傻瓜的血脉使然

Two Globalizations, Two Conceptions of International Orders

one

In 1986, the historian of international relations, John Gaddis, in his article "The Long Peace", pointed out that the period from 1945 to that time was an unprecedented period of peace in human history (his main evidence is that during this period, various It is rare that there has been no direct conflict between major powers). Other researchers have tested his claim with more quantitative data, and the general conclusion is that the "Long Peace" does exist. For example, in the 1950s, there were an average of 6 to 7 international conflicts per year around the world, and in the 21st century, this number has dropped to less than one. The number of war-related deaths per million people fell from 240 in 1950 to 10 in 2000. In addition, both the average duration of wars and the extent to which wars endanger the nation's survival have declined significantly (Kalevi J. Holsti, 1991). It is precisely because of this remarkable decline in international violence that Stephen Pinker optimistically wrote "The Good Angels in Human Nature", describing it as part of an ultra-long-term trend in human history.

Whether or not this ultra-long-term trend really exists, we can at least say with confidence that the post-World War II world was indeed a more peaceful, less violent state-to-state world, based on data from the past two centuries.

Interestingly, this trend happened right in the midst of two globalization turns. Here, we need to first introduce the two stages of globalization - regardless of pre-modern globalization, it is generally believed that the process of globalization since modern times can basically be divided into two stages. From the beginning of the revolution (early 19th century) to World War I, World War II (a stranded world between World War I and World War II), the latter globalization restarted after World War II.

There is no doubt about the strength of the latter globalization, but the former globalization is not far behind. "The world is a city" may remind you of Thomas Friedman's "The world is flat" assertion, but it was uttered by Baron Rothschild in 1875.

According to estimates, by the eve of the First World War, the total value of world exports had accounted for 16% to 17% of the world's total income. Among them, Britain's exports accounted for almost 60% of its GDP. In addition, both the speed of information dissemination (the emergence of transnational cable and telephone systems) and the scale of human movement (statistically, there were 50 million international migrants across the Atlantic between 1850 and 1914. According to the 1900 census, 14% of Americans were born abroad, compared with 8% in 2000), both in unprecedented growth. Note that during the four decades from 1870 to 1913, there were almost no economic restrictions on cross-border economic transactions (for example, until 1879, 95% of German imports were still tax-free), a person traveling from a country to To go to another country, there is almost no need for a passport. By some measures, the globalization process in the 19th century was stronger than that in the 20th century. A report by the International Monetary Fund in 1997 pointed out that at that time, the share of capital flows in economic output was still far below the level of the 1880s.

Because of this, some economists do not see contemporary globalization as unprecedented, but as a kind of reconstruction or even catch-up (Zevin, 1992; Sachs and Warner, 1995; Rodrik 1998). In a 1999 article, Kirsten concluded: "Perhaps the greatest myth about globalization is that it is new. In a way, its zenith occurred a century ago. The 20th century in economic history The main reason it’s memorable is its retreat from globalization. In some ways, it’s only now that the world economy is roughly as interconnected as it was more than a century ago.”

two

Here, I am not saying that the emergence of the "Long Peace" has any causal relationship with the transition between old and new globalization. However, there is a correlation between them. I will explain this below.

The former globalization took place in a more volatile and conflicting international political order. In the eyes of many people in this era, chaos, conflict and progress and prosperity seem to go hand in hand, and they have an unusually positive view of war. The mainstream ideology at the time seemed to be invariably not taking international conflict as a serious matter. For example, liberals generally believe that competition is beneficial to society, it is the driving force of social progress, and the competitive nature of human beings is regulated by natural laws and regulations. It applies to both domestic and international societies; conservatives of that era believed that struggle was an inevitable feature and consequence of relations between individuals and nations, and that international conflicts could be seen as balance of power politics The natural manifestation is a means of automatic adjustment of the balance of power in the international system (in the last century, Edmund Burke attributed European civilization to the existence of a balance-of-power system that ensures a state of pluralistic competition among countries); as for radicals, such as Marx and Engels regarded struggle as an inevitable stage of historical movement.

By the mid-to-late nineteenth century, with the rise of nationalism and social Darwinism, people had more rose-colored imaginations of war and international conflict. They think that war is like wildfire in the forest, which burns away the branches and leaves the trees (nations) healthier. For example, Conan Doyle sighed through the mouth of Sherlock Holmes in his works: "It will be cold and bitter, Watson, ... but, after all, it is God's wind, and after the storm has passed, there will be a patch in the sun. A cleaner, better, and more solid earth.” (It should be pointed out here that people at that time were very strong, and believed that the strong were the vanguard of civilization, which was one of the ideological cornerstones of imperialism).

If we put aside some of the assumptions contained in these ideologies and examine them in the history of the nineteenth century, we will find that the reason why people at that time believed in the above point of view was precisely because it was to some extent is indeed historically true.

The nineteenth-century world was in a state of low-intensity competition relative to the violence of the early twentieth century and the mild years of the mid-twentieth century onwards. And it is this state that has led to liberal reforms across Europe (in harsher times, countries have no time to undertake such reforms, and in more moderate times, governments have no incentive to reform without survival pressure). We can see a pattern repeated over and over in nineteenth-century European history: after a war, feudal privileges were abolished and individual rights were granted. Serfdom in Prussia was abolished after the disastrous defeat at Jena (by the way, Hegel wrote a book devoted to this battle, calling it "The End of History"), and the liberal reforms in Austria started from It began after the defeat of the Italian War in 1859, and the great loosening of the Russian autocracy also originated from the tragic experience of the Russian army in the Crimean War.

In fact, not only European countries were like this. At that time, all countries that were aspiring to self-improvement had to take free reform as their task. In order to compete with the nations, it is necessary to give up the power of the people. At the time of the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese Senate wrote in the "Restoration for Promoting the National Constitution" (1878): "(Today's world) is famous for its enlightened and prosperous countries all adopt constitutional government... If the civil rights are not asserted, the country will fall apart, so The monarch cannot enjoy his power alone. Therefore, if you want to share the power of the monarch and the people, so that the power of the monarch and the people can have their proper place, it is necessary to formulate a national constitution." A group of old warriors can have such a vision and idea, and it cannot but be attributed to the kind of that time. The strong influence of "world trends".

Therefore, the prevailing conception of the international order at that time was as follows: within the country, implement economic freedom and a constitutional system, and in international relations, conduct free trade and balance of power/power politics. The two promote each other, promote reform through conflict, and feed back the competitiveness of countries through reform.

The outbreak of the First World War ended the process of globalization at that time, triggering a great ebb tide towards localization, which has since shattered people's confidence in this conception of an international order. People realize that the combination of free trade, constitutional systems, and great-power balance-of-power politics is not enough to provide a stable scaffold for the international order. Competition among the great powers, if unchecked, would be disastrous. So something has to change.

three

From this perspective, the Wilsonianism that emerged after the First World War and the hegemonic multilateralism system that emerged after the Second World War are all patches to the original conception of the order. If the previous international order was of the so-called "laissez-faire" type, then the subsequent international order has some meaning of "legal control". For example, Wilson believes that imperialism is the cause of the war, then decolonization and the creation of nation-states around the world are natural; another example is many international institutions, such as NATO, the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and The WTO, etc., began to become one of the protagonists in international politics. Regarding these, Keohane and other state relations scholars have already described a lot, so I won't repeat them here.

These measures have indeed played a role in appeasement (Great Pacification) to a large extent (of course, the balance of nuclear terror also has its role, but this can only explain that there is no war between big powers, big powers and small powers, and small powers and small powers. Peace between small nations cannot be explained by it). In his research on the causes of contemporary wars, Kalevi Holsti pointed out that between 1945 and 1989, the number of wars that broke out because of territorial issues decreased by nearly 50% compared with 1815-1941, and the number of wars caused by business or resources decreased by nearly 50%. Dispute-induced conflicts declined more (abstract issues—such as national self-determination, ideological disputes, and support for kinship—became an increasingly important source of international conflict). In other words, the major factors that traditionally trigger international conflicts are being eliminated. After the Cold War, this situation became more apparent, so much so that John Keegan said in his famous book "History of War": "I have spent my life reading war history, hanging out with veterans, visiting old battlefields, and observing the effects of war. After that, it seemed to me that the war was about to die out, and whether it was rational or not, at least it was probably no longer a necessary and effective means of dealing with differences.” (Keegan, 1993)

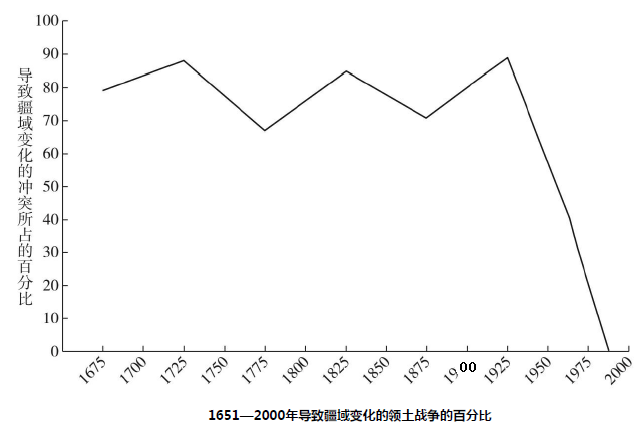

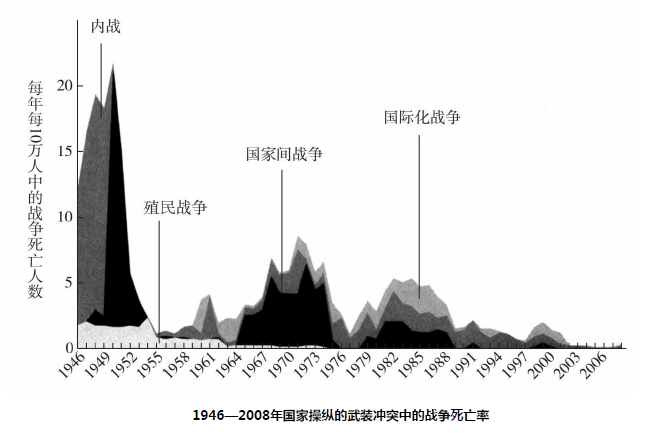

This trend is shown in the following two figures:

Note: Both pictures are quoted from Pinker's "Good Angels in Human Nature"

It is precisely because the security of various countries has been guaranteed that the threat caused by anarchy in international relations has decreased. This is the basis of order on which current globalization depends. The sword is turned into a plow, and various international systems are infiltrated into countries. , forming a more homogeneous interface, the security of various transactions is also guaranteed, and the global financial, capital, technology and commodity markets are prosperous.

However, globalization under this international order is not without weaknesses and flaws. Bruno de Mesquita mentions in the Dictator's Handbook the phenomenon that the international community's social relief and funding programs for certain countries actually delay the necessary political and economic reforms in that country. It's because the governments of these countries can draw resources from aid to maintain systemic governance. Mesquita gave an example - the UN Security Council has 10 non-permanent members, and it was found that the economic growth rate of non-permanent members over a two-year term was, on average, 1.2 percentage points lower than that of other countries that were not elected. . This is because non-permanent members are more likely to receive international aid and thus less sensitive to efficient social and economic governance (Mesquita, 2011).

If we extend this logic, we may also find another similar phenomenon: the existence of transnational capital, commodity and technology markets allows also to reduce the incentive for some countries to carry out internal reforms - if a country is export-oriented, its main Economic resources can be obtained from outside, and the protection of trade property rights mainly relies on international justice, so the country is also similar to obtain some kind of international assistance, which may cause the government of this country to ignore domestic system construction. This is most evident in oil-exporting countries. In other words, this globalization produces parasitic regimes whose existence depends on passing on their institutional costs to the international community.

Perhaps the worst flaws are psychosocial. Since the territorial and sovereign integrity of basically every country can now be more effectively guaranteed, many countries fundamentally lack the pressure to survive, and the sense of urgency for change no longer exists. The worldwide ebb of democratization since 2000 may be seen as a footnote to this deficiency. Without real reforms in individual countries, globalization risks subverting itself. This is because within such a country the costs/benefits of globalization are likely to be unevenly distributed, thereby stimulating an anti-globalization movement.

Four

In short, there have been two kinds of globalization in the world since the nineteenth century, based on two different conceptions of international order, one more violent and one more peaceful, the violent hides the seeds of destruction, the peaceful. that slows down the possibility of change.

We can see that, up to now, globalization seems to be entering a stage of ebb. The signs here are that in the past decade, the ratio of global trade to GDP has stagnated or even regressed, and multiple regional cooperation mechanisms have emerged. Fissures (such as Brexit, or the US back and forth on multiple regional cooperation agreements), not to mention the huge blow to the global market caused by the new crown epidemic (so that the BBC asked on the program "Will the new crown end globalization?" such a problem). A lot of people feel quite sorry for this ebb, but I would say that if this ebb can bring more competition at the national or regional level at the international level, then maybe it has its benefits. A return to the nineteenth-century state of free competition among great powers is certainly dangerous, but it is clear that today's globalization should also be patched.

Note: This article has been published in The Surge: The Market for Ideas.

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…