BISHOP KALLISTOS WARE: Saint Nicodemus and Eros (4) Translated by Yuan Yongjia

This article is translated from: Ware, Kallistos. “St. Nikodimos and the Philokalia.” In The Philokalia : A Classic Text of Orthodox Spirituality , edited by Brock Bingaman, Bradley Nassif, and Inc ebrary, 9–35. New York: Oxford University Press , 2012.

This is the fourth part.

Note:

- This article is an academic article on "Eros Collection" by Bishop Kallistos Ware, a well-known Orthodox scholar, Bishop Kallistos Ware. The author refers to his views when writing the "Eros Collection" series. The author thought that this article had high academic value and was a must-read for the study of Eros, so I translated it into Chinese. All names and places are in English, and the annotations are not translated, in order to facilitate the follow-up of pictures. For the convenience of your reference, I have marked the original page number in the turn of the page, in the format: (page number). Enjoy!

- The footnotes of each published article start from 1. If you see how many footnotes you see, you need to start counting from the footnotes of the first translation, and then count up from the second article to find the footnotes.

- If the translator wants to add a note: it will be marked with the word "press" in brackets, that is (press: ...)

- Copyright statement: If any media or self-media considers reprinting the content of "Eastern Church", please check and reflect on the work as much as possible, and then reply through the website platform, or contact via email (areopagusworkshop@gmail.com).

Be a Monk, Not a Visionary: The Inner Consistency of Eros

Having investigated some of the factors that may have influenced the editing work of Macario and Nicodemus, let us now try to identify the main features of the spiritual teaching contained in Eros. Are there certain recurring themes in the book that have a real unity, rather than a pile of disparate documents? To find this internal consistency, we asked three questions: What does the readership look like to editors? What is the scope and content of this work? How does it envision the supreme goal of spiritual pursuit? Previously, we've been looking at Eros from the outside; now let's look at it from the inside.

1. Readership

Here, the editors of "Eros Collection" insist on two things, at first glance: at least it is full of tension, if not contradictory. On the one hand, they contain a lot of texts: it is extremely important to emphasize the guidance of experienced teachers. On the other hand, they say that Eros is a book for all Orthodox Christians, monks or married, clergy or lay people. How to reconcile the two? Many Orthodox Christians who might read Eros have no spiritual teacher to instruct them. In this case, is it safe for them (25) to study Eros? Could the contents of these Eros Books be misused if they were published in print?

(Translator's note: Divine Master, Spiritual director, spiritual father or mother in English, specifically refers to the spiritual teacher who is responsible for the spiritual growth of people. Just as various skills, such as carpenter, foreman, electrician, mathematics, physics, etc. need to find a master Just like learning it well, spiritual practice, the highest of science and art, requires an experienced teacher, which the Eastern Church calls a spiritual teacher.)

Regarding the first point, the need to obey the priest is the theme of the entire Eros. St. Theodore of Edessa (7th-9th centuries) said: "When you live with a priest who helps you. Let no one take you away from love and Live with him separately. Even if he rebukes or beats you, never judge him, reproach him, listen to his slanderers, and be not with his critics. [1] ” New theologian Simon affirms : "A person of pure faith will leave everything to the divine teacher, as if in the hands of God. Even if you are thirsty, don't ask for water until your divine teacher actively persuades you to drink water" [2] . The monk Nikiphoros, speaking of the gift of concentration, also emphasizes:

"Focus" is imparted to the vast majority of people, or even almost everyone, through the method of master-apprentice teaching. For it is rare to receive this gift directly from God through diligent effort and fervent faith alone without being taught, and this very few direct means of attaining this gift cannot be the standard method of attaining concentration. Therefore, it is necessary to find the right mentor...if there is no such mentor, you must be diligent in finding one. [3]

So what do those who fail to find the right mentor do? Nick Furrow's advice: In the absence of guidance from a spiritual teacher, they should employ a special physical technique when reciting the Jesus Prayer, including breathing control and focusing the mind on the position of the heart. Most orthodox teachers today, however, believe that this technique—while itself theologically defensible—could have serious negative consequences for our physical and mental health if misused. Therefore, contrary to Nick Furrow's advice, they suggest that this technique should only be used when a person is under the direct direction of an experienced elder. [4]

Another possibility is to read books like Eros, but the difficulty is: the general advice in the written text doesn't always apply to everyone's specific situation. How can I know that the directions in the printed book apply to me personally without the advice of a spiritual teacher? It is for this reason that for a long time Pais Velichkovsky was reluctant to have his Slavic translations published in print, preferring that they be circulated only in manuscript form. In this way, he hoped, they would be delivered to those who were ready in the eyes of the divine, and published in print for all to use. Regarding this, he wrote to his friend Archimandrite Theodosy, saying,

I am both delighted and terrified of the print publication of the Greek and Slavic Godfather books. Happy that they will not be forgotten and that they can be more easily obtained by lovers of the godfather; but also fearful that they may be sold like other books, not only to monks, but to all Orthodox Christians (26). The latter, without the guidance of a spiritual teacher, may selfishly study the work of inner prayer and thus fall into self-deception. The books of the godfathers, especially those concerning true obedience, an alert mind and stillness, heedfulness, and mental prayer performed with the mind in the heart, apply only to the seminary, not to the whole Orthodox. [5]

Under pressure from the Archbishop of St. Petersburg, Gabriel, Pais finally reluctantly agreed to allow Dobrotolubiye to be printed.

However, Nicodemus adopted a different methodology. In his preface to Eros, he acknowledged the problem: "As we write here, there may be a reminder that you are making the contents of these books public, making these secrets public, and being heard by outsiders. It is not right, because they will say that it is dangerous for some people (press: referring to people with ulterior motives)." [6] (Note: the author has translated directly from Greek here, so it is different from the English version)

Despite the profound significance of the priest's personal instructions, Nicodemus prepared to publish the Eros in print. In his view, the potential benefits far outweigh the possible risks. He admits that "occasionally someone goes astray" but many others, if they begin their inner prayer "with humility and mourning," will benefit greatly from this book. [7] Nicodemus concluded that if we lack a teacher to guide us, let us entrust ourselves to the Holy Spirit; for he is fundamentally the only teacher.

This preference of Nicodemus is obvious: by far the best approach is to diligently and persistently seek out a spiritual teacher who can give us personalized guidance. Such a teacher, based on his discernment of our specific spiritual state, at each point in our journey will advise us which parts of the Eros, which parts to read, which to pay attention to, and which to ignore for now. But if it wasn't for hesitation that we didn't find the Master, that doesn't mean we should put the book aside and conclude that it's not a good read. Let us pray for the gift of God as we read, He will guide us into all truth.

In the early 1950s, Father Nikon of Karoulia blessed Gerald Palmer and Evgeniya Kadloubovsky with the publication of In the English translation of Eros, he held the same views as Nicodemus. Father Nikon is well aware that many readers of the English translation will be non-Orthodox, even non-Christians, so there is a risk. But, like Macario and Nicodemus, when they sent the manuscript of the Greek Eros to a printer in Venice, he thought the risk was worth taking.

2. Scope and content

A basic and intentional limitation in Eros is obvious. This work is not concerned with external ascetic practices but with inner prayer. Authors provide only occasional guidance on things such as fasting rules, sleep time, or the number of times to kneel during prayer. Similarly, there is very little about the reading of prayers (divine office, press: more refers to the recitation of specific prayers at specific times each day) or liturgy. The meaning of the sacrament and other sacraments is internalized. The focus of attention is not (27) on external ordinances, but on internal protection of the mind (intellect nous ), the battle against lust and evil thoughts (thoughts logismoi ), and how to gain vigilance (vigilance) and meditation. In conclusion, as Nicodemus emphasizes in his preface, the work involves the kingdom of our hearts (Luke 17:21) and the discovery of our inner self, made in the image of God (Romans 7:21). 22; 2 Cor. 4:16; Eph. 3:16).

(Note: Many scholars and believers translate Intellect, the Greek word νους as intellect, spirituality or intellect, but in the spiritual tradition, the word is mainly used for communion with God. The translation as intellect or intellect emphasizes that The acquisition of spiritual knowledge in communion with the Lord is one of the traditions introduced by Elvagrei, which was later corrected by the Confessor Maxim's "The Four Hundred Laws of Love", that the essence of spirituality is to be in love with each other. Communion with the Lord. The author took Maxim's understanding and decided to translate νους as mind, or mind, and according to the context, it will also be translated as mind, to emphasize that communion with God is spiritual, because God is a spirit)

At the same time, in the "Love God Collection", the inner prayer and the sacrament cannot be viewed separately. Even if the sacraments are internalized, that doesn't mean they are undervalued. The significance of baptism and communion in penance and mystical life is particularly evident in the Century of Kallistos and Ignatios Xanthopoulos at the end of the fourteenth century. In the essay, the author begins by asserting that the foundation of all Christian life is the grace of baptism, which is personal and inalienable to each of us. Our end is in the beginning: the goal of the spiritual journey, they say, is "to return to that perfect spiritual re-creation and renewing of grace, which was given to us free from the heights in the holy pool in the beginning." [8 ] After discussing at length the battle against lust and how to live the Jesus Prayer, Callisto turns to the sacrament. Before the Konivatis conflict, they suggested "continuous communion," which, if possible, meant daily communion. [9]

As in the Eros, the prayer of the heart and the sacraments cannot be separated, nor the spirituality and the doctrine. Although there are no strictly doctrinal writings in the Eros, the teachings on evil thoughts and virtues, the calling of the holy name, and the prayer of the heart are often placed in theological contexts, in parallel with the teachings of the Trinity, creation and the Fall, and the passage of Christ Salvation: the incarnation, the mountain in disguise, the crucifixion, the resurrection and the second coming. In this way, "Eros" meets Vladimir Lossky's standards.

Far from opposing each other, theology and mysticism support and complement each other. The two are interdependent...Therefore, there is no Christian mysticism without theology; but above all, there is no theology without mysticism...Mysticism is...the fullness and crown of all theology; it is the most transcendent theology. [10]

The authors of "Eros" belong to Eastern Christianity. The only exception is St. John Cassian (c. 360-430), a notable exception because although he lived in the south of France in his later years and wrote in Latin, in his formative years he lived in Egypt and he 's writings reflect the views of the Desert Godfather, especially his teacher Elvagre. On other occasions, Nicodemus made adaptations of Roman Catholic writings, while in Eros, he and Macario strictly adhered to the devotional traditions of the Orthodox Church.

While there is nothing Western or Roman Catholic in the Eros, there is also nothing anti-Western or anti-Catholic. In The Rudder Nicodemus writes polemically against the Church of Rome, but throughout the Eros, he does not do so. There is of course a reason for this, and the Catholic censors of the University of Padua, in their license or authorization at the end of the 1782 edition of the Eros, were willing (28) to certify that the book did not contain any "infringement of the Catholic Faith (Santa Fede Cattolica)". Content. [11] A Catholic reader today would certainly agree with this assessment, unless he or she happens to be a staunch anti-Parama (fortunately, most Catholics today are not).

In Eastern Christian spirituality, the texts in Eros mainly reflect a particular path: the Evagrian-Maximian path. This can be seen in the works not included in the book. There is nothing from Irenaeus in the Eros, but this exclusion is not surprising since he was largely forgotten in the Byzantine and post-Byzantine East in general. More importantly, Athanasius, Basil, Gregory of Nathion, and Gregory of Nyssa are not included; likewise, Apophthegmata, Barsanouphios , Dorotheos, and the Syrian Ephron Greek translations are not included, and there is no work by Dionysius. There are some selected sermons from Makarian, in Symeon Metaphrastis' version, but they are relatively short.

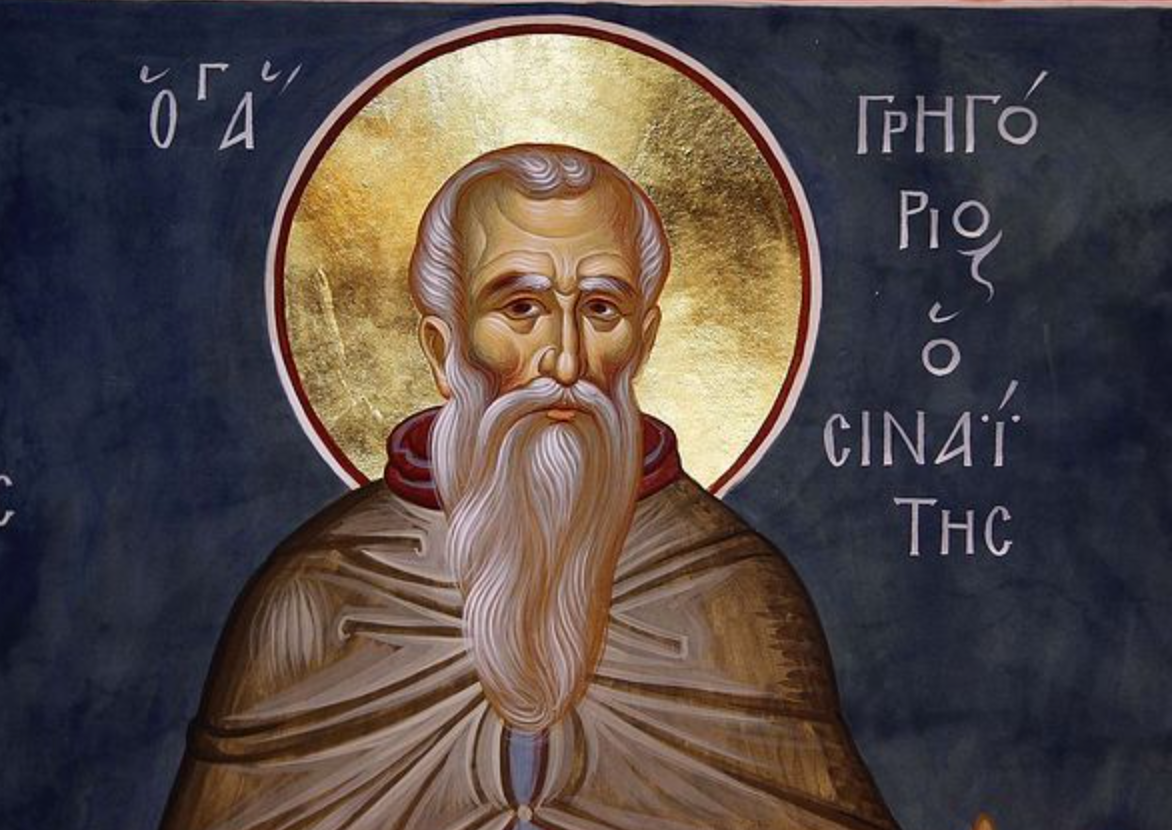

We thought there were practical reasons for these omissions. But its cumulative effect is to ensure that the Evagrian-Maximian spiritual path prevails in most of the Eros. Although only a few pages are devoted to Elvagrei's own work, his classification of the three stages of the spiritual path is used throughout the book: practicing virtue ( praktiki ), contemplating nature ( physiki ), and contemplating God ( theologia ). [12] Elvagra's description of prayer is repeated in many places in the book: shedding of thoughts, a laying-aside of images and iscursive thinking. "When you pray, don't form any sacred image in your heart, and don't let any image be imprinted on your mind, but approach the invisible God in an invisible way, and then it will become clear," said Elvagra. [13] This is an interpretation of prayer, e.g., Diadochos, Hesychios, Peter of Damascus, Gregory of Sinai, and Caris Kallistos and Ignatios Xanthopoulos. True, there are occasional passages in the Eros that suggest imaginative musings on the life of Christ, and especially his passions. An obvious example is found in the Letter to Nicolas by the ascetic Marco (alias, Friar Marco). [14] In general, however, the style of prayer advocated by the Eros, especially in relation to the Jesus Prayer, is the "formless" or "negative" prayer taught by Elvagra.

Three main themes unite the teachings of Inner Prayer in Eros

1. Awake ( Nepsis ). The centrality of this quality can be seen in the name Nicodemus and Macario gave to their work: Philokalia ton Ieron Neptikon (The Book of Eros by the Godfather of Divine Alertness). Nepsis is a key concept in Eastern Christian spirituality, meaning inner sobriety, clarity, vigilance, sobriety, lucidity, alertness, watchfulness and vigilance. At the beginning of On Watchfulness and Holiness, Haskell links watchfulness to a series of basic themes: with concentration (prosochi), purifying the mind, guarding the mind, the Jesus prayer, stillness, and contemplation (comtemplation) [15] . Nicodemus, in his preface, accurately sees vigilance as all-encompassing. [16]

2. Retreat ( Hesychia ). Among Hesco's associations of vigilance with other themes, none is more important than meditation, that is, stillness or silence of the heart [17] (29) This is the second theme in Eros. Its meaning is not so much the silence of the body as the silence of the mind, not so much the silence of the tongue as the freedom of the mind from images and concepts. As expressed by Gregory of Sinai, who adapted the above-mentioned quote of Alvargren: "Retreat is the sheding of thoughts" [18] Therefore, meditation is the nakedness of the mind, the less A form of noetic poverty. A yogi is one who strives to progress from a multitude of rambling thoughts to pure contemplation in silence. In the words of Sinai's Gregory: "Keep your mind away from colours, forms and shapes". [19] Elsewhere he writes: "Let us seek to possess only the energies inherent in the mind in a completely formless manner." [20] He concludes: "Be a monk, not a visionary." [21] By saying this, the authors of Eros do not mean to belittle or deny the liturgical prayers that are rich in symbolic imagery. They take it for granted that believers read the Bible, memorize the Psalms, and participate in the sacramental life of the church. What they wanted to do was to draw attention to the fact that, alongside liturgical worship, there was another way of praying that went beyond visual imagination and brain reasoning. Elvagra described prayer as the shedding of evil thoughts, but neither he nor anyone else ever intended to see it as the definition of prayer in all its forms.

(Press: thoughts literally translated as thoughts, thoughts, but in the context of "Eros Collection", in most cases it refers to evil thoughts containing lust)

3. 3. Jesus Prayer. According to the Eros, the state of vigilance and meditation is attained by remembrance ( mnimi ) and invocation ( epclesis ) of the holy name of Jesus. As emphasized by fourteenth-century authors, the Jesus Prayer brings the heart ( nous ) into the heart ( kardia ), thereby bringing about the union of the two [22] . The Book of Eros has always emphasized two points of the Jesus Prayer: the call to the Holy Name should be as continuous as possible, because its purpose is precisely to help us "pray without ceasing" (1 Thess. 5:17); it should also be As much as possible without images and rambling thoughts, as it is also intended to start us in a state of meditation.

Among the various writings in Eros, some suggest the use of a bodily technique in the Jesus Prayer, especially the control of breathing [23] . These passages are particularly emphasized by some Western scholars, some of whom consider it a kind of "Byzantine Yoga". However, when these passages are read in the context of the entire Eros, it turns out that body skills are nothing more than an optional option, helpful for some people, but by no means essential . It is far from constituting the essence of the Jesus Prayer, as it can be practiced in its entirety without the use of any physical technique. In the practice of the Jesus Prayer, what is really necessary is faith and love to call upon the Holy Name; everything else is secondary.

While the text in the Eros Books associates the recitation of Jesus' prayers with the rhythm of breathing, there is nowhere to suggest that the prayers should be in harmony with the beating of the heart; and most Orthodox teachers consider the practice very dangerous. Surprisingly, nowhere in Eros is mentioned (30) the use of prayer ropes (Greek: komvoschoinion ; Slavic: tchotki ) in conjunction with prayer. The use of prayer beads, regardless of form, is certainly ancient and widely used, and can be found in both non-Christian and Christian; however, how it was adopted in Eastern Christianity is vague and requires further study [24] . Of course, as can be seen from the icons of the monastery, prayer ropes have been commonly used in the Orthodox Church since the seventeenth century.

Calling on the Holy Name is undoubtedly the basic theme of Eros, but to make it a practical manual on Jesus' prayers and nothing else would be a fatal mistake. Some of the "Little Love Gods" published in the West may be misleading about the general character of the book because of their one-sided focus on Jesus' prayers. In fact, in the first three volumes, there is almost no mention of the Jesus Prayer, except for Hesychios, Diadochos, and Abba Philimon. The two most extensive authors of the Eros, Maximus the Endured and Peter of Damascus (12th century), make no mention of the Jesus Prayer at all. It is only in the last two volumes that the invocation of the Holy Name begins to take center stage, and even here most of the space is devoted to other topics.

So, when reading Eros, it is clear that the editors are concerned with placing the calling on the Holy Name in the broader context of penance and contemplation. They don't see the Jesus Prayer as just a devotional "skill" that can be practiced separately from the overall Christian life. However, while the spirituality of the Eros cannot be simply reduced to the recitation of Jesus' prayers, the practice of prayer does constitute an important unifying thread in the complex tapestry of the Eros.

[1] "A Century of Spiritual Texts" 40: Philokalia 1, 310; ET 2, 21.

[2] “Practical and Theological Texts” 16–17: Philokalia 3, 239; ET 4, 28.

[3] "'On Watchfulness and Guarding of the Heart": Philokalia 4, 26–27; ET 4, 205.

[4] See K. Ware, “Praying with the body: the hesychast method and non-Christian parallels,” Sobornost incorporating Eastern Churches Review 14.2 (1992), pp. 6–35; note especially the strictures of St. Ignaty Brianchaninov and St. Theophan the Recluse, p. 22.

[5] Rose, Blessed Paisius Velichkovsky , pp. 191–92; cf Tachios, O Paisios Velitskophsky , pp. 113–14.

[6] Philokalia 1, xxiii.

[7] Philokalia 1, xxiii–iv.

[8] “Century” 4: Philokalia 4, 199; ET Kadloubovsky and Palmer, Writings from the Philokalia on Prayer of the Heart, p. 166. For similar teaching on the recovery of baptismal grace, see Gregory of Sinai, “On the Signs of Grace and Delusion” 1–3: Philokalia 4, 66–69; ET 4, 257–59. Nikodimos also speaks of the reactivation of baptismal grace in his introduction: Philokalia 1, xx. On the sacramental teaching of the Xanthopouloi, See K. Ware, A Fourteenth-Century Manual of Hesychast Prayer: The Century of St. Kallistos and St. Ignatios Xanthopoulos (Toronto, Canadian Institute of Balkan Studies, 1995), pp. 29–32.

[9] “Century” 91–92: Philokalia 4, 284–89; ET Writings, pp. 259–64.

[10] The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (London, 1957), pp. 8–9.

[11] Philokalia (Venice, 1782), p. 1207. For obvious reasons, this licenza does not appear in the later editions of the Philokalia published in Athens.

[12] The title page of the Philokalia refers not only to the threefold Evagrian scheme but also to the somewhat different triadic pattern put forward in the Dionysian writings: purification (katharismos), illumination (photismos), and perfection (teleiosis). Within the Philokalia itself the two schemes are sometimes combined, for example, by Nikitas Stithatos (eleventh century). But in general it is the Evagrian terminology that predominates.

[13] “On Prayer” 67, 71: Philokalia 1, 182; ET 1, 63–64.

[14] Philokalia 1, 134–35; ET 1, 155–56; ed. G.- M. de Durand, Sources chrétiennes 455 (Paris, 2000), pp. 134–40. Fr. de Durand questions the Marcan authorship of the Letter to Nicolas, in my view on insufficient grounds.

[15] “On Watchfulness and Holiness” 1–6: Philokalia 1, 141–42; ET 1, 162–63.

[16] Philokalia 1, xx.

[17] “On Watchfulness and Holiness” 5: Philokalia 1, 142; ET 1, 163.

[18] “On Prayer” 5: Philokalia 4, 82; ET 4, 278; citing St. John Klimakos, Ladder of Divine Ascent 27 (PG 88.1112A); cf. Evagrios, “On Prayer” 71 (n. 75) .

[19] “On Prayer” 7: Philokalia 4, 85–86; ET 4, 283.

[20] "On the Signs of Grace and Delusion" 3: Philokalia 4, 68; ET 4, 259.

[21] “On Prayer” 7: Philokalia 4, 85; ET 4, 283; cf. “On Commandments and Doctrines” 118: Philokalia 4, 53; ET 4, 240. A “phantast” is one who depends on the phantasia or imagination.

[22] On the meaning of the terms nous and kardia, see K. Ware, “Prayer in Evagrius of Pontus and the Macarian Homilies.” in R. Waller and B. Ward (eds.). An Introduction to Christian Spirituality (London , 1999), pp. 14–30. For further bibliography on the Jesus Prayer, see K. Ware, “The Beginnings of the Jesus Prayer,” in B. Ward and R. Waller (eds.), Joy of Heaven: Springs of Christian Spirituality (London, 2003), pp. 1–29.

[23] See above, n. 66. See K. Ware, “Praying with the body: the hesychast method and non-Christian parallels,” Sobornost incorporating Eastern Churches Review 14.2 (1992), pp. 6–35; note especially the strictures of St. Ignaty Brianchaninov and St. Theophan the Recluse, p. 22.

[24] The book of E. Wilkins, The Rose-Garden Game: The Symbolic Background to the European Prayer-Beads (London, 1969), does not shed much light on this matter.

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More