Living Communism: Theory and Practice of Autonomy and Attack

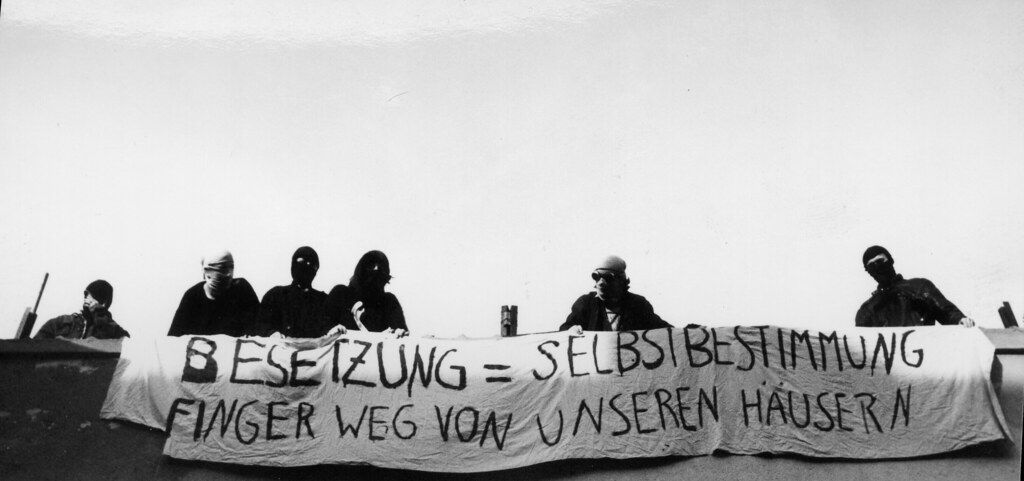

May Day 1987: Thousands of black-clad Autonomen ("self-governing") riot in West Berlin. After a decade of street struggle, they have fought state repression by blocking streets, occupying buildings, and engaging in low-intensity urban warfare with the police. The Autonomen expand their liberated zone across much of the Kreuzberg neighborhood, their base. After a night of rebellious revelry, they return to their squats and social centers to nurse their wounds, curse the police, and celebrate their temporary victory. While the German media portrays the Autonomen as violent thugs whose only motive is destruction, the activists simultaneously build an extensive network of squats as an alternative infrastructure in West Berlin and across Germany.

In the 1980s, the Autonomen transformed hundreds of abandoned buildings into collective housing, social centers, event bars, and cultural centers—spaces that provided both alternative forms of life and bases for attack. At their peak, squats constituted urban liberation zones in which thousands of young people practiced the communism of everyday life. More recently, in France, the Invisible Committee has drawn on the German experience of autonomization to theorize the Commune as abolitionist spaces of everyday communism. According to this view, the Commune does not constitute a constitutional state of a new order that aims to establish more representative state institutions. Instead, according to Giorgio Agamben, the Invisible Committee argues that the Commune impoverishes the state (i.e., renders it inoperable and impotent) by challenging the need for state institutions. The development of new forms of communal life outside of the state and capitalism provides the basis for “repressing them in an active way.” Abolition is not primarily an attack on the institution, but an attack on our need for it. It is in this sense that the Commune provides the material basis for “living communism” and an attack on the domination of capitalism and the state.

The Invisible Committee is a collective of post-autonomist communists (formerly operating under the name Tiqqun) who trace their intellectual genealogy through, among other places, the Italian Autonomia and the German Autonomia. Although they were born in the Parisian squatting scene, they became disillusioned with the radical subculture milieu and moved to the small town of Tarnac, where they lived communally and operated a farm, bar, and grocery store together. They were introduced to the American popular imagination primarily through the controversy surrounding their book The Coming Rebellion (2007, 2009), as well as engagement from friendlier groups such as Endnotes and Crimeth Inc. The Invisible Committee continued to develop their particularly varied theory of post-autonomist communism in To Our Friends (2014), which reflects on the European Square movement and related spectacular, short-lived rebellions (particularly in Greece). Their latest work, Now (2017), explores the possibility and practice of communism in a fragmented capitalist world. While the group is relatively widely read, their historical and theoretical background is little known in the United States.

This article combines the historical insights of the Autonomen and the theoretical interventions of the Invisible Committee to advance several related arguments. First, the communal form creates alternative worlds in which liberalism is combated and the struggle against alienation is waged collectively. Second, the communes operate according to a unique spatial logic that breaks with capitalist geographies, promotes new spatial practices, and establishes non-alienated dwellings. Third, the Autonomen and the Invisible Committee theorize and act on new conceptions of communism as a collective practice of living the ‘good life’ in revolutionary struggle rather than simply as a (future) economic system. Fourth, alternative infrastructures provide the means to practice this in everyday life. Finally, revolutionary practice requires networks of autonomous communes to break away from the capitalist system and form liberated territories as a basis for attacking capitalist state power.

1. Commune form

“The Commune is the fundamental unit of true reality… All power belongs to the Commune!”

- The Invisible Council, The Coming Rebellion

Communes are centered around two core components: an anti-individualistic collective bond and the resulting radical transformation of everyday life. In the liberal ideology based on the capitalist market, human society is reduced to unfettered individuals in perpetual competition. In the face of this atomization, communes are formed around the desire to undertake collective projects. Communes emerge when we change our relationship to each other and face the world together. As defined by the Invisible Committee, "The basis of the commune is a mutual vow... that unites them ... The commune is an agreement to face the world together. Its own strength is a source of freedom. It is not a thing to be achieved: it is a way of connecting and being in the world ." Communes build community in isolation and replace individualism with collective self-determination and well-being. They form when a group of people try to directly "live" their lives together (giving them something in common) and face the world's problems together.

Although capitalism has colonized every aspect of our lives, it is possible to resist and collectively build alternatives. As radical geographer Alexander Vasudevan puts it in his book on squatting in Berlin, “squatting is a place of collective world-making ; a place to imagine alternative worlds… What is at stake here is the opportunity to build an alternative habitus , where the practice of ‘occupation’ becomes the basis for producing a different sense of urban life.” Thus, the Invisible Committee argues that communes are a “form of life that is immediately organized for sharing” according to alternative values. As one activist put it, “the desire for autonomy means above all a struggle against political and moral alienation in life and work… it means taking back our lives.” Furthermore, as historian of the autonomous movement George Katsiaficas explains, “ autonomous communities seek to live according to a new set of norms and values within which everyday life and all of civil society can be transformed. Starting from overt political beliefs, they seek to transform isolated individuals into collective members who can enter into equal relations… their collective form negates atomization.” Autonomous communities organize around these collective values and everyday practices, rather than rigid ideologies or parties.

Autonomen approach everyday life in light of their values of self-determination, equality, and autonomy. Drawing on the Italian Autonomies and the German Autonomist women's movements, they adopt a "first-person politics" rather than a Marxist orientation toward the proletariat or an anti-imperialist Third World national liberation orientation. In line with this fundamental belief, Autonomists emphasize self-determination within subcultures rather than traditional workplace struggles, embrace a "fuzzy anarchism," and call for "no one to have power." Although they criticize "alternative movements" for their willingness to coexist with capitalism, they emphasize the need to build alternative worlds that form the basis for resistance to the ruling order. Autonomists organize into small, non-hierarchical groups that collectively confront everyday problems and come together for larger actions. They seek to establish the possibility and reality of autonomous, lived communism.

2. Commune space and cultural production

“Everything that claims to be a commune generates a new geography around it—sometimes even at a distance.”

– To our friends at the Invisible Committee

Communes challenge the spatial order of the capitalist world, establishing inhabited territories and providing context for experimental spatial practices. Social space is important to contestation because it has important material and ideological functions for liberalism. As the Invisible Commission explains, “We have inherited the modern idea of space as an empty, regular, measurable extension occupied by objects, creatures, landscapes. But the perceived world is not presented to us in this way, space is not neutral… These places are irreducibly loaded with history, impressions, emotions.” Capitalist space appears as an apolitical, static stage in which historical narrative events take place. But neoliberalism has fragmented capitalist space, and the Invisible Commission has identified a “new spatial order of the world.” In their recent work, they have identified fragmentation as a defining feature of contemporary social life, arguing that “we are the generation that has caught up with the process of civilization reversing into a process of fragmentation.” Fragmentation occurs at every level: Fordism becomes post-Fordism; the modern capitalist spatial organization of cities is fragmented; the last remnants of collective, social, and non-market values are destroyed as human fragments become “demand opportunists” interacting through screens. This fragmentation provides the situation for the Commune’s participation. The Commune challenges fragmentation while mobilizing it to achieve new, inhabited spatialities.

The Commune propagates a logic of settlement in response to the dispersed, unmoored flows of capital. Over the centuries, capital has become increasingly detached from material territory. Against capitalist abstraction,

The commune sees itself as a concrete, situated rupture with the global order. The commune grows in a specific territory, which means that the commune shapes the land, and the land provides the commune with a place to live and shelter. The commune weaves the necessary connections there, nourishes itself with its own memory, and finds meaning and language with the land... A living territory will eventually become an affirmation, an explanation and expression of the things that live there.

Communal dwelling aims to make territory impermeable to dominant power. By increasing the number of free spaces, deepening the connections and circulations between them, and overcoming our dependence on capitalist infrastructure, “the goal is to make territory invisible and indefinable to the powers that be. It is not about occupation, it is about territory.” This is the opposite direction of liberalism and capitalism’s approach to space.

Communes propagate autonomous logics of geography and cartography. The territories of the communes foster diversity and fertility, replacing the bleak monotony of capitalist space. Reading the Invisible Committee’s description of the geography of the community, we might adopt the Zapatista slogan and call for “a world where many geographies fit”:

All that claimed to be a Commune created around them - sometimes even at a distance - a new geography. Where before there had been only regularized territories, plains where everything was exchangeable, a haze of universal equivalence, the Commune drew out a chain of mountains, with undulations, passes, summits, paths that friends passed on as amazing, and cliffs that enemies found inaccessible. All this was no longer simple, or simple in a different sense. The Commune created a political terrain that gradually expanded and branched out. In this movement, the paths it drew to other communes, the threads and connections it wove, constituted our party.

The Commune thus calls for the formation of new geographies of communism defined by various forms of collective life. Vasudevan calls alternative spaces of everyday life “expanded counter-geography, through which alternative support networks are built, friendships are forged, and solidarity is assured.” The Commune thus forms new geographies of possibility and non-capitalist relations.

Commune residents experiment with new collective spatial practices. Squatting enables self-determined practices of creative architecture and living space that promote new forms of life. As Vasudevan explains, occupying dilapidated buildings "offers squatters the potential to cultivate new forms of sociality, thereby reconciling the destructive artifacts of urban modernity with alternative expressions of human collectivity... Squatters respond to normative assumptions about life and 'home' by questioning their more fundamental spatialities." For example, squatters redesign buildings to produce expanded public spaces:

Walls were removed to increase the size of social spaces, while stairwells were created to generate a new geography of movement, now connected and held together by an inter-spatial network of doors, passages, courtyards and vestibules. These experiments in built form became a key process in exploring new micro-politics of alignment, interdependence and connection.

The construction of spaces for community life offers an opportunity to practice new forms of relationships with one another in an everyday communism of equality, autonomy and democracy. Thus, "it is the performance of architecture itself that has, in this case, become a key source of inspiration for a range of self-organizing and collective everyday practices." This collective performance transforms the participants. The collective construction of radical spaces generates what we can call a new, autonomous form of life.

In addition to architectural transformations, the interior world of the squatter communes was organized to facilitate the construction of alternative modes of existence. In a commune, life itself is structured differently: the very fact of group life force, which previously atomized humans, comes into contact with each other in everyday life. As an open letter from the Berlin Squatters’ Committee puts it, “When we occupy [a building], it is not just to protect living space. We also want to live and work together again. We want to stop the process of isolation and destruction of collective life. Who in this city does not realize the tormenting loneliness and emptiness of everyday life?”

Communes often organized themselves around collective spaces. Most important, many squatters argued, was the kitchen, which operated “as the key ‘social spatial center’ of the house.” A collectively run kitchen enabled several political interventions. First, it combated the gendered division of labor that relied on women to cook for men. Second, it linked food to community: collective meals created connections between people and with the food they ate. Finally, “outside” political life was enhanced. As one squatter put it, “When last night’s meeting was discussed over breakfast, [politics] had a completely different relationship to everyday life. Not only was the movement’s progress accelerated, but the really important issues, which were lost in the shuffle when we lived in isolation, became topics of urgency and action.” Collective kitchens are just one example of radical uses of space.

Perhaps more important to Autonomen, the squat communes functioned as spaces of cultural production. Subculture, not work, was the driving force of everyday life. As one Autonomen paper stressed, “We did not find each other in the workplace. Working in paid labor was an exception for us. We found each other through punk, the ‘scene,’ and the subcultures we entered.” Squats provided spaces for movement-controlled cultural activities. In the KuKuCK squat, for example, “fifty people lived in a complex that included three stages, performance areas for ten theater groups, practice rooms for five bands, a studio, a cafe, and a car repair shop.” Squats were also covered in beautiful art, suggesting a fertile inner self. Finally, Autonomen produced a collective identity on the street. Marching in black groups generated an exhilarating sense of comradery among accomplices and gave the movement a common identity: "The black leather jackets worn by many at demonstrations and the black flags carried by others became less an ideological anarchism than a style of dress and behavior - a lifestyle that turned contempt for the established establishment and its American 'protectors' into a virtue... Black became the color of political blankness - of withdrawal from allegiance to party, government, and nation." In a similar context, anarchist anthropologist David Graeber, in his ethnography of the North American anarchist scene, highlights the connection between punk and street action. He quotes one activist who explains:

In the Mosh Pit at a punk or hardcore show, all the kids go crazy, get together, stage dive, circle the Mosh Pit, crowd surf, asshole bouncers are twice as many as you, so you get a feel for space, fluid movement, and action. In action, use your arms to push through police lines, like forcing your way to the front of the crowd at a show with slow steady pressure. Not that all black crowds are punk rockers or vice versa, but when black crowds jumped over the heads of riot police at the Navy Memorial during George W. Bush's inauguration in 2001 to evade arrest, he was just body diving and body surfing.

3. Living Communism

"The real communist problem is not 'how to produce' but 'how to live'."

– The Invisible Committee, now

Autonomists yearn for a communist experience today, in our everyday lives, even in the bleak world of capitalism. The Invisible Committee invites us to embrace fragmentation, rather than a naive nostalgia for a world we’ve lost, and to fight on our side: “One can lament this [fragmentation] and try to swim back into the river of time, but one can also start there and see how to proceed.” Fragmentation brings with it many problems we all know all too well, including atomization, alienation, and isolation. But it also brings with it new possibilities, for “with the endless fragmentation of the world, the richness of life’s forms and its increased quality becomes dizzying—for one who thinks of the communist promise it contains.” Fragmentation leads to the possibility of living a good life in the fragments of the world we have come to inhabit and control. Indeed, “in the fragmentation there is something that points to what we call ‘communism.’” In a fragmented world, it becomes increasingly important to engage people and places. As the Invisible Committee puts it, “What we have to do, it seems, is leave home, hit the road to meet other people, to strive to make connections, whether conflicting, cautious, or joyful, in different parts of the world. What organizes us is never anything but love.” Ultimately, this means living communism now in our practices, gestures, and relationships.

Challenging traditional Marxist and anarchist conceptions of communism that focus solely on seizing the means of production, the Invisible Committee emphasizes communism in everyday life. For them, communism does not exist someday in the future; it is not simply an ideal to be fought for, but something to be lived and practiced. In fact, “the question is not to struggle for communism. The question is to live a communist life in the struggle .” This is not an anarchist pre-politics that shapes the world we hope to live in one day; rather, we must live communist lives in the conditions and struggles of today. Communism is to be practiced in our every action and relationship. “Communism does not consist in self-abandonment, but in attention to the smallest actions. It is a question of the level of our perception, and therefore of the way we act. A question of practice .” This is an affirmative response to the horrors of life under capitalism. This is why “we must care for the details of everyday life as if we were concerned for the revolution,” and why “the first duty of revolutionaries is to take care of the world they constitute.” Communism is a matter of the everyday practice of a healthy community, not just a matter of the organization of production. The goal of communism is not simply the socialization of the means of production or “a superior economic organization of society,” but “it is the great health of a way of life. This great health is obtained by patiently re-articulating the separated members of us, in contact with life.”

We should be clear, however, that owning the means of producing non-commodities—and life itself—is essential to communist life. The Invisible Committee may be too eager to distance themselves from the traditional left, so they underestimate the importance of the means of production. They do, however, recognize the importance of controlling the production of our own means of subsistence. In discussing the blockade of infrastructure, they acknowledge that “blockades are only as effective as the ability of the insurgents to supply themselves and to communicate, as effective as the self-organization of the different communes. Once everything is paralyzed, how will we feed ourselves? … Over time, acquiring the skills to provide for one’s own basic livelihood means appropriating its means of production.” But the Invisible Committee encourages building our own means of production, not confiscating the capitalist means of production. Because the problem is

Capital has taken over every detail and every dimension of existence… In doing so, it has reduced to a very small share of what one might want to reappropriate in this world. Who would want to take back nuclear power plants, Amazon warehouses, highways, advertising agencies, high-speed trains, Dassault, La Defense, auditing firms, nanotechnology, supermarkets and the toxic goods inside? … No sane person would think of that.

While the Invisible Committee may be exaggerating it, the reasoning is compelling. What would it look like to build our own infrastructure as a foundation for constructing alternative worlds?

4. Alternative infrastructure

“The revolutionary movement is not simply the result of ‘objective conditions’: it is the result of the structures we are able to build.”

– Arbeitskreis Politische Okonomie

The Invisible Council locates contemporary power in infrastructure. Power resides in the material functioning of the world, in networks of just-in-time production, and in the endless flow of goods, people, and ideas. Thus, “in the network age, governance means ensuring the interconnectivity of people, objects, and machines, and the free circulation of information generated in this way, that is, transparent and controllable.” The consequences of this are wide-ranging, but two effects are particularly relevant here. First, power’s location in infrastructure makes it vulnerable to attack. Sabotage, the blocking of infrastructure projects, and the disruption of flows immediately limit power’s ability to govern the world. Second, our ability to build our own counter-infrastructures takes on new importance. Alternative infrastructures take many forms, from collective homes and shantytowns to community gardens, women’s health clinics, and free schools. The construction of alternative infrastructures becomes itself an affirmative attack on capitalist power—or, as the Invisible Council would like to put it, the lack of power—and provides the basis for sabotage and other attacks. But perhaps most importantly, alternative infrastructures provide spaces for living in communism. They establish the conditions under which we can live differently, relate to each other in new ways, and fully inhabit our lives in relation to the earth. Yet both the Autonomen and the Invisible Council have a tense relationship with alternative institutions and infrastructures. They will be used for revolutionary purposes, but also criticized and radicalized.

Autonomen was based on the infrastructure of the alternative movement and the network of squat buildings they directly controlled. Throughout the 1970s, a network of radical spaces was established to support the movement. As one Autonomen member, known by the pseudonym Geronimo, explained, “In the beginning, many alternative projects saw themselves as everyday support structures for general political struggles: left-wing bookstores, bars, cafes, print shops, etc. Alternative activists believed in “a strong ‘utopian’ element: all these projects were supposed to provide tangible examples of a future socialist society built within capitalism. In this sense, the beginnings of the alternative movement were closely tied to the rejection of wage labor and the autonomous impulse of resistance in everyday life.” This developed into a core strategic commitment to squatting. As a group called the Proletarian Front put it, “Squatting means destroying the capitalist conspiracy in our communities. It means rejecting rent and capitalist shoebox structures. It means building communes and community centers. It means recognizing the social potential of every neighborhood. It means overcoming helplessness. In squatting and rent strikes we can find key points of anti-capitalist struggle outside the factory. Alternative infrastructure thus offers its inhabitants a new world – one based on solidarity, self-determination and equality. Many activists see it as both communism in action and the basis for the struggle against capitalism.

However, the alternative movements began to emphasize the importance of alternative infrastructures, especially as the West German working class continued to largely accept the rewards of social democracy rather than rebel. The Autonomen were clear that although they “use the infrastructure of the alternative movements… our ideas are very different from those of the alternative movements… we know that capitalism is using alternative scenarios to create new circuits of capital and labor, both to provide jobs for unemployed youth and as experimental areas for solving economic problems and calming social tensions.” Over time, alternative institutions were gradually pacified and integrated into the capitalist economy. The Invisible Committee was also critical of alternative or “solidarity” economies. In 2014, shortly after the Squares movements (the Spanish indignados, the Greek anti-austerity protests, and the US Occupy Wall Street), they wrote about the recent proliferation of cooperative networks that were inadequate responses to the desire to escape the world capitalist order and the alienation of wage labor.

At their best, cooperatives support social movements by offering concrete alternatives to traditional capitalist economic organization. However, cooperatives themselves are not a threat to capitalism, and in fact, the most successful of them tend to behave like any other capitalist enterprise. Rather than thinking in terms of production for the market economy, it is better to approach alternative economies in terms of needs, use, and complicity. The Invisible Committee states that the commune “seeks to solve the problem of needs. It seeks to break all economic dependencies and all political subjugation… The commune solves needs in order to extinguish the needs within us.” Therefore, the right direction for cooperatives is to use their equipment, hold meetings in their spaces, requisition production to meet the needs of the movement, and so on. Regardless, “the fact remains that we must organize ourselves, organize according to what we like to do, and provide ourselves with the means to do it.” Communes can also connect networks of solidarity economy and push them to replace power’s control over infrastructure.

The commune coordinates networks of cooperatives to build our capacity for autonomous existence. It is "what brings all economic communities into communication with one another, what runs through and overflows them; the bonds that hinder their self-centered tendencies." New institutions are created to suppress the institutions of capitalist state power: "The retreat from the system is never a void left behind, but an active suppression of the system. Abolition is not primarily an attack on the system, but an attack on our need for it." If used properly, alternative institutions become weapons of abolition and replace our dependence on established power with an organic dependence on each other. The liberated territory proliferates through the movement of people, ideas, and things between communes.

5. Secession, Attack, and Rebellion

"Escape, but search for weapons as you go."

– Gilles Deleuze

Instead of tending to seize and exercise power, the network of communes seeks to disengage from the grasp of power and impoverish its institutions. Secession does not mean establishing new borders, but practicing communist forms of life and promoting counter-circulation between growing archipelagos of autonomous territories.

To split is to occupy a piece of land, accept our role in the world, the way we live, the form of life, and the truth we bear, and then intervene in disputes or collusion from there . So it is to strategically connect with other opponents and strengthen exchanges with friendly areas without paying attention to any borders. Splitting... is to draw another discontinuous, archipelagic, and intensive geography.

This is how communism is built on a large scale. Territory is inhabited and controlled, and the people living within this archipelago of liberated territory build connections and material ties between them, learn to meet their needs, and build liberating relationships with each other and the land. The means of existence are appropriated and/or collectively constructed. Organic gardens and farms are established to feed people directly, free clinics are established to heal the sick, and worker cooperatives are established to meet the needs of the community rather than profit. The material construction of another world deprives capitalist state power of its ability to govern and control us. This is ultimately how the invisible committee means poverty by “becoming ungovernable.” Separation occurs not only in isolated rural communes, but in the heart of cities, small university towns, and in the connections between communes everywhere.

However, the dominant power knows its fragility and the commune cannot break away without a fight. The struggle against capitalist state power is based on communal territory. The commune is not only the center of alternative life, but also the basis for the liberated territory of attacking the state and capitalism. The attack is an affirmative component of revolutionary life. As one autonomist activist said, "Every time people begin to undermine the political, moral and technological structures of domination, an important step is taken toward a life of self-determination." Abolition attacks and suppresses capitalist state power while building a new world. The framework of the Invisible Committee is this:

The revolutionary gesture is no longer a simple violent appropriation of this world; it is divided into two parts. On the one hand, some world must be created, some form of life that is free from domination, and for this purpose what can be salvaged from the present state of things must be rescued; on the other hand, the capitalist world must be attacked, destroyed... It is obvious that if the world to be built is to be kept at a distance from capital, it can only be attacked and conspired against the latter in fact... Only affirmation has the potential to complete the work of destruction. Therefore, the gesture of abolition is both desertion and attack, both creation and destruction, all contained in the same gesture.

We must link destruction with creation, attacking the world of capitalist state power as we build our own, and protecting our own as we flee capital. This is the work of abolition.

As power resides in and operates through infrastructure, disrupting or otherwise attacking infrastructure becomes central to revolutionary political practice. Given the development of post-Fordist just-in-time production, blockades of infrastructure and circulation have become an even more potent weapon against the capitalist system. Choke points can be targeted by relatively small groups of people, whose power can be greatly increased. Circulation and logistics theorist Charmaine Chua argues that disruption and blockades of supply chains serve a dual purpose: not only do they disrupt capitalist circulation/production, but “we might also envision such events of disruption…as an ethic that reproduces alternative possibilities for communism and community from which capitalist accumulation excludes many.” In addition to disrupting already existing circulation, blockades of new infrastructure projects combine disruption with the construction of alternative worlds. Blockades are one of the primary weapons of autonomous groups. In West Germany, struggles against nuclear power plants helped form autonomous groups. In what activists call the “Free Republic of Wendland,” George Katsiaficas says, “we are ‘people’ in the fundamental sense of the word, sharing food and life outside of a monetary exchange system, creating an erotic dimension that is simply not found in normal interactions. Wendlanders live together not only to build confrontations but also to create space for self-government through political discussion.” In this way, each attack simultaneously creates a new world, and vice versa.

Building a new world while destroying the old is ultimately a question of rebellion. This does not necessarily take the form of Bolsheviks storming the Winter Palace, nor does it necessarily involve prolonged riots measured in the number of Molotovs thrown and streets liberated from the police. As the Invisible Committee puts it in The Coming Uprising , “The rise of the rebellion is nothing but the proliferation, the communication, the connection of the communes.” Liberation comes from political victory and control of space, not just through armed confrontation. “ Liberate the territory from police occupation… Armed. But do everything possible to make the use of the armed forces superfluous. In the face of force, the way to victory is politics… When power falls into the gutter, just step over it.” After the recent experience of a failed rebellion, the Invisible Committee is more cautious, warning of the growing appeal of fascism. So they conclude : “Think, attack, build – this is a brilliant line. This book is the beginning of a plan. See you soon!”

in conclusion

Autonomen were unable to rise above subcultural marginality to rise above a certain level. From a brief high point in the 1980s, when it seemed that autonomen movements had the potential to develop into a genuine revolutionary force that could challenge state and capitalist domination, they quickly collapsed in the 1990s. There are many reasons for this, including the world-changing collapse of the Soviet Union, but perhaps most importantly, the autonomen were never able to truly build lasting counter-power or mount a sustained offensive against capitalist state power. Of course, one could take a more classically Marxist stance and say that they failed because they lacked a working-class base. There is some truth in this, but it is useful to assess them on their own terms. While they could win individual battles with the police, defending squats took up a great deal of energy and resources. Most fell victim to the state’s carrot and stick strategy, which offered favorable leases to squatters who agreed to legal regularization and ruthlessly attacked those who resisted with ruthless force. The autonomen were never able to move beyond a strategic equilibrium into meaningful separation and powerlessness. Indeed, defending the police or rioting in the streets does not endow the police with power as a state institution. So what is needed to overcome this form of state power?

The Invisible Committee is motivated in large part by a desire to understand the failures of autonomous movements and to correct their mistakes. As such, they focus not only on living communism but also on thinking seriously about the nature and forms of contemporary power and how to attack and neutralize it. Their answers lie in blockades, separations, and impoverishment. In the wake of the 2011-2012 Square Movement, many recent outbreaks have taken these forms, from the Notre-Dame-des-Landes ZAD (Zone for Defence: an autonomous zone that successfully blocked the construction of a French airport, one of a dozen ZADs across the country) to the Olympia rail blockade and the Occupy ICE actions across the US over the years. After their latest work, the Invisible Committee has remained largely silent, choosing instead to immerse themselves in on-the-ground political work within the ZADs. New innovations, as always, will come from the struggles themselves.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!