数学本科、统计硕士、历史博士。怀疑论患者。公众号&豆瓣:窃书者。

Destiny is mine: the rational basis behind superstitious behavior

Yesterday, a friend complained to me that my parents posted a lot of spells to worship all day because of the epidemic. He was very angry: "This kind of obvious superstition, they don't listen to what I say, and they can't communicate at all." I said, superstition is often two sides. The categories of thinking are different, and there are not necessarily no rational factors in them. I once wrote an article defending "superstition" with probability and statistics: Many superstitious activities actually have a solid rational basis.

Hume once asserted in "Studies on Human Understanding": "No evidence is sufficient to establish a miracle unless its 'falsehood' is more miraculous than the fact it is intended to establish; but even in this case, The two arguments can still cancel each other out, and the stronger argument can give us only as much conviction as the weaker one has been reduced."

That no testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous, than the fact, which it endeavours to establish; and even in that case there is a mutual destruction of arguments, and the superior only gives us an assurance suitable to that degree of force, which remains, after deducting the inferior.

This passage puts it bluntly from a probabilistic perspective, that people should not believe in so-called miracles unless they believe that the miracle (without the help of God) is less likely to happen by chance than the probability that God exists .

This article is divided into three parts. The first part is based on Bayesian statistics, which is equivalent to interpreting Hume's point of view in reverse, that is: since many people believe in miracles, it means that their estimate of the probability of the existence of God x is not lower than The random probability y of those miracles. (It can then be deduced that although x varies from person to person, there is likely to be an appreciable lower bound.) So what small, improbable event would witnessing a significant increase in the observer's confidence in supernatural powers? What is the proportional relationship between x and y? (Friends who are not interested in mathematics can skip it)

The second part discusses cognitive issues. One is that people's perception of numbers has the smallest unit, so that in the face of extremely large numbers or extremely small probability events that exceed the limits of perception, people cannot accurately distinguish and conceptualize them. (In layman's terms, most people can't express the difference between one-in-a-hundred and one-in-a-million beauties, although the latter is literally a hundred times more difficult than the former) This leads people to "not so small" because of random probability. ” events and reject probabilistic explanations in favor of belief in supernatural powers. The second is why people tend to use different probability distributions to look at low-probability events that happen to themselves and others.

The third part uses the conclusions of the first two parts and applies them to the historical field. It is used to explain the cognitive paradox and rational basis behind the "irrational behaviors" generally considered to be "irrational behavior" by some historical figures in their later years, such as various superstitions, dogmatism, stupor, and murder.

Therefore, the definition of the term "superstition" with rational basis in this paper refers to the phenomenon that people turn to increase their confidence in the existence of supernatural forces after observing the occurrence of a very small probability event (that is, P (God) |"miracle") this posterior probability increases), and accordingly influences its subsequent behavioral patterns.

I like history. The so-called "no beginning, no end", history has never been short of big figures who are not guaranteed at the end of the season. Sweeping Liuhe is like the first emperor, and he is in Penglai Xiandao; chasing the Xiongnu in the north is like Han Wu, and he is burdened by alchemists in his later years; being good is like Tang Zong, and it is inevitable to eat the elixir and die. I can't help but sigh. The big-eyed Li Shimin actually rebelled against the revolution.

All of the above are classified as mediocrity in old age, or as limitations of the times. I have a vague feeling that this explanation is inappropriate: Personality worship, begging immortals to visit Dao is almost a common problem of emperors of all dynasties, are they all dizzy? Even today, there are many statues of gods praying for blessings in the homes of high-ranking officials who are known as atheists. This is not a limitation of the times, right? Whether trapped in longevity or fascinated by illusions, it is undeniable that Qin Huang, Han Wu and even today's high-ranking officials have far more insight and knowledge than Zhu Ji. There is always something understandable in everything, not to mention these first-class people, who are generally considered "stupid", not as an explanation, but as an excuse to avoid understanding. So I tried to use probability to explain some of their behaviors, and found that there is a solid logical basis behind the "superstition".

1. The Bayesian Model of Miracles

What is the probability? Let’s look at a simple example: given that there are ten socks in a drawer, three of which are red and seven are blue, the probability of randomly picking red socks is 3/10. This is the classical probability defined by frequency, characterized by the fact that the total number of socks is determined and known. When we say that the probability is 3/10, of course, it does not mean that 3/10 red socks can be drawn each time, but that when the number of draws is large enough, such as 10,000 draws, there are roughly 3,000 red socks. An important and often overlooked point here is that we can naturally imagine ourselves drawing 10,000 results, which fits very well with life experience. However, life experience doesn't help with some problems.

Like winning the lottery. The lottery is known to have negative expectations, and most mathematically literate people shy away from the lottery because they believe winning or not is completely random. There's an accepted premise here: There's no god in this world to help you win the lottery. I think so too. Does this seem like nonsense? No, going back to the example at the beginning of the article, people are always making some kind of probabilistic judgment. Rather than saying that I don't believe that God helped me win the lottery, I believe that the probability of "God made me win the lottery" is far less than 1/2.

However, suppose one day on the road I meet a rambling old man who insists on dragging me to buy a lottery ticket. Three days later, he actually won the $40 million Powerball! At that time, even though I graduated from the Department of Mathematics, I had to give up the prejudice of "god nagging" before, and worshipped the old man like a god. Even when I couldn't sleep at night, I recalled whether I had done good deeds recently and received good rewards. . Such a result is comical, as if I had given up my rational stance under the temptation of a lot of money and devoted myself to the cause of superstition. In fact, it is not. What I want to point out is: I adhere to the principle of rationality from beginning to end, and rationality and "superstition" are not contradictory.

Specifically, let's say the probability of winning the Powerball in the United States is y, and the probability that I think the old man is a god is x.

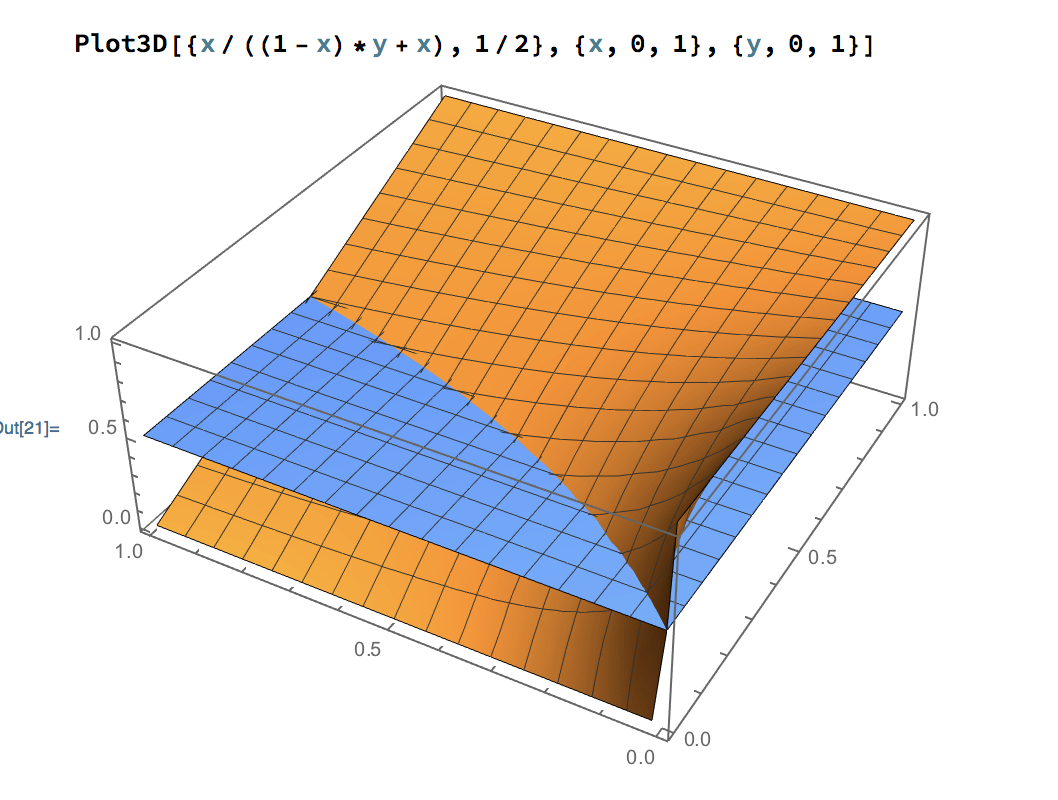

That is, P(God)=x, P(Winning|No God)=y,

Then P(winner|God)=1, P(winner)=(1-x)*y+x*1,

Therefore P(God|Winning)=P(God)*P(Winning|God)/P(Winning)=x/(y-xy+x)

The last thing mentioned above, for an observer with a belief probability of "the existence of God" of x, if he encounters an event with a random probability of y, he will correct his belief in God because of the observation of a small probability event at this time. The confidence probability of is x/(y-xy+x).

But this expression has two variables, x and y, which is still not intuitive enough. What we need to consider is that what kind of person encounters what kind of small probability event will significantly affect his probability estimation of supernatural existence, so we might as well set n=x/y (n is obviously non-negative), and bring it into the above formula to get:

P(God|Winning)=n/(1+n-ny)>n/(1+n), the right side of the inequality is an increasing function of n, approaching 1

When n=1, P(God|Winning)>1/2; When n=2, P(God|Winning)>2/3;...As n tends to infinity, P(God|Winning) tends to 1

That is to say, if the observer previously estimated the probability of the existence of God as x, then no matter how small x is, as long as he encounters an event with a random probability smaller than x, then from a rational point of view, the conditional probability of the existence of God in his mind will soar to greater than 50%; if the random probability of the event is only half of x, the probability of the existence of God in the observer's mind will rise to greater than 66%; if the random probability of the event is only one percent of x, then the observer The probability of the existence of God in the heart will be greater than 99%.

2. People's cognitive dilemma for extremely unlikely events

Some people may say, I don’t believe in God at all, and my x is strictly equal to 0;

First of all, it must be pointed out that what is discussed here is not the "objective probability" of the existence of God, because when it comes to supernatural God, it is impossible to define probability in terms of frequency. The probability discussed here is more like a "feeling" of people. Shanghai dialect is a gross estimate. Although no normal person would think about estimating the probability of God's existence, when a crisis comes, everyone has already estimated the probability subconsciously.

Next, respond to the group of people with x=0. In the United States, statisticians and physicists have modeled and claimed that the odds of hitting a powerball (1 in 290 million) are lower than falling from the top of the World Trade Center and not dying. Everyone is shouting nonsense, what are you kidding if you fall from the World Trade Center without dying, this is obviously a zero probability event; but someone will definitely hit the Powerball. The professor's model may be too ideal, but people's reasoning chain is undoubtedly wrong-because no one has ever seen a scene where nearly 200 million people lined up to jump off a building, and can't even imagine it (otherwise, it would not assert 0 probability) . This once again exposes the powerlessness of human beings to the problem of extremely small probability. At the sensory level, we cannot measure the weight of two extremely small probability events at all, but the lottery ticket will inevitably show the lucky one due to the special mechanism, and it seems that people are at a loss. life-saver. Everyone knows that judging the probability of "I have never seen it" vs "At least one winning lottery" is actually as simple as the folk statistics of "winning the lottery is 100%, it must not be 0%".

Here is a necessary lemma: Humans are limited in their visualization of numbers, so that they cannot accurately perceive very large numbers and very small probabilities.

For example, Li Ziran once said that there was a high-voted answer on Tucao Zhihu. In order to point out the deceptiveness of the average, the answer said, "Ma Yun, Wang Jianlin, and Ma Huateng add up to billions, but it's useless. Everyone understands the truth, but it sounds particularly harsh - "You, Jack Ma, Wang Jianlin, and Ma Huateng add up to billions... Who are you insulting? These people add up to at least 500 billion." Gao Zan is a medical doctor The editor of No., for him, billions are already the upper limit of what he can perceive. For him, there is no obvious difference in perception between tens of billions and 100 billions from one billion (of course you can say "" "10 billion scalpels" and "100 billion scalpels", but you can't separate the two into distinct blocks in your mind, you can imagine a thousand scalpels.) However, it is conceivable that the financial industry is much more sensitive to large numbers. Ten billion, one hundred billion, and one trillion are distinct concepts for them, because they can at least correspond to companies of different sizes. It can be seen that although everyone knows numbers, if we really want to "conceptualize" a quantity into a specific and perceptible concept, then everyone's upper and lower limits of perception are different, just like different rulers have different minimum and minimum values. scale.

In the same way, a very small probability is the reciprocal of a very large number, and it is naturally difficult for humans to perceive it accurately. For example, when it comes to Banhua Bancao, most people will have a clear imagination, which shows that we have a feeling about the probability of about 1/20. As for school flowers and school grass, there should also be a shadowy impression, but except for a few old drivers, most people are afraid that they can't tell the specific difference between the standards of school flowers and class flowers, which means that we have a probability of 1/20 and 1/200. The distinction has been blurred. As for the university flower and the school flower, it is even more disagreeable. Beiying and Nortel can buy 5 school flower hot searches in three days, which shows that the public's conceptualization of the probability of the order of 1/200 to 1/2000 is already a mess. . Don't say "one in a thousand miles, one in ten thousand miles", can you really tell the difference between one in a hundred and one in ten thousand?

The above only talked about people's unavoidable cognitive lower bound for the conceptualization of small probability, that is, for any small probability event whose random probability is less than the lower bound, people's perception of it can only be the same as the perception of the lower bound. (It may be added here that I do not deny that everyone knows that the probability of picking a random person from the world (1 in 7 billion) is about twice the probability of picking a random woman; I mean, if If you ask these two extremely unlikely questions independently, then his two perceptions before and after should be similar, both touching the blind spot of perception, and not having twice the psychological feeling)

Next, let's talk about people's perception of the probability x of the specific proposition "whether God exists". I think everyone's x is different, but most people's x is much larger than expected. Hume once said when expounding skepticism that unless we believe that a small probability event has a lower probability of occurrence than the probability of God's existence, we cannot regard this event as a miracle that supports the existence of God. (This is actually equivalent to an inverse proposition of my equation above, because when x=y, the conditional probability is slightly more than half, and Hume said that unless y<x, the event corresponding to y cannot be regarded as a miracle, which is an approximation. ) Here we look at Hume's proposition in reverse, that is: since so many people convert to God because of witnessing "miracles", it also means that their subconscious valuation of the existence of God is no greater than the random probability of those "miracles" .

For example, I have a friend whose grandmother, mother and he are Christians, but his father is not. Later, my father experienced a serious illness, and according to doctors, the chance of survival was less than one percent. So friends and mother prayed for it all night, and my father accepted that if he could really be healed, he must believe in Christ. In the end, his father really survived. The family believed that this was undoubtedly the power of God, and his father also believed in Christ from then on.

I don't talk about beliefs here, just look at the cold numbers. The doctor said that the chance of survival is less than 1 in 100, so we can always put the range to 1 in 10,000. This also means that the friend's father's inner valuation of "whether the Almighty Lord exists" is at least greater than one ten thousandth. And 1 in 10,000 should be the smallest random probability among all the miracle stories I have heard of converting to religion.

But even if x is reduced to x=1/10000, it is still not enough to see in front of the Powerball. Powerball winning probability y=1/290000000. Substitute into P(God|Winning)=x/(y-xy+x)=99.997%. That is to say, for a person with a 1 in 10,000 probability of believing in a god, the probability that he will start to believe in metaphysics after winning the Powerball is 99.997%.

In other words, combining the fact that the old man let you win the lottery at the beginning, changing from doubt to "believing that he is a god" is a rational choice. This almost amounts to saying that once a player has won the lottery, there is no reason to suspect that the old man is not a god.

Of course, as mentioned earlier, estimating the probability x of "the old man is a god or not" here is just a "feeling" and cannot be strictly defined. Recall the previous example of pumping socks, the classical probability is actually the ratio of the future frequency of the event to the total number. There are two premises here: events are repeatable and their results can be verified. However, neither of these two premises hold true when considering the existence of a transcendent God:

1. Events can be repeated.

Of course, people also define the probability of some seemingly unrepeatable events, such as the use of new drugs by doctors for critically ill patients, with a fatality rate of 5%. It is true that if a patient dies, the trial "death" cannot be repeated; but in this context, the patient is no different from other patients taking this drug, so the event of "patient death" can be repeated. Its probability is determined jointly by all clinical cases. So the question is, how to apply the probability of this frequency definition to the proposition "Is the old man a god"? If I say that I think the old man is a god with a probability of 1 in 10,000, that doesn't mean "After I meet 9999 more old men on the street, I'll probably have a god with him." (Then there would be dozens of gods on earth. 10,000); rather, in every possible world that I can imagine, among the 10,000 old men I meet among the 10,000 planets in this bright starry sky at this moment, there will be one real God. However, this is pointless, because whether there are parallel planes or not is completely elusive. Premise 1 does not meet.

2. The outcome of the event is verifiable

Doctors come to the fatality rate because patients have only two easily observable vital signs: life and death. However, for "God", there are no definite signs to observe. If someone can bet right in every game of every World Cup from birth, then people are naturally regarded as the god of gamblers. But this is not because he has shown some objective divine power (objectively, of course, it is possible to guess any game right by pure luck), but it is just that the probability that he is a god in everyone's heart is a little higher than the probability of guessing right in every game , although this This "probability size" is strictly a rough estimate.

Probability is a powerful weapon for human judgment. As long as there is relevant data or similar cases, a probability with considerable credibility can be concluded. However, fate is such a completely incomprehensible and unanalyzable existence. If I say that there are only two possibilities of whether a place will have an earthquake every day or not, so each accounts for 50%, I will definitely be ridiculed by people for not understanding mathematics. Yes, earthquakes depend on a large number of observable phenomena. Based on these experiences, people can assert that the probability of an earthquake in any city is much less than 50% every day. make a distinction. But what about the mysterious and mysterious things like "God blesses" or "True Destiny"? The simple guess of 50% may seem ridiculous, but it's never more ridiculous than any number between 0 and 1. If there was a supercomputer, it would probably only be able to say, "Not enough data to model."

According to my analysis above, anyone who wins a huge lottery with a very small probability will inevitably fall into the logical dilemma of "whether there is a god to help". So why do most people disagree and think that winning the lottery is just a random event? The reason is simple, not everyone wins the jackpot. In fact, you don't need to win the lottery by yourself. Even if the old Wang next door wins 20 million in the lottery shop across the street, I think Uncle Wang's image can instantly rise up. It's normal to buy one to try your luck.

Why is it okay for other people to win the lottery, but I (or the people around me) win the lottery, so I think about ghosts and ghosts?

There is a taste of solipsism in this, that is, people tend to regard the self and the external world as two parts, and think that the self is an existence detached from the external world.

As for the lottery, the little a I don't know won the lottery. I think it was just a random selection of the number of the little a. One of millions of people will always win the lottery. There is no difference between small b, c and d in the mathematical model of lottery tickets.

So what if I win the lottery myself: "I'm no different from Zhang San and Li Si who didn't win the lottery? Haha! How is that possible! I'm a genius, right? When I saw my dentist a few days ago, the doctor said that I have the appearance of an emperor in my teeth!"

The essence of this mentality is that when people fall into the binary opposition of "I and the world", they cannot fully identify themselves with other people, and they are unwilling to accept that they are just randomly selected. To convince "I" that it's just a one-in-a-billion chance, that "I" cannot compete with hundreds of millions of other people for the grand prize (although this is true in the eyes of the beholder), the only thing that fits the "I" The logic of "whichever" is to describe it as "I" can probably only be hit once in hundreds of millions of future lives. However, although this explanation is in line with the psychology of dualism, it touches on another question that makes probability invalid: Is there an afterlife?

Do I have an afterlife? What I have experienced can no longer be repeated in this life. Is it possible that it will appear ordinary in the next life? Did I win the lottery by accident, or was it irreversibly chosen by fate?

This is why I use lottery tickets to do probability analysis, because these questions pop up in the minds of the Qin emperors and Hanwu all the time.

2. Reinterpretation of the "irrational behavior" of historical figures

When I was a child, I read Zhu Yuanzhang's biography, and there was a story that puzzled me.

It was the era of the coexistence of heroes at the end of the Yuan Dynasty. Zhu Yuanzhang attacked the powerful Chen Youliang in Poyang Lake with a fire attack, thus laying the foundation for domination of the world. Looking at it now, the Poyang Lake naval battle seems to incorporate the plot of Chibi and Guandu, which is extremely thrilling. Zhu Yuanzhang's boat was attacked by heavy artillery from General Chen Youliang Zhang Dingbian. At the critical moment, Liu Bowen was quick to pull Zhu Yuanzhang away from the boat. When Zhu Yuanzhang arrived at the new boat, the old boat sank. What puzzled me was that Liu Bowen, instead of taking credit and pride, was more loyal and regarded Zhu Yuanzhang as a divine man blessed by the mandate of heaven.

Wait a minute, didn't you just pull this god man to death without being blown up? You were the one who saved him, how could it be destiny? Is this little Zhuge completely illogical?

Later, I finally realized that it was not that Liu Bowen had no logic, but that I did not really consider the "context" of his thinking. Whether Zhu Yuanzhang was not killed by heavy artillery and even his subsequent capture of the world was a random event or fate, the difference between the two stems from the different perspectives of readers and witnesses (Liu Bowen).

Zhu Yuanzhang is insignificant to me in later generations. When he died, Chen Youliang took over the world at the most. Although Chen was later defiled by the Ming government and novels, he was much stronger in national integrity than the Ming Taizu who repeatedly surrendered Yuan; What's more, there is a Zhang Shicheng in the east who loves the people like a son - whoever takes the world is not necessarily worse than the old Zhu family who has lost countless monarchs. If Zhu Yuanzhang is equal to one of the ordinary leaders of the tens of thousands of uprisings at the end of the Yuan Dynasty, then it opens the door for probability theory - Yuan loses its deer, the world chases it, and Zhu Yuanzhang is the one who was randomly selected.

However, Liu Bowen could not think so. He is Zhu's mastermind. It can be said that every loss is a loss and a glory is a blessing. His life and wealth are all on Zhu's body. How can Zhu Yuanzhang be regarded as lightly as other rebel leaders. Before the naval battle with Chen Youliang, Zhu Yuanzhang led his troops north to rescue King Xiaoming. Liu Bowen refused, saying that Chen Youliang would come to sneak attack, and Zhu would not listen. The result was as Liu Bowen expected, Chen Youliang did attack in a big way, Zhu Yuanzhang hurried to meet the enemy, and the result... a great victory. The cannon blew up by the side...still a big win. I don't think Liu Bowen would doubt his judgment, but he just had to admit that the lord was lucky. But the luck of the king, the luck of the country, isn't luck also the embodiment of destiny?

So our wise man Liu Bowen was caught in such a dilemma: Do you think that Lao Zhu was just lucky, the cannonball was just a few inches from his feet, and I just happened to be in danger and just reached out and hooked it? Or is the destiny on Lao Zhu, he can't die at all, and I, Liu Bowen, standing beside him at that time also meant heaven? The former is obviously a very unlikely event, while the latter is a possibility with unknown probability. Which is bigger or smaller?

Liu Bowen probably didn't hesitate too long. Because he can't be like the readers, assuming that Zhu Yuanzhang was killed by Chen Youliang or Zhang Shicheng, they will also unify the world, so he came to the conclusion that "the fact that Lao Zhu was not killed reflects the randomness". This assumption can't be said to be wrong, but it doesn't make sense to Liu Bowen - whoever encounters a flight crash will tell themselves to be normal, this company crashes every few million flights, and I just happened to verify the randomness today? No, because everything is empty after death, what's the point of probability? What's more, the "self" is never willing to be reduced to the data as ordinary as the external individuals to be taken into account in probability. No matter how detached Liu Bowen was, he couldn't see Zhu Yuanzhang, who had something to do with his own life and family, be so turbulent, otherwise he would have ridden out of Hangu Pass in the west long ago.

This is my understanding of the wise Liu Bowen. What about Zhu Yuanzhang, the great ancestor? What he saw was far better than what Liu Bowen saw. Not only did he see cannonballs falling at his feet, but he also knew that he was helped when he was starving to death as a child. When he was first in the army, he always managed to save his life even if he was desperate. He had encountered many assassinations in his life. Legend has it that Liu Ji, a wise man who knows the power of ghosts and gods, also worships him like a god-how can he not believe in himself and be extraordinary? (Of course, the story of Liu Bowen's rescue of Zhu Yuanzhang is undoubtedly a novelist's words, but because Zhu Yuanzhang and other characters have undoubtedly experienced many small probability events of escaping from death, replacing Liu Bowen's story with any one will not affect the conclusion, so it is retained. this dramatic plot.)

Of course, this mental dilemma is a lot like a well-known football trick. That is, sending emails to 200,000 people to predict the results of the World Cup knockout at the same time, half of the email guesses will win, and half of them will be eliminated; then after one round, there are 100,000 emails with "accurate" answers. In the next round of knockout, 50,000 emails will be selected to win, and the remaining guesses will be eliminated, then there will be 25,000 correct emails, and so on. There are four knockout rounds starting from the top 16 in the World Cup, so there must be 6,250 emails for four consecutive times. right. These 6,250 recipients tend to be so hot-headed that they treat the scammers like gods, and eventually start spending money on the scammers' "pre-match predictions".

The victims of this deception are undoubtedly very similar to Liu Bowen and Zhu Yuanzhang. After experiencing a series of small-probability events, they turned to deny the randomness and believed in "the help of gods". However I don't think the Bowen Laus were as deceived as these victims and made stupid decisions. The reason is very simple. The principle of gambling and deception and who is responsible are obvious. Even if it is not certain whether it is a deception or not at the moment of receiving the email, the recipient at least knows that the truth is in the hands of the person who sent the email. He is either a god or a It's a liar who knows when he asks - but just like Zhu Yuanzhang, he is dying, and the fire is not on his side. Who should Liu Bowen go to and ask what is going on with this tm? No one can ask, unknowable, the probability of the ultimate question is always x.

So it can't be said that Liu Bowen is wrong. There is no right answer. What's wrong? Human knowledge cannot explain or understand the ultimate end of the world. At most, it can only be said to try to explain or try to understand - but the essence is still to calm one's own curiosity, fear, and insecurity.

The Bible records that Christ has great supernatural powers, he can walk on water, he can draw bread to save people, and he can cure measles without medicine. If this really happened in the Middle East more than 2,000 years ago, how did you make the people at that time believe that he was not the son of God? Most of the opponents think that these things do not exist, which is understandable, but in essence, they are only arguing about the authenticity of religious records - the stories of Buddha, Mohammed, and Jesus can all be fabricated, so they are not credible. . However, they avoid the really crucial question "how should people behave when a very unlikely event (almost miraculous) happens around us"?

If one day, an alien astronaut falls from the sky, he dresses himself up as a god, calls the wind and calls the rain, builds a nuclear power plant with only one hand, catches a cold to solve global warming, goes to the hospital and talks about cancer and cancer. After the medicine is cured, people will think that he is a god or an astronaut who pretends to be a god and actually has high technology? Will he be regarded as the alien Bethune, or the Pangu of the new age?

Of course, you may say that this part of me is purely boring, and I made up an event to make myself happy. Yes, this incident is purely fictional, and it is almost impossible for such miracles to happen, but it is undeniable that historical figures like Zhu Yuanzhang and Li Shimin, the legends that happened to them are no less than these miracles. . We can't feel it, but we can imagine it.

Was Zhu Yuanzhang addicted to murder? Very bloodthirsty, the Hu Weiyong case and the Lanyu case killed the founding fathers to the bare bones--is it because of his character? Not necessarily, not if you believe you are a dragon. For example, no one except Buddhists thinks killing a fly is so sinful.

To look at history in the context of history is not only to consider the background and customs of different eras, but also to consider the state of mind of historical figures at that time. Otherwise, watching all the emperors and generals is either a murderer or a paranoid, it is not interesting.

This article attempts to explain a paradox in history and even in reality (only that the probability of happening to great people in history is very high), when a small probability event occurs to a stranger, out of general logical reason, people tend to agree with it. Randomness; but when an event with a very small probability happens to oneself, due to the "dualistic" instinct to treat the self and the outside world differently, people will not consider themselves as a simple individual into the probability consideration, but expand the "logic". Domain", incorporating into the subconscious analysis the notion that God exists (to help him perform miracles), which is usually seen as a joke. Since there is no trace of the "probability" of God's existence, most people will acquiesce that this probability is greater than the random probability of an event with a very small probability that has occurred, and therefore believe the former.

Of course, this article is not to prove the existence of God (this is not a "logically well-defined" question), but to explain why the princes and generals who were previously regarded as "greedy for profit" and "specializing in monopoly", why they always Inevitably a disdainful "superstition" color. Rather than believing that these geniuses are "old and confused" at the same time, I believe that we haven't really understood the realm of their thinking. However, this article puts too much emphasis on "rationality" and "probability". Is the scale of Zhu Yuanzhang's consideration just a trade-off of probability? Are they the same as today in terms of life and death, self-worth, and self-worth? If this article is to develop and discuss the psychological structure of ancient emperors and generals, it must combine a cross-cultural perspective. Therefore, this article just supplements a perspective of reinterpreting the "superstitious activities" of historical figures, and does not intend to claim that they are completely rational, but at least reveal that there is a certain rational element behind their superstitious behavior. These ingredients can make us "intimidated" by our "difficult to communicate" superstitions. Superstitions are not monsters of delusional logic.

The dogmatism and superstition of Zhu Yuanzhang's external performance is rooted in the fact that they have experienced too many small-probability events, so that their thinking samples are different from ordinary people, and the posterior probability of "God helping me" has been greatly improved. Although the realm of God is elusive to human beings, each person’s view of God and the resulting changes are ultimately human’s own behavior, which can and should be understood. This is very important in historical research and real-life communication, and should not be simply reduced to "superstition" - it is not solving problems, just avoiding thinking.

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…