inseparable Part of it.” [3] He emphasized that Ukraine has no national tradition, and that modern Ukraine is a country artificially established by Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

If there are still ambiguities in Putin's words, the following words are clearer.

Here is an article published by a Russian news organization on February 26:

“Vladimir Putin’s decision not to leave the resolution of Ukraine to future generations is, quite literally, assuming a historical responsibility. After all, Russia needs to solve this problem. This is for two key reasons. National Security The problem, that Ukraine became an outpost of anti-Russian and Western pressure on us, is only of second importance in it. ... The number one cause will always be a complex of dividing the nation, a complex of national humiliation - the Russian family lost it part of the pillar (Kiev) and then had to accept the existence of two states, no longer one state, but two peoples. ... Now this problem has disappeared and Ukraine has returned to Russia. This does not mean that it statehood will be liquidated, but it will be reorganized, re-established, and returned to its natural state as part of the Russian world. To what extent and in what form will the union with Russia be ensured? This will be in the history of Ukraine's anti-Russian It will be decided after the end. In any case, the period of division of the Russian people will end.” [4]

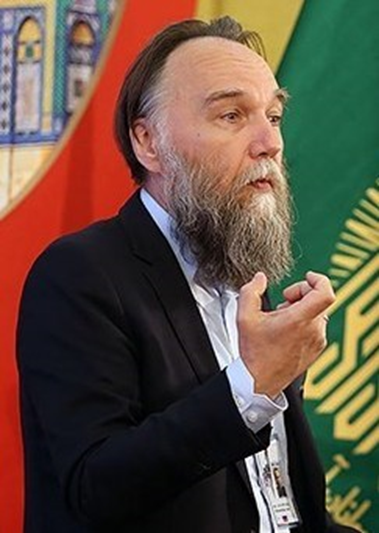

Alexander Dukin, Putin's personal philosopher, speech on February 26:

"Let us say goodbye to the Ukraine that Lenin created. And we are pushing de-communism to its logical limit... The attack on military targets in western Ukraine shows our determination to resolve this situation. I think it will end with these Ended with the unification of the Eastern Slavs of the region, the three branches of the Eastern Slavs (Little Russians, Belarusians and Great Russians) were united into one union and, as a whole, became part of the Eurasian Union. In my opinion, If we didn't have this goal in mind, we wouldn't take the extreme measures we have today. In my opinion, we should respect them, even if we are on both sides of the barricades. … Instead, say: 'Brothers, you understand that this Not our war (we support freedom and independence from any power, but we understand this better than you), we want you included in our empire, we are building a serious country, not a hysterical country like a clown .'"

Judging from their remarks, it is obvious that one of the purposes of Russia's invasion of Ukraine is to correct history and realize the reunification of the Eastern Slavs. In other words, what Putin wants to achieve is the historical achievement of "great unification".

So, why is Ukraine the object of this unification feat? We need to answer from two aspects: one is the historical relationship between Ukraine and Russia, and the other is the relationship between Russians and the empire. Why do we need to answer the second question, please wait a moment and I will elaborate.

two

Let's first review the historical relationship between Ukraine and Russia. Recently, there is a new book, Ploki's "The Gate of Europe", which describes the relationship between Ukraine and Russia in detail, and I recommend it to everyone.

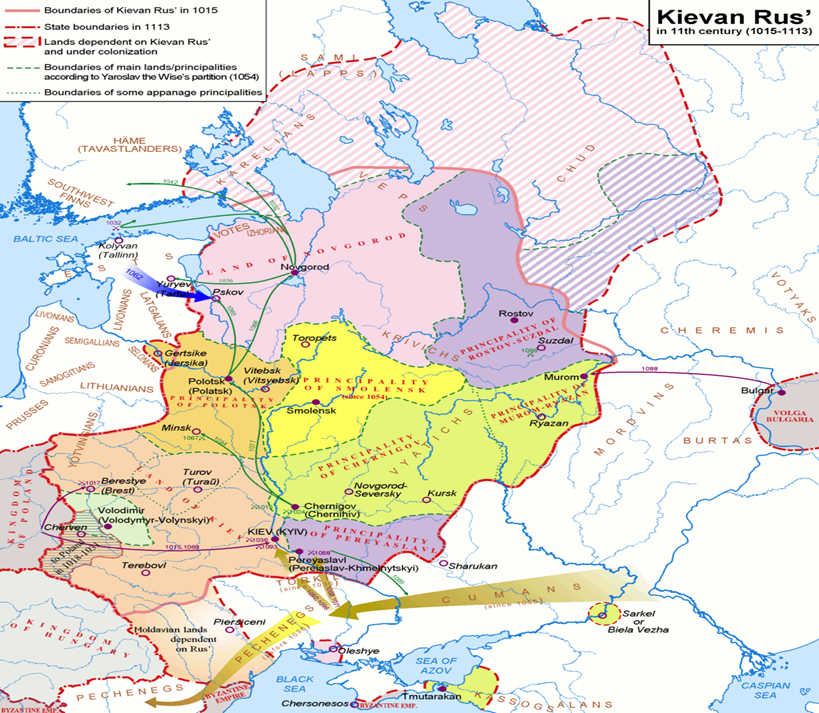

When we talk about the Eastern Slavs now, we always think that the Russians are the representatives and legitimacy of the Eastern Slavs, but this is actually a cover of reality over history. If we look at history, we will find that in Eastern Europe, the earliest and largest East Slavic country was the so-called Kievan Rus. In the middle of the Middle Ages, Kievan Rus was a very powerful Eastern European state. Unlike now that we think Russia's European identity is still more suspicious, at that time Kievan Rus had a much closer relationship with Europe. King Yaroslav of Kievan Rus has a nickname, "Father-in-law of Europe", because the rulers of various European countries are scrambling to marry his sister and daughter. One of his daughters, Anna, married King Henry I of France. When she married in Paris, she wrote to her father, saying that her new home was "a barren land with dark houses, crude churches, disgusting customs." [5] At least in Anna's eyes, Paris at that time was impossible. on a par with Kiev.

Kievan Rus was maintained from the 10th century until the middle of the 13th century. In its later period, the country was divided into several principalities, a bit like the Spring and Autumn Period of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty. Who is the successor of Kievan Rus? There are two, one from the east and the other from the west. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, Mongolia invaded, and the original principalities either perished or surrendered, and Kievan Rus perished. Decades later, taking advantage of the weakness of the Ross people, the Polish-Lithuanian state (the two countries merged in 1568) also invaded from the west, annexing most of the lands of what is now Belarus and Ukraine. At this point, the tendency of Ross's east-west division has been created. In the west is the Polish-Lithuanian aristocratic republic, presented to the world with the attitude of civilization coming from the West. In the east, there is the autocratic Principality of Moscow. This situation seems to be that after the collapse of the Tang Dynasty, the Song and Liao countries each claimed to be the successors of the Tang Dynasty. In China, there are Northern Dynasties and Southern Dynasties. In Ross, it is East Dynasty and West Dynasty.

Russia and Poland have been sworn enemies for a long time because of the competition for Ross's inheritance. Here is an example, after the Polish uprising of 1863, there was a famous and very influential intellectual in Russia named Mikhail Katkov, a well-known journalist, editor-in-chief of the magazine "Russian Courier" and "Moscow News" newspaper, calling for the use of all possible means to suppress the uprising. Because he believes that an independent, Catholic Poland will always bring challenges to Russia's nation-building, and the coexistence of the two will tear the hearts of many on this land. He said, "History always presents a matter of life and death between these two related peoples (Russians and Poles). These two countries are not just rivals, but incompatible enemies. sworn enemy". [6] It should be said that this attitude is not unique to Katkov, nor did it start at that time.

This Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was no different from the union between Castile and Aragon in Spain, or England and Scotland, as circumstances required. The Poles wanted to distance themselves from the Habsburg monarchs, the Lithuanian nobility admired Western civilization, and the Eastern Rus saw it as a protective force. For a considerable period of time, this aristocratic republic was the largest Slavic community on the border of Europe, and it was the common home of several different religions and ethnic groups. For a long time, everyone recognized the Polish brand and Polish culture.

For example, Joseph Clemens Piłsudski, the founding father of modern Poland, his parents were actually Lithuanian nobles (in view of the fact that the Lithuanian nobles are very Polished, they are actually not very different from the Polish nobles). His graduation career aims to revive the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and he is extremely painful for the failure of his ideal; another example is Vilnius, the capital of modern Lithuania. Lithuanian is spoken by only 1% to 2% of the population in the city (for the people of this large land, Polish is an elegant language, the language of intellectuals and aristocrats, and Lithuanian is a rural language ), Jews accounted for 40% of the city's total population. Coincidentally, until the early twentieth century, the proportion of Polish population in Lviv, an important city in modern Ukraine, was more than 52%, and 75.4% of Lviv residents claimed that their mother tongue was Polish. [7]

It can be predicted that if the Kingdom of Poland can survive the geopolitical shocks of the eighteenth century, and there is no "three divisions" among Russia, Austria, and Prussia (the three divisions of Poland from 1772 to 1795), then the Kingdom may be centered on Poland Unified nation building, like France and England.

However, the Kingdom of Poland is not without internal worries. In the early modern period, the Kingdom of Poland became weaker and weaker. First, its political system was too loose and divided; Between Ukrainians (Lithuanians are more equal to Poles). Ukrainian lower-class nobles and peasants were often dominated by Polish nobles and landowners (the middle and upper nobles were Polished). Timothy Snyder wrote in the book "The Reconstruction of the Nation" that after 1569, some Polish families acquired a large amount of land in Ukraine, and they brought a large number of Polish soldiers and Jewish assistants. So plunged into abject poverty, the complaint of the time was that "(Ukrainians) were regarded as inferior beings, and became slaves or handmaidens of Poles and Jews...". [8]

Because of this discrimination, a massive Cossack uprising broke out in Ukraine between 1648 and 1657. The Cossack leader of the uprising, Khmelnytsky, was a local noble in Ukraine and had a deep relationship with the Polish court. The original reason why Khmelnytsky led the Cossack uprising was because a Polish official stole his estate, occupied his lover, and murdered his son, and he himself appealed to the Polish court unsuccessfully. The reason why he was able to obtain a large number of people was also because the Polish nobles' occupation of the land caused a large number of peasants to flee to the border and become Cossacks. This Cossack rebellion can be seen as the expression of dissatisfaction with the lack of political rights (the resulting economic deprivation) by the military-armed Ukrainian nobles and peasants at the bottom.

Although Khmelnytsky claimed in 1648 that he was "the sole ruler of Rus," in Ukraine the nascent Cossack regime used Polish currency, used Polish as its administrative language, and even gave orders in Polish when fighting. From the beginning, the Cossacks' attempt was to fight for autonomy within the Polish state. Later, fighting against the Poles was unfavorable, and Khmelnytsky asked for help from all directions and surrendered. He asked for help from the Crimean Khanate, the Ottoman Turkish Empire, and the Habsburg Dynasty, expressing his willingness to surrender. Later, it signed a treaty with the Russian Empire, expressing its willingness to belong to the country, and the Russians agreed. Khmelnytsky could not read Russian. When he corresponded with the Russian side, he had to ask someone to translate the Russian letters into Latin before he could read them.

To be honest, the earliest saying that Russia and Ukraine have the same origin actually came from the Ukrainians themselves. At that time, the Ukrainian Orthodox priests in Kiev were very interested in attaching to a power that also believed in the Orthodox Church in order to compete with the Polish Catholic Church. So these priests compiled a chronicle in 1674, referred to as "Summary", emphasizing the existence of a unified Slavic-Russian nation in history. This statement was vigorously used by the tsars in the nineteenth century, and it has become a mainstream concept of Russians later and even now.

The semi-independent status of the Ukrainian Cossacks was maintained almost until the time of Empress Catherine. At that time, the Russians already called the left bank of Ukraine Little Russia. Ekaterina once emphasized the need to "Russify" Ukraine, "so that they will not be eager to return to the forest like wolves." [9] This "forest" should refer to Poland. The Russian Empire has always been wary of Poland and regards Ukraine as an intermediate area between Russia and Poland. Even after Russia, the Habsburgs of Austria and Prussia cooperated to carve up Poland at the end of the eighteenth century, this vigilance still persisted.

For example, after the Warsaw Uprising in Poland in November 1830, the great Russian poet Pushkin wrote in a poem:

"Where do we drop our defenses?

Do you want to retreat across the Buhe River? Back across the Volskra River? Up to the (Dnieper) estuary?

To whom would Volhynia belong then?

Who will be the legacy of Bohdan (that is, Khmelnytsky)?

If the right of rebel is recognized,

Wouldn't the Lithuanians also spurn our rule?

And Kiev, the old old city with its golden dome,

Ruth's father of cities--

Does it also let those sacred tombs

In the hands of barbaric Warsaw? " [10]

Pushkin asked aloud: "Will the streams of the Slavic countries flow into the Russian sea? Or will the Russian sea dry up, that is a question." [11]

On the Ukrainian side, due to the inherent contradictions between Ukrainian peasants and Polish landowners, many Ukrainians actually hold the so-called "Little Russianism", that is, they believe that the Ukrainian peasantry needs to ally with the Empire to protect themselves from Polish landowners and Catholicism. I believe that the Rus people are one family in the whole world. For example, Mikhail Yuzefovich, an important Ukrainian intellectual in the early and mid-nineteenth century, was a Little Russist. He was a friend of Pushkin and was wounded as an officer in the Caucasus. The work of the Kiev Archaeological Committee, responsible for documenting that Ukraine has always been part of Russia. The interests of the more Ukrainian-nationalist intellectuals at the time were still largely cultural. For example, Pavlo Chubynsky, the author of the Ukrainian national anthem "Ukraine Has Not Perished", who works in the Russian government, claimed in the report, "I have worked tirelessly in the North and proved my commitment to the Russian people. Love". [12] That is to say, his Ukrainian identity does not conflict with Russian identity.

After the mid-to-late nineteenth century, one incident greatly deteriorated the relationship between Ukrainians and Russia and changed the focus of Russia's Ukraine policy.

This incident is the Russian government suffering from the "Poland syndrome." Before the 1830s, the Russian Empire was very classical. Rather than saying it was a modern national empire, it might be better to say that it was an alliance of aristocratic classes. Its control over the territory is basically taking the upper-level route, using personnel relations to maintain imperial rule. After the Polish Uprising in 1863, the Russian Empire seemed to have suffered a huge psychological blow, and they had great doubts about the effect of their past leniency policies and the upper-level line. They began to reflect and worry that they were facing nationalist challenges. Many imperial rulers came to believe that increased administrative control and the eradication of alien cultures (in other words, Russification) were the only way out. One of the manifestations of this Polish syndrome is that the objects of the empire's suspicion, prevention, and suppression gradually extended from Poland to other ethnic groups in the empire.

In the western provinces (Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine on the right bank of the Dnieper) the main policy of the empire was to eliminate the traces of Poland in the region. Muravyov, then governor of the Vilna region (including Lithuania and Belarus) (it was he who suppressed the Polish uprising in 1830), said: "I decided to cut the Gordian knot with my sword , that is, the corrosive influence of the Poles on the rural population." [13] His approach was to eliminate the influence of Polish and Catholicism in administration, education and commerce, and replace them with Orthodox, Russian and Russian culture. As a result, the Ukrainian language cultural revival movement that had just emerged in the local area suffered a catastrophe. The Russian government called it a conspiracy by the Poles or the Jesuits, and they should all be banned to make way for the national language. Even if it wasn't, Ukrainian language, culture, and identity were seen as a threat to imperial unity: it threatened the integrity of the entire Russian nation no less than Polish nationalism.

The mainstream opinion in Russia at that time was to unify Russia, big and small. For example, Katkov denounced: "There is a sophistry claiming that there are two Russian nations and two Russian languages, just like there are two French nations and languages. Shameful and absurd.” [14] One Slavophile, Vladimir Lamansky, wrote: “The alienation of Kiev and its regions will lead to the disintegration of the Russian nation, the collapse and division of the Russian lands.” [ 15]

The Minister of Internal Affairs of the Empire, Petr Valuev, stated: "Any unique Little Russian language does not exist, has not existed, and cannot exist." [16] In 1863, the Ministry of Internal Affairs stated in a secret notice that the use of Books printed in Ukrainian. Shortly thereafter, the printing of Belarusian-language books was also banned, and the use of the Latin alphabet in Lithuanian publications was prohibited, allowing only the Cyrillic alphabet. In 1876, the empire banned the import of Ukrainian-language publications from Galicia, as well as theater performances and lectures in Ukrainian.

In short, it is to expand the anti-revolutionary campaign.

The empire's extra emphasis on Ukraine is also because Ukraine's position in the empire is becoming more and more important. In the early eighteenth century, Russia's population still accounted for more than 70% of the total population. However, with the large-scale expansion of the empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the population of the empire exceeded 170 million on the eve of the First World War, but the proportion of Russians in the total population of the empire dropped to less than 45%. Ukrainians make up 18 percent and Belarusians 4 percent. Therefore, the Russians would have to annex the Ukrainians and Belarusians to remain the majority. Of course, this is also due to the increasing status of Ukraine in the empire's trade and industry after the mid-nineteenth century (Ukraine's exports accounted for 75% of the entire empire), and a large number of Russian farmers migrated to southeast Ukraine to farm or work. The families of Khrushchev, Brezhnev and Gorbachev all migrated to Ukraine in this wave of immigration.

Due to the "expansion of counter-revolutionaries", the new Ukrainian generation is gradually radicalized. For example, Mykhailo Drahomanov, a professor of ancient history at the University of Kiev, was originally an intellectual interested in the field of culture. He actually criticized the narrowness and chauvinism of Ukrainian nationalism. , he was expelled from Kiev University in 1875 and then went into exile in Switzerland. There, he wrote a large number of works, preaching the uniqueness of the Ukrainian nation, advocating reforming the empire to establish a federal government, and becoming a very influential Ukrainian political thinker. What happened to him is actually the common experience of a group of Ukrainian intellectuals. By the 1880s and 1890s, it could be seen that "Little Russianism" was gradually becoming marginalized among Ukrainian intellectuals.

Leonard Lundin, an expert on the history of Finland, summed up the Russification movement in Finland, saying: "No matter how reasonable some of the reasons for Russification may seem at first, the development of Finland has proved it. This calculation is fundamentally wrong. A largely loyal nation has been alienated, Finnish national consciousness has been strengthened, and an enemy has been unnecessarily created.” [17] The same conclusion applies to Ukraine.

Another thing worth mentioning is that part of the land in western Ukraine is now under the jurisdiction of the Austrian Habsburg Dynasty-Austro-Hungarian Empire, which is the product of the "three kingdoms". The rulers of the Habsburg dynasty also regarded Polish nationalism as a worry, but their approach was far superior to that of the Russian Empire. They correctly realized that the Ukrainians and Poles were not to be dealt with, and that the rule of the empire did not need to be uniform. Therefore, the Austrian Empire was quite loose in governing this land, encouraging local Ukrainian cultural and political organizations. In this way, the nationalisms in the east and west of Ukraine prospered for different reasons, stimulated each other, and finally merged after the First World War to establish the "Central Rada" and the first Ukrainian republic.

When the Bolsheviks came to power in Moscow, they sent a large army to attack Kiev, but they were repelled. Later, a war broke out between Soviet Russia and Poland, and they were defeated. The land in western Ukraine was assigned to Poland. In this way, Russia and Poland once again formed such a situation of ruling across the river (Dnieper River).

Lenin was quite a pragmatic person, although he was ultimately quite anti-federalism, but the Bolsheviks were a small party, and at this time they were under siege, and compromises were inevitable, so they established the so-called Ukrainian Socialist Soviets Republic, open the door to the Ukrainian left to join the party. This move is actually not as revolutionary as we imagined, but it echoes the old tradition of the Russian Empire, that is, to rule a local area, it is necessary to cooperate with local social elites, grant local privileges, and absorb them administratively.

Everyone knows the subsequent history of Ukraine, so I won’t repeat it here.

The above is the cause and effect of the establishment of the Ukrainian state. To sum up, we can know three things: First, Putin’s claim that Ukraine is a country artificially created by the Bolsheviks is half true and half false. Rather, Ukraine is a natural product of a series of historical and political movements. Lenin and the Bolsheviks are just Second, Ukrainians and Russians are indeed entangled with each other. You can say that they are a community of people, or that they have two branches of flowers. The difference between their ethnic groups depends entirely on political promotion (this is why despite Ukrainian The Great Famine and the Chernobyl accident, before 2014, many Ukrainians were still optimistic about Russia, and there were always East-West factions in Ukraine); Third, the Russians have so-called historical achievements in Eastern Europe, and the Russians The unity of the Ukrainians, Ukrainians and Belarusians and the inheritance of Kievan Rus are buried in the genes of the Moscow state.

three

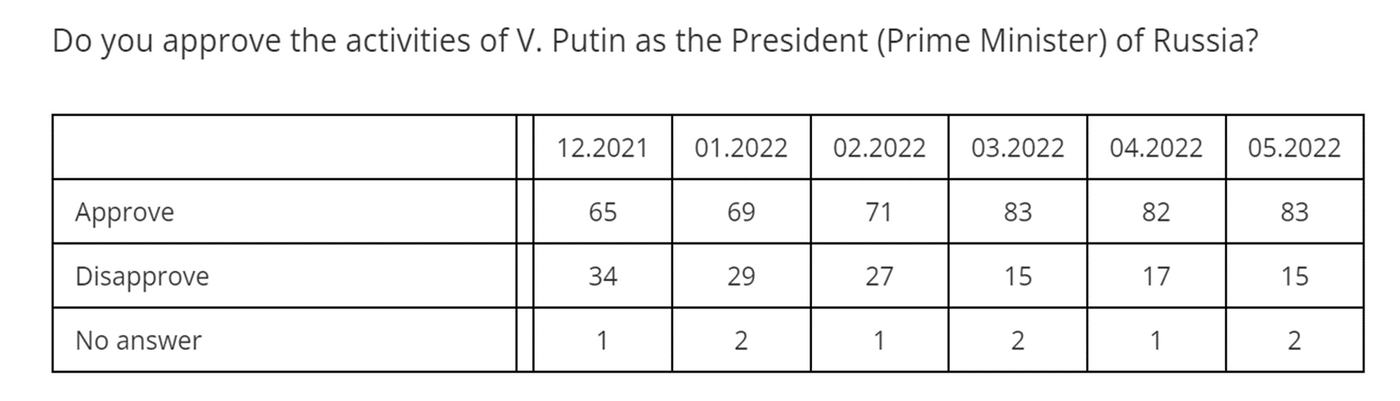

But the above content can only explain the fantasy that Putin may have historical achievements, but it cannot explain why the Russians still support Putin and this war. For example, the following survey conducted by the Levada Center, an independent Russian survey agency, in April showed that Putin's approval rating still stood at 82%, the highest level in four years. [18]

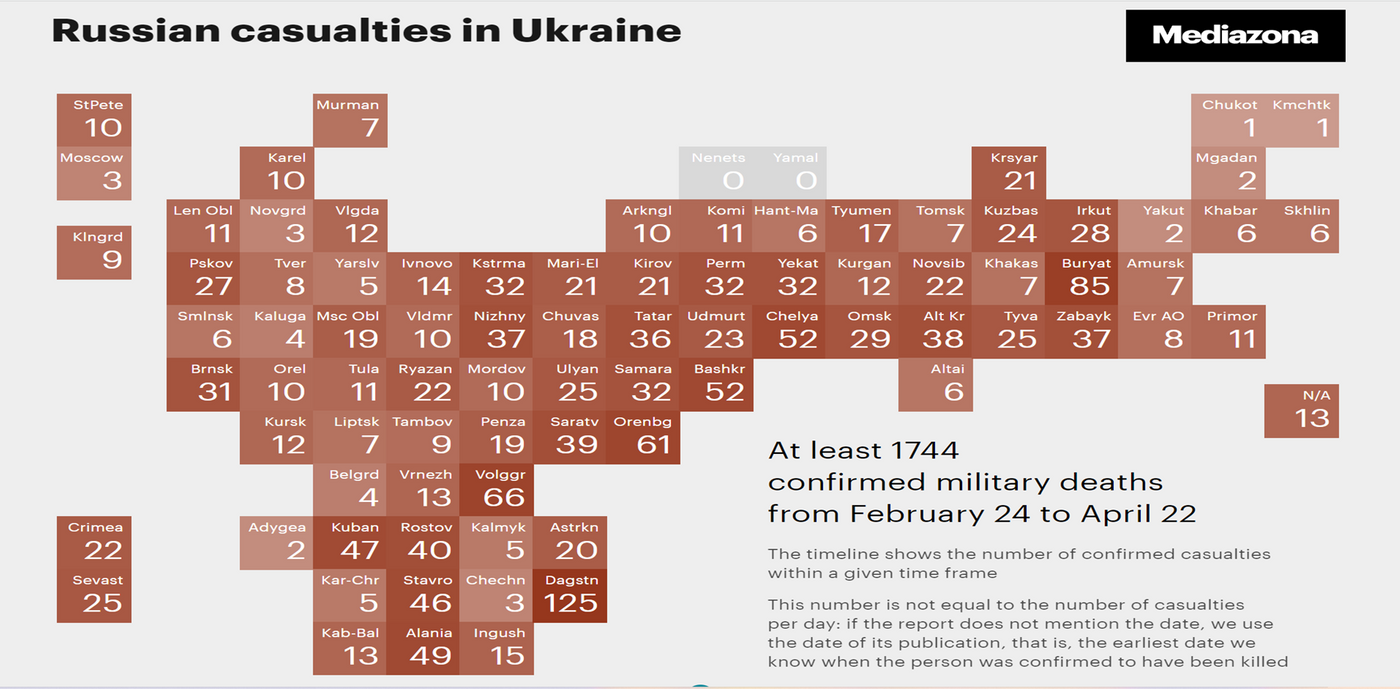

Please also consider the fact that in 2019 Putin's approval rating was as low as 31%. On the other hand, Russia's own published data shows that ethnic minorities from impoverished areas account for a disproportionately high number of Russian military casualties reported. As a city of 12.5 million people, Moscow has only three deaths, but there are abnormally many people from places like Dagestan and Buryatia. [19] In the fighting ranks of the Russian army, we can also see a large number of Chechen mercenaries and Luhansk and Donetsk militias. This war launched by Putin has a taste of using barbarians to control barbarians.

Looking at these two aspects together, there is probably some kind of collusion and exchange. Although we can say that Russians have a high support rate for Putin because of the low number of casualties in the central area of Russia (or Putin has consciously reduced the number of casualties in the central area), but I still think this relationship should be reversed, that is, Putin is backed by Russia's center at the expense of people on the periphery. This complicity and exchange is also reflected in Putin's slow reluctance to carry out a national mobilization.

In general, I think that Putin's war in Ukraine was genuinely popular with a significant portion (maybe most) of Russians, and that this welcome was rooted in Russians' historical resentment - both in the Tsarist During the Russian period, or the Soviet era, Russian nationalism was in a state of being obscured. For quite a long time, Russians have felt that they are not the masters of their own country.

In short, why do Russians have the urge to conquer Ukraine? The answer is "imperial trauma", which is related to the relationship between Russians and their own country (empire) in history.

Let's start with Tsarist Russia. Compared with Britain, France, and the Habsburg Empire, a remarkable feature of the Russian Empire is that for a long period of time, there was no "imperial nation" in the empire. The so-called imperial nation refers to the fact that within an empire, there is a certain ethnic group that occupies a dominant position in politics, economy, society and culture, and the empire belongs to them to some extent. Some people may immediately retort: how could it be? Doesn't the Russian Empire belong to the Russians? Aren't the Russians the main population of this empire?

No, that's not the case. The answer can be roughly summarized as follows: Although the largest group of people in the empire are Russians, and they are also the main force of the empire’s conquests, but the Russians as a group do not “enjoy” the empire—this refers to the empire’s The cost was unequally distributed among the Russians, which also meant that ordinary Russians were not socially, economically and culturally superior (reich policy did not favor them).

First of all, of course, it means that Russians enjoy less political and social freedom than certain ethnic groups in their territory. Russians, for example, clearly have less freedom, not more, than Finns, who have a constitution and a parliament, while Russia does not. In Ukraine there is no serfdom, but in Russia there is.

Second, non-Russian residents enjoy somewhat more legal/political privileges than ordinary Russians. For example, non-Russian residents were exempt from military service until Russia established universal military service in 1874. Even after 1874, Caucasian, Finnish, and Poles had shorter service periods than Russians, and ethnic groups in Siberia and Central Asia were also exempt. Take the Jews again, although they were sometimes forced to live in ghettos, they were not in danger of becoming serfs.

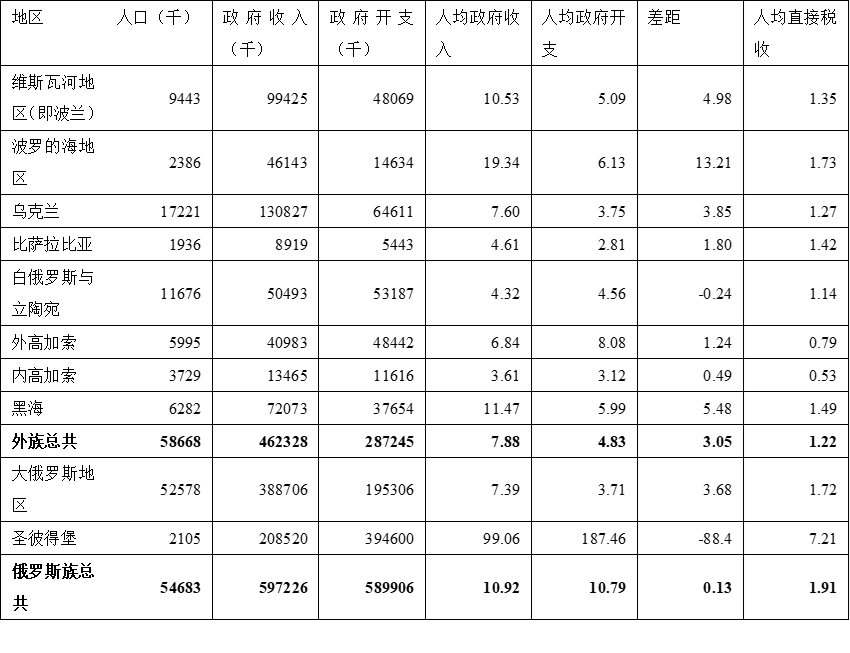

Third, non-Russian residents generally pay less tax than Russians. The following table shows the government revenue/expenditure and taxation of the various regions of the Empire in the 1890s:

From the above table, the per capita direct tax paid by Russians (1.91) is more than 50% higher than that of non-Russian residents (1.22). In terms of overall government income, the burden of Russians is almost 40% higher than that of non-Russian residents. Although the empire also spent a lot of money in the Greater Russia region, the money was mainly used to meet administrative expenses, not to invest and provide public services, so the Russians did not get any benefits. Please note that this larger expenditure is mainly due to the fact that the empire spends all its money in Petersburg. Outside of Petersburg, the government spends less money (3.71 rubles per capita) than in non-Russian regions ( 4.83 rubles per person).

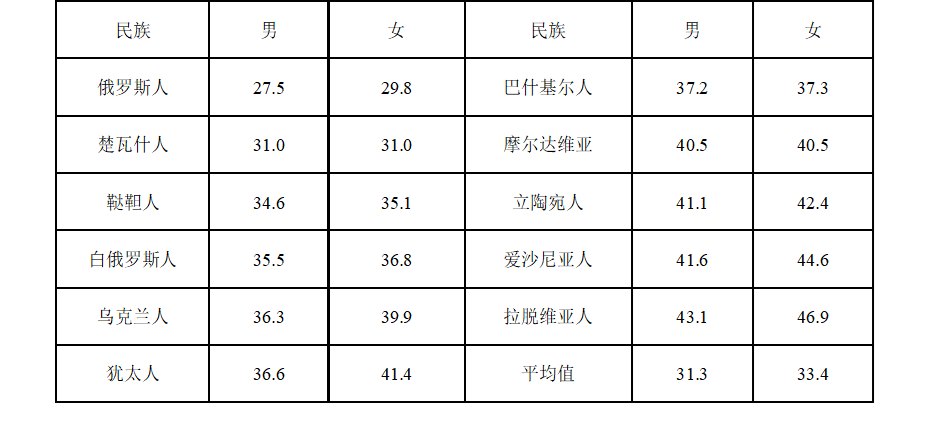

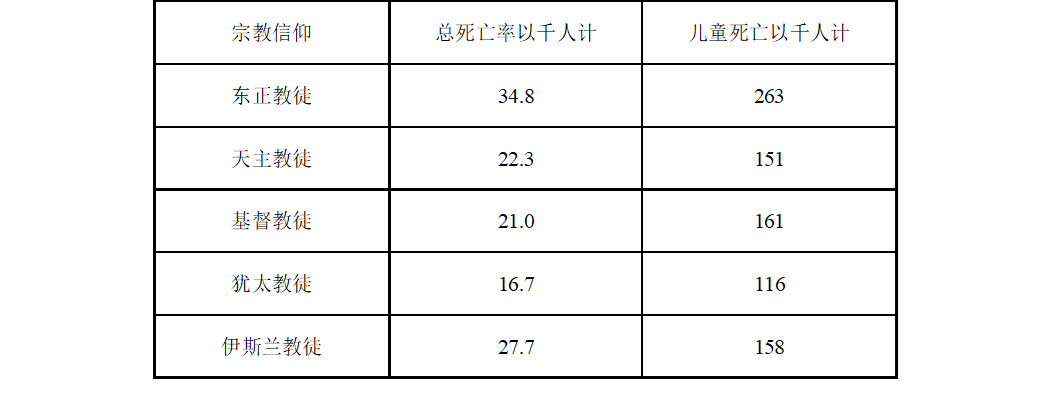

This tax discrimination is not due to wealthier, more economically developed, more industrialized/urbanized Russian regions. On the contrary, compared with many ethnic groups in the empire (such as Germans, Poles, Jews), Russians are far inferior in terms of literacy and economic and social achievements. Moreover, not only compared with the more developed population in the west, the Russian public is no better than the eastern and southern remote areas. At the turn of the nineteenth century, for example, Russians had lower life expectancy not only than Baltic populations, Jews, and Poles, but also Ukrainians, Belarusians, Tatars, and Bashkirs. The infant mortality rate of the population of Greater Russia was significantly higher than that of the rest of the empire. See Tables 2 and 3 [20] .

Again, from an economic point of view, the economic interaction of Russians with non-Russians is hardly exploitative (except for the fur trade in Siberia, mining in the Urals, the victims of which are indigenous peoples of Siberia and Bashkirs). In the northwest of the empire, it was the Baltic Germans who controlled trade, in the west it was the Jews and Poles, and in the south and east it was the Greeks, Armenians and Tatars. Since the 17th century, Russian merchants have been protesting the privileges the empire grants to foreigners and non-Russians. The Swiss historian Andreas Kappeler thus draws a conclusion - "Considering the financial privileges of certain non-Russians and the huge government spending on the army and administration, until the nineteenth century Most of the non-Russian outskirts made little profit.” [21]

Finally, judging from the self-perception of the imperial rulers, they may not have much Russian national identity. They may be aware of their Russian roots, but they will hardly think that they have anything in common with ordinary Russians. . American historian Kumar pointed out that the Russian monarch itself is hardly a Russian. "The Romanovs were hardly Russian...they lived the lives of westernized aristocrats. They used German court manners, their parks and palaces were neoclassical...even by blood they were hardly Russian , which was the result of endless intermarriages with the German royal family (this refers to the Russian tsars after Peter I, all of whom had foreign wives, especially Germans)." [22] Other European royal families, although they also have foreign blood, usually have foreign wives. They all seem relatively low-key. But the Russian tsars always seemed to be emphasizing their foreignness. The language of the court was French at first, and English was added later. Although Tsar Nicholas I once said that he hoped that all the people ruled by the Tsar would one day be able to "speak Russian, act like a Russian, and feel like a Russian", [23] During the period, his Minister of Education Sergey Uvarov (Sergey Uvarov) put forward a slogan - Orthodox Church, Monarch and Nation (sometimes translated as Orthodox Church, Despotism and People's Nature) as the school education policy. This slogan later became in fact the official ideology of Tsarist Russia. Uvarov's national definition of Russia is: "The Russian nation is not a race, but a cultural community united by infinite loyalty to its own regime. Western nations.” [24] In other words, orthodox churches and monarchs should be ranked above nations.

Nor was the employment of the imperial bureaucracy favored by Russians. One of the most famous generals of the empire, General Alexander Suvorov, was a nobleman of Swedish descent, and another great warrior, Prince Peter Bagration, was of Georgian royal family. According to statistics, among the 2,867 bureaucrats who occupied the top positions from 1700 to 1917, 1,079 (37.6%) were of foreign origin. Of these, 355 were of Baltic German origin. [25] The state council (also translated as the Senate) of the last Tsar Nicholas II had a total of 215 people serving between 1894 and 1914, of which 61 (28.3%) had obvious foreign backgrounds (including 48 had German ancestry). [26] Therefore, the Swiss historian Andreas Kappeler (Andreas Kappeler) summed up the Russian employment tradition in this way: "Before the First World War, the tsarist government always valued loyalty, professional knowledge and noble lineage". [27]

So, as the Cambridge History of Russia points out, "until the middle of the nineteenth century, tsarism was not so much a Russian national regime as a dynastic aristocratic empire. As often happened in premodern empires As stated, Russia's core population was in some ways more exploited than the marginal minorities. It is clear that the Baltic German, Ukrainian, Georgian, and other aristocrats benefited far more from the empire than the Russian masses. " [28]

To sum up, we can boldly say that there is no "imperial nation" in the Russian Empire, and this is where the Russian Empire is very different from other modern empires. In many ways, Russia is not so much a colonial country as it is a colonized colony. Russians unfairly carry the burden of the empire without "enjoying" it. From this perspective, some historians have even proposed a concept that Russia is a "self-colonizing" empire. British historian Alexander Etkind (Alexander Etkind) pointed out that Russia is not only the subject of colonization, but also the object of colonization and the product of colonization. [29]

Although the Bolsheviks overthrew the rule of Tsarist Russia. But as Tocqueville pointed out in the book "The Old Regime and the Great Revolution", the new regime is inherited from the old regime, and in some respects it will be similar. When Professor Liliana Riga of the University of Edinburgh was studying the composition of the Bolsheviks, she discovered an interesting thing, that is, among the early senior leaders of the Bolsheviks (93 members of the Soviet Central Committee from 1917 to 1923) there were Strong ethnic minority - Jews, Latvians, Ukrainians, Georgians, Armenians, Poles and others make up nearly 60% of it, while Russians are a minority.

If one looks at the place of origin, Liliana Lijia found that only a quarter of the Bolshevik leaders were born in the core area of the empire, and the rest were from the border areas. If you look at occupations, most of the Russian Bolsheviks were workers and peasants, and most of the middle-class Bolsheviks were foreigners. She couldn’t help asking herself: Is it true that we saw the Russian Socialist Revolution as a class revolution led mainly by Russian intellectuals against an autocratic government?

Russian social historian Boris N. Mironov also made similar observations. He made statistics on the national conditions of the 7,000 most active revolutionaries who were exiled to Siberia from 1907 to 1917. The proportion in the population was compared with the proportion in the revolutionaries, and the same conclusion was drawn: if the revolutionary enthusiasm of the Russians is 1, then the Latvians are 7 times higher than the Russians, and the Jews are 3 times higher. Poles are twice as high, Armenians and Georgians are twice as high. Mironov also pointed out that before the 1870s and 1880s, most of the revolutionaries in the empire were Russians. This was because the socioeconomic status of Russians was lower than that of non-Russians. Nationalities (except the Poles) who showed loyalty to the authorities began to become the number one force in the revolution. [31]

Of course, the slogan and content of the Bolshevik Revolution was indeed a class revolution, but the goals and mobilization mechanisms of the revolution could be completely different. Who was more likely to believe in Bushelism and join the revolution in the first place? [32] Lijia pointed out that it was the border policy of the empire in the late nineteenth century that contributed to Bolshevism-in short, the frontier policy of the empire created a large number of rootless people. They were educated Russified and separated from their native groups, but were politically, socially and economically excluded from integrating into the empire. So they cooperated with the Russian workers and peasants who also suffered the price of the empire, joined the supranational Bolshevism, and launched a radical revolution.

From this perspective, Bolshevism was not as revolutionary as it appeared, but to some extent echoed the old traditions of the Russian Empire (although the class cooperation was reversed). Just as Tocqueville pointed out in his book "The Old Regime and the Great Revolution" the succession of the post-revolutionary French system and the ancien New Class" coalition.

In the Soviet era, the situation has not changed much. Although the Soviet Union suppressed local nationalism during the Stalin period, the national system of the Soviet Union basically did not undergo major changes.

In the past, when we talked about the national system of the Soviet Union, there were generally two theories. One theory, as stated in "A Personal Experience of the Disintegration of the Soviet Union", is that the Soviet Union is only "on the surface a state/national federation, but in fact there is a centralized political party behind the federation." On the surface, all ethnic groups have their own union republic and nominal autonomy, but "this theory is just an illusion. In fact, this country has always adopted a single form of rule, and national and local interests are not the principles it considers The reason for this is that these constitutional entities have no actual political power, and all political power in the Soviet Union is concentrated in the hands of the Communist Party, and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union is organized in a highly centralized manner, although other countries except Russia The union republics all had their own communist parties, but these parties were viewed by Moscow as the provincial branches of a single organization. It was this single party that formed the backbone of the Soviet autocratic structure, with the republics and other entities merely an embellishment. It looks good, but it doesn't have a structural function." To sum up, it is "nationalism in form, socialism in essence." [33] . The author points out that other nationalities in the Soviet Union were often strongly influenced by Russification or "de-indigenous culture". Another way of saying it, as Henry E. Hale (2005) and Yuri Slezkine (1994) put it in their respective articles, is that the Soviet Union was just a ", each nation has its own room, national rights are real, not false; economically, Russia is actually subsidizing other nations; the Soviet Union collapsed because of the independent political power of the republics The system provides a political base for separatists of all nationalities to exploit.

To be honest, both statements are true and not contradictory. In the past, when we looked at empires, we always liked to start from an inter-ethnic perspective and regard it as the colonial oppression of one nation on another. But in fact, in many empires, the rulers of the empire could not care whether they ruled the same race or a different race. They also don't mind teaming up with rulers of other ethnic groups to "cut leeks". In such an empire, from the perspective of vertical power relations, the elites of the minority groups are vassals of the elites of the majority group, and major national policies are formulated and implemented at the center, but from the perspective of horizontal power relations, the empire appears to respect the periphery. Regional (elite) privileges (to maintain common rule, indirect rule). In this way, viewed vertically, it is authoritarian, but viewed horizontally, it appears to be "autonomous" and "cooperative". Whether it is Tsarist Russia or the Soviet Union, to some extent, this is the case.

I also want to say here that because some Western scholars have lived in a democratic country for a long time and lack the experience of living in an autocratic country, they often cannot understand that there is such a thing as "reverse discrimination and isolation" in this world. They don't understand: In some countries, the rulers are above all ethnic groups and are not dominated by any ethnic group. They can use reverse discrimination to balance the relationship between ethnic groups to stabilize the situation and reduce the burden of the empire to the number of people. more than that nation. From the outside, it seems that small ethnic groups are enjoying special treatment, above the larger ones. In terms of consequences, this not only has the effect of maintaining stability, but also creates necessary contradictions among the people.

In this way, in the era of Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union, Russians did not feel that they were the masters of the country, but the objects of reverse discrimination. It was inevitable that they would feel resentment in their hearts, and at the same time, some thoughts of retaking the country gradually emerged. movement and rhetoric. They demanded to be masters of the empire, to make it work for them. In short, Russian nationalism has been overshadowed by Tsarist Russia and the Empire for a long time, resulting in "imperial trauma" and "imperial longing".

Below, I briefly tease out this evolution of Russian nationalism.

The first wave of Russian nationalist movements was born in the mid-nineteenth century. At that time, Tsar Alexander II carried out a series of liberalization reforms, and the so-called public sphere and civil society appeared for the first time in Russia. But the reality is that the emergence of a freer and more independent Russian society is accompanied by the awakening of Russian nationalism. At that time, the Russian intellectual circles could be divided into slavophiles and anglophiles based on pro-Western or traditional conservative attitudes, but neither faction contradicted the rising Russian nationalism. Westernizers certainly hope to liberalize the empire so that the middle class and ordinary people can participate in national politics. However, what they looked up to and studied at the time were nation-states with neat political systems such as Britain and France. They opposed the traditional special rights enjoyed by many non-Russians in the empire, believing that this was a manifestation of the dynasty’s oppression of Russians. As for Slavism, it was originally just a literary school in the 1820s, with a rather romantic imagination of Russian history and culture, and later evolved into a kind of organic nationalism, which has quite complicated meanings. [34] Personally, I think that Slavism can be seen as a kind of resistance of Russians to "colonization". For Slavophiles, the Slavic sub-ethnic groups living in the western part of the empire are too deeply infected by Western culture and values and need to be corrected. [35] In this way, the Russian intellectuals came to the same conclusion from different standpoints. They did set off a persistent wave of nationalist thought within the Russian Empire.

The second wave of nationalism will wait until around the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union. In early January 1990, a young author named Alexander Prokhanov published an article in the "Russian Literary Journal" attacking Gorbachev's leadership for weakening the foundations of Soviet unity. The U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union at the time was amazed to see the ghosts of the old days reappearing on the stage of Russian thought, "These imperialists, who called themselves Russian 'patriots', often espouse the most disgusting things about Tsarist Russia. ...All these people believe that Russia has the mission to rule the vast area from Constantinople to the Pacific Ocean, from the Baltic Sea to India, and to achieve hegemony in all the peripheral areas. They believe that the Russian Empire is the Russian nation The mark of the empire. Preserving the integrity of the empire should take precedence over personal interests, over the interests of peoples other than the Russian nation.” [36]

By the 1990s, this Russian imperialism came to be known as "Neo-Eurasianism." A representative figure of this new Eurasianism is Alexander Dugin. New Eurasianism has its predecessor "Old Eurasianism", which was created by Russian exiles in the 1920s. It is an anti-Bolshevik and anti-Westernizationist constitutional democracy, but emphasizes that Russia has a unique personality With Destiny, it can basically be seen as some kind of Russian conservatism. Compared with his predecessors and peers, Dugin's New Eurasianism is much more thorough in terms of anti-Westernism and much more radical in terms of geopolitics. He advocates the establishment of a so-called Eurasian Union. This Eurasian Union is actually a reprint of the Russian Empire. Dugin himself believes that Russia is an empire in history, and it must be an empire. It was born with the important task of leading the Eurasian region. [ 37] Dugin said in his early book "Principles of Geopolitics": "There is no way to imagine what Russia will be like if it is not an empire. It is destined to become an empire." Asianism began to play a central ideological role in the Putin government. So much so that Du Jin was called "the most dangerous philosopher in the world" by the American media in 2016. [39]

Obviously, it is not just a few scholars who have this imperialist orientation. Mikhail Bulgakov, creator of The Master and Margarita, insists that Ukrainian is a "non-existent, vile language". [40] Alexander Solschenizyn, the author of The Gulag Archipelago, was not anti-tsarist Russia, although he was very anti-Soviet. "In the 2000s, Solzhenitsyn met Putin several times, and the two agreed that the East Slavic unity of Belarus, Ukraine and Russia must be restored; both were convinced that Western democracy as a form of state polity was harmful to Russia. " [41] Joseph Brodsky, a Nobel laureate who was also persecuted by the Soviet Union, denounced Ukrainians in his 1992 poem "On Ukrainian Independence," saying : "When it's your turn to die, you big idiots, you scratch your mattresses with screeching noises and recite Alexander's (Pushkin's) maxims instead of Taras' gibberish. (Taras Scher Vchenko, nineteenth-century poet, one of the founders of modern Ukrainian language)". Like Pushkin, these people can be said to be Russian intellectuals with conscience, but at the same time they also have a real "imperialist" mentality.

We can reasonably guess that at least a considerable number of ordinary Russians hold similar views and psychology to the above-mentioned people. Given that Russian support for Putin's war in Ukraine may be quite real, it seems reasonable to guess that the war will not end so easily, that Putin is unlikely to be overthrown by a coup, a street demonstration. We may have to hold the expectation of protracted war.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!